Reston, Virginia

Reston is a census-designated place in Fairfax County, Virginia. Founded in 1964, Reston was influenced by the Garden City movement that emphasized planned, self-contained communities that intermingled green space, residential neighborhoods, and commercial development.[4] The intent of Reston's founder, Robert E. Simon, was to build a town that would revolutionize post–World War II concepts of land use and residential/corporate development in suburban America.[5] In 2018, Reston was ranked as the Best Place to Live in Virginia by Money magazine for its expanses of parks, lakes, golf courses, and bridle paths as well as the numerous shopping and dining opportunities in Reston Town Center.[6]

Reston, Virginia | |

|---|---|

| |

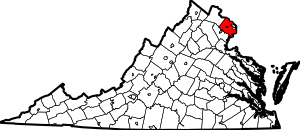

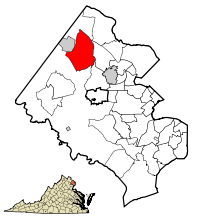

Location of Reston in Fairfax County, Virginia | |

Reston, Virginia Location of Reston in Fairfax County, Virginia  Reston, Virginia Reston, Virginia (Virginia)  Reston, Virginia Reston, Virginia (the United States) | |

| Coordinates: 38°57′16″N 77°20′47″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Virginia |

| County | Fairfax |

| Founded | April 10, 1964 |

| Founded by | Robert E. Simon |

| Area | |

| • Total | 15.7 sq mi (40.6 km2) |

| • Land | 15.3 sq mi (39.7 km2) |

| • Water | 0.3 sq mi (0.9 km2) |

| Elevation | 360 ft (110 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 58,404 |

| • Estimate (2018) | 60,335 |

| • Density | 3,700/sq mi (1,400/km2) |

| Demonym(s) | Restonian |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 20190, 20191, 20194 |

| Area code(s) | 703, 571 |

| FIPS code | 51-66672[2] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1499951[3] |

| Website | www |

The U.S. Census Bureau estimated Reston's population to be 60,070 as of December 2017.[7]

History

In the early days of Colonial America, the land on which Reston sits was part of the Northern Neck Proprietary, a vast grant by King Charles II to Lord Thomas Fairfax that extended from the Potomac River to the Rappahannock. The property remained in the Fairfax family until they sold it in 1852.[8]

Carl A. Wiehle and William Dunn bought 6,449 acres in northern Fairfax County along the Washington & Old Dominion (W&OD) Railroad line in 1886, later dividing the land between them, with Wiehle retaining the acreage north of the railroad line. Wiehle envisioned founding a town on the property, including a hotel, parks, and community center, but completed only a handful of homes before his death in 1901.[8]

Wiehle's heirs eventually sold the land, which changed hands several times before being purchased by the A. Smith Bowman family, who built a bourbon distillery on the site. By 1947, the Bowmans had acquired the former Dunn tract south of the railroad, for total holdings of over 7,000 acres. In 1961, Robert E. Simon used funds from his family's recent sale of Carnegie Hall to buy most of the land, except for 60 acres (240,000 m2) on which the Bowman distillery continued to operate until 1987.[8][9]

Conception and guiding principles

Simon officially launched Reston on April 10, 1964 (his 50th birthday) and named the community using his initials.[7] He laid out seven "guiding principles" that would stress quality of life and serve as the foundation for its future development. His goal was for Restonians to live, work, and play in their own community, with common grounds and scenic beauty shared equally regardless of income level, thereby building a stronger sense of community ties.[5] The initial motto of the community, as articulated by Simon, was "Work, Play, Live"[10] (or, as more often was memorialized onto Reston merchandise, "Live, Work, Play.")

Simon's seven principles are:

- The town should provide a variety of leisure opportunities, including a wide range of cultural and recreational facilities as well as an environment for privacy;

- Residents would be able to remain in the community throughout their lives, with a range of housing meeting a variety of needs and incomes;

- The focal point of all planning would be on the importance and dignity of the individual and would take precedence for large-scale concepts;

- Reston residents would be able to live and work in the same community;

- Commercial, cultural, and recreational facilities would be available to residents immediately, not years later;

- Beauty, both structural and natural, is a necessity and should be fostered; and

- Reston should be a financial success.[8][11]

Simon envisioned Reston as a model for clustered residential development,[12] also known as conservation development, which puts a premium on the preservation of open space, landscapes, and wildlife habitats. Indeed, Reston was the first 20th-century private community in the U.S. to explicitly incorporate natural preservation in its planning (Greenbelt, Maryland, was a publicly supported community).[13]

Early years (1964–1967)

Simon hired the architectural firm of Whittlesey, Conklin, & Rossant to design his new community.[14][15] The plans for Reston were designed by architect James Rossant, who studied under Walter Gropius at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, and his partner William J Conklin. From the outset, Rossant and Conklin's planning conceptualized the new community as a unified, cohesive, and balanced whole, including landscapes, recreational, cultural, and commercial facilities, and housing for what was envisioned to be a town of 75,000.[16] For Lake Anne Plaza, the first of Reston's village centers, the architects combined a small shopping area with a mix of single-family houses, townhouses, and apartments next to a manmade lake featuring a large jet fountain. Close by were the cubist townhouses at Hickory Cluster, designed by noted modernist architect Charles M. Goodman in the International Style. Lake Anne also included an elementary school, a gasoline station, and two churches as well as an art gallery and several restaurants. The first section of a senior citizens' residence facility, the Lake Anne Fellowship House, was completed several years later.

