Trieste

Trieste (/triˈɛst/ tree-EST,[3] Italian: [triˈɛste] (![]()

Trieste | |

|---|---|

| Comune di Trieste | |

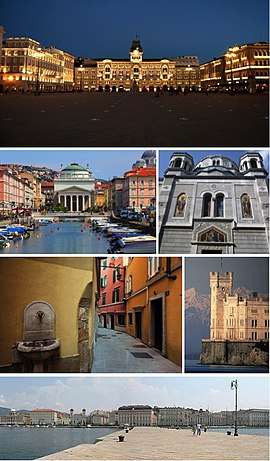

A collage of Trieste showing the Piazza Unità d'Italia, the Canal Grande (Grand Canal), the Serbian Orthodox church, a narrow street of the Old City, the Castello Miramare, and the city seafront | |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

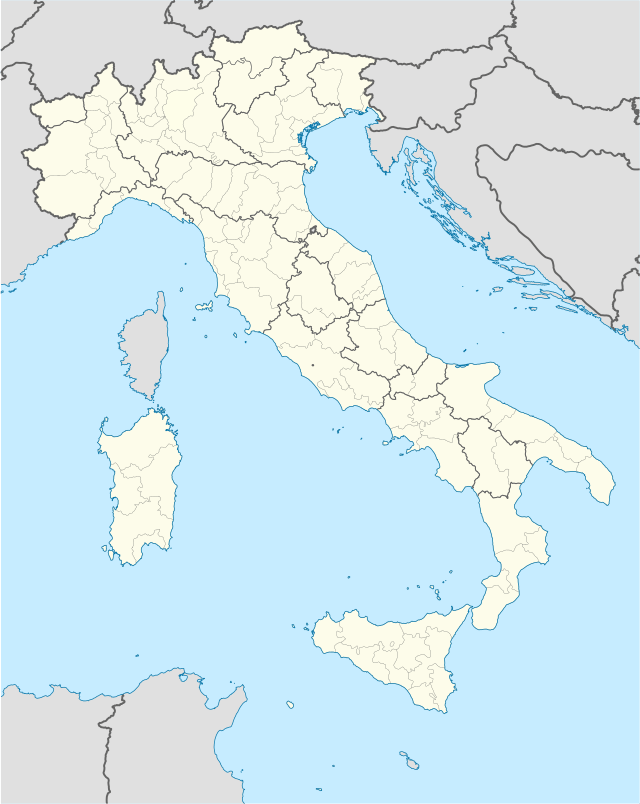

Location of Trieste

| |

Trieste Location of Trieste in Italy  Trieste Trieste (Friuli-Venezia Giulia) | |

| Coordinates: 45°38′N 13°48′E | |

| Country | Italy |

| Region | Friuli-Venezia Giulia |

| Frazioni | Banne (Bani), Barcola (Barkovlje), Basovizza (Bazovica), Borgo San Nazario, Cattinara (Katinara), Conconello (Ferlugi), Contovello (Kontovel), Grignano (Grljan), Gropada (Gropada), Longera (Lonjer), Miramare (Miramar), Opicina (Opčine), Padriciano (Padriče), Prosecco (Prosek), Santa Croce (Križ), Servola (Škedenj), Trebiciano (Trebče) |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Roberto Dipiazza (FI) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 84.49 km2 (32.62 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 2 m (7 ft) |

| Population (2018)[2] | |

| • Total | 204,338 (Comune) 234,638 (Urban) 418,000 (Metro) |

| Demonym(s) | Triestino |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 34100 |

| Dialing code | 040 |

| Patron saint | St. Justus of Trieste |

| Saint day | November 3 |

| Website | Official website |

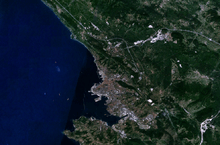

Trieste is at the head of the Gulf of Trieste and has a very long coastline, free sea access in Barcola and is surrounded by grassland, forest and karst areas. In 2018, it had a population of about 205,000[2] and it is the capital of the autonomous region Friuli-Venezia Giulia. The metropolitan population of Trieste is 410,000, with the city comprising about 240,000 inhabitants.

Trieste was one of the oldest parts of the Habsburg Monarchy, belonging to it from 1382 until 1918. In the 19th century the monarchy was one of the Great Powers of Europe and Trieste was its most important seaport. As a prosperous seaport in the Mediterranean region, Trieste became the fourth largest city of the Austro-Hungarian Empire (after Vienna, Budapest, and Prague). In the fin de siècle period at the end of the 19th century it emerged as an important hub for literature and music. Trieste underwent an economic revival during the 1930s, and the Free Territory of Trieste became a major site of the struggle between the Eastern and Western blocs after the Second World War.

Trieste, with its deep-water port, is a maritime gateway for Northern Italy, Germany, Austria and Central Europe, as it was before 1918 and is considered the end point of the Maritime Silk Road with its connections via the Suez Canal and Turkey and the other Overland to Africa, China, Japan and many countries in Asia. Since the 1960s, Trieste, thanks to its many international organizations and institutions, has been one of the most important research locations in Europe, an international school and university city and has one of the highest living standards among Italian cities. In 2020, the city was also rated as one of the 25 best small cities in the world in terms of quality-of-life.[4]

The city, which lies at the intersection of Latin, Slavic, Germanic, Greek and Jewish culture, where Central Europe meets the Mediterranean Sea, is considered one of the literary capitals and was often referred to as early New York because of its diverse ethnic groups and religious communities. There are also other national and international names for the city such as "Città della Barcolana", "Trieste città della bora", "città del vento", "Trieste città della scienza – City of Science", "City of the three winds", "Vienna by the sea" or "City of coffee" “, in which individual defining characteristics are emphasized.

Names and etymology

The original pre-Roman name of the city, Tergeste, with the -est- suffix typical of Venetic, is speculated to be derived from a hypothetical Illyrian word *terg- "market", etymologically related to Old Church Slavonic tьrgъ "market" (whence Western South Slavic trg, tržnica, Polish targ and the Scandinavian borrowing torg; cf. Oderzo, anciently Opitergium).[5][6][7] Roman authors also transliterated the name as Tergestum. Modern names of the city include: Italian: Trieste, Slovene: Trst, German: Triest, Hungarian: Trieszt, Croatian: Trst, Serbian: Трст/Trst, Polish: Triest, Greek: Τεργέστη/Tergesti and Czech: Terst.

Geography

Trieste lies in the northernmost part of the high Adriatic in northeastern Italy, near the border with Slovenia. The city lies on the Gulf of Trieste.

Built mostly on a hillside that becomes a mountain, Trieste's urban territory lies at the foot of an imposing escarpment that comes down abruptly from the Karst Plateau towards the sea. The karst landforms close to the city reach an elevation of 458 metres (1,503 feet) above sea level.

It lies on the borders of the Italian geographical region, the Balkan Peninsula, and the Mitteleuropa.

Climate

The territory of Trieste is composed of several different climate zones depending on the distance from the sea and elevation. The average temperatures (1971/2000) are 5.7 °C (42 °F) in January and 24.1 °C (75 °F) in July.[8] The climatic setting of the city is humid subtropical climate (Cfa according to Köppen climate classification). On average, humidity levels are pleasantly low (~65%), while only two months (January & February) receive slightly less than 60 mm (2 in) of precipitation.

Trieste along with the Istrian peninsula has evenly distributed rainfall above 1,000 mm (39 in) in total; it is noteworthy that no true summer drought occurs. Snow occurs on average 0 – 2 days per year.[9] Temperatures are very mild—lows below zero are somewhat rare and highs above 30 °C (86 °F) aren't as common as in other parts of Italy. Winter maxima are lower than in typical Mediterranean zone (~ 5–11 °C) but with quite high minima (~2–8 °C). Two basic weather patterns interchange—sunny, sometimes windy but often very cold days frequently connected to an occurrence of northeast wind called Bora as well as rainy days with temperatures about 6 to 11 °C (43 to 52 °F). Summer is very warm with maxima about 28 °C (82 °F) and lows above 20 °C (68 °F), with the hot nights being influenced by the warm sea water. The absolute maximum of the last 30 years is 38.0 °C (100 °F) in 2003, whereas the absolute minimum is −7.9 °C (18 °F) in 1996.

The Trieste area is divided into 8a–10a zones according to USDA hardiness zoning; Villa Opicina (320 to 420 MSL) with 8a in upper suburban area down to 10a in especially shielded and windproof valleys close to the Adriatic sea.

