Battle of Linz-Urfahr

The Battle of Linz-Urfahr[1] on 17 May 1809 saw soldiers from the Austrian Empire fighting against troops from two of Emperor Napoleon's allies, the Kingdom of Württemberg and the Kingdom of Saxony. An Austrian corps led by Feldzeugmeister Johann Kollowrat attacked General of Division Dominique Vandamme's Württembergers who held a fortified bridgehead on the north bank of the Danube opposite the city of Linz. As the combat got underway, Saxons led by Marshal Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte began reinforcing the defenders. This prompted Kollowrat to order a retreat, which was followed up by Napoleon's German allies.

| Battle of Linz-Urfahr | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of the Fifth Coalition | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 10,000–18,000 | 15,000–20,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 391 | 883, 4 guns–891, 6 guns | ||||||

The Austrian commander-in-chief, Generalissimo Archduke Charles, Duke of Teschen detached Kollowrat's III Armeekorps from the main army to guard Bohemia. Later, Charles directed his subordinate to threaten Napoleon's long and vulnerable supply line which followed the Danube valley. Accordingly, Kollowrat descended upon the Linz bridgehead, but the presence of a strong defending force thwarted his plans. The action was fought during the War of the Fifth Coalition, part of the Napoleonic Wars. Urfahr is part of the modern city of Linz, on the north bank of the Danube.

Background

After his defeat at the Battle of Eckmühl on 21 and 22 April 1809, Archduke Charles withdrew to the north bank of the Danube with 92,000 troops. Of these, the I Armeekorps numbered 28,000, the II counted 20,000, the III had 13,000, the IV included 15,000, the I Reserve mustered 12,000, and General-major Josef Mayer's V Armeekorps brigade had 4,000.[2] Charles regrouped his army at Cham, which is just west of the Bohemian frontier. Convinced that his army was demoralized by its defeat, Charles gave up any thought of counterattacking Napoleon. Instead, he intended to retreat from Cham to Vienna via České Budějovice (Budweis). For his part, Napoleon made up his mind to plunge forward on the south bank toward Austria's capital, Vienna. Consequently, the French emperor called off the brief pursuit by Marshal Louis-Nicolas Davout's III Corps and allowed Charles an untroubled retreat.[3]

At the outbreak of the war, Napoleon ordered Bernadotte to march the Saxon army, known as the IX Corps, to the Danube at Regensburg (Ratisbon). Because this left the Kingdom of Saxony unprotected, Bernadotte evacuated the Saxon royal family and the military stores from Saxony's capital Dresden. By 20 April the Saxon troops were at Gera on the way south.[4] Jérôme Bonaparte was ordered to march his Kingdom of Westphalia army, named the X Corps, to hold Saxony.[5]

With the Saxon army at large, Archduke Charles worried that Bohemia might be overrun and decided to leave one army corps to defend the province. For this task, he chose the III Armeekorps with its 23 battalions and 15 squadrons. To this were added 23 badly-organized battalions of Bohemian landwehr. Kollowrat was appointed to lead the III Armeekorps, while Prince Friedrich Franz Xaver of Hohenzollern-Hechingen exchanged his old corps for Kollowrat's former II Armeekorps.[6]

On the south bank of the Danube, Napoleon's forces relentlessly pressed back the outnumbered Austrian left wing of Feldmarschall-Leutnant Johann von Hiller, which consisted of the V, VI, and II Reserve Armeekorps.[7] After brutal fighting at the Battle of Ebelsberg on 3 May,[8] the Franco-Allied army appeared before Vienna. After a perfunctory resistance, Archduke Maximilian of Austria–Este abandoned the Austrian capital which was handed over to the French early on 13 May.[9]

On 4 May, Vandamme and his VIII Corps reached Linz. He found General-major Joseph von Richter and an Austrian landwehr brigade opposite Linz on the Danube's north bank. Earlier in the campaign, this unit had assisted in the blockade of the Bavarian garrison of Passau. After Passau was relieved, Richter fell back on the north bank to Linz. Aggressively, Vandamme lined up his artillery on the south bank and began to bombard Richter's men. Under cover of the cannonading, the Württembergers crossed over in boats and attacked. Richter's poorly trained landwehr were overrun and most were captured.[10]

On the 6th, Bernadotte's Saxons reached Rötz near Cham in their march around the west side of Bohemia. Napoleon wanted the IX Corps to be at Passau on the 9th, with the possibility of being ordered from there to Linz.[10] On 7 May, Archduke Charles left Budweis with his main army. He ordered Kollowrat to move from Plzeň (Pilsen) and guard his southern flank.[11] On the 8th, the Austrian army commander ordered Kollowrat to menace the French supply line near Linz.[12] Charles reunited with Hiller's wing on the north bank of the Danube on 16 May.[13]

