Temple of Jupiter (Roman Heliopolis)

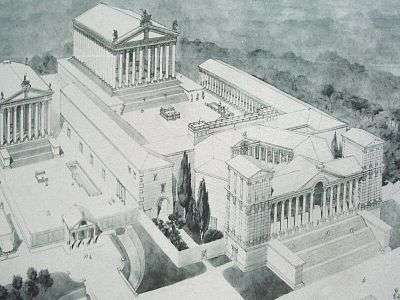

The Temple of Jupiter is a colossal Roman temple, the largest of the Roman world, situated at the Baalbek complex in Heliopolis Syriaca (modern Lebanon). The temple served as an oracle and was dedicated to Jupiter Heliopolitanus.

It is not known who commissioned or designed the temple, nor exactly when it was constructed. Work probably began around 16 BC and was nearly complete by about AD 60. It is situated at the western end of the Great Court of Roman Heliopolis, on a broad platform of stone raised another 7 m (23 ft) above the huge stones of the foundation, three of which are among the heaviest blocks ever used in a construction. Cultic activity had long taken place at the site; the temple presumably replaced an earlier one, possibly using the same foundation.[lower-alpha 1]

It was the biggest temple dedicated to Jupiter in all the Roman empire. The columns were 30 meters high with a diameter of nearly 2.5 meters: the biggest in the classical world. It took three centuries to create this colossal temple complex.

History

The huge quarry nearby likely played into the Roman decision to create a huge "Great Court" of a big pagan temple complex in this mountain site, despite being located at 1100 meters of altitude and lying on the remote eastern border of the Roman Empire.

Although the 6th-century Greek historian John Malalas dates the temple to the reign of Antoninus Pius (AD 138–161), construction probably started soon after c. 16 BC, when Baalbek became a Roman colony known as Colonia Julia Augusta Felix Heliopolitana. It was largely completed by AD 60 as evidenced by a graffito located on one of the topmost column drums.[3][4][5] It was an important religious site during the Roman empire, and emperors often consulted the temple's oracle. Trajan learned of his imminent death c. AD 115.[3]

The temple complex is on a raised plaza erected 7 m (23 ft) over an earlier T-shaped base consisting of a podium, staircase, and foundation walls.[lower-alpha 2] These walls were built from about 24 monoliths, at their lowest level weighing approximately 300 tonnes each. The tallest retaining wall, on the west, has a second course of monoliths containing the famed "Three Stones" (Greek: Τρίλιθον, Trílithon):[6]: cut from limestone, measuring over 19 m (62 ft) long, 4.3 m (14 ft) high, and 3.6 m (12 ft) broad, they weigh approximately 800 tonnes each.[7] (A fourth, still larger stone called the Stone of the Pregnant Woman lies unused in the nearby quarry 800 m (2,600 ft) from the town[8] and weighs around 1000 tonnes.[9] A fifth, weighing approximately 1200 tonnes[10] lies in the same quarry.) Through the foundation there run three enormous passages the size of railway tunnels.[6]

A wide staircase provided access to the elevated platform, which measured 47.7 m × 87.75 m (156.5 ft × 287.9 ft) on top.[11] The Temple of Jupiter proper was circled by a peristyle of 54 unfluted Corinthian columns:[12] ten in front and back and nineteen along each side.[11] The columns were 19.9 meters high, the tallest of any classical temple, and the apex of the pediment is estimated to have been 44 meters above the floor of the court. With a rectangular footprint of 88x44 meters, it is considerably smaller than earlier Greek temples, such as the Temple of Artemis at Ephesos and the Temple of Apollo at Didyma. Rather its significance lies in the sophistication of its planning and architectural detail.[3]

A number of Julio-Claudian emperors enriched the temple's sanctuary in turn. In the mid-1st century, Nero built the tower-altar opposite the temple. In the early 2nd century, Trajan added the temple's forecourt, with porticos of pink granite shipped from Aswan at the southern end of Egypt.