The climate can be severely affected by the Bora, a very dry and usually cool north-to-northeast katabatic wind that can last for some days and reach speeds of up to 140 km/h (87 mph) on the piers of the port, thus sometimes bringing subzero temperatures to the entire city.[10]

| Climate data for Trieste Barcola | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 18.2 (64.8) |

21.2 (70.2) |

23.9 (75.0) |

29.8 (85.6) |

32.2 (90.0) |

36.2 (97.2) |

37.6 (99.7) |

38.0 (100.4) |

34.4 (93.9) |

30.8 (87.4) |

24.4 (75.9) |

18.4 (65.1) |

38.0 (100.4) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 7.6 (45.7) |

9.0 (48.2) |

12.2 (54.0) |

16.5 (61.7) |

21.6 (70.9) |

25.0 (77.0) |

27.9 (82.2) |

27.7 (81.9) |

23.3 (73.9) |

17.8 (64.0) |

12.3 (54.1) |

8.8 (47.8) |

17.5 (63.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 5.7 (42.3) |

6.6 (43.9) |

9.4 (48.9) |

13.2 (55.8) |

18.1 (64.6) |

21.4 (70.5) |

24.1 (75.4) |

24.1 (75.4) |

20.1 (68.2) |

15.2 (59.4) |

10.2 (50.4) |

6.9 (44.4) |

14.6 (58.3) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 3.8 (38.8) |

4.3 (39.7) |

6.6 (43.9) |

10.0 (50.0) |

14.5 (58.1) |

17.8 (64.0) |

20.3 (68.5) |

20.4 (68.7) |

16.8 (62.2) |

12.7 (54.9) |

8.1 (46.6) |

5.0 (41.0) |

11.7 (53.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −7.5 (18.5) |

−7.1 (19.2) |

−6.3 (20.7) |

3.2 (37.8) |

6.0 (42.8) |

10.1 (50.2) |

12.3 (54.1) |

11.0 (51.8) |

7.0 (44.6) |

3.7 (38.7) |

−1.5 (29.3) |

−7.9 (17.8) |

−7.9 (17.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 58.0 (2.28) |

56.9 (2.24) |

63.4 (2.50) |

82.8 (3.26) |

84.2 (3.31) |

100.4 (3.95) |

62.1 (2.44) |

84.5 (3.33) |

103.4 (4.07) |

111.4 (4.39) |

107.4 (4.23) |

88.5 (3.48) |

1,003 (39.48) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 7.8 | 6.2 | 7.8 | 8.5 | 8.7 | 9.3 | 6.5 | 7.3 | 7.1 | 7.9 | 9.1 | 8.4 | 94.6 |

| Average snowy days | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 2.0 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 67 | 64 | 62 | 64 | 64 | 65 | 62 | 62 | 66 | 68 | 67 | 68 | 65 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 96.1 | 118.7 | 142.6 | 177 | 226.3 | 243 | 288.3 | 260.4 | 210 | 167.4 | 99 | 83.7 | 2,112.5 |

| Source 1: [Atlante Climatico d'Italia del Servizio Meteorologico dell'Aeronautica Militare, data 1971–2011] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Rivista Ligure "La neve sulle coste del Maditerraneo" [9] | |||||||||||||

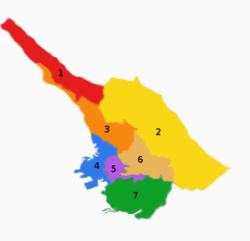

City districts

Trieste is administratively divided in seven districts:

- Altipiano Ovest: Borgo San Nazario · Contovello (Kontovel) · Prosecco (Prosek) · Santa Croce (Križ)

- Altipiano Est: Banne (Bani) · Basovizza (Bazovica) · Gropada (Gropada) · Opicina (Opčine) · Padriciano (Padriče) · Trebiciano (Trebče)

- Barcola (Slovene: Barkovlje)[11] · Cologna (Slovene: Kolonja)[11] · Conconello (Ferlugi) · Gretta (Slovene: Greta)[11] · Grignano (Grljan) · Guardiella (Slovene: Verdelj)[11] · Miramare · Roiano (Slovene: Rojan)[11] · Scorcola (Škorklja)

- Barriera Nuova · Borgo Giuseppino · Borgo Teresiano · Città Nuova · Città Vecchia · San Vito · San Giusto · Campi Elisi · Sant'Andrea · Cavana

- Barriera Vecchia (Stara Mitnica) · San Giacomo (Sveti Jakob) · Santa Maria Maddalena Superiore (Sveta Marija Magdalena Zgornja)

- Cattinara (Katinara) · Chiadino (Slovene: Kadinj)[11] · San Luigi · Guardiella (Verdelj) · Longera (Slovene: Lonjer)[11] · San Giovanni (Sveti Ivan)· Rozzol (Slovene: Rocol)[11] · Melara

- Chiarbola (Slovene: Čarbola)[11] · Coloncovez (Kolonkovec) · Santa Maria Maddalena Inferiore (Slovene: Spodnja Sveta Marija Magdalena)[11] · Raute · Santa Maria Maddalena Superiore (Slovene: Zgornja Sveta Marija Magdalena)[11] · Servola (Škedenj) · Poggi Paese · Poggi Sant'Anna (Sveta Ana)· Valmaura · Altura · Borgo San Sergio

The iconic city center is Piazza Unità d'Italia, which is between the large 19th-century avenues and the old medieval city, composed of many narrow and crooked streets.

History

Ancient history

Since the second millennium BC, the location was an inhabited site. Originally an Illyrian settlement, the Veneti entered the region in the 10th–9th c. BC and seem to have given the town its name, Tergeste, since terg* is a Venetic word meaning market (q.v. Oderzo whose ancient name was Opitergium). Still later, the town was captured by the Carni, a tribe of the Eastern Alps, before becoming part of the Roman republic in 177 BC during the Second Istrian War.

Between 52 and 46 BC, it was granted the status of Roman colony under Julius Caesar, who recorded its name as Tergeste in Commentarii de Bello Gallico (51 BC), his work which recounts events of the Gallic Wars.

In imperial times the border of Roman Italy moved from the Timavo river to Formione (today Risano). Roman Tergeste flourished due to its position on the road from Aquileia, the main Roman city in the area, to Istria, and as a port, some ruins of which are still visible. Emperor Augustus built a line of walls around the city in 33–32 BC, while Trajan built a theatre in the 2nd century. At the same time, the citizens of the town were enrolled in the tribe Pupinia. In 27 BC, Trieste was incorporated in Regio X of Augustan Italia.[12]

In the early Christian era Trieste continued to flourish. Between AD 138 and 161, its territory was enlarged and nearby Carni and Catali were granted Roman citizenship by the Roman Senate and Emperor Antoninus Pius at the pleading of a leading Tergestine citizen, the quaestor urbanus, Fabius Severus.

Already at the time of the Roman Empire there was a fishing village called Vallicula ("small valley") in the Barcola area. Remains of richly decorated Roman villas, including wellness facilities, piers and extensive gardens suggest that Barcola was already a popular place for relaxation and refinement among the Romans because of its favorable microclimate, as it was located directly on the sea and protected from the Bora. At that time, as Pliny the Elder mentioned, the vines of the wine Pulcino ("Vinum Pucinum" - today probably "Prosecco") were grown on the slopes.[13]

Late Antiquity

The city was witness to the Battle of the Frigidus in the Vipava Valley in AD 394, in which Theodosius I defeated Eugenius. Despite the deposition of Romulus Augustulus at Ravenna in 476 and the ascension to power of Odoacer in Italy, Trieste was retained for a time by the Roman Emperor seated at Constantinople, and thus became a Byzantine military outpost. In 539, the Byzantines annexed it to the Exarchate of Ravenna and, despite Trieste's being briefly taken by the Lombards in 567 in the course of their invasion of northern Italy, held it until the time of the coming of the Franks.

Middle Ages

In 788, Trieste submitted to Charlemagne, who placed it under the authority of their count-bishop who in turn was under the Duke of Friùli. From 1081 the city came loosely under the Patriarchate of Aquileia, developing into a free commune by the end of the 12th century.

