Scriptorium

Scriptorium (/skrɪpˈtɔːriəm/ (![]()

The functional outset

When monastic institutions arose in the early 6th century (the first European monastic writing dates from 517), they defined European literary culture and selectively preserved the literary history of the West. Monks copied Jerome's Latin Vulgate Bible and the commentaries and letters of early Church Fathers for missionary purposes as well as for use within the monastery.

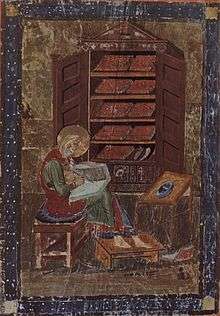

In the copying process, there was typically a division of labor among the monks who readied the parchment for copying by smoothing and chalking the surface, those who ruled the parchment and copied the text, and those who illuminated the text. Sometimes a single monk would engage in all of these stages to prepare a manuscript.[4] The illuminators of manuscripts worked in collaboration with scribes in intricate varieties of interaction that preclude any simple understanding of monastic manuscript production.[5]

The products of the monasteries provided a valuable medium of exchange. Comparisons of characteristic regional, periodic as well as contextual styles of handwriting do reveal social and cultural connections among them, as new hands developed and were disseminated by travelling individuals, respectively what these individuals represented, and by the examples of manuscripts that passed from one cloister to another. Recent studies follow the approach, that scriptoria developed in relative isolation, to the extent that the paleographer is sometimes able to identify the product of each writing centre and to date it accordingly.[6]

By the start of the 13th century secular workshops developed,[7] where professional scribes stood at writing-desks to work the orders of customers, and during the Late Middle Ages the praxis of writing was becoming not only confined to being generally a monastic or regal activity. However, the practical consequences of private workshops, and as well the invention of the printing press vis-a-vis monastic scriptoria is a complex theme.[8]

The physical scriptorium

Much as medieval libraries do not correspond to the exalted sketches from Umberto Eco's "Name of the Rose,”[10] it seems that ancient written accounts, as well as surviving buildings, and archaeological excavations do not invariably attest to the evidence of scriptoria.[11] Scriptoria in the physical sense of a room set aside for the purpose perhaps mostly existed in response to specific scribal projects; for example, when a monastic (and) or regal institution wished a large number of texts copied.

References in modern scholarly writings to 'scriptoria' typically refer to the collective written output of a monastery, somewhat like the chancery in the early regal times is taken to refer to a specific fashion of modelling formulars, but especially traditional is the view that scriptoria was a necessary adjunct to a library, as per the entry in du Cange, 1678 'scriptorium'.[12]

San Giovanni Evangelista, Rimini

At this church whose patron was Galla Placidia (died 450), paired rectangular chambers flanking the apse, accessible only from each aisle, have been interpreted as paired (Latin and Greek) libraries and perhaps scriptoria.[13] The well-lit niches .5 meter deep, provisions for hypocausts beneath the floors to keep the spaces dry, have prototypes in the architecture of Roman libraries.[14]

Cassiodorus and the Vivarium

The monastery built in the second quarter of the 6th century under the supervision of Cassiodorus at the Vivarium near Squillace in southern Italy contained a scriptorium, for the purpose of collecting, copying, and preserving texts.

Cassiodorus' description of his monastery contained a purpose-built scriptorium, with a sundial, a water-clock, and a "perpetual lamp," that is, one that supplied itself with oil from a reservoir.[15] The scriptorium would also have contained desks where the monks could sit and copy texts, as well as the necessary ink wells, penknives, and quills. Cassiodorus also established a library where, at the end of the Roman Empire, he attempted to bring Greek learning to Latin readers and to preserve texts both sacred and secular for future generations. As its unofficial librarian, Cassiodorus collected as many manuscripts as he could, he also wrote treatises aimed at instructing his monks in the proper uses of texts. In the end, however, the library at the Vivarium was dispersed and lost, though it was still active around 630.[16]

Cistercians

The scriptoria of the Cistercian order seem to have been similar to those of the Benedictines. The mother house at Cîteaux, one of the best-documented high-medieval scriptoria, developed a severe "house style" in the first half of the 12th century. The 12th-century scriptorium of Cîteaux and its products, in the context of Cistercian scriptoria, have been studied by Yolanta Załuska, L'enluminure et le scriptorium de Cîteaux au XIIe siècle (Brecht:Cîteaux) 1989.

