Manassas, Virginia

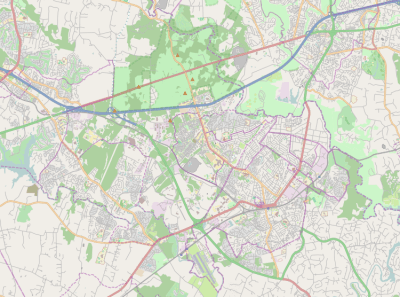

Manassas (/məˈnæs əs/;[8] formerly Manassas Junction)[9] is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia. As of the 2010 census, the population was 37,821.[10] The city borders Prince William County, and the independent city of Manassas Park, Virginia. The Bureau of Economic Analysis includes both Manassas and Manassas Park with Prince William County for statistical purposes.

Manassas, Virginia | |

|---|---|

| City of Manassas | |

View of downtown Manassas looking east on Center Street. | |

Flag  Seal | |

Manassas  Manassas  Manassas | |

| Coordinates: 38°45′5″N 77°28′35″W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Pre-incorporation County | |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council-Manager |

| • Mayor | Harry J. (Hal) Parrish II[1] |

| • City Manager | W. Patrick Pate[2] |

| • Vice Mayor | Pamela J. Sebesky[1] |

| • City Council | Members[1]

|

| Area | |

| • Total | 9.90 sq mi (25.64 km2) |

| • Land | 9.84 sq mi (25.49 km2) |

| • Water | 0.06 sq mi (0.15 km2) |

| Elevation | 305 ft (93 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 37,821 |

| • Estimate (2019)[4] | 41,085 |

| • Density | 4,174.03/sq mi (1,611.60/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP codes | 20108 (PO Box Only), and 20110[5] |

| Area codes | 703, 571 |

| FIPS code | 51-48952[6] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1498512[7] |

| Website | ManassasCity.org |

Manassas also serves as the seat of Prince William County. It surrounds the 38-acre (150,000 m2) county courthouse, but that county property is not part of the city. The City of Manassas has several important historic sites from the period 1850–1870.

The City of Manassas is part of the Washington-Arlington-Alexandria, DC-VA-MD-WV Metropolitan Statistical Area and is in the Northern Virginia region.

History

In July 1861, the First Battle of Manassas—also known as the First Battle of Bull Run—was fought nearby, the first major land battle of the American Civil War. Manassas commemorated the 150th anniversary of the First Battle of Manassas on July 21–24, 2011.[11]

The Second Battle of Manassas (or the Second Battle of Bull Run) was fought near Manassas on August 28–30, 1862. At that time, Manassas Junction was little more than a railroad crossing, but a strategic one, with rails leading to Richmond, Virginia, Washington, D.C., and the Shenandoah Valley. Despite these two Confederate victories, Manassas Junction was in Union hands for most of the war.

Following the war, the crossroads grew into the town of Manassas, which was incorporated in 1873. In 1894, Manassas was designated the county seat of Prince William County, replacing Brentsville. In 1975, Manassas was incorporated as an independent city, and as per Virginia law, was separated from Prince William County.

The Manassas Historic District; Cannon Branch Fort; Liberia, a plantation house; and the Manassas Industrial School for Colored Youth are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[12]

Geography

Manassas is mainly served by I-66, U.S. 29, Virginia State Route 234 Business and Virginia State Route 28.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 9.9 square miles (25.6 km2), of which 9.9 square miles (25.6 km2) is land and 0.1 square miles (0.3 km2) (0.5%) is water.[13]

Manassas has a council-manager system of government. As of October 2019 the city manager is William Patrick Pate; the mayor is Harry J. Parrish II; and the vice mayor is Pamela J. Sebesky.[1][2]

Climate

The climate in this area is characterized by hot, humid summers and generally mild to cool winters. According to the Köppen Climate Classification system, Manassas has a humid subtropical climate, abbreviated "Cfa" on climate maps.[14]

Neighborhoods

Some neighborhoods within the City of Manassas include:

Georgetown South

Georgetown South is a PUD 30 miles south of downtown Washington, D.C. in Manassas.[15] When it was built in the 1960s, it was seen as a "tony, southern sister for the District’s famous and affluent Georgetown".[16] It is composed entirely of 3-bedroom, 2-story red brick townhomes built between 1960 and 1970, some with exteriors painted in creams or pastels. The neighborhood features a community center that offers a walk-in pediatric clinic, seminars, workshops, and citizenship courses.[16] In spite of high hopes during construction, the neighborhood was hit extremely hard during the foreclosure crisis. "At the height of the housing bubble, nearly 60 percent of residents were homeowners," but in 2013, 60% of residents were renters.[16] As houses eventually became vacant, they left in their wake room for crime to creep in. Today, the neighborhood is known more for its elevated crime rate, including the use of drugs and violent domestic crimes, than it is for its history or connection to the nation's capital.[16]

Downtown

Historic Downtown Manassas, also called the Manassas Historic District or Old Town Manassas, is a neighborhood in the city-center of Manassas. According to Historic Manassas, this seven-by-one-block area alone contains 206 buildings and one contributing object.[17] Its northern border is Portner Avenue and its southern border is Prince William Street.[18] As recently as the early 1990s, Downtown Manassas was known to be rundown, and was primarily used by workers commuting from the area into Washington, D.C. In 1995, however, local businessowner Loy E. Harris founded Historic Manassas and invested in the area in an effort to bring it back to life. Harris's death in 1999 from cancer was felt in the community,[19] but his organization, Historic Manassas, remained. In the 2010s, further efforts were made to make the area successful not only commercially but residentially. Developers seized the opportunity and constructed three- and four-story townhomes along eastern Center Street, eastern Church Street, and Prescott Avenue to usher in a younger generation of homeowners seeking urban amenities in a suburban setting. On the opposite end of the neighborhood sits the Harris Pavillion, an outdoor venue that is converted to an ice skating rink in the winter.[20] Just south of Old Town sits the Manassas Museum, which commemorates the city's history and involvement in the American Civil War.[21] Downtown Manassas contains several notable buildings:

- Manassas Presbyterian Church (1875)

Old Town Triangle

The Old Town Triangle is a historic residential district adjacent to Old Town Manassas. It is named for its triangular shape, with three street borders: Grant Avenue, Sudley Road, and Portner Avenue.[18] The Old Town Triangle mostly comprises spacious colonial, manor, and single-story homes built between 1900 and 1955.[22] They are valued substantially higher than similar homes in adjacent neighborhoods.[22] The Old Town Triangle contains some of Manassas's most notable buildings, including:

- Annaburg Manor, a historic manor that was once converted to a senior living facility,[23] and was purchased by the City of Manassas in July 2019 to be restored to its original design by an interested nonprofit. Built in 1892, the manor was the original home of Robert Portner. It was reportedly one of the first in the country to have mechanical air conditioning.[24]

- Annaburg Manor Gatehouse, non-operable gatehouse for historic Liberia Manor[23]

- Bennett House, a historic home converted to a bed-and-breakfast[25]

The Old Town Triangle also contains two recreational parks:[26]

Adjacent & Nearby Areas

- Prince William County, Virginia – northwest, west, south, east

- Manassas Park, Virginia – northeast

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1880 | 361 | — | |

| 1890 | 530 | 46.8% | |

| 1900 | 817 | 54.2% | |

| 1910 | 1,217 | 49.0% | |

| 1920 | 1,305 | 7.2% | |

| 1930 | 1,215 | −6.9% | |

| 1940 | 1,302 | 7.2% | |

| 1950 | 1,804 | 38.6% | |

| 1960 | 3,555 | 97.1% | |

| 1970 | 9,164 | 157.8% | |

| 1980 | 15,438 | 68.5% | |

| 1990 | 27,957 | 81.1% | |

| 2000 | 35,135 | 25.7% | |

| 2010 | 37,821 | 7.6% | |

| Est. 2019 | 41,085 | [4] | 8.6% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[27] 1790-1960[28] 1900-1990[29] 1990-2000[30] | |||

According to the census[31] of 2010, the population of the City of Manassas was 37,821 which represented a 7.6% growth in population since the last census in 2000. The racial breakdown per the 2010 Census for the City is as follows:

- 65.3% White

- 15.7% Black

- 5.9% Asian

- 16.2% Other

31.4% of the population was of Hispanic or Latino origin. This can be broken up ethnically as follows:

- 9.9% Mexican

- 1.1 Puerto Rican

- 0.2% Cuban

- 20.2% other Hispanic or Latino

The population density for the city is 3,782.1 people per square mile, and there are an estimated 13,103 housing units in the city with an average housing density of 1,310.3 per square mile.[32] The greatest percentage of housing values of owner-occupied homes (34.8%) is $300,000 to $499,999, with a median owner-occupied housing value of $259,100. The City's highest period of growth was from 1980 to 1989, when 35% of the City's housing stock was constructed.[33]

The ACS estimated median household income for the City in 2010 was $70,211. 36% of the population has a college degree.[32] Almost as many people commute into the City of Manassas for work (13,316) as out (13,666), with the majority of out commuters traveling to Fairfax and Prince William counties for their jobs. Unemployment as of July, 2010 in the City is 6.3%, which was well below that of the United States at 7.9%. City residents are primarily employed in Professional, Scientific and Technical Services, and Health Care and Social Assistance.[34]

Politics

For many years, Manassas was one of the more conservative areas of Virginia, but in 2008, it swung dramatically to the Democrats, going from a 13-point victory for George W. Bush to an 11-point win for Barack Obama. It has supported Democratic presidential candidates by double-digit margins in the last three elections, partly due to the larger Democratic trend in Northern Virginia.

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third Parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 38.6% 5,953 | 54.7% 8,423 | 6.7% 1,035 |

| 2012 | 42.5% 6,463 | 55.8% 8,478 | 1.9% 259 |

| 2008 | 43.8% 5,975 | 55.2% 7,518 | 1.0% 134 |

| 2004 | 56.2% 7,257 | 43.1% 5,562 | 0.7% 84 |

| 2000 | 54.4% 6,752 | 42.4% 5,262 | 3.2% 396 |

| 1996 | 52.9% 5,799 | 39.9% 4,378 | 7.1% 783 |

| 1992 | 48.9% 5,453 | 32.7% 3,647 | 18.4% 2,054 |

| 1988 | 68.6% 5,980 | 30.5% 2,658 | 0.9% 81 |

| 1984 | 71.3% 4,613 | 28.2% 1,824 | 0.4% 29 |

| 1980 | 60.8% 3,009 | 31.6% 1,565 | 7.6% 378 |

| 1976 | 53.3% 1,992 | 44.0% 1,646 | 2.6% 99 |

Crime

During the second quarter of 2014, crime in the City of Manassas has decreased by 9 percent.[36] Calls for service from residents have decreased 27 percent from 2013 to 2014. Overall crime in the City of Manassas has steadily decreased over the years, as it has nationwide. About 1 in 5 reports taken during the 2nd quarter of 2014 was for a part 1 crime. The number of aggravated assaults reported in 2014 year-to-date and during the second quarter has increased by about half when compared to 2013 cases (+46%, +64%, respectively). Part 1 property crimes decreased by 19 cases during the 2nd quarter of 2014 (burglary, larceny, and auto theft). Overall, year-to-date totals indicate decreases in part 1 crimes (-14%) and all other offenses reported to police (-9%).[36]

Crime in Manassas has been rated by Neighborhood Scout to be more dangerous than 63% of all American neighborhoods and 37% safer than all American neighborhoods. That shows that Manassas has a moderately higher crime rate than average.[37] The website SiteJabber had numerous reviews that said Neighborhood Scout was an unreliable business that promoted poor practices and did not have accurate crime reports. From a total of eleven reviews, Neighborhood Scout was ranked at 1.5 stars, out of 5.[38]

Economy

The Manassas Regional Airport has 26 businesses operating out of the airport property. There are 415 based airplanes and two fixed-base operators, APP Jet Center and Dulles Aviation. The Manassas Regional Airport has land available for development.[39]

The city's third-largest employer is Micron Technology. Headquartered in Boise, Idaho, this manufacturer of semiconductors operates its wafer factory in Manassas, where it employs 1650 people directly, and several hundred others through vendor contracts. In December 2018, Micron began a $3 billon-dollar expansion project at the Manassas site, and it's expected to create 1,100 jobs by 2030.[40] Other major employers include Lockheed Martin (1500 employees) and the Novant Prince William Health System (1400 employees).

