Code of Justinian

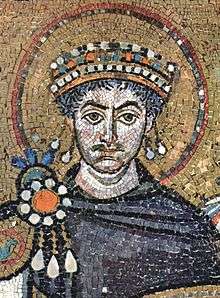

The Code of Justinian (Latin: Codex Justinianus, Justinianeus[1] or Justiniani) is one part of the Corpus Juris Civilis, the codification of Roman law ordered early in the 6th century AD by Justinian I, who was an Eastern Roman (Byzantine) emperor in Constantinople. Two other units, the Digest and the Institutes, were created during his reign. The fourth part, the Novellae Constitutiones (New Constitutions, or Novels), was compiled unofficially after his death but is now also thought of as part of the Corpus Juris Civilis.[2]

Creation

Shortly after Justinian became emperor in 527, he decided the empire's legal system needed repair. There existed three codices of imperial laws and other individual laws, many of which conflicted or were out of date. The Codex Gregorianus and the Codex Hermogenianus were unofficial compilations. (The term "Codex" refers to the physical aspect of the works, being in book form, rather than on papyrus rolls. The transition to the codex occurred around AD 300.)[3] The Codex Theodosianus was an official compilation ordered by Theodosius II.[3] In February 528, Justinian promulgated the Constitutio Hac quae necessario, by which was created a ten-man commission to review these earlier compilations as well as individual laws, eliminate everything unnecessary or obsolete, make changes as it saw fit, and create a single compilation of imperial laws in force.[4] The commission was headed by the praetorian prefect, John of Cappadocia[5] and also included Tribonian, who was later to head the other Corpus Juris Civilis projects.[6]

The commission finished its work in 14 months, and the compilation was promulgated in April 529 by the Constitutio Summa.[7] However, this compilation did not eliminate all the conflicts that had arisen over the years in Roman jurisprudence, and the constitutions in the Code were to be used alongside the conflicting opinions of ancient jurists. "The citation of the said constitutions of Our Code, with the opinions of the ancient interpreters of the law, will suffice for the disposal of all cases."[8] Justinian attempted to harmonize these conflicting opinions by issuing his "Fifty Decisions" and by passing additional new laws. This meant that his Code no longer reflected the latest imperial law. Thus, Justinian ordered a new compilation to supersede the first, and this Codex was published in 534.[9] No copies of the first edition of the Code have survived; only a fragment of an index of contents on an Egyptian papyrus remains.[10] Known as the Codex Repetitae Praelectionis, this second edition of the Code was published on November 16, 534, and took effect on December 30.[11] The Codex consists of twelve books: book 1 concerns ecclesiastical law, sources of law, and the duties of higher offices; books 2–8 cover private law; book 9 deals with crimes; and books 10–12 contain administrative law. The Code's structure is based on ancient classifications set out in the edictum perpetuum (perpetual edict), as is that of the Digest.

Rediscovery

In the West, Justinian's Codex was largely lost, or in many places never present, due to the limited western extent of the Byzantine territories. The Latin version known today was painstakingly restored over many centuries. The only known manuscript that once contained the entire Latin Codex is a Veronese palimpsest of the 6th or 7th century; it is now only fragments.[12][13] Within its home in the Byzantine Empire, the code was translated into Greek, which had become the governing language, and adapted, in the 9th century as the Basilika. It appears as if the Latin Code was shortened in the Middle Ages into an "Epitome Codex", with inscriptions being dropped and numerous other changes made.[14] Some time in the 8th or 9th century, the last three books of the Code were separated from the others, and many other laws in the first nine books, including all of those written in Greek, were dropped.[15] Substantially complete versions of Justinian's Codex were restored around the end of the 12th century, and the humanists of the 16th century added the laws originally promulgated in Greek.[16] Paul Krüger created the modern, standard version of the Codex in 1877.[17]

English translations

No English translations were made of the Codex until the 20th century. In 1932, the English translation of the entire Corpus Juris Civilis (CJC) by Samuel Parsons Scott was published posthumously.[18] Unfortunately, Scott used the Kriegel brothers' edition of the CJC rather than that of Theodor Mommsen, Paul Krüger, Rudolf Schöll and Wilhelm Kroll, which is accepted as the most reliable, and his translation was severely criticized.[19][20][21] Reviewing Scott's work, the Roman law scholar W. W. Buckland wrote that Scott "...had at his disposal an adequate latinity and has produced a version written in an English which can be read with pleasure. But much more than that was needed, and the work cannot be said to satisfy these further requirements."[22] Around the same time that Scott was active, Wyoming Supreme Court Justice Fred H. Blume was translating the Code and Novels, using the standard Mommsen, Krüger, Schöll, and Kroll version.[23] While this was not printed in his lifetime, in 2005 his translation of both the Code and the Novels was published on the Annotated Justinian Code website.[24] A new English translation of the Codex, based on Blume's, was published in October 2016.[25]

Codex Repetitae Praelectionis

The Codex Repetitae Praelectionis was the second edition of the Code of Justinian. It came into force by the constitution Cordi on 16 November 534 and was necessary due to Justinian's own legislative activity in creating new laws since the original code was issued in 529. It consists of 12 books and was written mainly in Latin.[26]

References

- Chambers's Encyclopaedia: A Dictionary of Universal Knowledge. p. 324.