Institutions

In Byzantium or Eastern Roman Empire learning maintained importance and numerous monastic 'scriptoria' were known for producing Bible/Gospel illuminations, along with workshops that copied numerous classical and Hellenistic works.[17] Records show that one such monastic community was that of Mount Athos, which maintained a variety of illuminated manuscripts and ultimately accumulated over 10,000 books.[17]

Benedictines

Cassiodorus' contemporary, Benedict of Nursia, allowed his monks to read the great works of the pagans in the monastery he founded at Monte Cassino in 529. The creation of a library here initiated the tradition of Benedictine scriptoria, where the copying of texts not only provided materials needed in the routines of the community and served as work for hands and minds otherwise idle, but also produced a marketable end-product. Saint Jerome stated that the products of the scriptorium could be a source of revenue for the monastic community, but Benedict cautioned, "If there be skilled workmen in the monastery, let them work at their art in all humility".[18]

In the earliest Benedictine monasteries, the writing room was actually a corridor open to the central quadrangle of the cloister.[19] The space could accommodate about twelve monks, who were protected from the elements only by the wall behind them and the vaulting above. Monasteries built later in the Middle Ages placed the scriptorium inside, near the heat of the kitchen or next to the calefactory. The warmth of the later scriptoria served as an incentive for unwilling monks to work on the transcription of texts (since the charter house was rarely heated).

St. Gall

The Benedictine Plan of St. Gall is a sketch of an idealised monastery dating from 819–826, which shows the scriptorium and library attached to the northeast corner of the main body of the church; this is not reflected by the evidence of surviving monasteries. Although the purpose of the plan is unknown, it clearly shows the desirability of scriptoria within a wider body of monastic structures at the beginning of the 9th century.[20]

Cistercians

There is evidence that in the late 13th century, the Cistercians would allow certain monks to perform their writing in a small cell "which could not... contain more than one person".[21] These cells were called scriptoria because of the copying done there, even though their primary function was not as a writing room.

Carthusians

The Carthusians viewed copying religious texts as their missionary work to the greater Church; the strict solitude of the Carthusian order necessitated that the manual labor of the monks be practiced within their individual cells, thus many monks engaged in the transcription of texts. In fact, each cell was equipped as a copy room, with parchment, quill, inkwell, and ruler. Guigues du Pin, or Guigo, the architect of the order, cautioned, "Let the brethren take care the books they receive from the cupboard do not get soiled with smoke or dirt; books are as it were the everlasting food of our souls; we wish them to be most carefully kept and most zealously made."[22]

The Orthodox church

The Resava

After the establishment of Manasija Monastery by Stefan Lazarević in the early 15th century, many educated monks have gathered there. They fostered copying and literary work that by its excellence and production changed the history of the South Slavic literature and languages spreading its influence all over the Orthodox Balkans. One of the most famous scholars of the so-called School of Resava was Constantine the Philosopher /Konstantin Filozof/, an influential writer and biographer of the founder of the school (Stefan Lazarević).

Rača

During the Turkish invasions of the Serbian lands (which lasted from the end of the 14th to the beginning of the 19th centuries) the monastery was an important centre of culture. The scriptorium of each monastery was a bastion of learning where illuminated manuscripts were being produced by monk-scribes, mostly Serbian liturgical books and Old Serbian Vita. hagiographies of kings and archbishops.

Numerous scribes of the Serbian Orthodox Church books—at the term of the 16th and the beginning of the 18th centuries—who worked in the Rača monastery are named in Serbian literature – "The Račans". . Among the monk-scribes the most renown are the illuminator Hieromonk Hristifor Račanin, Kiprijan Račanin, Jerotej Račanin, Teodor Račanin and Gavril Stefanović Venclović. These are well-known Serbian monks and writers that are the link between literary men and women of the late medieval (Late Middle Ages) and Baroque periods in art, architecture and literature in particular.

