Insular script

Insular script was a medieval script system invented in Ireland that spread to Anglo-Saxon England and continental Europe under the influence of Irish Christianity. Irish missionaries took the script to continental Europe, where they founded monasteries such as Bobbio. The scripts were also used in monasteries like Fulda, which were influenced by English missionaries. They are associated with insular art, of which most surviving examples are illuminated manuscripts. It greatly influenced Irish orthography and modern Gaelic scripts in handwriting and typefaces.

| Insular (Gaelic) script | |

|---|---|

The beginning of the Gospel of Mark from the Book of Durrow | |

| Type | |

| Languages | Latin, Irish, English |

Time period | fl. 600–850 AD |

Parent systems | Latin script

|

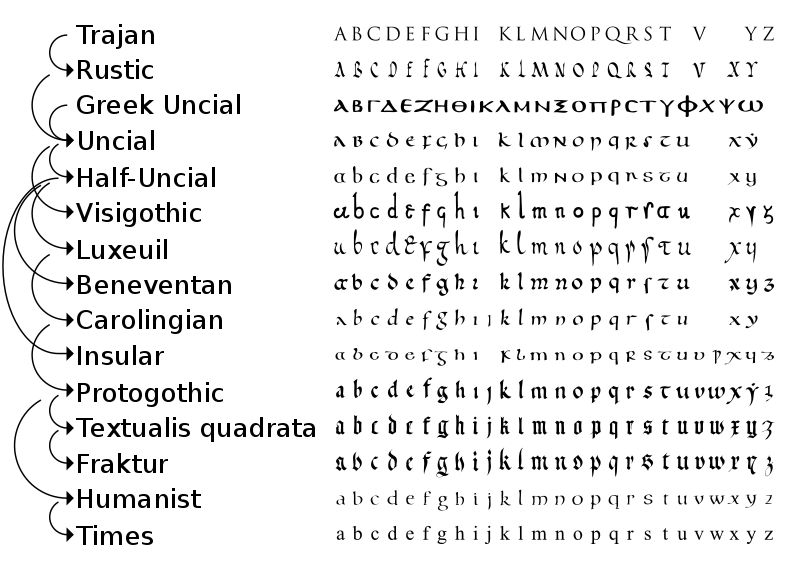

Insular script comprised a family of different scripts used for different functions. At the top of the hierarchy was the Insular half-uncial (or "Insular majuscule"), used for important documents and sacred text. The full uncial, in a version called "English uncial", was used in some English centres. Then "in descending order of formality and increased speed of writing" came "set minuscule", "cursive minuscule" and "current minuscule". These were used for non-scriptural texts, letters, accounting records, notes, and all the other types of written documents.[1]

Origin

The scripts developed in Ireland in the 7th century and were used as late as the 19th century, though its most flourishing period fell between 600 and 850. They were closely related to the uncial and half-uncial scripts, their immediate influences; the highest grade of Insular script is the majuscule Insular half-uncial, which is closely derived from Continental half-uncial script.

Appearance

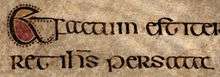

Works written in Insular scripts commonly use large initial letters surrounded by red ink dots (although this is also true of other scripts written in Ireland and England). Letters following a large initial at the start of a paragraph or section often gradually diminish in size as they are written across a line or a page, until the normal size is reached, which is called a "diminuendo" effect, and is a distinctive insular innovation, which later influenced Continental illumination style. Letters with ascenders (b, d, h, l, etc.) are written with triangular or wedge-shaped tops. The bows of letters such as b, d, p, and q are very wide. The script uses many ligatures and has many unique scribal abbreviations, along with many borrowings from Tironian notes.