- See generally, Honoré, 2003

- Jolowicz, 1972, p. 463

- Jolowicz, 1972, p. 479.

- Caroline Humfress, "Law and Legal Practice in the Age of Justinian," in The Age of Justinian 161, 163 (Michael Maas ed. 2005). Humfress also describes the diverse forms of imperial enactments that were included.

- Honoré, 2003, supra note 1

- Honoré, 2003, supra note 1 at 803

- Humfress, supra note 5 at 165, quoting the Constitutio Summa.

- Honoré, supra note 1 at 804. For an English translation of the law putting this second edition into force, see "Concerning the Correction of the Justinian Code, and the Second Edition Thereof" (November 16, 534), translated by Justice Fred Blume in the Annotated Justinian Code at page 4.

- Wolfgang Kunkel, An Introduction to Roman Legal and Constitutional History 166 (J.M. Kelly trans. 2nd ed. 1973).

- Jolowicz, 1972, supra note 2 at 494.

- Jolowicz, 1972, supra note 2 at 495

- Stephen L. Sass, Research in Roman Law; a Guide to the Sources and Their English Translations, 56 Law Library Journal 210, 225 (1963).

- Charles M. Radding & Antonio Ciaralli, The Corpus Iuris Civilis in the Middle Ages: Manuscripts and Transmissions from the Sixth Century to the Juristic Revival 133 (2007); pages 133-168 give a detailed account of the Code's transmission in this period.

- A. Arthur Schiller, Roman law, Mechanisms of Development 37 (1978).

- Jolowicz, 1972, supra note 2 at 496.

- Krueger, Paul (1877), Codex iustinianus (in German).

- The Civil Law including the Twelve Tables, the Institutes of Gaius, the Rules of Ulpian, the Enactments of Justinian, and the Constitutions of Leo..., 17 vols. (1932). Reprinted in 1973 by the AMS Press.

- Timothy Kearley, "Justice Fred Blume and the Translation of Justinian's Code".

- Each of the units of Mommsen, Krüger, Schoell and Kroll CJC Archived 2013-04-06 at the Wayback Machine.

- Miller and Kearley (2013) A selective English translation of Kroll's Preface to Novels.

- W.W. Buckland, "Book Review," 7 Tulane Law Review 627, 629 (1932–33).

- See Kearley, supra note 18.

- "Blume and Justinian". Uwyo.edu. Retrieved October 26, 2016. For further discussion of the work of Scott, Blume, and Clyde Pharr on Roman law translation see Kearley, Timothy G., "From Rome to the Restatement: S.P. Scott, Fred Blume, Clyde Pharr, and Roman Law in Early Twentieth-Century". See also Timothy G. Kearley, Lost in Translations: Roman Law Scholarship and Translation in Early Twentieth-Century America 162–164 (2018).

- Bruce W. Frier (General Editor), Serena Connolly, Simon Corcoran, Michael Crawford, John Noël Dillon, Dennis P. Kehoe, Noel Lenski, Thomas A.J. McGinn, Charles F. Pazdernik, and Benet Salway, with contributions by T. Kearley. (2016), The Codex of Justinian. A New Annotated Translation, with Parallel Latin and Greek Text (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016), p. 2963, ISBN 9780521196826

- "Codex Justinianus" in The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium, Oxford University Press, New York & Oxford, 1991, p. 474. ISBN 0195046528

Sources

- Tony Honoré, Oxford Classical Dictionary. Edited by Simon Hornblower and Antony Spawforth. 3rd rev. ed. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2003. ISBN 978-0-19-860641-3.

- Jolowicz, H. F.; Nicholas, Barry (October 26, 1972), A Historical Introduction to the Study of Roman Law, CUP Archive, p. 463, ISBN 978-0-521-08253-2.

External links

- Information on the Justinian Code and its manuscript tradition on the Bibliotheca legum regni Francorum manuscripta website, A database on Carolingian secular law texts (Karl Ubl, Cologne University, Germany).