Abugida

An abugida /ɑːbʊˈɡiːdə/ (![]()

| Writing systems |

|---|

|

| Types |

| Related topics |

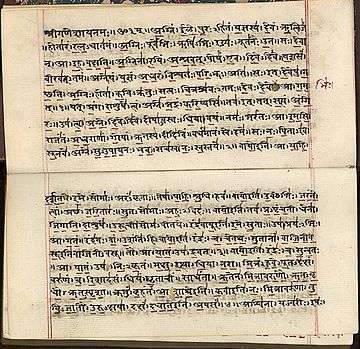

Abugidas include the extensive Brahmic family of scripts of Tibet, South and Southeast Asia, Semitic Ethiopic scripts, and Canadian Aboriginal syllabics.

As is the case for syllabaries, the units of the writing system may consist of the representations both of syllables and of consonants. For scripts of the Brahmic family, the term akshara is used for the units.

’Äbugida is an Ethiopian name for the Ge‘ez script, taken from four letters of that script, 'ä bu gi da, in much the same way that abecedary is derived from Latin a be ce de, abjad is derived from the Arabic a b j d, and alphabet is derived from the names of the two first letters in the Greek alphabet, alpha and beta. Abugida as a term in linguistics was proposed by Peter T. Daniels in his 1990 typology of writing systems.[1] As Daniels used the word, an abugida is in contrast with a syllabary, where letters with shared consonants or vowels show no particular resemblance to one another, and also with an alphabet proper, where independent letters are used to denote both consonants and vowels. The term alphasyllabary was suggested for the Indic scripts in 1997 by William Bright, following South Asian linguistic usage, to convey the idea that "they share features of both alphabet and syllabary."[2][3]

Abugidas were long considered to be syllabaries, or intermediate between syllabaries and alphabets, and the term syllabics is retained in the name of Canadian Aboriginal Syllabics. Other terms that have been used include neosyllabary (Février 1959), pseudo-alphabet (Householder 1959), semisyllabary (Diringer 1968; a word that has other uses) and syllabic alphabet (Coulmas 1996; this term is also a synonym for syllabary).[3]

General description

The formal definitions given by Daniels and Bright for abugida and alphasyllabary differ; some writing systems are abugidas but not alphasyllabaries, and some are alphasyllabaries but not abugidas. An abugida is defined as "a type of writing system whose basic characters denote consonants followed by a particular vowel, and in which diacritics denote other vowels".[4] (This 'particular vowel' is referred to as the inherent or implicit vowel, as opposed to the explicit vowels marked by the 'diacritics'.) An alphasyllabary is defined as "a type of writing system in which the vowels are denoted by subsidiary symbols not all of which occur in a linear order (with relation to the consonant symbols) that is congruent with their temporal order in speech".[4] Bright did not require that an alphabet explicitly represent all vowels.[3] ʼPhags-pa is an example of an abugida that is not an alphasyllabary, and modern Lao is an example of an alphasyllabary that is not an abugida, for its vowels are always explicit.

This description is expressed in terms of an abugida. Formally, an alphasyllabary that is not an abugida can be converted to an abugida by adding a purely formal vowel sound that is never used and declaring that to be the inherent vowel of the letters representing consonants. This may formally make the system ambiguous, but in 'practice' this is not a problem, for then the interpretation with the never used inherent vowel sound will always be a wrong interpretation. Note that the actual pronunciation may be complicated by interactions between the sounds apparently written just as the sounds of the letters in the English words wan, gem and war are affected by neighbouring letters.

The fundamental principles of an abugida apply to words made up of consonant-vowel (CV) syllables. The syllables are written as a linear sequences of the units of the script. Each syllable is either a letter that represents the sound of a consonant and the inherent vowel, or a letter with a modification to indicate the vowel, either by means of diacritics, or by changes in the form of the letter itself. If all modifications are by diacritics and all diacritics follow the direction of the writing of the letters, then the abugida is not an alphasyllabary.