During the 13th and 14th centuries, Trieste became a maritime trade rival to the Republic of Venice which briefly occupied it in 1283–87, before coming under the patronage of the Patriarchate of Aquileia. After it committed a perceived offence against Venice, the Venetian State declared war against Trieste in July 1368 and by November had occupied the city. Venice intended to keep the city and began rebuilding its defenses, but was forced to leave in 1372. By the Peace of Turin in 1381, Venice renounced its claim to Trieste and the leading citizens of Trieste petitioned Leopold III of Habsburg, Duke of Austria, to make Trieste part of his domains. The agreement of voluntary submission (dedizione) was signed at the castle of Graz on 30 September 1382.[14]

The city maintained a high degree of autonomy under the Habsburgs, but was increasingly losing ground as a trade hub, both to Venice and to Ragusa. In 1463, a number of Istrian communities petitioned Venice to attack Trieste. Trieste was saved from utter ruin by the intervention of Pope Pius II who had previously been bishop of Trieste. However, Venice limited Trieste's territory to three miles (4.8 kilometres) outside the city. Trieste would be assaulted again in 1468–1469 by Holy Roman Emperor Frederick III. His sack of the city is remembered as the "Destruction of Trieste."[15] Trieste was fortunate to be spared another sack in 1470 by the Ottomans who burned the village of Prosecco, only about 5.3 miles (8.5 kilometres) from Trieste, while on their way to attack Friuli.

Early modern period

Following an unsuccessful Habsburg invasion of Venice in the prelude to the 1508–16 War of the League of Cambrai, the Venetians occupied Trieste again in 1508, and were allowed to keep the city under the terms of the peace treaty. However, the Habsburg Empire recovered Trieste a little over one year later, when the conflict resumed. By the 18th century Trieste became an important port and commercial hub for the Austrians. In 1719, it was granted status as a free port within the Habsburg Empire by Emperor Charles VI, and remained a free port until 1 July 1791. The reign of his successor, Maria Theresa of Austria, marked the beginning of a very prosperous era for the city. Serbs settled Trieste largely in the 18th and 19th centuries, and they soon formed an influential and rich community within the city, as a number of Serb traders owned important business and had built palaces across Trieste.[16]

19th century

In the following decades, Trieste was briefly occupied by troops of the French Empire during the Napoleonic Wars on several occasions, in 1797, 1805 and 1809. From 1809 to 1813, Trieste was annexed into Illyrian Provinces, interrupting its status of free port and losing its autonomy. The municipal autonomy was not restored after the return of the city to the Austrian Empire in 1813. Following the Napoleonic Wars, Trieste continued to prosper as the Free Imperial City of Trieste (German: Reichsunmittelbare Stadt Triest), a status that granted economic freedom, but limited its political self-government. The city's role as Austria's main trading port and shipbuilding centre was later emphasized with the foundation of the merchant shipping line Austrian Lloyd in 1836, whose headquarters stood at the corner of the Piazza Grande and Sanità (today's Piazza Unità d'Italia). By 1913 Austrian Lloyd had a fleet of 62 ships comprising a total of 236,000 tons.[17] With the introduction of the constitutionalism in the Austrian Empire in 1860, the municipal autonomy of the city was restored, with Trieste becoming capital of the Austrian Littoral crown land (German: Österreichisches Küstenland).

In the later part of the 19th century, Pope Leo XIII considered moving his residence to Trieste or Salzburg because of what he considered a hostile anti-Catholic climate in Italy following the 1870 Capture of Rome by the newly established Kingdom of Italy. However, Emperor Franz Joseph rejected the idea.[18] The modern Austro-Hungarian Navy used Trieste as a base and for shipbuilding. The construction of the first major trunk railway in the Empire, the Vienna-Trieste Austrian Southern Railway, was completed in 1857, a valuable asset for trade and the supply of coal.

In 1882 an Irredentist activist, Guglielmo Oberdan, attempted to assassinate Emperor Franz Joseph, who was visiting Trieste. Oberdan was caught, convicted, and executed. He was regarded as a martyr by radical Irredentists, but as a cowardly villain by the supporters of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy. Franz Joseph, who reigned another thirty-four years, never visited Trieste again.

20th century

At the beginning of the 20th century, Trieste was a bustling cosmopolitan city frequented by artists and philosophers such as James Joyce, Italo Svevo, Sigmund Freud, Zofka Kveder, Dragotin Kette, Ivan Cankar, Scipio Slataper, and Umberto Saba. The city was the major port on the Austrian Riviera, and perhaps the only real enclave of Mitteleuropa (i.e., Central Europe) on the Mediterranean. Viennese architecture and coffeehouses dominate the streets of Trieste to this day.

World War I, annexation to Italy, and the Fascist era

Italy, in return for entering World War I on the side of the Allied Powers, had been promised substantial territorial gains, which included the former Austrian Littoral and western Inner Carniola. Italy therefore annexed the city of Trieste at the end of the war, in accordance with the provisions of the 1915 Treaty of London and the Italian-Yugoslav 1920 Treaty of Rapallo. While only a few thousands Italians remained in the newly established South Slavic [lower-roman 1] state, a population of half a million Slavs,[19] including the annexed Slovenes, were cut off from the remaining three-quarters of total Slovene population at the time and were subjected to forced Italianization. Trieste had a large Italian majority, but it had more ethnic Slovene inhabitants than even Slovenia's capital of Ljubljana at the end of 19th century.

The Italian lower middle class—who felt most threatened by the city's Slovene middle class—sought to make Trieste a città italianissima, committing a series of attacks led by Black Shirts against Slovene-owned shops, libraries, and lawyers' offices, even burning down the Trieste National Hall, a central building to the Slovene community.[20] By the mid-1930s several thousand Slovenes, especially members of the middle class and the intelligentsia from Trieste, emigrated to the Kingdom of Yugoslavia or to South America. Among the notable Slovene émigrés from Trieste were the author Vladimir Bartol, the legal theorist Boris Furlan and the Argentine architect Viktor Sulčič. The political leadership of the around 70,000 émigrés from the Julian March in Yugoslavia was mostly composed of Trieste Slovenes: Lavo Čermelj, Josip Vilfan and Ivan Marija Čok. In 1926, claiming that it was restoring surnames to their original Italian form, the Italian government announced the Italianization of German, Slovene and Croatian surnames.[21][22] In the Province of Trieste alone, 3,000 surnames were modified and 60,000 people had their surnames amended to an Italian-sounding form.[23] The psychological trauma, experienced by more than 150,000 people, led to a massive emigration of German and Slavic families from Trieste.[24] Despite the exodus of the Slovene and German speakers, the city's population increased because of the migration of Italians from other parts of Italy. Several thousand ethnic Italians from Dalmatia also moved to Trieste from the newly created Yugoslavia.[25]

In the late 1920s, resistance began with the Slovene militant anti-fascist organization TIGR, which carried out several bomb attacks in the city centre. In 1930 and 1941, two trials of Slovene activists were held in Trieste by the fascist Special Tribunal for the Security of the State. During the 1920s and 1930s, several monumental buildings were built in the Fascist architectural style, including the impressive University of Trieste and the almost 70 m (229.66 ft) tall Victory Lighthouse (Faro della Vittoria), which became a city landmark. The economy improved in the late 1930s, and several large infrastructure projects were carried out.[26]

The Fascist government encouraged some of the artistic and intellectual subcultures that emerged in the 1920s, and the city became home to an important avant-garde movement in visual arts, centered around the futurist Tullio Crali and the constructivist Avgust Černigoj. In the same period, Trieste consolidated its role as one of the centres of modern Italian literature, with authors such as Umberto Saba, Biagio Marin, Giani Stuparich, and Salvatore Satta. Intellectuals frequented the historic Caffè San Marco, still open today. Some non-Italian intellectuals remained in the city, such as the Austrian author Julius Kugy, the Slovene writer and poet Stanko Vuk, the lawyer and human rights activist Josip Ferfolja and the anti-fascist clergyman Jakob Ukmar.

The promulgation of the anti-Jewish racial laws in 1938 was a severe blow to the city's Jewish community, at the time the third largest in Italy. The fascist anti-semitic campaign resulted in a series of attacks on Jewish property and individuals, culminating in July 1942 when the Synagogue of Trieste was raided and devastated by the Fascist Squads and the mob.[27]

World War II and aftermath

With the annexation of the Province of Ljubljana by Italy and the subsequent deportation of 25,000 Slovenes, which equaled 7.5% of the total population of the Province, the operation, one of the most drastic in Europe, filled up Rab concentration camp, Gonars concentration camp, Monigo (Treviso), Renicci d'Anghiari, Chiesanuova, and other Italian concentration camps where altogether 9,000 Slovenes died,[28] World War II came close to Trieste. Following the trisection of Slovenia, starting from the winter of 1941, the first Slovene Partisans appeared in Trieste province, although the resistance movement did not become active in the city itself until late 1943.

After the Italian armistice in September 1943, the city was occupied by Wehrmacht troops. Trieste became nominally part of the newly constituted Italian Social Republic, but it was de facto ruled by Germany, who created the Operation Zone of the Adriatic Littoral out of former Italian north-eastern regions, with Trieste as the administrative centre. The new administrative entity was headed by Friedrich Rainer. Under German occupation, the only concentration camp with a crematorium on Italian soil was built in a suburb of Trieste, at the Risiera di San Sabba on 4 April 1944. About 5,000 South Slavs, Italian anti-Fascists and Jews died at the Risiera, while thousands more were imprisoned before being transferred to other concentration camps.