Battle

Allied forces

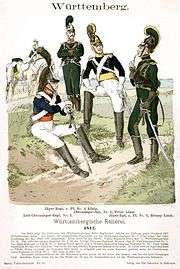

Marshal Bernadotte was in overall command of the forces of Napoleon's German allies. The 12,000-strong VIII Corps was composed of Württemberg troops and commanded by Vandamme. The corps was made up of one infantry division under General-Leutnant von Neubronn and one cavalry division led by General-Leutnant von Wöllworth.[14][15]

General-major von Franquemont's 1st Infantry Brigade included two battalions each of the Crown Prince and Duke Wilhelm Line Infantry Regiments and the 1st Battalion of the Neubronn Fusilier Regiment. The 2nd Infantry Brigade of General-major von Scharffenstein had two battalions each of the Phull and Cammerer Line Infantry Regiments and the 2nd Battalion of the Neubronn Fusiliers. General-major von Hügel's 3rd Brigade comprised the 1st König Jäger Battalion, 2nd Neuffer Jäger Battalion, 1st Wolff Light Battalion, and 2nd Brüselle Light Battalion.[14][15]

The 1st Cavalry Brigade of General-major von Röder included four squadrons each of the Leib and Duke Heinrich Chevau-léger Regiments. General-major von Stettner's 2nd Cavalry Brigade was made up four squadrons each of the König and Duke Louis Jäger zu Pferde Regiments.[14] Oberst (Colonel) von Schnadow's corps artillery had 22 guns in three companies. The 1st Foot Company consisted of eight 6-pound cannons and two 7-inch howitzers. The 1st and 2nd Horse Companies each had four 6-pound cannons and two 7-inch howitzers.[15]

Of the Saxon IX Corps, only the 1st Division of General-Leutnant von Zeschwitz was engaged in the battle. General-major von Hartitsch's 1st Brigade included the Leib Grenadier Guard Battalion, Bose Grenadier Battalion, two battalions of the König Line Infantry Regiment, the 1st Battalion of the Dyherrn Line Infantry Regiment, and the Metzsch Light Infantry Battalion. The 2nd Brigade of General-major von Boxberg was made up of two battalions each of the Prince Maximilien, Prince Frederick August, and Prince Anton Line Infantry Regiments. General-major von Gutschmid's Cavalry Brigade consisted of one squadron of the Prince Albert Chevau-léger Regiment, three squadrons of the Hussar Regiment, four squadrons of the Prince Clement Chevau-léger Regiment, and two squadrons each of the Garde du Corps and Carabinier Regiments.[16] Of these units, the Metzsch, Prince Anton, Prince Clement, Garde du Corps, and Carabiniers were not engaged. Also arriving too late[14] was the 2nd Division of General-Leutnant von Polenz.[17]

Action

Carrying out his orders of 8 May, Kollowrat concentrated the III Armeekorps at Budweis on 13 May. To guard the city of Cheb (Eger) in western Bohemia, Kollowrat detached two line (regular) and 12 landwehr battalions. Moving south, the Austrians reached Neumarkt im Mühlkreis on the 16th. Kollowrat divided the III Armeekorps into three columns for the assault on the Linz bridgehead. He ordered two columns under Feldmarschall-Leutnants Hannibal Sommariva and Josef Philipp Vukassovich to attack the bridgehead from either side. He sent Feldmarschall-Leutnant Franz Xaver Saint-Julien with the third column toward Mauthausen in a feint attack to divert attention from the main blow. Kollowrat held back a powerful reserve force.[12]

Sommariva's Right Column consisted of three battalions of the Wenzel Colloredo Infantry Regiment Nr. 56, one battalion of the Peterwardeiner Grenz Infantry Regiment Nr. 9, the 5th Jäger Battalion, three battalions of the Pilsen Landwehr, two squadrons of the Merveldt Uhlan Regiment Nr. 1, and 12 guns in two foot artillery batteries.[14]

Vukassovich commanded the Center Column. This body included three battalions each of the Manfreddini Infantry Regiment Nr. 12 and the Schröder Infantry Regiment Nr. 7, two battalions of the Wurzburg Infantry Regiment Nr. 23, one battalion of the Peterwardeiner Grenz Infantry Regiment Nr. 9, the 6th Jäger Battalion, four squadrons each of the Merveldt Uhlan Regiment Nr. 1 and the Hessen-Homburg Hussar Regiment Nr. 4, and 24 guns in four foot artillery batteries. Saint-Julien directed the Left Column. Of this force, only two squadrons of the Hessen-Homburg Hussar Regiment Nr. 4 were engaged.[14]