11% of people working in Manassas live in the city, while 89% commute in. 36% commute from Prince William County and 18% commute from Fairfax. Additionally 16,700 people commute from Manassas to the surrounding areas. In 2016, 3.3% of Manassas residents were unemployed.[41]

Transportation

_from_the_ramp_connecting_southbound_Virginia_State_Route_28_(Nokesville_Road)_to_southbound_Virginia_State_Route_234_in_Manassas%2C_Virginia.jpg)

Major highways

The major roads into and out of Manassas are Virginia State Route 28, Virginia State Route 234 and Virginia State Route 234 Business. I-66 and US-29 service Manassas, but neither passes through the city itself.

Airports

Manassas Regional Airport is within the city limits. It is the busiest general aviation airport in Virginia, with more than 415 aircraft and 26 businesses based onsite, including charter companies, avionics, maintenance, flight schools and aircraft services.

Rail transportation

Manassas began life as Manassas Junction, so named for the railroad junction between the Orange and Alexandria Railroad and the Manassas Gap Railroad. The O&A owned the railway from Alexandria through Manassas to points south, ending in Orange, Virginia, while the MGRR was an independent line constructed from Manassas Junction through the Manassas Gap westward. In addition Manassas was the site of the first large scale military use of railroad transportation.

These original routes are now owned by the Norfolk Southern railroad. Amtrak and the Virginia Railway Express (VRE) provide regular inter-city and commuter service to the city and surrounding area on the tracks owned by NS. Manassas station is served by VRE and three Amtrak routes: the New York City to Chicago Cardinal, Boston to Roanoke Northeast Regional, and New York to New Orleans Crescent.

The train station was also used for the cover photo for the Manassas (album).

Education

Public education

The City of Manassas is served by the Manassas City Public Schools. There are five elementary schools in Manassas, two intermediate schools, a middle school, and a high school. In 2006, Mayfield Intermediate School opened, serving students in fifth and sixth grade. Due to growth, Baldwin Intermediate School opened in September 2017, also serving 5th and 6th graders.

Some schools in the Prince William County Public Schools district have Manassas addresses, though they are located, and serve areas, outside the Manassas city limits.

Seton School, a private Roman Catholic junior and senior high school affiliated with the Diocese of Arlington, provides Catholic education from its Manassas location.[42] The All Saints Catholic School at the All Saints Parish provides Catholic Education from pre-K through 8th grade. The All Saints Catholic School was a Presidential Blue Ribbon Award winner in 2009.[43]

Also in the vicinity of Manassas are branch campuses of American Public University System, George Mason University, Northern Virginia Community College, ECPI College of Technology and Strayer University. Though some of these are just outside the city limits in Prince William County, NVCC and Strayer call these branches their Manassas Campuses.

Public schools in Manassas:[44]

- Baldwin Elementary School[45]

- Jennie Dean Elementary School[46]

- Richard C. Haydon Elementary School[47]

- George C. Round Elementary School[48]

- Weems Elementary School[49]

- Baldwin Intermediate School[50]

- Mayfield Intermediate School[51]

- Grace E. Metz Middle School[52]

- Osbourn High School[53]

- Northern Virginia Community College - Manassas[54]

Private education

Most private schools in Manassas are associated with religious institutions, like All Saints Catholic Church[55] or St. Thomas Methodist Church.[56] But some private schools in the area are based in other non-traditional schooling ideologies, such as the Reggio-Emilia[57] approach or trademarked curriculum such as the F.L.EX.® Learning Program.[58]

Private schools in Manassas:

- Ad Fonte Academy, a K-12 non-denominational Christian college preparatory school[59]

- All Saints Catholic School,[60] a Catholic Pre-K and K-8 school operated by All Saints Catholic Church[55]

- The Compass School,[61] a non-traditional Kindergarten and preschool that attributes its methods to the Reggio-Emilia approach[57]

- Emmanuel Christian School, a Baptist Elementary School operated by Emmanuel Baptist Church[62]

- The Goddard School of Manassas, a private elementary school using a trademarked curriculum[58]

- Harmony Montessori School, a private preschool following the Maria Montessori method[63]

- La Petite Academy, a STEM-oriented pre-school[64][65]

- Manassas Christian School, a Christian K-8 school[66] that accepts I-20 students[67]

- The Merit School - Manassas,[68] a preschool and elementary school with sister locations throughout Virginia[69]

- The Merit School - Old Town Manassas,[70] a preschool and elementary school with sister locations throughout Virginia[69]