The city saw intense Italian and Yugoslav partisan activity and suffered from Allied bombings, over twenty raids in 1944–1945, targeting the oil refineries, port and marshalling yard but also causing considerable collateral damage to the city and 651 deaths among the population.[29] The worst raid took place on 10 June 1944, when a hundred tons of bombs dropped by forty USAAF bombers, targeting the oil refineries, resulted in the destruction of 250 buildings, damage to another 700 and 463 victims.[30][31][32]

The city's Jewish community was deported to extermination camps, where most of them died.

Yugoslav occupation

On 30 April 1945, the Slovenian and Italian anti-Fascist Osvobodilna fronta (OF) and National Liberation Committee (Comitato di Liberazione Nazionale, or CLN) of Marzari and Savio Fonda, made up of approximately 3,500 volunteers, incited a riot against the Nazi occupiers. On 1 May Allied members of the Yugoslav Partisans' 8th Dalmatian Corps took over most of the city, except for the courts and the castle of San Giusto, where the German garrisons refused to surrender to anyone other than New Zealanders. (The Yugoslavs had a reputation for shooting German and Italian prisoners.) The 2nd New Zealand Division under General Freyberg continued to advance towards Trieste along Route 14 around the northern coast of the Adriatic sea and arrived in the city the following day (see official histories The Italian Campaign[33] and Through the Venetian Line).[34] The German forces surrendered on the evening of 2 May, but were then turned over to the Yugoslav forces.

The Yugoslavs held full control of the city until 12 June, a period known in Italian historiography as the "forty days of Trieste".[35] During this period, hundreds of local Italians and anti-Communist Slovenes were arrested by the Yugoslav authorities, and many of them were never seen again.[36] Some were interned in Yugoslav concentration camps (in particular at Borovnica, Slovenia), while others were murdered on the Karst Plateau.[37] British Field Marshal Harold Alexander condemned the Yugoslav military occupation, stating that "Marshal Tito's apparent intention to establish his claims by force of arms . . . [is] all too reminiscent of Hitler, Mussolini and Japan. It is to prevent such actions that we have been fighting this war."[38][39]

After an agreement between the Yugoslav leader Josip Broz Tito and Field Marshal Alexander, the Yugoslav forces withdrew from Trieste, which came under a joint British-U.S. military administration. The Julian March was divided by the Morgan Line between Anglo-American and Yugoslav military administration until September 1947 when the Paris Peace Treaty established the Free Territory of Trieste.

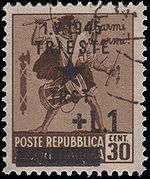

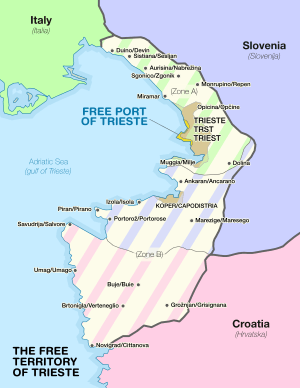

Zone A of the Free Territory of Trieste (1947–54)

In 1947, Trieste was declared an independent city state under the protection of the United Nations as the Free Territory of Trieste. The territory was divided into two zones, A and B, along the Morgan Line established in 1945.[40]

From 1947 to 1954, Zone A was occupied and governed by the Allied Military Government, composed of the American "Trieste United States Troops" (TRUST), commanded by Major General Bryant E. Moore, the commanding general of the American 88th Infantry Division, and the "British Element Trieste Forces" (BETFOR),[41] commanded by Sir Terence Airey, who were the joint forces commander and also the military governors.

Zone A covered almost the same area of the current Italian Province of Trieste, except for four small villages south of Muggia (see below), which were given to Yugoslavia after the dissolution (see London Memorandum of 1954) of the Free Territory in 1954. Occupied Zone B, which was under the administration of Miloš Stamatović, then a colonel in the Yugoslav People's Army, was composed of the north-westernmost portion of the Istrian peninsula, between the Mirna River and the cape Debeli Rtič.

In 1954, in accordance with the Memorandum of London, the vast majority of Zone A—including the city of Trieste—joined Italy, whereas Zone B and four villages from Zone A (Plavje, Spodnje Škofije, Hrvatini, and Elerji) became part of Yugoslavia, divided between Slovenia and Croatia. The final border line with Yugoslavia and the status of the ethnic minorities in the areas was settled bilaterally in 1975 with the Treaty of Osimo. This line now constitutes the border between Italy and Slovenia.

Government

This is a list of the mayors of Trieste since 1949:

| Mayor | Term start | Term end | Party | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gianni Bartoli | 1949 | 1957 | DC | |

| Mario Franzil | 1957 | 1967 | DC | |

| Marcello Spaccini | 1967 | 1978 | DC | |

| Manlio Cecovini | 1978 | 1983 | LpT | |

| Arduino Agnelli | 1983 | 1985 | PSI | |

| Franco Richetti | 1985 | 1986 | DC | |

| Giulio Staffieri | 1986 | 1988 | LpT | |

| Franco Richetti | 1988 | 1992 | DC | |

| Giulio Staffieri | 1992 | 1993 | LpT | |

| Riccardo Illy | 5 December 1993 | 24 June 2001 | Ind | |

| Roberto Dipiazza | 24 June 2001 | 30 May 2011 | FI | |

| Roberto Cosolini | 30 May 2011 | 20 June 2016 | PD | |

| Roberto Dipiazza | 20 June 2016 | incumbent | FI |

Economy

During the Austro-Hungarian era, Trieste became a leading European city in economy, trade and commerce, and was the fourth-largest and most important centre in the empire, after Vienna, Budapest and Prague. The economy of Trieste, however, fell into a decline after the city's annexation to Italy at the end of World War I. But Fascist Italy promoted a huge development of Trieste in the 1930s, with new manufacturing activities related even to naval and armament industries (like the famous "Cantieri Aeronautici Navali Triestini (CANT)").[42] Allied bombings during World War II destroyed the industrial section of the city (mainly the shipyards). As a consequence, Trieste was a mainly peripheral city during the Cold War. However, since the 1970s, Trieste has experienced a certain economic revival.

The city is part of the Corridor 5 project to establish closer transport connections between Western and Eastern Europe, via countries such as Slovenia, Croatia, Hungary, Ukraine and Bosnia.[43] The Port of Trieste is a trade hub with a significant commercial shipping business, busy container and oil terminals, and steel works. The oil terminal feeds the Transalpine Pipeline which covers 40% of Germany's energy requirements (100% of the states of Bavaria and Baden-Württemberg), 90% of Austria and more than 30% of the Czech Republic's.[44] The sea highway connecting the ports of Trieste and Istanbul is one of the busiest RO/RO [roll on roll-off] routes in the Mediterranean.The port is also Italy's and the Mediterranean's (and one of Europe's) greatest coffee ports, supplying more than 40% of Italy's coffee.[45]

The thriving coffee industry in Trieste began under Austria-Hungary, with the Austro-Hungarian government even awarding tax-free status to the city in order to encourage more commerce. Some remnants of Austria-Hungary's coffee-driven economic ambition remain, such as the Hausbrandt Trieste coffee company. As a result, present-day Trieste boasts many cafes, and is still known to this day as "the coffee capital of Italy". Companies active in the coffee sector have given birth to the Trieste Coffee Cluster as their main umbrella organization, but also as an economic actor in its own right.[46]

Two Fortune Global 500 companies have their global or national headquarters in the city, respectively: Assicurazioni Generali and Allianz. Other megacompanies based in Trieste are Fincantieri, one of the world's leading shipbuilding companies and the Italian operations of Wärtsilä. Prominent companies from Trieste include: AcegasApsAmga (Hera Group), Autamarocchi SpA, Banca Generali SpA (BIT: BGN), Genertel, Genertellife, HERA Trading, Illy, Italia Marittima, Modiano, Nuovo Arsenale Cartubi Srl, Jindal Steel and Power Italia SpA; Pacorini SpA, Sèleco, Siderurgica Triestina (Arvedi Group), TBS Groug, U-blox, Telit, and polling and marketing company SWG.