Reston welcomed its first residents in late 1964. During the community's first year, its continued development was covered in such major media publications as Newsweek, Time, Life Magazine, and the New York Times, which featured the new town in a front-page article extolling it as "one of the most striking communities" in the United States.[17]

Gulf Reston (1967–1978)

From early in Reston's conception and development, Robert Simon ran into financial difficulties as sales in the new community flagged. To keep his project going, he accepted a loan of $15 million from Gulf Oil that allowed him to pay off his creditors.[18] Even so, sales were sluggish as Simon's reluctance to compromise on his high standards for building designs and materials meant that a townhouse in Reston could cost as much as a single-family house elsewhere in Fairfax County.

By 1967, Gulf Oil forced Simon out and formed Gulf Reston, Inc., to manage the community. Gulf retained many of Simon's employees and continued to adhere largely to the spirit of the original Reston master plan as envisioned by Simon. During the 1970s, Gulf built the Reston International Center near the intersection of Sunrise Valley and Reston Parkway, and added low- to moderate-income housing to the community's residential mix, including the Cedar Ridge, Laurel Glade, and Fox Mill apartment developments. Gulf also constructed housing for employees of the U.S. Geological Survey headquarters, located on Sunrise Valley Drive.[18]

Most notably, Gulf Reston put a premium on protecting Reston's open spaces and pedestrian-friendly landscape throughout its ownership. The corporation also transferred title for many Reston recreational facilities, including land, parks, lakes, and facilities, to the Reston Homeowners Association, thereby preserving them from overdevelopment.[18]

Mobil Oil's Reston Land Corporation (1978–1996)

Within 10 years of buying Simon out, Gulf opted to begin pulling out of the real estate business and instead to focus exclusively on energy. It sold Reston's developed portions, including the three completed village centers (Lake Anne, Tall Oaks, and Hunters Woods), the Reston International Center, and Isaac Newton Square, to an investment firm. In 1978, the company finalized the sale of Reston's remaining 3,700 undeveloped acres to Mobil Oil, which pledged to continue respecting the ideals of Robert Simon. Mobil formed the Reston Land Corporation as a subsidiary to manage its holdings and began developing the remaining residential areas in what would become the South Lakes and North Point villages. Reston Land introduced a wider mix of housing choices, including more townhouses and smaller “starter” homes, and completed the North County Government Center, which houses the Reston District police station and Fairfax County government offices, as well as a regional library and homeless shelter.[18]

Reston Land also broke ground on the 460-acre Reston Town Center which formed part of Simon's original master plan for Reston. The first four-block development of this multi-phase mixed-use project were opened in 1996 and included a hotel, several restaurants, a cinema, and office buildings.[18]

Reston in the New Millennium (1996–present)

By 1996, Mobil had decided to follow Gulf Oil's steps and pull out of the land management business. It sold its entire Mobil Land Development subsidiary, including its Reston holdings, to Westbrook Partners, LLC, for $324 million.[19] As Reston Town Center continued to develop, Boston Properties emerged as a leading player. The company became the sole owner of the core mixed-use tracts in Reston Town Center when it completed the purchase of the Fountain Square office/retail complex in 2012.[20]

Planning and zoning

Reston is divided into three separate planning areas: the original Planned Residential Community (PRC) area that governs the majority of residential areas in the community; the Reston Town Center (RTC) District, which includes all of the high-density, high-rise portions of Town Center; and the Transit Station Area (TSA) on either side of the Dulles Toll Road.[21]

Planned Residential Community (PRC)

From Reston's inception, planning and zoning in the PRC area has emphasized the inclusion and integration of common grounds, parks, large swaths of wooded areas with picturesque runs (streams), wildflower meadows, golf courses, public swimming pools, bridle paths, a bike path, four lakes, tennis courts, and extensive foot pathways.[22] Reston was built in wooded areas of oak, maple, sycamore, and Virginia pine, and remains heavily wooded. Extensive canopy guidance protects tree cover throughout the PRC, and homeowners are prohibited from removing trees larger than 4 inches in diameter without written permission from Reston's Design Review Board.[23] Total zoning density throughout the overall PRC area is currently capped at 13 persons per acre.[21] This figure, however, does not include residents in Fairfax County workforce and affordable units (WDUs/ADUs), as well as the "bonus" units developers are allowed to add to their projects in compensation for having included ADUs in their proposals,[21]

.jpg)