However, most languages have words that are more complicated than a sequence of CV syllables, even ignoring tone.

The first complication is syllables that consist of just a vowel (V). This issue does not arise in some languages because every syllable starts with a consonant. This is common in Semitic languages and in languages of mainland SE Asia, and for such languages this issue need not arise. For some languages, a zero consonant letter is used as though every syllable began with a consonant. For other languages, each vowel has a separate letter that is used for each syllable consisting of just the vowel. These letters are known as independent vowels, and are found in most Indic scripts. These letters may be quite different from the corresponding diacritics, which by contrast are known as dependent vowels. As a result of the spread of writing systems, independent vowels may be used to represent syllables beginning with a glottal stop, even for non-initial syllables.

The next two complications are sequences of consonants before a vowel (CCV) and syllables ending in a consonant (CVC). The simplest solution, which is not always available, is to break with the principle of writing words as a sequence of syllables and use a unit representing just a consonant (C). This unit may be represented with:

- a modification that explicitly indicates the lack of a vowel (virama),

- a lack of vowel marking (often with ambiguity between no vowel and a default inherent vowel),

- vowel marking for a short or neutral vowel such as schwa (with ambiguity between no vowel and that short or neutral vowel), or

- a visually unrelated letter.

In a true abugida, the lack of distinctive marking may result from the diachronic loss of the inherent vowel, e.g. by syncope and apocope in Hindi.

When not handled by decomposition into C + CV, CCV syllables are handled by combining the two consonants. In the Indic scripts, the earliest method was simply to arrange them vertically, but the two consonants may merge as a conjunct consonant letters, where two or more letters are graphically joined in a ligature, or otherwise change their shapes. Rarely, one of the consonants may be replaced by a gemination mark, e.g. the Gurmukhi addak. When they are arranged vertically, as in Burmese or Khmer, they are said to be 'stacked'. Often there has been a change to writing the two consonants side by side. In the latter case, the fact of combination may be indicated by a diacritic on one of the consonants or a change in the form of one of the consonants, e.g. the half forms of Devanagari. Generally, the reading order is top to bottom or the general reading order of the script, but sometimes the order is reversed.

The division of a word into syllables for the purposes of writing does not always accord with the natural phonetics of the language. For example, Brahmic scripts commonly handle a phonetic sequence CVC-CV as CV-CCV or CV-C-CV. However, sometimes phonetic CVC syllables are handled as single units, and the final consonant may be represented:

- in much the same way as the second consonant in CCV, e.g. in the Tibetan, Khmer[5] and Tai Tham[6] scripts. The positioning of the components may be slightly different, as in Khmer and Tai Tham.

- by a special dependent consonant sign, which may be a smaller or differently placed version of the full consonant letter, or may be a distinct sign altogether.

- not at all. For example, repeated consonants need not be represented, homorganic nasals may be ignored, and in Philippine scripts, the syllable-final consonant was traditionally never represented.[7]

More complicated unit structures (e.g. CC or CCVC) are handled by combining the various techniques above.

Family-specific features

There are three principal families of abugidas, depending on whether vowels are indicated by modifying consonants by diacritics, distortion, or orientation.[8]

- The oldest and largest is the Brahmic family of India and Southeast Asia, in which vowels are marked with diacritics and syllable-final consonants, when they occur, are indicated with ligatures, diacritics, or with a special vowel-canceling mark.

- In the Ethiopic family, vowels are marked by modifying the shapes of the consonants, and one of the vowel-forms serves additionally to indicate final consonants.

- In the Cree family, vowels are marked by rotating or flipping the consonants, and final consonants are indicated with either special diacritics or superscript forms of the main initial consonants.