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1921 | 239,558 | — |

| 1931 | 250,170 | +4.4% |

| 1936 | 248,307 | −0.7% |

| 1951 | 272,522 | +9.8% |

| 1961 | 272,723 | +0.1% |

| 1971 | 271,879 | −0.3% |

| 1981 | 252,369 | −7.2% |

| 1991 | 231,100 | −8.4% |

| 2001 | 211,184 | −8.6% |

| 2009 Est. | 205,507 | −2.7% |

| 2013 | 204,849 | −0.3% |

| Source: ISTAT 2001 | ||

| ISTAT 2007[47] | ||

| Trieste, FVG | Italy | |

| Median age | 46 years | 42 years |

| Under 18 years old | 13.8% | 18.1% |

| Over 65 years old | 27.9% | 20.1% |

| Foreign Population | 6.2% | 5.8% |

| Births/1000 people | 7.63 b | 9.45 b |

As of 2013 there were 204,849 people residing in Trieste, located in the province of Trieste, Friuli-Venezia Giulia, of whom 46.7% were male and 53.3% were female. Trieste had lost roughly ⅓ of its population since the 1970s, due to the crisis of the historical industrial sectors of steel and shipbuilding, a dramatic drop in fertility rates and fast population aging. Minors (children aged 18 and younger) totalled 13.78% of the population compared to pensioners who number 27.9%. This compares with the Italian average of 18.06% (minors) and 19.94% (pensioners).

The average age of Trieste residents is 46 compared to the Italian average of 42. In the five years between 2002 and 2007, the population of Trieste declined by 3.5%, while Italy as a whole grew by 3.85%. However, in the last two years the city has shown signs of stabilizing thanks to growing immigration fluxes. The crude birth rate in Trieste is only 7.63 per 1,000, one of the lowest in eastern Italy, while the Italian average is 9.45 births.

Since the annexation to Italy after World War I, there has been a steady decline in the Trieste's demographic weight compared to other cities. In 1911, Trieste was the 4th largest city in the Austro-Hungarian Empire (3rd largest in the Austrian part of the Monarchy). In 1921, Trieste was the 8th largest city in the country,[48] in 1961 the 12th largest,[49] in 1981 the 14th largest,[50] while in 2011 it dropped to the 15th place.

At the end of 2012, ISTAT estimated that there were 16,279 foreign-born residents in Trieste, representing 7.7% of the total city population. The largest autochthonous minority are Slovenes, Croats and Serbs,[51] but there is also a large immigrant group from Balkan nations (particularly nearby Bosnia and Herzegovina, Albania and Romania): 4.95%, Asia: 0.52%, and sub-saharan Africa: 0.2%. Serbian community consists of both autochthonous[52] and immigrant groups.[53] Trieste is predominantly Roman Catholic, but also has large numbers of Orthodox Christians, mainly Serbs.

| Largest resident foreign-born groups (2018)[54] | |

|---|---|

| Country of birth | Population |

| 4,490 | |

| 2,976 | |

| 1,200 | |

| 1,195 | |

| 1,021 | |

| 705 | |

| 662 | |

| 646 | |

| 607 | |

| 518 | |

Language

The particular Friulian dialect, called Tergestino, spoken until the beginning of the 19th century, was gradually overcome by the Triestine dialect of Venetian (a language deriving directly from Vulgar Latin) and other languages, including standard Italian, Slovene, and German. While Triestine and Italian were spoken by the largest part of the population, German was the language of the Austrian bureaucracy and Slovene was predominantly spoken in the surrounding villages. From the last decades of the 19th century, the number of speakers of Slovene grew steadily, reaching 25% of the overall population of Trieste municipality in 1911 (30% of the Austro-Hungarian citizens in Trieste).[55]

According to the 1911 census, the proportion of Slovene speakers amounted to 12.6% in the city centre (15.9% counting only Austrian citizens), 47.6% in the suburbs (53% counting only Austrian citizens), and 90.5% in the surroundings.[56] They were the largest ethnic group in 9 of the 19 urban neighbourhoods of Trieste, and represented a majority in 7 of them.[56] The Italian speakers, on the other hand, made up 60.1% of the population in the city center, 38.1% in the suburbs, and 6.0% in the surroundings. They were the largest linguistic group in 10 of the 19 urban neighbourhoods, and represented the majority in 7 of them (including all 6 in the city centre). Of the 11 villages included within the city limits, the Slovene speakers had an overwhelming majority in 10, and the German speakers in one (Miramare). German speakers amounted to 5% of the city's population, with the highest proportions in the city centre.

The city also had several other smaller ethnic communities, including Croats, Czechs, Istro-Romanians, Serbs and Greeks, who mostly assimilated either into the Italian or the Slovene-speaking communities. Altogether, in 1911 51.83% of the population of the municipality of Trieste spoke Italian, 24.79% spoke Slovene, 5.2% spoke German, 1% spoke Croatian, 0.3% spoke "other languages", and 16.8% were foreigners, including a further 12.9% Italians (immigrants from the Kingdom of Italy and thus considered separately from Triestine Italians) and 1.6% Hungarians.[57]

By 1971, following the emigration of Slovenes to neighbouring Slovenia and the immigration of Italians from other regions (and from Yugoslav-annexed Istria) to Trieste, the percentage of Italian speakers had risen to 91.8%, and that of Slovenian speakers had dwindled to 5.7%.[58]

Today, the dominant local dialect of Trieste is Triestine ("Triestin", pronounced [triɛsˈtin]), influenced by a form of Venetian. This dialect and the official Italian language are spoken in the city, while Slovene is spoken in some of the immediate suburbs.[55] There are also small numbers of Serbian,[59] Croatian, German, Greek, and Hungarian speakers.

Main sights and vistas

In 2012, Lonely Planet listed the city of Trieste as the world's most underrated travel destination.[60]

Castles

Castello Miramare (Miramare Castle)

The Castello Miramare, or Miramare Castle, on the waterfront 8 kilometres (5 miles) from Trieste, was built between 1856 and 1860 from a project by Carl Junker working under Archduke Maximilian. The Castle gardens provide a setting of beauty with a variety of trees, chosen by and planted on the orders of Maximilian, that today make a remarkable collection. Features of particular attraction in the gardens include two ponds, one noted for its swans and the other for lotus flowers, the Castle annexe ("Castelletto"), a bronze statue of Maximilian, and a small chapel where is kept a cross made from the remains of the "Novara", the flagship on which Maximilian, brother of Emperor Franz Josef, set sail to become Emperor of Mexico.

Much later, the castle was also the home of Prince Amedeo, Duke of Aosta, the last commander of Italian forces in East Africa during the Second World War. During the period of the application of the Instrument for the Provisional Regime of the Free Territory of Trieste, as established in the Treaty of Peace with Italy (Paris 10/02/1947), the castle served as headquarters for the United States Army's TRUST force.

Castel San Giusto

The Castel San Giusto, or Castle of San Giusto, was designed on the remains of previous castles on the site, and took almost two centuries to build. The stages of the development of the Castle's defensive structures are marked by the central part built under Frederick III, Holy Roman Emperor (1470–1), the round Venetian bastion (1508–9), the Hoyos-Lalio bastion and the Pomis, or "Bastione fiorito" dated 1630.

Places of worship

- The St Justus Cathedral (1320). Named after the city's Patron, Justus of Trieste, the church's interiors are decorated with beautiful Byzantine mosaics. It became a symbol of Italian Trieste during the Risorgimento.

- The Serbian Orthodox Church of the Holy Trinity and St Spyridon (1869). The building adopts the Greek-cross plan with five cupolas in the Byzantine tradition. The parish forms part of the Metropolitanate of Zagreb, Ljubljana and all Italy.

- The Anglican Chiesa di Cristo (Christ Church) (1829)

- Sant'Antonio Taumaturgo (1842)

- The Mekhitarist Armenian Catholic Church (1859)

- The Waldensian and Helvetian Evangelical Basilica of St Silvester (11th century)

- The Church of Santa Maria Maggiore (1682)

- The Augustan Evangelical-Lutheran Church (1874)

- The Greek Orthodox Church of San Nicolò dei Greci (1787). This church by the architect Matteo Pertsch (1818), with bell towers on both sides of the façade, follows the Austrian late baroque style. The interiors are full of golden ornaments.

- The Synagogue of Trieste (1912)

- The Temple of Monte Grisa (1960), a Roman Catholic church north of the city

Archaeological remains

- Arch of Riccardo (33 BC)[61] is a Roman gate built in the Roman walls in 33. It stands in Piazzetta Barbacan, in the narrow streets of the old town. It's called Arco di Riccardo ("Richard's Arch"), where Riccardo is a corruption of "Cardus", the Roman street which crossed it. Folk etymology created a local legend, which says that it was crossed by King Richard I of England on the way back from the Crusades.