Monastic rules

Cassiodorus' Institutes

Although it is not a monastic rule as such, Cassiodorus did write his Institutes as a teaching guide for the monks at Vivarium, the monastery he founded on his family's land in southern Italy. A classically educated Roman convert, Cassiodorus wrote extensively on scribal practices. He cautions over-zealous scribes to check their copies against ancient, trustworthy exemplars and to take care not to change the inspired words of scripture because of grammatical or stylistic concerns. He declared "every work of the Lord written by the scribe is a wound inflicted on Satan", for "by reading the Divine Scripture he wholesomely instructs his own mind and by copying the precepts of the Lord he spreads them far and wide".[23] It is important to note that Cassiodorus did include the classical texts of ancient Rome and Greece in the monastic library. This was probably because of his upbringing, but was, nonetheless, unusual for a monastery of the time. When his monks copied these texts, Cassiodorus encouraged them to amend texts for both grammar and style.[24]

Saint Benedict

The more famous monastic treatise of the 7th century, Saint Benedict of Nursia's Rule, fails to mention the labor of transcription by name, though his institution, the monastery of Montecassino, developed one of the most influential scriptoria, at its acme in the 11th century, which made the abbey "the greatest center of book production in South Italy in the High Middle Ages".[25] Here was developed and perfected the characteristic "Cassinese" Beneventan script under Abbot Desiderius.

The Rule of Saint Benedict does explicitly call for monks to have ready access to books during two hours of compulsory daily reading and during Lent, when each monk is to read a book in its entirety.[26] Thus each monastery was to have its own extensive collection of books, to be housed either in armarium (book chests) or a more traditional library. However, because the only way to obtain a large quantity of books in the Middle Ages was to copy them, in practice this meant that the monastery had to have a way to transcribe texts in other collections.[27] An alternative translation of Benedict's strict guidelines for the oratory as a place for silent, reverent prayer actually hints at the existence of a scriptorium. In Chapter 52 of his Rule, Benedict's warns: "Let the oratory be what it is called, and let nothing else be done or stored there".[28] But condatur translates both as stored and to compose or write, thus leaving the question of Benedict's intentions for manuscript production ambiguous.[29] The earliest commentaries on the Rule of Saint Benedict describe the labor of transcription as the common occupation of the community, so it is also possible that Benedict failed to mention the scriptorium by name because of the integral role it played within the monastery.

Saint Ferréol

Monastic life in the Middle Ages was strictly centered around prayer and manual labor. In the early Middle Ages, there were many attempts to set out an organization and routine for monastic life. Montalembert cites one such sixth-century document, the Rule of Saint Ferréol, as prescribing that "He who does not turn up the earth with the plough ought to write the parchment with his fingers."[30] As this implies, the labor required of a scribe was comparable to the exertion of agriculture and other outdoor work. Another of Montalembert's examples is of a scribal note along these lines: "He who does not know how to write imagines it to be no labour, but although these fingers only hold the pen, the whole body grows weary."[31]

Cistercians

An undated Cistercian ordinance, ranging in date from 1119–52 (Załuska 1989) prescribed literae unius coloris et non depictae ("letters of one color and not ornamented"), that spread with varying degrees of literalness in parallel with the Cistercian order itself, through the priories of Burgundy and beyond.

In 1134, the Cistercian order declared that the monks were to keep silent in the scriptorium as they should in the cloister.

Books and transcription in monastic life

Manuscript-writing was a laborious process in an ill-lit environment that could damage one's health. One prior complained in the tenth century:

"Only try to do it yourself and you will learn how arduous is the writer's task. It dims your eyes, makes your back ache, and knits your chest and belly together. It is a terrible ordeal for the whole body".[32]

The director of a monastic scriptorium would be the armarius ("provisioner"), who provided the scribes with their materials and supervised the copying process. However, the armarius had other duties as well. At the beginning of Lent, the armarius was responsible for making sure that all of the monks received books to read,[26] but he also had the ability to deny access to a particular book. By the 10th century the armarius had specific liturgical duties as well, including singing the eighth responsory, holding the lantern aloft when the abbot read, and approving all material to be read aloud in church, chapter, and refectory.[33]

While at Vivarium c. 540–548, Cassiodorus wrote a commentary on the Psalms entitled Expositio Psalmorum as an introduction to the Psalms for individuals seeking to enter the monastic community. The work had a broad appeal outside of Cassiodorus' monastery as the subject of monastic study and reflection.