Tāna of the Maldives has dependent vowels and a zero vowel sign, but no inherent vowel.

| Feature | North Indic | South Indic | Tāna | Ethiopic | Canadian Aboriginal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vowel representation after consonant | Dependent sign (diacritic) in distinct position per vowel | Fused diacritic | Rotate/reflect | ||

| Initial vowel representation | Distinct inline letter per vowel[lower-alpha 1] | Glottal stop or zero consonant plus dependent vowel in Tāna and mainland Southeast Asia[lower-alpha 2] | Glottal stop plus dependent | Zero consonant plus dependent | |

| Inherent vowel (value of no vowel sign) | [ə], [ɔ], [a], or [o][lower-alpha 3] | No | [ɐ][10] | N/A | |

| Zero vowel sign (sign for no value) | Often | Always used when no final vowel[lower-alpha 4] | Ambiguous with ə ([ɨ]) | Shrunk or separate letter[lower-alpha 5] | |

| Consonant cluster | Conjunct[lower-alpha 6] | Stacked or separate[lower-alpha 7] | Separate | ||

| Final consonant (not sign) | Inline[lower-alpha 8] | Inline | Inline | ||

| Distinct final sign | Only for ṃ, ḥ[lower-alpha 9][lower-alpha 10] | No | Only in Western | ||

| Final sign position | Inline or top | Inline, top or occasionally bottom | N/A | Raised or inline | |

| |||||

Indic (Brahmic)

Indic scripts originated in India and spread to Southeast Asia. All surviving Indic scripts are descendants of the Brahmi alphabet. Today they are used in most languages of South Asia (although replaced by Perso-Arabic in Urdu, Kashmiri and some other languages of Pakistan and India), mainland Southeast Asia (Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, and Cambodia), and Indonesian archipelago (Javanese, Balinese, Sundanese, etc.). The primary division is into North Indic scripts used in Northern India, Nepal, Tibet and Bhutan, and Southern Indic scripts used in South India, Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia. South Indic letter forms are very rounded; North Indic less so, though Odia, Golmol and Litumol of Nepal script are rounded. Most North Indic scripts' full letters incorporate a horizontal line at the top, with Gujarati and Odia as exceptions; South Indic scripts do not.

Indic scripts indicate vowels through dependent vowel signs (diacritics) around the consonants, often including a sign that explicitly indicates the lack of a vowel. If a consonant has no vowel sign, this indicates a default vowel. Vowel diacritics may appear above, below, to the left, to the right, or around the consonant.

The most widely used Indic script is Devanagari, shared by Hindi, Bhojpuri, Marathi, Konkani, Nepali, and often Sanskrit. A basic letter such as क in Hindi represents a syllable with the default vowel, in this case ka ([kə]). In some languages, including Hindi, it becomes a final closing consonant at the end of a word, in this case k. The inherent vowel may be changed by adding vowel mark (diacritics), producing syllables such as कि ki, कु ku, के ke, को ko.

| position | syllable | pronunciation | base form | script |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| above | के | /keː/ | क /k(a)/ | Devanagari |

| below | कु | /ku/ | ||

| left | कि | /ki/ | ||

| right | को | /koː/ | ||

| around | கௌ | /kau̯/ | க /ka/ | Tamil |

| surround | កៀ | /kie/ | ក /kɑː/ | Khmer |

| within | ಕಿ | /ki/ | ಕ /ka/ | Kannada |

| within | కి | /ki/ | క /ka/ | Telugu |

| below and extend to the right | ꦏꦾ | /kja/ | ꦏ /ka/ | Javanese |

| below and extend to the left | ꦏꦿꦸ | /kru/ | ꦏ /ka/ | Javanese |

In many of the Brahmic scripts, a syllable beginning with a cluster is treated as a single character for purposes of vowel marking, so a vowel marker like ि -i, falling before the character it modifies, may appear several positions before the place where it is pronounced. For example, the game cricket in Hindi is क्रिकेट cricket; the diacritic for /i/ appears before the consonant cluster /kr/, not before the /r/. A more unusual example is seen in the Batak alphabet: Here the syllable bim is written ba-ma-i-(virama). That is, the vowel diacritic and virama are both written after the consonants for the whole syllable.