- Basilica Forense (2nd century)

- Palaeochristian basilica

- Roman Age Temples: one dedicated to Athena, one to Zeus, both on the San Giusto hill.

The ruins of the temple dedicated to Zeus are next to the Forum, those of Athena's temple are under the basilica, visitors can see its basement.

Roman theatre

The Roman theatre lies at the foot of the San Giusto hill, facing the sea. The construction partially exploits the gentle slope of the hill, and much of the theatre is made of stone. The topmost portion of the steps and the stage were supposedly made of wood.

The statues that adorned the theatre, brought to light in the 1930s, are now preserved at the town museum. Three inscriptions from the Trajanic period mention a certain Q. Petronius Modestus, someone closely connected to the development of the theatre, which was erected during the second half of the 1st century.

Caves

In the entire Province of Trieste, there are 10 speleological groups out of 24 in the whole Friuli-Venezia Giulia region. The Trieste plateau (Altopiano Triestino), called Kras or the Carso and covering an area of about 200 square kilometres (77 sq mi) within Italy has approximately 1,500 caves of various sizes (like that of Basovizza, now a monument to the Foibe massacres).

Among the most famous are the Grotta Gigante, the largest tourist cave in the world, with a single cavity large enough to contain St Peter's in Rome, and the Cave of Trebiciano, 350 metres (1,150 ft) deep, at the bottom of which flows the Timavo River. This river dives underground at Škocjan Caves in Slovenia (they are on UNESCO list and only a few kilometres from Trieste) and flows about 30 kilometres (19 mi) before emerging about 1 kilometre (0.6 mi) from the sea in a series of springs near Duino, reputed by the Romans to be an entrance to Hades ("the world of the dead").

Other

- The Austrian Quarter: Half of the city was built under Austro-Hungarian dominion, so there is present a very large number of avenues and palaces that resemble Vienna. The most present architecture styles are Neoclassical, Art Nouveau, Eclectic, Liberty and Baroque.

- Città Vecchia (Old City): Trieste boasts an extensive old city: there are many narrow and crooked streets with typical medieval houses. Nearly the entire area is closed to traffic.

- Piazza Unità d'Italia, Trieste's central majestic square surrounded by 19th century architecture, and the largest seafront square in Europe.

- Piazza Venezia, with a view over the Gulf of Trieste to Miramare Castle and the Alps with the Dolomite Mountains Civetta, Monte Pelmo and Antelao. Immediately in front of this square with its alley trees, the boats of the Trieste fishermen anchor on the Molo Veneziano. In the area towards Cavana there are now cosmopolitan-inspired bars, cafes and restaurants.

- Val Rosandra, a national park on the border between the Province of Trieste and Slovenia.

- Caffè San Marco, historical cafè in the centre of the city. Cafès play an important role in the Triestine economy, as Trieste developed a thriving coffee industry under Austria-Hungary, and is still known to this day as "the coffee capital of Italy".

- Barcola, a suburb of Trieste with a special microclimate and a high quality of life since ancient times. On its kilometer-long sea promenade towards Miramare Castle there are cafes and restaurants. On this urban beach area, many locals spend their free time sunbathing, swimming and doing sports.

Culture

Trieste has a lively cultural scene with various theatres. Among these are the Opera Teatro Lirico Giuseppe Verdi, Politeama Rossetti, the Teatro La Contrada, the Slovene theatre in Trieste (Slovensko stalno gledališče, since 1902), Teatro Miela, and several smaller ones.

The literary-intellectual center of Trieste was or is the existing “Libreria Antiquaria Umberto Saba” corner Via Dante Alighieri in the house Via San Nicolo No. 30, in which James Joyce lived, the house Via San Nicolo No. 32, in which the Berlitz School was located where James Joyce taught and came in contact with Italo Svevo, and the house at Via San Nicolo No. 31, where Umberto Saba spent his breaks in the former cafe-milk shop Walter. In this area, at the end of Via San Nicolo, there is now a life-size statue of Umberto Saba.

There are also numerous museums. Among these are:

- Diego de Henriquez war museum

- Museo Sartorio

- Revoltella Museum modern art gallery

- Civico Museo di Storia Naturale di Trieste (natural history museum) containing fossils of early man.

- Civico Orto Botanico di Trieste, a municipal botanical garden

- Orto Botanico dell'Università di Trieste, the University of Trieste's botanical garden

Two important national monuments:

- The Risiera di San Sabba (Risiera di San Sabba Museum)', a National monument commemorating the holocaust genocide. It was the only Nazi concentration camp with crematorium in Italy.

- The Foiba di Basovizza, a National monument. It is a reminder of the killings of Italians (and other ethnic groups) by Yugoslav partisans after World War II, the last episode of an interethnic violence begun in the 19th century, with the rise of nationalism, and heavily intensified by the Fascist government.

The Slovenska gospodarsko-kulturna zveza—Unione Economica-Culturale Slovena is the umbrella organization bringing together cultural and economic associations belonging to the Slovene minority.

Popular power metal band Rhapsody was founded in Trieste by the city's natives Luca Turilli and Alex Staropoli.

Media

- Newspapers

- Broadcasting

- Television

- RAI Friuli Venezia-Giulia

- Tele Quattro

- Radio

- Radioattività Trieste

- Radio Fragola

- Radio Punto Zero

- Publishing

- Asterios Editore

- Lint Editoriale

Education

The University of Trieste, founded in 1924, is a medium-size state-supported institution with 12 faculties, and boasts a wide and almost complete range of courses. It currently has about 23,000 students enrolled and 1,000 professors. Trieste also hosts the Scuola Internazionale Superiore di Studi Avanzati (SISSA), a leading graduate and postgraduate teaching and research institution in the study of mathematics, theoretical physics, and neuroscience, and the MIB School of Management Trieste, one of Italy's top-five business schools.

There are three international schools offering primary and secondary education programs in English in the greater metropolitan area: the International School of Trieste, the European School of Trieste, and the United World College of the Adriatic. Liceo scientifico statale "France Prešeren", and Liceo Anton Martin Slomšek offer public secondary education in the Slovene language.

The city also hosts numerous national and international scientific research institutions. Among these: AREA Science Park, which comprises ELETTRA, a synchrotron particle accelerator with free-electron laser capabilities for research and industrial applications; the International Centre for Theoretical Physics, which operates under a tripartite agreement among the Italian Government, UNESCO, and International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA); the Trieste Astronomical Observatory; the Istituto Nazionale di Oceanografia e Geofisica Sperimentale (OGS), which carries out research on oceans and geophysics; the International Centre for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology, a United Nations centre of excellence for research and training in genetic engineering and biotechnology for the benefit of developing countries; ICS-UNIDO, a UNIDO research centre in the areas of renewable energies, biofuels, medicinal plants, food safety and sustainable development; the Carso Center for Advanced Research in Space Optics; and the secretariats of The World Academy of Sciences (TWAS) and of the InterAcademy Panel: The Global Network of Science Academies (IAP).

Sports

The local calcio (football) club in Trieste is Triestina, one of the oldest clubs in Italy. Notably, Triestina was runner-up in the 1947/1948 season of the Italian first division (Serie A), losing the championship to Torino.

Trieste is notable for having had two football clubs participating in the championships of two different nations at the same time during the period of the Free Territory of Trieste, due to the schism within the city and region created by the post-war demarcation. Triestina played in the Italian first division (Serie A). Although it faced relegation after the first season after the Second World War, the FIGC changed the rules to keep it in, as it was seen as important to keep a club of the city in the Italian league, while Yugoslavia had its eye on the city. In the championship of next season the club played its best season with a 3rd-place finish. Meanwhile, Yugoslavia bought A.S.D. Ponziana, a small team in Trieste, which under a new name, Amatori Ponziana Trst, played in the Yugoslavian league for 3 years.[62] Triestina went bankrupt in the 1990s, but after being re-founded regained a position in the Italian second division (Serie B) in 2002. Ponziana was renamed as "Circolo Sportivo Ponziana 1912" and currently plays in Friuli-Venezia Giulia Group of Promozione, which is the 7th level of the Italian league.

Trieste also has a well-known basketball team, Pallacanestro Trieste, which reached its zenith in the 1990s under coach Bogdan Tanjević when, with large financial backing from sponsors Stefanel, it was able to sign players such as Dejan Bodiroga, Fernando Gentile and Gregor Fučka, all stars of European basketball. At the end of the 2017–18 season, the team, now trained by coach Eugenio Dalmasson and sponsored by Alma, won promotion to the Lega Basket Serie A, Italy's highest basketball league, fourteen years after its last tenure.

Many sailing clubs have roots in the city which contribute to Trieste's strong tradition in that sport. The Barcolana regatta, which had its first edition in 1969, is the world's largest sailing race by number of participants.