Reston's five village centers are included in the PRC area. Simon envisioned a total of seven village centers, but only five were developed.[8][24] The village centers and the town center are an important part of Reston. Each village center, all of which (save North Point) predate the Reston Town Center, was intended to be a short walk from most homes and incorporate the daily retail and community service needs of residents. Moderately denser developments, such as apartments and townhouse clusters, as well as some single-family homes, encircle each center. The first to be built was the critically acclaimed Lake Anne, followed by (in chronological order) Hunters Woods, Tall Oaks, South Lakes, and North Point.[13] By 2015, however, Tall Oaks had become defunct as a village center and was purchased by a local development firm, Tall Oaks Development Company, with the intent of rezoning the 7.6-acre parcel and converting it to residential housing.[25]

Reston Town Center District (RTCD)

During Mobil's ownership period, the corporation worked with Fairfax County to create a new Town Center District to govern planning and design for existing and new development in the core Town Center area and to remove it from the oversight of Reston Association's Design Review Board.[26] Review and comment of all RTCD development proposals is limited to members of the RTC District Association, which is overseen by the 9-member Board of Directors, 7 of whom represent commercial property owners.[27]

Transit Station Area (TSA)

The core portion of the Transit Station Area (TSA)—consisting of the 12-lane Dulles Toll Road, Metro's heavy rail line, and the office parks on either side—cuts a half-mile wide swath through the community, with four north-south connections. A fifth crossover at Soapstone Drive has been proposed by Fairfax County transportation planners, though funding has not yet been identified.[28] Zoning and planning for TSA development is governed by Fairfax County; as with the RTC District, no direct oversight from Reston Association is included, while input from and notification to PRC residents is limited.[21] TSA zoning guidance explicits calls for this area to be designed as an urban center, with 30 million square feet of new and existing office development and 44,000 residential units.[21]

Accolades and coverage

The growth and development of Reston has been monitored by newspaper articles, national magazines, and scholarly journals on architecture and land use. In 1967 the First Lady of the United States, Mrs. Lyndon Johnson, visited Reston to take a walking tour along its pathways as part of her interest in beautification projects. Apollo 11 astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin visited Reston elementary schools named for them. The Washington Post featured a road trip to Reston in January 2006,[13] and a relatively new website "Beyond DC" has a page devoted to Reston with almost 150 photos.

Reston and Robert Simon were recognized by the American Institute of Certified Planners for their significant contributions to town planning. The AICP further recognized Reston as a National Planning Landmark, praising Simon's vision for ensuring that fields and trees would be threaded throughout the residential and commercial portions of the community, and recognized it as "one of the finest examples of American 20th century conceptual new town planning."[29]

In 2017, the Lake Anne Village Center's historic district was named to the U.S. Park Service's National Register of Historic Places, which serves as the official list of historic places worthy of preservation and protection.[30][31]

Reston is one of just a handful of communities in the U.S. that has been designated a Backyard Wildlife Habitat community.

Reston generally follows "new urbanism" guidelines.[32] The residential portion of the town was built with an extensive path system, and Fairfax County has constructed many sidewalks over the past decades.[33] The downtown and original areas also incorporate mixed-use development, with more mixed-use development planned near Washington Metro stations.[34]

However, Reston differs from New Urbanism principles in several important ways. Many buildings in the PRC area are oriented away from main streets, and several major arteries lack complete sidewalk networks as a result of Fairfax County's control over Reston's transportation planning: until recently, the Fairfax County zoning code only required developers to build sidewalks in certain limited cases. The original inward orientation of the village centers was an intentional design element by Reston's early planners, who wished to avoid the commercial strip look that dominates many suburban developments.[13]

Recreational and cultural activities

A special tax district within Fairfax County was created to fund various recreational, educational, and cultural activities in Reston. The Reston Community Center (RCC) is a core element,[35] with its main building in south Reston at Hunters Woods Plaza and featuring a theater, indoor heated swimming pool with jacuzzi, ballroom, meeting rooms, and classroom space. A smaller RCC branch is at Lake Anne Plaza.[36]

Parks and recreation

Building on Robert Simon's emphasis on preserving green space and providing recreational opportunities, Reston features over 55 miles of walking and hiking paths for residents, with currently about 250 acres of woodlands and open space. Reston is noted for its tree canopy, which currently covers about half of Reston's total area. It is one of only 8 American localities to be a member of the worldwide Biophilic Cities Organization, which promotes the importance of protecting and promoting nature within urban areas.[37][38]

The centerpiece of Reston's focus on nature is the Vernon J. Walker Nature Education Center. The Nature Center's 72 acres (290,000 m2) of hardwood forest include a picnic pavilion, campfire ring, and other facilities that support its outreach programs. Its LEED gold-certified Nature House offers exhibits, an on-site naturalist, and various programs for children; it may also be rented for community or private meetings.[39]

Two golf courses are located in Reston. The 166-acre Reston National Golf Course in south Reston is certified by Audubon International as a Cooperative Cooperative Sanctuary on the Chesapeake Bay watershed. The Hidden Creek Country Club was purchased in 2017 by Wheelock Communities, a real estate development company.[40]

The Washington and Old Dominion (W&OD) trail, which runs through Reston, is a 45-mile-long (72 km) pathway built solely for pedestrian and bicycle traffic along the former W&OD train line.