At 2:00 PM on 17 May, Kollowrat's attacks began. At that time, intelligence was received that Bernadotte's Saxons had arrived in Linz, having marched from Passau. Kollowrat immediately suspended the assault and determined to retreat. In fact, Bernadotte reached Linz at 7:00 AM that morning with his leading infantry and cavalry brigades. He crossed into the bridgehead in the afternoon and attacked the Austrian column on the east side, pushing it back with loss. Having disposed of Vukassovich, he turned on Sommariva on the west side and defeated his force as well.[18]

One notable feature of the fighting was a successful allied cavalry charge against an Austrian artillery battery on the Pfennigberg hill. The Württemberg Duke Louis Jäger zu Pferde Regiment and the Saxon Hussars overran the battery, capturing six guns. The Jägers were allowed to claim four of the captured pieces as prizes while the Hussars got the other two.[19] One authority wrote that Bernadotte had no more than 10,000 troops available, while Kollowrat commanded over 20,000.[18] Historian Digby Smith stated that 15,000 Austrians and 36 guns were engaged against 6,000 Saxons and 12,000 Württembergers with 22 guns.[14]

Result

The Württembergers lost 35 killed, 228 wounded, and 40 missing, for a total of 303. Saxon casualties numbered 88, with seven killed, 74 wounded, and seven captured. The Austrians counted 49 killed, 263 wounded, 455 captured, and 124 missing, for a total of 891. They also lost six guns and two ammunition wagons.[14] Another authority lists Austrian losses as 883 and four guns. After his defeat, Kollowrat fell back first to Gallneukirchen to the northeast of Linz. Later his corps marched north to Freistadt.[18] Archduke Charles failed to call the III Armeekorps to return to the main army north of Vienna[20] and it missed the Battle of Aspern-Essling on 21 and 22 May.[21]

Around 26 May, Archduke Charles recalled the III Armeekorps to join the main army opposite Vienna. Following his instructions, Kollowrat left Sommariva's division at Freistadt to observe Linz while bringing his other two divisions to link up with Charles. To insure the safety of his communications, Napoleon ordered the fortifications at the Linz bridgehead to be improved. Leaving Vandamme's Württembergers behind, Bernadotte hurried to join Napoleon with his Saxons.[22] In addition to Sommariva's force, Feldmarschall-Leutnant Emmanuel von Schustekh-Herve with 9,000 men and 13 guns had been hovering near Krems an der Donau since 10 May.[23]

At Villach on 17 May, Archduke John received orders to move against Napoleon's communications from the south.[24] These instructions proved impossible to execute because Marshal François Joseph Lefebvre defeated Feldmarschall-Leutnant Johann Gabriel Chasteler de Courcelles[25] on 13 May at the Battle of Wörgl.[26] Instead, John recalled Chasteler and Feldmarschall-Leutnant Franz Jellacic from the Tyrol in the hope of adding their forces to his weakened army. As it happened, Jellacic's division was crushed at the Battle of Sankt Michael on 25 May and only remnants joined John.[25] Chasteler escaped but never caught up with John's army in its operations against Eugène de Beauharnais' French Army of Italy.[27]

Notes

- Smith, 305. Smith named the action.

- Petre, 209

- Petre, 211-212

- Petre, 211

- Petre, 225

- Petre, 213

- Petre, 217

- Arnold, 7-15

- Petre, 256-257

- Petre, 247

- Petre, 214-215

- Petre, 266-267

- Petre, 216

- Smith, 305

- Bowden & Tarbox, 62

- Bowden & Tarbox, 149-150

- Bowden & Tarbox, 150

- Petre, 267

- Smith, 306

- Petre, 272

- Smith, 307

- Petre, 324-325

- Petre, 257

- Bowden & Tarbox, 96

- Petre, 303

- Smith, 303

- Petre, 313, 315

References

- Arnold, James R. Napoleon Conquers Austria. Westport, Conn.: Praeger Publishers, 1995. ISBN 0-275-94694-0

- Bowden, Scotty & Tarbox, Charlie. Armies on the Danube 1809. Arlington, Texas: Empire Games Press, 1980.

- Epstein, Robert M. Napoleon's Last Victory and the Emergence of Modern War. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas, 1994.

- Petre, F. Loraine. Napoleon and the Archduke Charles. New York: Hippocrene Books, (1909) 1976.

- Smith, Digby. The Napoleonic Wars Data Book. London: Greenhill, 1998. ISBN 1-85367-276-9

External sources

- The following two items are excellent sources for the full names of Austrian and French generals.

- napoleon-series.org Austrian Generals 1792-1815 by Digby Smith, compiled by Leopold Kudrna

- Broughton, Tony. napoleon-series.org Generals Who Served in the French Army during the Period 1789-1815

Other reading

- Chandler, David. The Campaigns of Napoleon. New York: Macmillan, 1966.

- Epstein, Robert M. Napoleon's Last Victory and the Emergence of Modern War. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas, 1994.

- Rickard, J. (12 Nov. 2010) historyofwar.org Battle of Linz