Local sporting facilities include the Stadio Nereo Rocco, a UEFA-certified stadium with seating capacity of 32,500; the Palatrieste, an indoor sporting arena sitting 7,000 people, and Piscina Bruno Bianchi, a large olympic size swimming pool.

Film

Trieste has been portrayed on screen a number of times, with films often shot on location in the area. In 1942 the early neorealist Alfa Tau! was filmed partly in the city.

Cinematic interest in Trieste peaked during the height of the "Free Territory" era between 1947 and 1954 with international films such as Sleeping Car to Trieste and Diplomatic Courier portraying it as a hotbed of espionage. These films, and the later The Yellow Rolls-Royce (1964) conveyed an impression of the city as a cosmopolitan place of conflict between Great Powers, a portrayal which resembled that of Casablanca (1943). Italian filmmakers, by contrast, portrayed Trieste as unquestionably Italian in a series of patriotic films including Trieste mia! and Ombre su Trieste.[63]

The city hosted in 1963 the first International Festival of Science Fiction Film (Festival internazionale del film di fantascienza), which ran until 1982. Under the name Science Plus Fiction (now Trieste Science+Fiction Festival), the festival was brought back in 2000.[64][65]

Recently a new interest in the city sparked with Italian movies such as The Invisible Boy (2014), its sequel The Invisible Boy—Second Generation and Italian TV series.[66]

Transport

Maritime transport

Trieste's maritime location and its former long term status as part of the Austrian and, between 1867–1918, Austro-Hungarian empires made the Port of Trieste the major commercial port for much of the landlocked areas of central Europe. In the 19th century, a new port district known as the Porto Nuovo was built northeast to the city centre.[67]

There is significant commercial shipping to the container terminal, steel works and oil terminal, all located to the south of the city centre. After many years of stagnation, a change in the leadership placed the port on a steady growth path, recording a 40% increase in shipping traffic as of 2007.[67]

Today the port of Trieste is one of the largest Italian ports and next to Gioia Tauro the only deep water port in the central Mediterranean for seventh generation container ships.[68]

Rail transport

Railways came early to Trieste, due to the importance of its port and the need to transport people and goods inland. The first railroad line to reach Trieste was the Südbahn, launched by the Austrian government in 1857. This railway stretches for 1,400 km (870 mi) to Lviv, Ukraine, via Ljubljana, Slovenia; Sopron, Hungary; Vienna, Austria; and Kraków, Poland, crossing the backbone of the Alps mountains through the Semmering Pass near Graz. It approaches Trieste through the village of Villa Opicina, a few kilometres from the big city but over 300 metres (984 feet) higher in elevation. Due to this, the line takes a 32 kilometres (20 miles) detour to the north, gradually descending before terminating at the Trieste Centrale railway station.

In 1887, the Imperial Royal Austrian State Railways (German: kaiserlich-königliche österreichische Staatsbahnen) opened a new railway line, the Trieste–Hrpelje railway (German: Hrpelje-Bahn), from the new port of Trieste to Hrpelje-Kozina, on the Istrian railway.[69] The intended function of the new line was to reduce the Austrian Empire's dependence on the Südbahn network.[70] Its opening gave Trieste a second station south of the original one, which was named Trieste Sant'Andrea (German: Triest Sankt Andrea). The two stations were connected by a railway line that in the initial plans had to be an interim solution: the Rive railway (German: Rive-Bahn), but which survived until 1981, when it was replaced by the Galleria di Circonvallazione, a 5.7-kilometre (3.5 mi) railway tunnel route to the east of the city.

With the opening of the Transalpina Railway from Vienna, Austria via Jesenice and Nova Gorica in 1906, the St Andrea station was replaced by a new, more capacious, facility, named Trieste stazione dello Stato (German: Triest Staatsbahnhof), later Trieste Campo Marzio, now a railway museum, and the original station came to be identified as Trieste stazione della Meridionale or Trieste Meridionale (German: Triest Südbahnhof). This railway also approached Trieste via Villa Opicina, but it took a rather shorter loop southwards towards the sea front. Freight services from the dock area include container services to northern Italy and to Budapest, Hungary, together with rolling highway services to Salzburg, Austria and Frankfurt, Germany.

There are direct intercity and high-speed trains between Trieste and Venice, Verona, Turin, Milan, Rome, Florence, Naples and Bologna. The Mestre railway hub offers further connecting options with high-speed trains to Rome and Milan. Passenger trains also run between Villa Opicina and Ljubljana.

Air transport

Trieste is served by the Trieste – Friuli Venezia Giulia Airport (IATA: TRS). The airport serves domestic and international destinations and is fully connected to the national railway and highway networks. The Trieste Airport railway station links the passenger terminal directly to the Venice–Trieste railway thanks to a 425-meter long skybridge. A 16 platform bus terminal, a multistorey car park with 500 lots and a car park with 1000 lots give public and private motor vehicles rapid access to the A4 Trieste-Turin highway. At the interchange near Palmanova, the A4 branches off to Autostrada A23 linking to Austria's Süd Autobahn (A2) via Udine and Tarvisio. In the southern direction, this highway also offers seamless interconnection to Slovenia's A1 Motorway, and through that to highway networks in Croatia, Hungary, and the Balkans.

Local transport

Local public transport is operated by Trieste Trasporti, which operates a network of around 60 bus routes and two boat services. They also operate the Opicina Tramway, a hybrid between a tramway and funicular railway, providing a more direct link between the city centre and Opicina.[71] However, this tram network has been out of service for at least a year.[72] Works on reopening the line, however, are said to be starting in the near future.

Public Transportation Statistics

The average amount of time people spend commuting with public transit in Trieste e Gorizia, for example to and from work, on a weekday is 49 min. 10% of public transit riders, ride for more than 2 hours every day. The average amount of time people wait at a stop or station for public transit is 11 min, while 18% of riders wait for over 20 minutes on average every day. The average distance people usually ride in a single trip with public transit is 4.6 km, while 6% travel for over 12 km in a single direction.[73]

Notable people

International relations

Trieste hosts the Secretariat of the Central European Initiative, an intergovernmental organization among Central and South-Eastern European states.

In recent years, Trieste was chosen to host a number of high level bilateral and multilateral meetings such as: the Western Balkans Summit in 2017; the Italo-Russian Bilateral Summit in 2013 (Letta-Putin) and the Italo-German Bilateral Summit in 2008 (Berlusconi-Merkel); the G8 meetings of Foreign Affairs and Environment Ministers respectively in 2009 and 2001.

In July 2017, Trieste was selected by Euroscience as the European Science Capital for 2020.

Sister cities and twin towns

Trieste is twinned with:

See also

- Abdus Salam International Centre for Theoretical Physics (ICTP)

- Bathyscaphe Trieste, Swiss-designed, Italian-built deep sea exploration vehicle

- INFN (National Institute of Nuclear Physics)

- International School for Advanced Studies (SISSA)

- People from Trieste

- Teatro Comunale Giuseppe Verdi

- Treaty of peace with Italy (1947)

Notes

- In the beginning called the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, renamed Yugoslavia in 1929.

References

- "Superficie di Comuni Province e Regioni italiane al 9 ottobre 2011". Istat. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- "Total Resident Population on 1st January 2018 by sex and marital status. Province: Trieste". National Institute of Statistics (Italy). Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- "Trieste". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved September 21, 2012.; "Trieste". Lexico UK Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved August 1, 2019.

- "Small Packages - The Forecast 2020" in Monocle (1/2020), pp. 51–66.

- Baldi, Philip (1983). An introduction to the Indo-European languages. SIU Press. p. 168. ISBN 978-0-8093-1091-3. Retrieved 6 December 2010.

- Cary, Joseph (1993-11-15). A ghost in Trieste. University of Chicago Press. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-226-09528-8. Retrieved 6 December 2010.

- Vasmer, Max (1971). Schriften zur slavischen Altertumskunde und Namenkunde. In Kommission bei O. Harrassowitz. p. 50. ISBN 978-3-447-00781-8. Retrieved 6 December 2010.

- "Climate in Trieste". AmbiWeb GmbH. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- Roberto Pedemonte (May 2012). "La neve sulle coste del Maditerraneo (seconda parte)". Rivista Ligure (in Italian). Genova. 12 (44). Retrieved 28 June 2014.

- "Bora and Ice". The Trieste Times. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- Spezialortsrepertorium der österreichischen Länder. Bearbeitet auf Grund der Ergebnisse der Volkszählung vom 31. Dezember 1910, vol. 7: Österreichisch-Illyrisches Küstenland. Vienna: K. k. Hof- und Staatsdruckerei. 1918. pp. 1, 3.