Reston contains four manmade lakes: Lake Anne, Lake Audubon, Lake Newport, and Lake Thoreau. Also within Reston's area is the 476-acre (1.9 km2) Lake Fairfax Park, operated by Fairfax County and which features boat rentals, a large outdoor pool complex called "The Water Mine", overnight campground facilities, and picnic areas.[41]

The 30-acre (120,000 m2) Roer's Safari is located on the northeast edge of the community.[42][43] It is dedicated to family-friendly animal interaction with bus rides and feeding stations. Animals include zebras, antelope, bison, cheetah, emu, giraffe, camels, goats, reptiles, and waterfowl.[44]

Reston has an assortment of pools, including a year-round indoor pool at the Reston Community Center.[45] Ice skating is available both year-round at SkateQuest, a privately run indoor rink, as well as at an outdoor rink that is open in winter only at Reston Town Center.[46][47]

Performing arts, galleries, & museums

Reston is home to several performing arts groups. The Reston Community Players (originally known as Reston Players) has been in operation since 1966 and performs at Reston Community Center's Center Stage in Hunters Woods Plaza.[48] The Reston Chorale was founded in the late 1960s as a mixed-voice chorus comprising both professional and amateur singers.[49] The Reston Community Orchestra, launched in 1988, also offers regular performances throughout the year, generally at the Reston Community Center.[50] In the summer, free public concerts are offered at both Reston Town Center[51] and at Lake Anne Plaza.[52]

The Greater Reston Arts Center (GRACE), founded by local artists, is home-based at Reston Town Center and sponsors the annual Northern Virginia Fine Arts Festival.[53] The privately owned Reston Art Gallery at Lake Anne Plaza includes both regular art exhibits and artist studio spaces.[54]

Reston's sole museum, the Reston Historic Trust & Museum, is also located in Lake Anne Plaza. It has maps, photos, and books that provide a detailed look at Reston from the 1960s on.[55]

The Washington West Film Festival is an autumn event in Reston center. The festival, co-founded by Mark Maxey and Brad Russell, offers a juried array of feature films, shorts and documentaries.[56][57][58]

Annual calendar of events

- Northern Virginia Fine Arts Festival (Reston Town Center) (May)

- Taste of Reston Food Festival (Reston Town Center) (June)

- Reston Triathlon (September)

- Reston Multicultural Festival (Lake Anne Plaza) (late September)

- Flavors of Fall (Reston Town Center) (October)

- Reston Holiday Parade (Reston Town Center) (November)

Economy

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, "professional, scientific, and technical services" are by far the largest economic activity in Reston, consisting of 757 different companies employing 21,575 people in 2007.[59] The Information sector[60] follows second with 9,876 employees working at 150 companies in Reston. Reston is part of the Dulles Technology Corridor and is home to Carahsoft, Comscore, Leidos, Maximus, Rolls-Royce North America, Science Applications International Corporation, NII, NVR, Noblis, Verisign, and Learning Tree International. In addition, the United States Geological Survey, National Wildlife Federation, American College of Radiology, and CNRI are homebased in Reston. Google Federal Services and Gate Group's North American division offices also are in Reston.[61][62] In 2019, General Dynamics moved its corporate headquarters to Reston.[63]

Of the 20 largest venture capital firms in the D.C. area, five are in Reston. The amount of capital under management of the Reston firms, $6.9 billion, represents 53% of those top 20 regional venture capital firms.[64]

Reston also serves as the headquarters for the North American command of the German armed forces which oversees upwards up 1,500 troops deployed in the United States at any given time.[65]

Transportation

_and_the_Silver_Line_of_the_Washington_Metro_from_the_overpass_for_Virginia_State_Route_286_(Fairfax_County_Parkway)_in_Reston%2C_Fairfax_County%2C_Virginia.jpg)

Reston sits astride the Dulles Toll Road, 10 miles from Tysons Corner and the Capital Beltway to the east, and 6 miles (10 km) from Washington Dulles International Airport to the west. Four roads cross the community from north to south: Fairfax County Parkway on the western side, Reston Parkway through the center of town, Wiehle Avenue through the northeastern residential section, and Hunter Mill Road on the eastern border.[66]

The Metro's Silver Line, which runs along the Dulles Toll Road, opened its first Reston station, Wiehle-Reston East, on July 26, 2014. Two additional stations, Reston Town Center and Herndon, should open in early 2021 to serve the western half of Reston. They are working towards building out the metro to Dulles International Airport.[67]

The Reston Internal Bus System (RIBS) provides five regularly circulating routes connecting Reston's village centers, using Reston Town Center as a hub.[68][69] Fairfax County's Fairfax Connector and Metrobus service both link commuters in Reston to Metro stations as well as points throughout Fairfax County.