Abbot Johannes Trithemius of Sponheim wrote a letter, De Laude Scriptorum (In Praise of Scribes), to Gerlach, Abbot of Deutz in 1492 to describe for monks the merits of copying texts. Trithemius contends that the copying of texts is central to the model of monastic education, arguing that transcription enables the monk to more deeply contemplate and come to a more full understanding of the text. He then continues to praise scribes by saying "The dedicated scribe, the object of our treatise, will never fail to praise God, give pleasure to angels, strengthen the just, convert sinners, commend the humble, confirm the good, confound the proud and rebuke the stubborn".[34] Among the reasons he gives for continuing to copy manuscripts by hand, are the historical precedent of the ancient scribes and the supremacy of transcription to all other manual labor. This description of monastic writing is especially important because it was written after the first printing presses came into popular use. Trithemius addresses the competing technology when he writes, "The printed book is made of paper and, like paper, will quickly disappear. But the scribe working with parchment ensures lasting remembrance for himself and for his text".[34] Trithemius also believes that there are works that are not being printed but are worth being copied.[35]

In his comparison of modern and medieval scholarship, James J. O'Donnell describes monastic study in this way:

"[E]ach Psalm would have to be recited at least once a week all through the period of study. In turn, each Psalm studied separately would have to be read slowly and prayerfully, then gone through with the text in one hand (or preferably committed to memory) and the commentary in the other; the process of study would have to continue until virtually everything in the commentary has been absorbed by the student and mnemonically keyed to the individual verses of scripture, so that when the verses are recited again the whole phalanx of Cassiodorian erudition springs up in support of the content of the sacred text".[36]

In this way, the monks of the Middle Ages came to intimately know and experience the texts that they copied. The act of transcription became an act of meditation and prayer, not a simple replication of letters.

See also

- Phenomena

- Names

- Category

- Books by century

References

- "scriptorium". Dictionary.com Unabridged. Random House. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- "Scriptorium", "Encyclopedia Britannica"

- De Hamel, 1992, p. 36

- Barbara A. Shailor, The Medieval Book, (Toronto: U Toronto Press, 1991), p. 68.

- cf. Aliza Muslin-Cohen, A Medieval Scriptorium: St. maria Magdalena de Frankenthal series Wolfenbüttler Mittelalter Studien (Wiesbaden) 1990.

- McKitterick, 1996

- De Hamel, 1992, p. 5

- for example, cf. De Hamel, 1992, p. 5

- "Old St. Paul's Cathedral" William Benham, 1902. (gutenberg.org). Plate 24. Please also note Sloane Mss 2468

- "Library or labyrinth" Irene O’Daly. January 11, 2013 (medievalfragments.wordpress.com)

- "Pondering the physical scriptorium" Jenneka Janzen. January 25, 2013 by medievalfragments (medievalfragments.wordpress.com)

-

Du Cange, et al., Glossarium mediae et infimae Latinitatis, Niort: L. Favre, 1883–1887 (10 vol.).

Scriptorium, see also

Celenza, Christopher S. (Spring 2004). "Creating Canons in Fifteenth-Century Ferrara: Angelo Decembrio's "De politia litteraria," 1.10". Renaissance Quarterly. The University of Chicago Press. 57 (1): 43–98. JSTOR 1262374.

Since the early medieval days of the foundling monastic orders, the library and the scriptorium had been linked. for the most part, the library was a storage space. Reading was done elsewhere.

- Janet Charlotte Smith, "The Side Chambers of San Giovanni Evangelista in Ravenna: Church Libraries of the Fifth Century" Gesta, 29.1 (1990): 86–97)

- E. Mackowiecka, The Origin and the Evolution of the Architectural Forms of the Roman Library (Warsaw) 1978, noted by Smith 1990.

- Optic, Oliver (February 15, 1868). "Perpetual Lamps". Our Boys and Girls. 3 (59): 112. Retrieved 22 January 2019.

- Norman, Jeremy. "The Scriptorium and Library at the Vivarium (Circa 560)". HistoryofInformation.com. Jeremy Norman & Co., Inc. Retrieved 29 September 2014.

- Martyn, Lyons (2011). Books : a living history. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum. ISBN 9781606060834. OCLC 707023033.

- Rule of Saint Benedict, Chapter 57, Kansasmonks.org, accessed 2 May 2007.

- Fr. Landelin Robling OSB, Monastic Scriptoria, OSB.org, accessed 2 May 2007.

- A.C. Murray, After Rome's Fall, (Toronto: University Toronto Press, 1998), pp. 262, 283.

- George Haven Putnam, Books and their Makers During the Middle Ages, (New York: Hillary House, 1962), 405.

- C.H.Lawrence, Medieval Monasticism, Ed.2 (London & New York: Longman, 1989) 162.