In many abugidas, there is also a diacritic to suppress the inherent vowel, yielding the bare consonant. In Devanagari, क् is k, and ल् is l. This is called the virāma or halantam in Sanskrit. It may be used to form consonant clusters, or to indicate that a consonant occurs at the end of a word. Thus in Sanskrit, a default vowel consonant such as क does not take on a final consonant sound. Instead, it keeps its vowel. For writing two consonants without a vowel in between, instead of using diacritics on the first consonant to remove its vowel, another popular method of special conjunct forms is used in which two or more consonant characters are merged to express a cluster, such as Devanagari: क्ल kla. (Note that some fonts display this as क् followed by ल, rather than forming a conjunct. This expedient is used by ISCII and South Asian scripts of Unicode.) Thus a closed syllable such as kal requires two aksharas to write.

The Róng script used for the Lepcha language goes further than other Indic abugidas, in that a single akshara can represent a closed syllable: Not only the vowel, but any final consonant is indicated by a diacritic. For example, the syllable [sok] would be written as something like s̥̽, here with an underring representing /o/ and an overcross representing the diacritic for final /k/. Most other Indic abugidas can only indicate a very limited set of final consonants with diacritics, such as /ŋ/ or /r/, if they can indicate any at all.

Ethiopic

%2C_15th_century_(The_S.S._Teacher's_Edition-The_Holy_Bible_-_Plate_XII%2C_1).jpg)

In Ethiopic (where the term abugida originates[1]) the diacritics have been fused to the consonants to the point that they must be considered modifications of the form of the letters. Children learn each modification separately, as in a syllabary; nonetheless, the graphic similarities between syllables with the same consonant is readily apparent, unlike the case in a true syllabary.

Though now an abugida, the Ge'ez script, until the advent of Christianity (ca. AD 350), had originally been what would now be termed an abjad. In the Ge'ez abugida (or fidel), the base form of the letter (also known as fidel) may be altered. For example, ሀ hä [hə] (base form), ሁ hu (with a right-side diacritic that doesn't alter the letter), ሂ hi (with a subdiacritic that compresses the consonant, so it is the same height), ህ hə [hɨ] or [h] (where the letter is modified with a kink in the left arm).

Canadian Aboriginal syllabics

In the family known as Canadian Aboriginal syllabics, which was inspired by the Devanagari script of India, vowels are indicated by changing the orientation of the syllabogram. Each vowel has a consistent orientation; for example, Inuktitut ᐱ pi, ᐳ pu, ᐸ pa; ᑎ ti, ᑐ tu, ᑕ ta. Although there is a vowel inherent in each, all rotations have equal status and none can be identified as basic. Bare consonants are indicated either by separate diacritics, or by superscript versions of the aksharas; there is no vowel-killer mark.

Borderline cases

Vowelled abjads

Consonantal scripts ("abjads") are normally written without indication of many vowels. However, in some contexts like teaching materials or scriptures, Arabic and Hebrew are written with full indication of vowels via diacritic marks (harakat, niqqud) making them effectively alphasyllabaries. The Brahmic and Ethiopic families are thought to have originated from the Semitic abjads by the addition of vowel marks.

The Arabic scripts used for Kurdish in Iraq and for Uyghur in Xinjiang, China, as well as the Hebrew script of Yiddish, are fully vowelled, but because the vowels are written with full letters rather than diacritics (with the exception of distinguishing between /a/ and /o/ in the latter) and there are no inherent vowels, these are considered alphabets, not abugidas.

Phagspa

The imperial Mongol script called Phagspa was derived from the Tibetan abugida, but all vowels are written in-line rather than as diacritics. However, it retains the features of having an inherent vowel /a/ and having distinct initial vowel letters.

