Temple of Bacchus

The Temple of Bacchus is part of the Baalbek temple complex located in the broad Al-biqā (Bekaa Valley), Lebanon.[1] The temple complex is considered an outstanding archaeological and artistic site of Imperial Roman Architecture and was inscribed as an UNESCO World Heritage site in 1984.[1] The Temple of Bacchus is one of the best preserved and grandest Roman temple ruins; its age is unknown, but its fine ornamentation can be dated to the second century CE.

| Temple of Bacchus | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| |

| General information | |

| Type | Roman temple |

| Architectural style | Classical |

| Location | Baalbek, Lebanon Heliopolis, Roman Phoenicia |

| Completed | late 2nd or early 3rd century |

| Height | 31 m (102 ft) |

| Technical details | |

| Size | 66 by 35 m (217 by 115 ft) |

| Design and construction | |

| Main contractor | Commissioned by Antoninus Pius |

History

The temple was probably commissioned by Roman Emperor Antoninus Pius (r. AD 138-161). No information was recorded about the site until a 4th-century Greek conquest, by which point the temple would likely have been closed due to the persecution of pagans in the late Roman Empire. When the complex fell into disrepair, the Temple of Bacchus was possibly protected by the rubble of the rest of the site's ruins.

It was not until 1898-1903 that a German Expedition excavated two of the large temples and began reconstructions on the site.[2] In 1920 The State of Greater Lebanon was proclaimed and protections and repairs of the site were mandated by the Lebanese government.

In the mid-1970s the Lebanese civil war broke out and protections of the site ceased as Al-Biqā became a stronghold for Palestinian, Hezbollah and Syrian forces. [3] In 1984 the ruins at Baalbek were inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage site.[1] Preservation of the site began in the 1990s following the end of the war.

The German Archaeological Institute's Orient Department has done a number of archaeological excavations and research on The Temple of Bacchus and the entire temple complex.[4] The site is continually being researched and assessed, such as documentation of reliefs and sculptures, archaeozoological research on fauna in the ruins, urban development and its relationship to Baalbek. All current research on Bacchus and Baalbek from the Orient Department of The German Archaeological Institute can be found on their website.

Architecture

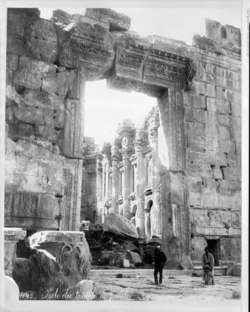

The temple is 66 m long, 35 m wide and 31 m high, making it only slightly smaller than the Temple of Jupiter.[5] The podium on which the temple sits is on an East-West axis. The peripheral wall is adorned by a colonnade of forty-two unfluted Corinthian columns with Ionic bases, nineteen of which remain upright. There are eight columns along each end and fifteen along each side —nearly 20 m (66 ft) in height. These were probably erected in a rough state and then rounded, polished, and decorated in position. The columns support a richly carved entablature, which includes an architrave with a three-banded frieze that is decorated with alternating bulls and lions and cornice ornamented with geometric and floral patterns.

Inside, the cella is decorated with Corinthian pilasters flanking two levels of niches on each side. The parapets are decorated with dancing Maenads, supporting the attribution of the temple to Bacchus. The interior of the temple is divided into a 98 ft (30 m) nave and a 36 ft (11 m) adytum or sanctuary [6] on a platform raised 5 ft (2 m) above it and fronted by 13 steps.

The entrance was preserved as late as the 16th century, but the keystone of the lintel had slid 2 ft (1 m) following the 1759 earthquakes; a column of rough masonry was erected in the 1860s or '70s to support it. The earthquakes also damaged the area around the soffit's famed inscription of an eagle,[7] which was entirely covered by the keystone's supporting column.[7] Some historic Roman coins depict the structure of this temple along with Temple of Jupiter.[8]

The Temple is enriched by some of the most refined reliefs and sculpture to survive from antiquity.[9] There are four sculptures carved within the peristyle that are believed to be depictions of Acarina which would make them the first recognizable representations of mites in architecture.[10]

Notes

- UNESCO World Heritage Site

- Seyrig, Henri (1929). "La Triade héliopolitaine et les temples de Baalbek". Syria. 10 (4): 314–356. doi:10.3406/syria.1929.3414. ISSN 0039-7946. JSTOR 4236962.

- Britannica Baalbeck

- German Archaeological Institute

- Sear (1982), p. 247.

- Jessup (1881) p. 458

- EB (1878), p. 178.

- Kevin Butcher, p 366

- Jessup (1881) p. 459 459

- Gorirossi-Bourdeau, F. (1995). "A documentation in stone of Acarina in the Roman Temple of Bacchus in Baalbek, Lebanon, about 150 AD". Bull Ann Soc Ent Belgique.

Bibliography

- Butcher, Kevin (2003). Roman Syria and the Near East. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum. ISBN 9780892367153. Retrieved 12 November 2014.

- Gorirossi-Bourdeau, F. (1995). "A documentation in stone of Acarina in the Roman Temple of Bacchus in Baalbek, Lebanon, about 150 AD". Bull Ann Soc Ent Belgique.

- Jessup, Samuel. Ba'albek (Picturesque Palestine, Sinai and Egypt) Ed. Appleton & Co. New York, 1881 ()

- Lewis, Norman N. (1999). "Baalbek Before and After the Earthquake of 1759: The Drawings of James Bruce". Levant. 31 (1): 241–253. doi:10.1179/lev.1999.31.1.241.

- Quintero, Mario; Seif, Assaad (2011). A Proposal for an Integrated risk preparedness strategy. Lebanon: Directorate General of Antiquities. ISBN 978-90-8169-530-5. Retrieved 14 November 2018. at "A Proposal for an Integrated Risk Preparedness Strategy."

- Sabel, Pennie (2002). "Baalbek Keeps its Secrets". Stone World. 19 (9): 156–162. ProQuest 213631469.

- Sear, Frank (1982). Roman Architecture. UK: B T Batsford Ltd, UK. ISBN 9781134635788. Retrieved 12 November 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Segal, Arthur (2000). "Colossal Engimas". Archaeology Odyssey: 50–53, 56, 58, 60–61.

- Wood Foreign Correspondent, Josh (August 18, 2015). "Music returns to Baalbek ruins, defying Lebanon's security concerns". National. Retrieved 16 November 2018.

- "Lebanon: Baalbek Festival". The Globe and Mail (1936-Current). May 7, 1997. ProQuest 1400733423.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Temple of Bacchus in Baalbek. |