Insular script was spread to England by the Hiberno-Scottish mission; previously, uncial script had been brought to England by Augustine of Canterbury. The influences of both scripts produced the Insular script system. Within this system, the palaeographer Julian Brown identified five grades, with decreasing formality:

- Insular half-uncial, or "Irish majuscule": the most formal; became reserved for rubrics (highlighted directions) and other displays after the 9th century.[2]

- Insular hybrid minuscule: the most formal of the minuscules, came to be used for formal church books when use of the "Irish majuscule" diminished.[2]

- Insular set minuscule

- Insular cursive minuscule

- Insular current minuscule: the least formal;[3] current here means ‘running’ (rapid).[4]

Brown has also postulated two phases of development for this script, Phase II being mainly influenced by Roman Uncial examples, developed at Wearmouth-Jarrow and typified by the Lindisfarne Gospels.[5]

Usage

Insular script was used not only for Latin religious books, but also for every other kind of book, including vernacular works. Examples include the Book of Kells, the Cathach of St. Columba, the Ambrosiana Orosius, the Durham Gospel Fragment, the Book of Durrow, the Durham Gospels, the Echternach Gospels, the Lindisfarne Gospels, the Lichfield Gospels, the St. Gall Gospel Book, and the Book of Armagh.

Insular script was influential in the development of Carolingian minuscule in the scriptoria of the Carolingian empire.

In Ireland, Insular script was superseded in c. 850 by Late Insular script; in England, it was followed by a form of Caroline minuscule.

The Tironian et ⟨⁊⟩ — equivalent of ampersand (&) — was in widespread use in the script (meaning agus ‘and’ in Irish and ond ‘and’ in Old English) and is occasionally continued in modern Gaelic typefaces derived from insular script.

Unicode

There are only a few insular letters encoded, these are shown below, but most fonts will only display U+1D79 (ᵹ). To display the other characters there are several fonts that may be used; three free ones that support these characters are Junicode, Montagel, and Quivira.

According to Michael Everson, in the 2006 Unicode proposal for these characters:[6]

To write text in an ordinary Gaelic font, only ASCII letters should be used, the font making all the relevant substitutions; the insular letters [proposed here] are for use only by specialists who require them for particular purposes.

| Insular letters in Unicode[1][2] | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+1D7x | ᵹ | |||||||||||||||

| U+1DDx | ◌ᷘ | |||||||||||||||

| U+204x | ⁊ | |||||||||||||||

| U+A77x | Ꝺ | ꝺ | Ꝼ | ꝼ | Ᵹ | Ꝿ | ꝿ | |||||||||

| U+A78x | Ꞃ | ꞃ | Ꞅ | ꞅ | Ꞇ | ꞇ | ||||||||||

Notes

| ||||||||||||||||

See also

- Carolingian minuscule

- Gaelic type

- Hiberno-Saxon art

- Insular G

- Latin delta

- Tironian et

- Irish orthography

- List of Hiberno-Saxon illustrated manuscripts

References

- Brown, Michelle P., Manuscripts from the Anglo-Saxon Age, p. 13 (quoted), 2007, British Library, ISBN 978-0-7123-0680-5

- Saunders, Corinne (2010). A Companion to Medieval Poetry. John Wiley & Sons. p. 52. ISBN 978-1-4443-1910-1.

- Michael Lapidge; John Blair; Simon Keynes; Donald Scragg (2013). The Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England. John Wiley & Sons. p. 423. ISBN 978-1-118-31609-2.: Entry "Script, Anglo-Saxon"

- "current, a.". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.) (definition e.)

- Brown, Thomas Julian (1993). J. Bately; M. Brown; J. Roberts. (eds.). A Palaeographer's View. Selected Writings of Julian Brown. London: Harvey Miller Publishers.

- Everson, Michael (2006-08-06). "N3122: Proposal to add Latin letters and a Greek symbol to the UCS" (PDF). ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2. Retrieved 2016-11-22.

Further reading

- 'Manual of Latin Palaeography' (A comprehensive PDF file containing 82 pages profusely illustrated, June 2014).

External links

- Pfeffer Mediæval An insular minuscule as a Unicode font (strictly speaking, a Carolingian minuscule with a set of insular variants)