Geography

Reston is located in northern Fairfax County at 38°57′16″N 77°20′47″W.[70] Neighboring communities are Great Falls to the north, Wolf Trap to the east, Franklin Farm, Floris, and McNair to the southwest, the town of Herndon to the west, and Dranesville to the northwest.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the Reston CDP has a total area of 15.7 square miles (40.6 km2), of which 15.3 square miles (39.7 km2) is land and 0.35 square miles (0.9 km2), or 2.10%, is water.[71]

Climate

The climate in this area is characterized by hot, humid summers and generally mild to cool winters. According to the Köppen Climate Classification system, Reston has a humid subtropical climate, abbreviated "Cfa" on climate maps.[72]

| Climate data for Reston, Virginia | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 75 (24) |

79 (26) |

89 (32) |

93 (34) |

97 (36) |

100 (38) |

104 (40) |

104 (40) |

99 (37) |

94 (34) |

84 (29) |

79 (26) |

104 (40) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 41.4 (5.2) |

44.6 (7.0) |

54.9 (12.7) |

66 (19) |

74.6 (23.7) |

83 (28) |

87.2 (30.7) |

86.0 (30.0) |

79 (26) |

67.6 (19.8) |

56.8 (13.8) |

45.3 (7.4) |

65.5 (18.6) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 22.8 (−5.1) |

24.3 (−4.3) |

32.4 (0.2) |

41.3 (5.2) |

50.7 (10.4) |

60 (16) |

64.9 (18.3) |

63.6 (17.6) |

56 (13) |

43.1 (6.2) |

34.7 (1.5) |

26.5 (−3.1) |

43.4 (6.3) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −18 (−28) |

−14 (−26) |

−1 (−18) |

17 (−8) |

28 (−2) |

36 (2) |

41 (5) |

38 (3) |

30 (−1) |

15 (−9) |

9 (−13) |

−4 (−20) |

−18 (−28) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.8 (71) |

2.7 (69) |

3.4 (86) |

3.2 (81) |

4.2 (110) |

4.2 (110) |

3.6 (91) |

3.7 (94) |

3.8 (97) |

3.2 (81) |

3.3 (84) |

3.2 (81) |

41.3 (1,055) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 7.1 (18) |

7.5 (19) |

3.1 (7.9) |

0.3 (0.76) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

trace | 0.8 (2.0) |

4 (10) |

22.8 (57.66) |

| Average precipitation days | 10 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 12 | 11 | 11 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 117 |

| Average snowy days | 4 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 11 |

| Source: Weatherbase[73] | |||||||||||||

Education

Primary and secondary schools

As a part of Fairfax County, Reston is served by Fairfax County Public Schools and a number of private schools. Reston has one high school within its boundaries, South Lakes High School, which serves most of Reston.[74] Adjacent to South Lakes High School is Reston's only middle school, Langston Hughes Middle School. Students who live in the far northern part of Reston attend Herndon High School.[75]

Public elementary schools:

- Buzz Aldrin Elementary School

- Neil Armstrong Elementary School

- A. Scott Crossfield Elementary School

- Dogwood Elementary School

- Forest Edge Elementary School

- Fox Mill Elementary School

- Hunters Woods Elementary School for the Arts and Sciences

- Lake Anne Elementary School

- Sunrise Valley Elementary School

- Terraset Elementary School

Private schools:

- Children's House Montessori School of Reston

- Community Montessori School

- Reston Montessori School

- Academy of Christian Education (elementary)

- Edlin (elementary and middle school)[76]

- United Christian Parish Preschool

- Lake Anne Nursery and Kindergarten (LANK)

- Ideaventions Academy for Math and Science (4th - 12th)

- Reston Children's Center (RCC)

Colleges and universities

Reston has several higher education resources, including a satellite campus of NVCC (Northern Virginia Community College), the University of Phoenix – Northern Virginia campus, and Marymount University – Reston Center.

Public libraries

Fairfax County Public Library operates the Reston Regional Library.[77][78] Also located in Reston is the United States Geological Survey Library, a federal research library that is open to the public with over 3 million items, ranging from books and journals to maps and photographs, as well as field record notebooks.

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1970 | 5,722 | — | |

| 1980 | 36,407 | 536.3% | |

| 1990 | 48,556 | 33.4% | |

| 2000 | 56,407 | 16.2% | |

| 2010 | 58,404 | 3.5% | |

| Est. 2018 | 60,335 | 3.3% | |

| 2018 5-Year Estimate[1] | |||

As of the census[79] of 2000, there were 56,407 people, 23,320 households, and 14,481 families residing in the CDP, with a population density of 3,288.6 people per square mile (1,269.9/km²). There were 24,210 housing units at an average density of 1,411.5/sq mi (545.0/km²). Reston's racial composition was 73.62% White, 9.12% African American, 0.25% Native American, 9.62% Asian, 0.04% Pacific Islander, 4.12% from other races, and 3.23% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 10.10% of the population.

There were 23,320 households out of which 29.6% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 50.2% were married couples living together, 8.9% had a female householder with no husband present, and 37.9% were non-families. 29.3% of all households were made up of individuals and 5.2% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.40 and the average family size was 2.99.

Reston's population has a median age of 36 years.

The median income for a household was $80,018, and the median income for a family was $94,061 (as of a 2007 estimate, these figures had risen to $93,417 and $130,221, respectively[80]). The per capita income was $42,747. About 3.2% of families and 4.5% of the population were below the poverty line, including 6.1% of those under age 18 and 7.0% of those age 65 or over.