Pahawh

Pahawh Hmong is a non-segmental script that indicates syllable onsets and rimes, such as consonant clusters and vowels with final consonants. Thus it is not segmental and cannot be considered an abugida. However, it superficially resembles an abugida with the roles of consonant and vowel reversed. Most syllables are written with two letters in the order rime–onset (typically vowel-consonant), even though they are pronounced as onset-rime (consonant-vowel), rather like the position of the /i/ vowel in Devanagari, which is written before the consonant. Pahawh is also unusual in that, while an inherent rime /āu/ (with mid tone) is unwritten, it also has an inherent onset /k/. For the syllable /kau/, which requires one or the other of the inherent sounds to be overt, it is /au/ that is written. Thus it is the rime (vowel) that is basic to the system.

Meroitic

It is difficult to draw a dividing line between abugidas and other segmental scripts. For example, the Meroitic script of ancient Sudan did not indicate an inherent a (one symbol stood for both m and ma, for example), and is thus similar to Brahmic family of abugidas. However, the other vowels were indicated with full letters, not diacritics or modification, so the system was essentially an alphabet that did not bother to write the most common vowel.

Shorthand

Several systems of shorthand use diacritics for vowels, but they do not have an inherent vowel, and are thus more similar to Thaana and Kurdish script than to the Brahmic scripts. The Gabelsberger shorthand system and its derivatives modify the following consonant to represent vowels. The Pollard script, which was based on shorthand, also uses diacritics for vowels; the placements of the vowel relative to the consonant indicates tone. Pitman shorthand uses straight strokes and quarter-circle marks in different orientations as the principal "alphabet" of consonants; vowels are shown as light and heavy dots, dashes and other marks in one of 3 possible positions to indicate the various vowel-sounds. However, to increase writing speed, Pitman has rules for "vowel indication"[11] using the positioning or choice of consonant signs so that writing vowel-marks can be dispensed with.

Development

As the term alphasyllabary suggests, abugidas have been considered an intermediate step between alphabets and syllabaries. Historically, abugidas appear to have evolved from abjads (vowelless alphabets). They contrast with syllabaries, where there is a distinct symbol for each syllable or consonant-vowel combination, and where these have no systematic similarity to each other, and typically develop directly from logographic scripts. Compare the examples above to sets of syllables in the Japanese hiragana syllabary: か ka, き ki, く ku, け ke, こ ko have nothing in common to indicate k; while ら ra, り ri, る ru, れ re, ろ ro have neither anything in common for r, nor anything to indicate that they have the same vowels as the k set.

Most Indian and Indochinese abugidas appear to have first been developed from abjads with the Kharoṣṭhī and Brāhmī scripts; the abjad in question is usually considered to be the Aramaic one, but while the link between Aramaic and Kharosthi is more or less undisputed, this is not the case with Brahmi. The Kharosthi family does not survive today, but Brahmi's descendants include most of the modern scripts of South and Southeast Asia.

Ge'ez derived from a different abjad, the Sabean script of Yemen; the advent of vowels coincided with the introduction of Christianity about AD 350.[10] The Ethiopic script is the elaboration of an abjad.

The Cree syllabary was invented with full knowledge of the Devanagari system.

The Meroitic script was developed from Egyptian hieroglyphs, within which various schemes of 'group writing'[12] had been used for showing vowels.

List of abugidas

- Brahmic family, descended from Brāhmī (c. 6th century BC)

- Ahom

- Assamese

- Brahmi – Sanskrit, Prakrit

- Balinese

- Batak – Toba and other Batak languages

- Baybayin – Ilocano, Pangasinan, Tagalog, Bikol languages, Visayan languages, and possibly other Philippine languages

- Bengali[13] – Bengali, Assamese, Meithei, Bishnupriya Manipuri, Kokborok, Khasi, Bodo language

- Bhaiksuki

- Buhid

- Burmese – Burmese, Karen languages, Mon, and Shan

- Cham

- Chakma

- Devanagari – Hindi, Sanskrit, Marathi, Nepali, and many other languages of northern India