- Giulipaola Ruaro, Strolling Around Trieste, (Trieste: Edizioni Fachin, 1986), 6

- Zeno Saracino: “Pompei in miniatura”: la storia di “Vallicula” o Barcola. In: Trieste All News. 29 September 2018.

- Thaller, Anja (2009). "Graz 1382 – Ein Wendepunkt der Triestiner Geschichte?". Historisches Jahrbuch der Stadt Graz (in German). 38/39: 191–221. Retrieved 6 May 2016.

- Giulipaola Ruaro, Strolling Around Trieste, (Trieste: Edizioni Fachin, 1986), 11

- Perišić, Miroslav; Reljić, Jelica (2016). Kultura Srba u Trstu. Belgrade: Arhiv Srbije.

- Hubmann, Franz, & Wheatcroft, Andrew (editor), The Habsburg Empire, 1840–1916, London, 1972, ISBN 0-7100-7230-9

- Josef Schmidlin, Papstgeschichte der neueren Zeit, München, 1934, p.414

- Hehn, Paul N. (2005) A Low Dishonest Decade: Italy, the Powers and Eastern Europe, 1918–1939., Chapter 2, Mussolini, Prisoner of the Mediterranean

- Morton, Graeme; R. J. Morris; B. M. A. de Vries (2006).Civil Society, Associations, and Urban Places: Class, Nation, and Culture in Nineteenth-century Europe, Ashgate Publishing, UK

- Regio decreto legge 10 Gennaio 1926, n. 17: Restituzione in forma italiana dei cognomi delle famiglie della provincia di Trento

- Mezulić, Hrvoje; R. Jelić (2005). Fascism, baptiser and scorcher (O Talijanskoj upravi u Istri i Dalmaciji 1918–1943.: nasilno potalijančivanje prezimena, imena i mjesta). Zagreb: Dom i svijet. ISBN 953-238-012-4.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Cresciani, Gianfranco (2004) Clash of civilisations, Italian Historical Society Journal, Vol. 12, No. 2, p. 4

- Pizzi, Marco (2017). Nameless. Europa Edizioni. ISBN 9788893841061.

- Angelo Ara, Claudio Magris. Trieste. Un'identità di frontiera. p.38

- Angelo Ara, Claudio Magris. Trieste. Un'identità di frontiera. p.56

- "La storia, parte 10". triestebraica.it. 2007-01-15. Archived from the original on 2012-09-13. Retrieved 2011-09-15.

- Corsellis, John; Marcus Ferrar (2005). Slovenia 1945: Memories of Death and Survival After World War II, I.B.Tauris, ISBN 1-85043-840-4

- Biografia di una bomba

- Così il 10 giugno ’44 Trieste si svegliò sotto le bombe

- Ricordo del bombardamento di San Giacomo: 10 giugno 1944-2019

- 10 giugno 1944: bombe su Trieste

- "Faenza, Trieste and home – the Italian campaign | NZHistory, New Zealand history online". Nzhistory.net.nz. 2012-12-20. Retrieved 2013-03-12.

- Kay, Robin. "IV: Through the Venetian Line". NZETC. Retrieved 2013-03-12.

- Anna Bramwell (1988). Refugees in the Age of Total War. Unwin Hyman. p. 138. ISBN 978-0-04-445194-5. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- Petacco, Arrigo (2005). Tragedy Revealed: The Story of Italians from Istria, Dalmatia, and Venezia Giulia, 1943–1956. University of Toronto Press. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-8020-3921-7. Retrieved 29 December 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Petacco 2005, p. 90.

- Feis, Herbert (2015). Between War and Peace. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 282.

- Cox, Geoffrey (1977). The Race for Trieste. London: W. Kimber. p. 250.

- "The Current Situation in the Free Territory of Trieste" (PDF). CIA. 1948. Retrieved 21 June 2014.

- "British Element Trieste Forces – Order of Battle". Retrieved 21 June 2014.

- "La Cantieristica Triestina" [Trieste naval industries] (in Italian). Archived from the original on 6 March 2012. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- "Ministry of Foreign Affairs – Europe – Infrastructure Networks". Esteri.it. 2000-07-07. Retrieved 2010-04-19.

- "The company in figures". Retrieved 16 September 2015.

- "Geography and Economy — ICTP Portal". Infopoint.ictp.it. Retrieved 2010-04-19.

- "Trieste Coffee Cluster". Archived from the original on 23 January 2012. Retrieved 16 September 2015.

- "Demo-Geodemo. – Mappe, Popolazione, Statistiche Demografiche dell'ISTAT". Retrieved 16 September 2015.

- "Il censimento del 1921". Retrieved 16 September 2015.

- "Il censimento del 1961". Retrieved 16 September 2015.

- "Il censimento del 1981". Retrieved 16 September 2015.

- "Kad je Trst bio naš: Evo koje srpske porodice su živele u ovom gradu i to u najlepšim vilama (FOTO)". Telegraf.rs (in Serbian). Retrieved 2019-12-30.

- "Trieste: In the wake of James Joyce". Jason Cowley. 2000-06-25. Retrieved 2010-04-19.

- "Socio-demographic Overview of Immigrants and Immigrant Children in Italy" (PDF).

- "Cittadini Stranieri – Trieste 2018". tuttitalia.it. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- Stranj, Pavel, Slovensko prebivalstvo Furlanije-Julijske krajine v družbeni in zgodovinski perspektivi, Trst, 1999

- Spezialortsrepertorium der Oesterreichischen Laender. VII. Oesterreichisch-Illyrisches Kuestenland. Wien, 1918, Verlag der K.K. Hof- und Staatsdruckerei

- The 1911 census

- Pavel Stranj, La comunità sommersa, Založba tržaškega tiska, Trieste/Trst 1992

- "Jason Cowley". Jason Cowley. 2000-06-25. Retrieved 2009-06-18.

- Lonely Planet (14 May 2012). "10 of the world's unsung places". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 16 September 2015.

- Frothingham, A. L. (1904). "A Revised List of Roman Memorial and Triumphal Arches". American Journal of Archaeology. 8 (1): 1–34. doi:10.2307/497017. JSTOR 497017.

- Calcio. Harper Perennial. ASIN 0007175744.

- Pizzi, Katia. A City in Search of an Author. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2001. p.61-62

- "Trieste Science+Fiction – Festival della Fantascienza » FIFF 1963". Retrieved 16 September 2015.

- "Trieste International Film Festival". Retrieved 16 September 2015.

- "Set porta rossa a Trieste".

- Ammann, Christian; Juvanec, Maj (May 2007). "Discovering Trieste". Today's Railways. Platform 5 Publishing Ltd. pp. 29–31.

- Andreas Deutsch: Verlagerungseffekte im containerbasierten Hinterlandverkehr. University of Bamberg Press, 2014, ISBN 978-3-86309-160-6, p 143.

- Alessandro Tuzza; et al. "Prospetto cronologico dei tratti di ferrovia aperti all'esercizio dal 1839 al 31 dicembre 1926" [Chronological overview of the features of the railways opened between 1839 and 31 December 1926]. www.trenidicarta.it (in Italian). Alessandro Tuzza. Retrieved 17 December 2010.

- Oberegger, Elmar. "Hrpelje-Bahn" [Hrpelje Railway] (in German). Part of this series: Zur Eisenbahngeschichte des Alpen-Donau-Adria-Raumes. Oberegger, Elmar. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 7 March 2011.

- "Trieste Trasporti S.p.A." Trieste Trasporti S.p.A. Retrieved April 27, 2007.

- https://www.triesteprima.it/cronaca/tram-opicina-linea-commissione-25-ottobre-2018.html

- "Trieste e Gorizia Public Transportation Statistics". Global Public Transit Index by Moovit. Retrieved June 19, 2017.

- "Twin Towns – Graz Online – English Version". www.graz.at. Archived from the original on 2009-11-08. Retrieved 2010-01-05.

External links

- Municipality of Trieste (in Italian)

- Trieste Chamber of Commerce (in Italian)

- University Of Trieste

- Trieste City of Science

- Grotta Gigante official site (in Italian)

- Porto.trieste.it (in Italian)

- Trieste – Photo Guide – (in Italian) – (pdf)

- Giovanni Maria Cassini (1791). "Lo Stato Veneto da terra diviso nelle sue provincie, seconda parte che comprede porzioni del Dogado del Trevisano del Friuli e dell' Istria". Rome: Calcografia camerale. (Map of Trieste region).

- Color footage of Trieste in the 1960s (1963) from British Pathé at YouTube