Reston has a high proportion of college-educated adults, with 66.7% having completed at least some college.[81]

Governance

Reston is an unincorporated area in Fairfax County; its schools, roads, and law enforcement services are provided by Fairfax County.[82]

Parks, recreation facilities, and common grounds, as well as the extensive trail system, are overseen by the Reston Association under the provisions of the Reston Deed, the community's basic governing document. A standard assessment is levied on each apartment or lot (for townhouses and houses). The Deed also allows for reduced assessments for those who "qualify for real estate tax reduction by Fairfax County Ordinance; (ii) their units are subsidized by the federal or state government; or (iii) their units are designed and used primarily for elderly congregate care or assisted living facilities and occupied by low or moderate income residents."[83]

Reston's individual clusters or neighborhoods have their own neighborhood associations which also levy assessments to cover grounds upkeep, snow removal, trash pick-up, and other maintenance. Each cluster has its own elected board of directors who report to the residents of that cluster.

The majority of Reston lies within Virginia's 11th congressional district and is currently represented in Congress by Representative Gerry Connolly (D).[84] A portion of Reston is in Virginia's 10th District and is represented by Congresswoman Jennifer Wexton (D). It is represented by Ken Plum (D) in the Virginia House of Delegates, and by Janet Howell (D) in the State Senate.

While Reston has, from its inception, been an unincorporated area, several efforts have been made to achieve town status, primarily to gain more control over zoning and development decisions, which now are the purview of Fairfax County elected officials and staff. Robert Simon initially explored the option of incorporation as a town but was blocked by Fairfax County. Simon asserted to an interviewer that Fairfax officials informed him they would deny Reston access to Fairfax's water and sewer lines if he sought incorporation for his new community. In 1980, a group of Reston residents were successful in pushing for a referendum to incorporate Reston as a town, but the referendum failed in 1980 by a 2–1 margin.[85] A similar initiative in 2005, which was publicly supported by Robert Simon, also failed.

Local media

Reston is served primarily by the Washington, D.C. media market. The community lies within the local distribution area for two national newspapers, the Washington Post and the Washington Times,[86][87] as well as two local publications, the Fairfax Times and the Reston Connection.[88] All four also offer digital subscriptions. A third local paper, the "Observer," which covered Reston and nearby Herndon, closed in 2010 and transferred coverage to AOL's Patch service of local digital news sites, which launched a Reston site in August 2010.[89] Website Reston Now provides daily local news coverage.[90] In addition, multiple television and radio stations in the Washington metropolitan area provide coverage of local developments.[91]

Notable events

Ebola virus scare

A filovirus, at first suspected to be Ebola virus (EBOV), was discovered among crab-eating macaques (Macaca fascicularis) within the Covance Primate Quarantine Unit in 1989. This attracted significant media attention, including the publication of The Hot Zone. The filovirus was found to be distinct from EBOV and to be nonpathogenic for humans. It was named after the community, and is now known as Reston virus (RESTV). Macaques found to be or suspected to be infected with RESTV were euthanized, and the facility was sterilized.[92] The facility was located in an office park near Sunset Hills Road and Wiehle Avenue. It was eventually torn down, and a daycare was built in its place.

Notable residents

Notable people who were born in and/or have lived in Reston include professional basketball player Grant Hill,[93] track and field athlete and Olympian Alan Webb, speed skating Olympian Maame Biney, mystery writer Donna Andrews, musician Roy Buchanan,[94] chess grandmaster Lubomir Kavalek and young pop singer and influencer Jacob Sartorius.

Notable local organizations

Publicly funded organizations:

- Reston Community Center (RCC)

Civic organizations:

- Reston Citizens Association (RCA)

- Cornerstones (formerly Reston Interfaith)

- U.S. Junior Chamber of Commerce (Reston Jaycees)

Community-based grass-roots organizations:

- Rescue Reston (opposes redevelopment of Reston National Golf Course, Hidden Creek Golf Course)

- Reclaim Reston (opposes high-density development of St. John's Woods, supports reclaiming Robert Simon's vision)

- Reston 20/20 (dedicated to sustaining Reston's quality of life through excellence in community planning, zoning, and development)

- Coalition for a Planned Reston (CPR) (coalition of RCA, Reclaim Reston, and Reston 20/20)[95]

Privately funded organizations:

- Reston Association (previously known as the Reston Home Owners Association, RHOA)

- ArtInsights Animation and Film Art Gallery

See also

- Northern Virginia

- Fairfax County

- Lake Anne

- Reston Station

- Wiehle–Reston East station

- Portofino

References

- "Reston CDP, Virginia". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 7, 2020.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- Tom Grubisich, “Reston, Virginia,” Encyclopedia of Virginia, https://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/Reston_Virginia#start_entry, accessed 6 May 2018

- "Reston Master Plan". Archived from the original on September 15, 2009. Retrieved February 28, 2009.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- Kerri Anne Renzulli and Sergei Khlebnikov, "This is the Best Place to Live in Every State," Money Magazine, January 26, 2018, http://time.com/money/5108196/best-places-to-live-every-state-us/, accessed May 6, 2018.

