Integral membrane protein

An integral membrane protein (IMP) is a type of membrane protein that is permanently attached to the biological membrane. All transmembrane proteins are IMPs, but not all IMPs are transmembrane proteins.[1] IMPs comprise a significant fraction of the proteins encoded in an organism's genome.[2] Proteins that cross the membrane are surrounded by annular lipids, which are defined as lipids that are in direct contact with a membrane protein. Such proteins can only be separated from the membranes by using detergents, nonpolar solvents, or sometimes denaturing agents.

Structure

Three-dimensional structures of ~160 different integral membrane proteins have been determined at atomic resolution by X-ray crystallography or nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. They are challenging subjects for study owing to the difficulties associated with extraction and crystallization. In addition, structures of many water-soluble protein domains of IMPs are available in the Protein Data Bank. Their membrane-anchoring α-helices have been removed to facilitate the extraction and crystallization. Search integral membrane proteins in the PDB (based on gene ontology classification)

IMPs can be divided into two groups:

- Integral polytopic proteins (Transmembrane proteins)

- Integral monotopic proteins

Integral polytopic protein

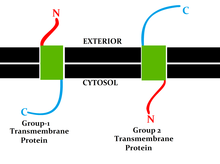

The most common type of IMP is the transmembrane protein (TM), which spans the entire biological membrane. Single-pass membrane proteins cross the membrane only once, while multi-pass membrane proteins weave in and out, crossing several times. Single pass TM proteins can be categorized as Type I, which are positioned such that their carboxyl-terminus is towards the cytosol, or Type II, which have their amino-terminus towards the cytosol. Type III proteins have multiple transmembrane domains in a single polypeptide, while type IV consists of several different polypeptides assembled together in a channel through the membrane. Type V proteins are anchored to the lipid bilayer through covalently linked lipids. Finally Type VI proteins have both transmembrane domains and lipid anchors.[3]

Integral monotopic proteins

Integral monotopic proteins are associated with the membrane from one side but do not span the lipid bilayer completely.

Determination of protein structure

The Protein Structure Initiative (PSI), funded by the U.S. National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS), part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), has among its aim to determine three-dimensional protein structures and to develop techniques for use in structural biology, including for membrane proteins. Homology modeling can be used to construct an atomic-resolution model of the "target" integral protein from its amino acid sequence and an experimental three-dimensional structure of a related homologous protein. This procedure has been extensively used for ligand-G protein–coupled receptors (GPCR) and their complexes.[4]

Function

IMPs include transporters, linkers, channels, receptors, enzymes, structural membrane-anchoring domains, proteins involved in accumulation and transduction of energy, and proteins responsible for cell adhesion. Classification of transporters can be found in Transporter Classification Database.[5]

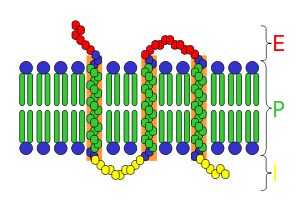

As an example of the relationship between the IMP (in this case the bacterial phototrapping pigment, bacteriorhodopsin) and the membrane formed by the phospholipid bilayer is illustrated below. In this case the integral membrane protein spans the phospholipid bilayer seven times. The part of the protein that is embedded in the hydrophobic regions of the bilayer are alpha helical and composed of predominantly hydrophobic amino acids. The C terminal end of the protein is in the cytosol while the N terminal region is in the outside of the cell. A membrane that contains this particular protein is able to function in photosynthesis.[6]

Examples

Examples of integral membrane proteins:

- Insulin receptor

- Some types of cell adhesion proteins or cell adhesion molecules (CAMs) such as integrins, cadherins, NCAMs, or selectins

- Some types of receptor proteins

- Glycophorin

- Rhodopsin

- Band 3

- CD36

- Glucose Permease

- Ion channels and Gates

- Gap junction Proteins

- G protein coupled receptors (e.g., Beta-adrenergic receptor)

- Seipin

See also

References

- Steven R. Goodman (2008). Medical cell biology. Academic Press. pp. 37–. ISBN 978-0-12-370458-0. Retrieved 24 November 2010.

- Wallin E, von Heijne G (1998). "Genome-wide analysis of integral membrane proteins from eubacterial, archaean, and eukaryotic organisms". Protein Science. 7 (4): 1029–38. doi:10.1002/pro.5560070420. PMC 2143985. PMID 9568909.

- Nelson, D. L., & Cox, M. M. (2008). Principles of Biochemistry (5th ed., p. 377). New York, NY: W.H. Freeman and Company.

- Fruchart-Marquer C, Fruchart-Gaillard C, Letellier G, Marcon E, Mourier G, Zinn-Justin S, Ménez A, Servent D, Gilquin B (September 2011). "Structural model of ligand-G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) complex based on experimental double mutant cycle data: MT7 snake toxin bound to dimeric hM1 muscarinic receptor". J Biol Chem. 286 (36): 31661–75. doi:10.1074/jbc.M111.261404. PMC 3173127. PMID 21685390.

- Saier MH, Yen MR, Noto K, Tamang DG, Elkan C (January 2009). "The Transporter Classification Database: recent advances". Nucleic Acids Res. 37 (Database issue): D274–8. doi:10.1093/nar/gkn862. PMC 2686586. PMID 19022853.

- "Integral membrane proteins". academic.brooklyn.cuny.edu. Archived from the original on 1 February 2015. Retrieved 29 January 2015.