- Minnieland Academy,[71] a local kindergarten and preschool chain with three Manassas locations[71]

- Prince William Technology Academy, a private secondary school serving grades 7-12[72]

- Seton School,[73] a Catholic high school founded in 1975[74]

- Sunbeam Children's Center,[56] a Christian preschool operated by St. Thomas Methodist Church[56]

Notable people

- Jim Bucher (1911–2004), infielder and outfielder in Major League Baseball

- Ryan Burroughs, professional rugby league footballer currently playing for Toronto Wolfpack

- Mason Diaz, NASCAR driver

- Danny Doyle, Irish folk singer[75]

- Wilmer Fields, pitcher and third baseman in Negro league baseball

- Brandon Hogan, football player

- Chaney Kley (1972–2007), American film and television actor

- Jon Knott, Major League Baseball outfielder

- Jeremy Linn, 1996 Summer Olympics swimmer and current swimming coach

- Mike O'Meara, radio personality[76][77][78]

- Harry J. Parrish (1922–2006), longtime member of the Virginia House of Delegates

- Leven Powell, also Levin, (1737–1810), U.S. Representative from Virginia

- Jason Richardson, American guitarist

- Kevin Ricks, an infamous serial sex offender[79]

- David Robinson, American basketball player

- Danica Roem, the first ever openly transgender woman to be elected to a US legislature

- Ravi Shankar, American poet

- Joanna Mary Berry Shields, teacher and founder of Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Inc.

- C. J. Sapong, American soccer player currently playing for Sporting Kansas City

- Leeann Tweeden, model

- Lucky Whitehead, former National Football League wide receiver

- Ryan Williams, running back for the Dallas Cowboys

- George Zimmerman[80]

See also

- Manassas Police Department

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Manassas, Virginia

References

- "Mayor & City Council: Manassas, VA - Official Site". www.manassascity.org. Retrieved 3 April 2019.

- "City Manager's Office: Manassas, VA - Official Site". www.manassascity.org. Retrieved 3 April 2019.

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- Manassas, VA ZIPs Retrieved November 22, 2009/April 6, 2012

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "Definition of manassas". Dictionary.com. Retrieved December 12, 2019.

- Contributed by The Hornbook of Virginia History. "Cities of Virginia". Encyclopedia Virginia. Retrieved 2014-01-21.

- "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on January 6, 2014. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- "Manassas Civil War Commemorative Event, July 21–24, 2011". Historic Manassa, Inc. Archived from the original on 2011-05-05.

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- "Climate Summary for Manassas, Virginia". Weatherbase.com. Retrieved 2014-01-21.

- "Georgetown South Community Council ~ Home". Retrieved 2019-09-05.

- Borden, Jeremy (13 September 2013). "Georgetown South in Manassas A Neighborhood Remaking Itself". The Washington Post. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- Waters. "Visit Manassas". Historic Manassas. Retrieved 2019-09-05.

- "Google Maps". Google Maps. Retrieved 2019-09-05.

- Grech, Daniel A. (18 August 1999). "Entrepreneur Who Revitalized Old Town Dies". The Washington Post. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- "Harris Pavilion | Manassas, VA - Official Site". www.manassascity.org. Retrieved 2019-09-05.

- "Manassas Museum - Virginia Is For Lovers". www.virginia.org. Retrieved 2019-09-05.

- "Real Estate & Homes For Sale (Manassas, VA)". www.zillow.com. Retrieved 2019-09-05.

- Novant Health UVA Health System. "Caton Merchant House". Novant Health UVA Health System. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- https://www.insidenova.com/news/local/manassas/manassas-finalizes-purchase-of-annaburg-manor/article_e3984358-a291-11e9-8353-13bd16caca52.html

- "Bennett House Bed & Breakfast in Historic Manassas Virginia is under construction". Retrieved 2019-09-07.

- "Parks | Manassas, VA - Official Site". www.manassascity.org. Retrieved 2019-09-07.

- "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2011-05-14.