- Dhives Akuru

- Grantha – Sanskrit

- Gujarati – Gujarāti, Kachchi

- Gurmukhi script – Punjabi

- Hanunó’o

- Javanese

- Kaithi

- Kaganga – Lampung, Rencong, Rejang

- Kannada – Kannada, Tulu, Konkani, Kodava

- Kawi

- Khojki

- Khotanese

- Khudawadi

- Khmer

- Kolezhuthu – Tamil, Malayalam

- Kulitan

- Lao

- Lepcha

- Leke

- Limbu

- Lontara’ – Buginese, Makassar, and Mandar

- Mahajani

- Malayalam – Malayalam

- Malayanma – Malayalam

- Marchen – Zhang-Zhung

- Meetei Mayek

- Meroitic

- Modi – Marathi

- Multani – Saraiki

- Nandinagari – Sanskrit

- Newar – Nepal Bhasa, Sanskrit

- New Tai Lue

- Odia

- Pallava script – Tamil, Sanskrit, various Prakrits

- Phags-pa – Mongolian, Chinese, and other languages of the Yuan dynasty Mongol Empire

- Ranjana – Nepal Bhasa, Sanskrit

- Sharada – Sanskrit

- Siddham – Sanskrit

- Sinhala

- Sourashtra

- Soyombo

- Sundanese

- Syloti Nagri – Sylheti

- Tagbanwa – Palawan languages

- Tai Le

- Tai Dam

- Tai Tham – Khün, and Northern Thai

- Takri

- Tamil

- Telugu

- Thai

- Tibetan

- Tigalari – Sanskrit

- Tirhuta – Maithili

- Tocharian

- Vatteluttu – Tamil, Malayalam

- Zanabazar Square

- Zhang zhung scripts

- Kharoṣṭhī, from the 3rd century BC

- Ge'ez, from the 4th century AD

- Canadian Aboriginal syllabics

- Pollard script

- Pitman shorthand

Abugida-like scripts

- Meroitic (an alphabet with an inherent vowel) – Meroitic, Old Nubian (possibly)

- Thaana (abugida with no inherent vowel)

References

- Daniels, Peter T. (October–December 1990), "Fundamentals of Grammatology", Journal of the American Oriental Society, 119 (4): 727–731, doi:10.2307/602899, JSTOR 602899

- He describes this term as "formal", i.e., more concerned with graphic arrangement of symbols, whereas abugida was "functional", putting the focus on sound–symbol correspondence. However, this is not a distinction made in the literature.

- William Bright (2000:65–66): "A Matter of Typology: Alphasyllabaries and Abugidas". In: Studies in the Linguistic Sciences. Volume 30, Number 1, pages 63–71

- Glossary of Daniels & Bright (1996) The World's Writing Systems

- "The Unicode Standard, Version 8.0" (pdf). August 2015. Section 16.4 Khmer, Subscript Consonants.

- Everson, Michael; Hosken, Martin (6 August 2006). "Proposal for encoding the Lanna script in the BMP of the UCS" (PDF). Working Group Document. International Organization for Standardization.

- Joel C. Kuipers & Ray McDermott, "Insular Southeast Asian Scripts". In Daniels & Bright (1996) The World's Writing Systems

- John D. Berry (2002:19) Language Culture Type

- Everson, Michael (6 August 2006). "Proposal for encoding the Cham script in the BMP of the UCS" (PDF). Unicode Consortium.

- Getatchew Haile, "Ethiopic Writing". In Daniels & Bright (1996) The World's Writing Systems

- "The Joy of Pitman Shorthand". pitmanshorthand.homestead.com.

- James Hoch (1994) Semitic Words in Egyptian Texts of the New Kingdom and Third Intermediate Periods

- "ScriptSource – Bengali (Bangla)". www.scriptsource.org. Retrieved 9 May 2019.

- "Ihathvé Sabethired". www.omniglot.com.

External links

- Syllabic alphabets – Omniglot's list of abugidas, including examples of various writing systems

- Alphabets – list of abugidas and other scripts (in Spanish)

- Comparing Devanagari with Burmese, Khmer, Thai, and Tai Tham scripts