- "TownCharts, Reston, Virginia Demographics Data". TownCharts. Retrieved June 9, 2018.

- "A Brief History of Reston, Virginia," Gulf Reston, January 1970, George Mason Archival Repository Service, retrieved April 2018, http://mars.gmu.edu/handle/1920/1268?show=full

- "Itinerary Reston, Virginia". Archived from the original on November 27, 2006. Retrieved October 12, 2007.

- Verity. "Learning from Reston's 50 years of "Work, Play, Live"". www.veritycommercial.com. Retrieved December 12, 2018.

- "Reston@50: Planning, Designing and Marketing Reston". George Mason University archives. Retrieved May 15, 2018.

- "Model Residential Cluster Development Ordinance" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 27, 2007. Retrieved October 12, 2007.

- Sloan, Willona (January 29, 2006). "The Nature of Reston" (PDF). Washington Post. p. M08. Retrieved March 20, 2007.

- "Robert E. Simon, Jr./Reston, Virginia," Historical Marker Database, marker provided by the American Institute of Certified Planners, https://www.hmdb.org/marker.asp?marker=89538, accessed 15 May 2018.

- Elliott, J. Michael (May 23, 1995). ""Julian Whittlesey, Archeologist and architect"". New York Times. Retrieved May 15, 2018.

- Grimes, William (December 18, 2009). ""James Rossant, Architect and Planner, Dies at 81"". New York Times. Retrieved May 15, 2018.

- Huxtable, Ada Louise (December 5, 1965). ""Fully Planned Town Opens Virginia; The Totally Planned Community of Reston, Va., Is Dedicated With 'Salute to Arts'"". New York Times. Retrieved May 14, 2018.

- "Reston@50: Gulf and Mobil". George Mason University archives. Archived from the original on May 16, 2018. Retrieved May 15, 2018.

- "Mobil Sells Land Development Business to Westbrook". The Free Library. June 10, 1996. Retrieved May 15, 2018.

- Goff, Karen (October 30, 2015). "Boston Properties Makes Deal to be Reston Town Center's Sole Owner". Reston Now. Retrieved May 15, 2018.

- "Fairfax County Comprehensive Plan, 2017 Edition, Area III (Reston)" (PDF). Fairfax County Government. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- "Reston Paths". Retrieved March 20, 2007.

- "Proposed Rules Will Make It Tougher to Remove a Tree". Reston Now. June 18, 2015. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- Reston Village Centers, Reston Association, https://www.reston.org/AroundReston/RestonVillageCenters/tabid/155/Default.aspx, accessed 8 May 2018.

- "Sold: Tall Oaks Village Center". Reston Now. January 8, 2015. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- "Reston Town Center Design Guidelines and Review Process" (PDF). Reston Town Center Association. December 2005. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- "About Reston Town Center Association". Reston Town Center Association. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- "Northern Virginia Transportation Authority, 2018 Project List" (PDF). Retrieved May 17, 2018.

- "Robert E. Simon, Jr.,/Reston, Virginia". Historical Marker Database. 2002. Retrieved May 15, 2018.

- "National Register of Historic Places". National Park Service. 2017. Retrieved May 15, 2018.

- "Lake Anne Village Center Named Historic District" (PDF). Reston Connection. August 9, 2017. Retrieved May 15, 2018.

- "Reston, VA – New Town meets New Urbanism". Retrieved March 20, 2007.

- "Fairfax County Comprehensive Plan, 2003 Edition – Transportation, amended through 7-10-2006" (PDF). Fairfax County, VA. July 10, 2006. Retrieved March 20, 2007. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - MacGillis, Alec (February 16, 2006). "County Picks Project for Wiehle Avenue Site". Washington Post. p. VA03. Retrieved March 20, 2007.

- "Small District 5". Archived from the original on June 22, 2006. Retrieved October 12, 2007.

- "About Us". Reston Community Center. Archived from the original on September 2, 2007. Retrieved October 12, 2007.

- "Biophilic Cities Organization". Biophilic Cities. 2017. Retrieved May 15, 2018.

- "Reston Association Pathways". Retrieved November 19, 2008.

- "The Nature House". Reston Association. The Reston Association. Retrieved May 17, 2017.

- "Reston, Virginia Golf Courses". Retrieved October 12, 2007.

- "Lake Fairfax Park". Fairfax County Government. Retrieved October 12, 2007.

- "Reston CDP." United States Census Bureau. Retrieved on April 4, 2009.

- Home page. Reston Zoo. Retrieved on April 4, 2009.

- "Reston Zoo – A Petting Zoo in Vienna, Virginia". About.com. Retrieved October 12, 2007.

- Reston Community Center

- "SkateQuest". SkateQuest Ice Rink. Retrieved May 17, 2018.

- "Reston Town Center Amenities". Retrieved May 17, 2018.

- "Reston Community Players". Reston Community Players. Retrieved May 17, 2018.

- "Reston Chorale". Retrieved May 17, 2018.

- "Reston Community Orchestra".

- "Reston Town Center Summer Concert Series Includes Jazz, Rock, More". Reston Now. May 18, 2017. Retrieved May 17, 2018.