- American Community Survey (ACS)

- City of Manassas, Department of Community Development

- Virginia Employment Commission, 1st Quarter, 2012

- Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- http://www.manassascity.org/DocumentCenter/View/23188

- "Manassas Crime Rates and Statistics - NeighborhoodScout". www.neighborhoodscout.com. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- "Neighborhood Scout", SiteJabber.com, 2008-2018

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-02-09. Retrieved 2015-02-09.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- https://www.insidenova.com/news/business/prince_william/construction-hiring-begins-for-micron-s-b-expansion-in-manassas/article_31ff6a20-f974-11e8-92e7-eba87753e09d.html

- Community Profile: Manassas Archived 2017-11-17 at the Wayback Machine, Virginia LMI

- "Welcome to Seton School - Private Catholic High School". Seton School Manassas. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- "Home - All Saints Catholic School". All Saints Catholic School. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- "Manassas City Public Schools - MCPS Home". Manassas City Public Schools. 2017. Retrieved 2017-07-03.

- "Baldwin Elementary / Homepage". www.mcpsva.org.

- "Jennie Dean Elementary / Homepage". www.mcpsva.org.

- "Haydon Elementary / Homepage". www.mcpsva.org.

- "Round Elementary / Homepage". www.mcpsva.org.

- "Weems Elementary / Homepage". www.mcpsva.org.

- "Baldwin Intermediate / Homepage". www.mcpsva.org.

- "Mayfield Intermediate / Homepage". www.mcpsva.org.

- "Metz Middle School / Homepage". www.mcpsva.org.

- "Osbourn High School / Homepage". www.mcpsva.org.

- "Manassas Campus :: Northern Virginia Community College". www.nvcc.edu. Retrieved 2019-09-03.

- "About All Saints". All Saints Catholic School. Retrieved 2019-09-03.

- "Sunbeam Children's Center - St. Thomas UMC - church in Manassas VA". www.stthomasumc.org. Retrieved 2019-09-03.

- "The Reggio Emilia Philosophy of Learning". The Compass School. Retrieved 2019-09-03.

- "The Goddard School". campaign.goddardschool.com. Retrieved 2019-09-03.

- "Ad Fontes Academy Private Christian School Northern Virginia". Ad Fontes Academy. Retrieved 2019-09-03.

- "Home". All Saints Catholic School. Retrieved 2019-09-03.

- "Preschool & Child Care | Manassas, VA". The Compass School. Retrieved 2019-09-03.

- "Emmanuel Christian School Manassas Virginia". Emmanuel Christian School Manassas Virginia. Retrieved 2019-09-03.

- "Harmony Montessori School - Manassas, VA". Yelp. Retrieved 2019-09-03.

- "La Petite Academy of Manassas in Manassas, VA | 10023 Dumfries Road | La Petite Academy". www.lapetite.com. Retrieved 2019-09-03.

- "STEM-inspired curriculum| La Petite Academy". www.lapetite.com. Retrieved 2019-09-03.

- "Welcome to Manassas Christian School". Manassas Christian School. Retrieved 2019-09-03.

- "I-20 Certified School". Manassas Christian School. Retrieved 2019-09-03.

- "Merit School of Manassas offers the best in early childhood education". The Merit School. Retrieved 2019-09-03.

- "Welcome to The Merit School". The Merit School. Retrieved 2019-09-03.

- "Merit School of Old Town Manassas". The Merit School. Retrieved 2019-09-03.

- "All School Locations - Minnieland Academy". Retrieved 2019-09-03.

- "Explore Prince William Regional Technology Academy in Manassas, VA". GreatSchools.org. Retrieved 2019-09-03.

- "Welcome to Seton School - Private Catholic High School". Seton School Manassas. Retrieved 2019-09-03.

- "About". Seton School Manassas. Retrieved 2019-09-03.

- "Oh Danny Boy, the Pipes …". Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- "Radio's Mike O'Meara". wcsh6.com. 2011-08-18. Retrieved 2012-05-14.

- AUDIO: Radio Host Mike O'Meara Blasts Adam Carolla's Anti-Occupy Rant Archived 2012-02-05 at the Wayback Machine. National Confidential (2011-12-03). Retrieved on 2014-03-21.

- "Virginia church turns to Hindu temple [newKerala.com News # 140512-191333]". Newkerala.com. Retrieved 2012-05-14.

- White, Josh (22 January 2013). "Kevin Ricks, former Manassas teacher, sentenced to 20 more years in prison". The Washington Post. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

- "Trayvon Martin shooter George Zimmerman has Manassas ties". The Washington Post. March 22, 2012.