The Temple-Sanctuary of Heliopolitan Zeus was ruined by earthquakes,[13] destroyed and pillaged for stone under Theodosius[14] and again under Justinian: eight columns were taken to Constantinople (Istanbul) for incorporation into the Hagia Sophia. Three columns fell during the late 18th century.[15]

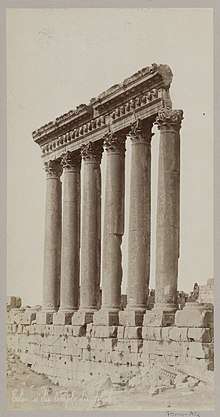

Present condition

At present, six columns remain standing along its south side with their entablature.[11] Their capitals remain nearly perfect on the south side, while the Beqaa's winter winds have worn the northern faces almost bare.[16] The remaining architrave and frieze blocks weigh as much as 60 tonnes (66 tons), with one corner block weighting over 100 tonnes (110 tons), all of them raised to a height of 19 m (62.3 ft) above the ground.[17]

Construction

The original method of construction remains an archeological mystery.[18]

This quarry was slightly higher than the temple complex,[19][20] so no lifting was required to move the stones.

Individual Roman cranes were not capable of lifting stones in the 60 to 100 tonne range. The large stones may have simply been rolled into position along temporary earthen banks from the quarry[16] or multiple cranes may have been used in combination, or they might have alternated sides a little at a time, filling in supports underneath each time.

Continued archeological investigations have been hindered by civil unrest in the region.[18]

Function

Macrobius, writing c. 400, says that the temple held a golden statue of Apollo or Zeus. Represented as a beardless youth and in the garb of a charioteer, his right hand held a whip, the left a lightning bolt and ears of corn.

See also

- Roman Phoenicia

- Temple of Bacchus

Notes

- Daniel Lohmann wrote that, "due to the lack of remains of temple architecture, it can be assumed that the temple this terrace was built for was never completed or entirely destroyed before any new construction started..."[1] "The unfinished pre-Roman sanctuary construction was incorporated into a master plan of monumentalisation. Apparently challenged by the already huge pre-Roman construction, the early imperial Jupiter sanctuary shows both an architectural "imperial" design and construction technique in the first half of the first century AD."[2]

- "Current survey and interpretation, show that a pre-Roman floor level about 5 m lower than the late Great Roman Courtyard floor existed underneath".[2]

Footnotes

- Lohmann (2010).

- Lohmann (2010), p. 29.

- Lyttelton 1996.

- Rowland (1956).

- Kropp & al. (2011).

- Jessup (1881), p. 456.

- Adam (1977), p. 52.

- Alouf (1944), p. 139.

- Ruprechtsberger (1999), p. 15.

- Ruprechtsberger (1999), p. 17.

- Cook (1914), p. 560.

- Jessup (1881), p. 460.

- Cook (1914), p. 556.

- Cook (1914), p. 555.

- EB (1878), p. 177.

- Jessup (1881), p. 462.

- Coulton (1974), p. 16.

- Batuman, Elif (18 December 2014). "The Myth of the Megalith". newyorker.com. The New Yorker. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

Nobody seems to know on whose orders it was cut, or why, or how it came to be abandoned.

- Adam & al. (1999), p. 35.

- Hastings (1898), p. 892.

Bibliography

- Cook, Arthur Bernard (1914), Zeus: A Study in Ancient Religion, Vol. I: Zeus God of the Bright Sky, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Coulton, J.J. (1974), "Lifting in Early Greek Architecture", Journal of Hellenic Studies, Vol. 94.

- Jessup, Samuel (1881), "Ba'albek", Picturesque Palestine, Sinai, and Egypt, Div. II, New York: D. Appleton & Co., illustrated by Henry Fenn & J.D. Woodward, pp. 453–476.

- Kropp, Andreas; Lohmann, Daniel (April 2011), "'Master, look at the size of those stones! Look at the size of those buildings!' Analogies in Construction Techniques Between the Temples at Heliopolis (Baalbek) and Jerusalem", Levant, pp. 38–50, retrieved 13 March 2013.

- Lohmann, Daniel (2010), "Giant Strides towards Monumentality: The architecture of the Jupiter Sanctuary in Baalbek/Heliopolis", Bolletino di Archaologia [Bulletin of Archaeology], Special Volume, pp. 29–30

- Lyttelton, Margaret (1996). "Baalbek", vol. 3, pp. 1–3, in The Dictionary of Art, 34 volumes, edited by Jane Turner. New York: Grove. ISBN 9781884446009.

- Rowland, Benjamin Jr. (1956), "The Vine-Scroll in Gandhāra", Artibus Asiae, Vol. 19, No. 3/4, pp. 353–361