- "Lake Anne Living/Concerts". Lake Anne Plaza. Retrieved May 17, 2018.

- "Greater Reston Arts Center". Reston Arts. Retrieved May 17, 2018.

- "Reston Art Gallery & Studios". Reston Art Gallery. Retrieved May 17, 2018.

- "Reston Museum". Retrieved April 7, 2009.

- Valverde, Rochelle (July 6, 2015). "Lawrence native wins Emmy for excellence in TV production". Lawrence Journal-World.

- Merry, Stephanie (October 22, 2013). "A dash of Cannes in Middleburg and Reston film festivals". Washington Post.

- Fraley, Jason (October 23, 2018). "Washington West returns to Reston as Virginia's most charitable film festival". WTOP-FM. Retrieved May 13, 2019.

- "http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/GQRTable?_bm=y&-ds_name=EC0700A1&-geo_id=E6000US5105966672&-_lang=en Archived July 3, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved on January 21, 2011.

- "http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/MetadataBrowserServlet?type=codeRef&id=51&dsspName=ECN_2007&ibtype=NAICS2007&back=update&_lang=en%5B%5D. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved on January 21, 2011.

- "Google Offices." Google. Retrieved on July 12, 2009.

- "Contact Us." Gate Group. Retrieved on September 17, 2011. "North America Regional Office11710 Plaza America Drive, Suite 800 Reston, VA 20190 USA"

- Brown, David (September 9, 2019). "Air Force probes how it chooses accommodations after Scotland flap". POLITICO. Retrieved January 8, 2020.

- "Doing Business in Greater Washington Largest Venture Capital Funds". Greater Washington Initiative. 2007. Archived from the original on August 16, 2007. Retrieved October 12, 2007.

- "'Hiding' in Reston Since 1991: German armed forces command for North America is on Sunrise Valley Drive". connectionnewspapers.com. April 10, 2007. Retrieved March 6, 2017.

- Barrett, Randy; Jenks, Andrew (July 14, 1994). "Defining the Netplex". Washington Technology Magazine. Retrieved October 12, 2007.

- "Dulles Metro/Silver Line Stations". Dulles Metro. Retrieved May 17, 2018.

- "RIBS". LINK. Retrieved October 12, 2007.

- "Fairfax Connector Celebrates 20 Years". Washington Post. November 7, 2005. Retrieved October 12, 2007.

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Reston CDP, Virginia". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Retrieved October 14, 2016.

- Climate Summary for Reston, Virginia

- "WeatherBase". WeatherBase. Retrieved April 8, 2020.

- "South Lakes High School attendance map" (PDF). Retrieved May 9, 2009.

- "Herndon High School attendance map" (PDF). Retrieved May 9, 2009.

- Edlin School

- "Library Branches." Fairfax County Public Library. Retrieved on October 21, 2009.

- "Reston CDP, Virginia." U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved on October 21, 2009.

- "Reston CDP, Virginia". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 10, 2020. Retrieved October 12, 2007.

- Reston CDP, Virginia - Fact Sheet - American FactFinder

- "Reston, VA". Money Magazine. Retrieved October 12, 2007.

- "General Information: A Quick Reference" (PDF). Reston Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 30, 2007. Retrieved October 12, 2007.

- "The First Amendment to the Deed of Amendment to the Deeds of Dedication of Reston" (PDF). Reston Association. Section V.7. Basis for Assessments: Reston Association. p. 23. Retrieved September 8, 2017.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Virginia's 8th District | Congressman Gerry Connolly: 11th District Retrieved October 9, 2015.

- "THE ADVANTAGES AND DISADVANTAGES OF THE INCORPORATION OF RESTON AS A TOWN" (PDF). Reston Community Association. September 1, 1978. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 14, 2008. Retrieved October 12, 2007.

- "Print subscriptions for the Washington Post". Washington post. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- "Subscription options for the Washington Times". Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- "About the Fairfax Times". Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- Neibauer, Michael (June 9, 2010). "Herndon's Observer newspaper shuts down". Washington Business Journal. Retrieved August 9, 2010.

- Reston Now

- "Radio stations in the Washington, D.C., metro area". Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- http://virus.stanford.edu/filo/ebor.html "Ebola Reston Outbreaks". Department of Human Virology, Stanford University

- Koubaroulis, BJ (August 15, 2006). "Grant Hill, South Lakes Basketball". Connection Newspapers. Retrieved March 22, 2010.

- Associated Press (August 17, 1988). "Roy Buchanan, 48, a Guitarist". New York Times. Retrieved April 30, 2009.

- "Coalition for a Planned Reston". Planned Reston. January 2018. Retrieved May 15, 2018.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Reston, Virginia. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Reston. |

- Reston Association – The official association website

- Reston Museum – The official website of the Reston Historic Trust and its Reston Museum.

- Reston Planned Community Archives – online images and articles from the Special Collections and Archives of George Mason University.

- Beyond DC Reston gallery

- Wolf Von Eckardt, The Row House Revival is Going to Town–Not to Mention Country; Washington Post; July 24, 1966

- Reston, Virginia at Curlie