- Cassiodorus, Institutes, I, xxx

- James O. O'Donnell, Cassiodorus, University of Californian Press, 1979. Postprint online (1995), Upenn.edu, accessed 2 May 2007.

- Newton 1999:3; the scriptorium is fully examined in Francis Newton, The Scriptorium and Library at Monte Cassino, 1058–1105, 1999.

- Rule of Saint Benedict, Chapter 48, Kansasmonks.org, accessed 2 May 2007.

- Geo. Haven Putnam, Books and Their Makers During the Middle Ages, (New York: Hillary House, 1962), p. 29.

- Rule of Saint Benedict, Chapter 52, Kansasmonks.org, accessed 2 May 2007.

- Fr. Landelin Robling OSB, Monastic Scriptoria, OSB.org, accessed 2 May 2007.

- Montalembert, The Monks of the West from St. Benedict to St. Bernard, vol. 6, (Edinburgh, 1861–1879) p. 191.

- Montalembert, The Monks of the West from St. Benedict to St. Bernard, vol. 6, (Edinburgh, 1861–1879) p. 194.

- Quoted in: Greer, Germaine. The Obstacle Race: The Fortunes of Women Painters and Their Work. Tauris Parke, 2001. p. 155.

- Fassler, Margot E., "The Office of the Cantor in Early Western Monastic Rules and Customaries," in Early Music History, 5 (1985), pp. 35, 40, 42.

- Johannes Trithemius, In Praise of Scribes (de Laude Scriptorum), Klaus Arnold, ed. (Lawrence, Kansas: Colorado Press, 1974), p. 35.

- Johannes Trithemius, In Praise of Scribes (de Laude Scriptorum), Klaus Arnold, ed. (Lawrence, Kansas: Colorado Press, 1974), p. 65.

- O'Donnell, James O. (1979). "Cassiodorus". University of California Press. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

Sources

- De Hamel, Christopher (1992). Scribes and illuminators (Repr. ed.). Univ. of Toronto Press. ISBN 0802077072.

- McKitterick, Rosamond (1 March 1990), "Carolingian Book Production: Some Problems", The Library: 1–33, doi:10.1093/library/s6-12.1.1

Further reading

- Alexander, J. J. G. Medieval Illuminators and Their Methods of Work. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992.

- Bischoff, Bernard, "Manuscripts in the Age of Charlemagne," in Manuscripts and Libraries in the Age of Charlemagne, trans. Gorman, pp. 20–55. Surveys regional scriptoria in the early Middle Ages.

- Diringer, David. The Book Before Printing: Ancient, Medieval and Oriental. New York: Dover, 1982.

- Lawrence, C.H. Medieval Monasticism: Forms of Religious Life in Western Europe in the Middle Ages, Ed. 2. London: Longman, 1989.

- Maitland, Samuel Roffey. The Dark Ages. London : J.G.F. & J.Rivington, 1844. Archive.org

- McKitterick, Rosamond. "The Scriptoria of Merovingian Gaul: a survey of the evidence." In Books, Scribes and Learning in the Frankish Kingdoms, 6th–9th Centuries, VII 1–35. Great Yarmouth: Gilliard, 1994. Originally published in H.B. Clarke and Mary Brennan, trans., Columbanus and Merovingian Monasticism, (Oxford: BAR International Serries 113, 1981).

- McKitterick, Rosamond. "Nun's scriptoria in England and Francia in the eighth century". In Books, Scribes and Learning in the Frankish Kingdoms, 6th-9th Centuries, VII 1–35. Great Yarmouth: Gilliard, 1994. Originally published in Francia 19/1, (Sigmaringen: Jan Thornbecke Verlag, 1989).

- Nees, Lawrence. Early Medieval Art. Oxford: Oxford U Press, 2002.

- Shailor, Barbara A. The Medieval Book. Toronto: U Toronto Press, 1991.

- Sullivan, Richard. "What Was Carolingian Monasticism? The Plan of St Gall and the History of Monasticism." In After Romes's Fall: Narrators and Sources of Early Medieval History, edited by Alexander Callander Murray, 251–87. Toronto: U of Toronto Press, 1998.

- Vogue, Adalbert de. The Rule of Saint Benedict: A Doctrinal and Spiritual Commentary. Kalamazoo: Cistercian, 1983.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Scriptorium. |