Supermax prison

A super-maximum security (supermax) or administrative maximum (ADX) prison is a "control-unit" prison, or a unit within prisons, which represents the most secure levels of custody in the prison systems of certain countries. The objective is to provide long-term, segregated housing for inmates classified as the highest security risks in the prison system (the "worst of the worst" criminals) and those who pose an extremely serious threat to both national and global security.[1]

Characteristics and practices

According to the National Institute of Corrections, an agency of the United States government, "a supermax is a stand-alone unit or part of another facility and is designated for violent or disruptive inmates. It typically involves up to 23-hour-per-day, single-cell confinement for an indefinite period of time. Inmates in supermax housing have minimal contact with staff and other inmates," a definition confirmed by a majority of prison wardens.[2]

Leena Kurki and Norval Morris have argued there is no absolute definition of a supermax and that different jurisdictions classify prisons as supermax inconsistently. They identify four general features that tend to characterize supermax prisons:[3]

- Long-term: once transferred to a supermax prison, prisoners tend to stay there for several years or indefinitely.

- Powerful administration: supermax administrators and correctional officers have ample authority to punish and manage inmates, without outside review or prisoner grievance systems.

- Solitary confinement: supermax prisons rely heavily on intensive (and long-term) solitary confinement, which is used to isolate and punish prisoners as well as to protect them from themselves and each other. Communication with outsiders is minimal to none.

- Very limited activities: few opportunities are provided for recreation, education, substance abuse programs, or other activities generally considered healthy and rehabilitative at other prisons.

Prisoners are placed not as a punishment of their crimes but by their previous history when incarcerated or based on reliable evidence of an impending disruption. For example, this could be a prisoner who is a gang leader or planning a radical movement. These decisions are made as administrative protection measures and the prisoners in a supermax are deemed by correctional workers as a threat to the safety and security of the institution itself.[3]

The amount of inmate programming varies from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. Certain jurisdictions provide entertainment for their inmates in the form of television, educational and self-help programs. Others provide instructors who speak to inmates through the cell door. Some jurisdictions provide no programming to its inmates.[3] In a supermax, prisoners are generally allowed out of their cells for only one hour a day (one-and-a-half hours in California state prisons). Exercise is done in indoor spaces or small, secure, outdoor spaces, usually alone or in a pair and always watched by the guard. Group exercise is offered only to those who are in transition programs.

Inmates receive their meals through ports in the doors of their cells.[4]

Prisoners are under constant surveillance, usually with closed-circuit television cameras. Cell doors are usually opaque, while the cells may be windowless. Furnishings are plain, with poured concrete or metal furniture common. Cell walls, and sometimes plumbing, may be soundproofed to prevent communication between the inmates.[4]

History

Australia

An early form of supermax-style prison unit appeared in Australia in 1975, when "Katingal" was built inside the Long Bay Correctional Centre in Sydney. Dubbed the "electronic zoo" by inmates, Katingal was a super-maximum security prison block with 40 prison cells having electronically operated doors, surveillance cameras, and no windows. It was closed down two years later over human rights concerns.[5] Since then, some maximum-security prisons have gone to full lockdown as well, while others have been built and dedicated to the supermax standard.

In September 2001, the Australian state of New South Wales opened a facility in the Goulburn Correctional Centre to the supermax standard. While its condition is an improvement over that of Katingal of the 1970s, this new facility is nonetheless designed on the same principle of sensory deprivation.[6][7] It has been set up for 'AA' prisoners who have been deemed a risk to public safety and the instruments of government and civil order or are believed to be beyond rehabilitation. Corrections Victoria in the state of Victoria also operates the Acacia and Melaleuca units at Barwon Prison which serve to hold the prisoners requiring the highest security in that state including Melbourne Gangland figures such as Tony Mokbel, and Carl Williams, who was murdered in the Acacia unit in 2010.

Brazil

In 1985, the state government of São Paulo created an annex to a psychiatric penitentiary hospital meant to house the most violent inmates of the region and established the Penitentiary of Rehabilitation Center of Taubaté, also known as Piranhão. Previously, high-risk inmates were housed at a prison on Anchieta Island; however, that closed down after a bloody massacre. At Taubaté, inmates spent 23 hours of a day in solitary confinement and spent 30 minutes a day with a small group of seven to ten inmates. Ill-treatment of inmates occurred on a daily basis, causing major psychological impairment.[8]

Throughout the 1990s, and the early-2000s, Brazil faced major challenges with gang structures within its prisons. The gang Primeiro Comando da Capital (PCC) gained notoriety in the prison system and had new members joining within the prisons. Riots were a common occurrence and the gang culture became uncontrollable, leading authorities to pass the controversial Regime Disciplinar Diferenciado (RDD), a culture founded from disciplinary punishment.[9]

United Kingdom

Britain's Her Majesty's Prison Service in England and Wales has had a long history in controlling prisoners that are high-risk. Prisoners are categorized into four main classifications (A, B, C, D) with A being "highly dangerous" with a high risk of escaping to category D in which inmates "can be reasonably trusted in open conditions."[10]

The British government formed the Control Review Committee in 1984 to allow for regulating long-term disruptive prisoners. The committee proposed special units (called CRC units) which were formally introduced in 1989 to control for highly-disruptive prisoners to be successfully reintegrated. Yet a series of escapes, riots, and investigations by authorities saw the units come to a close in 1998. They would soon be replaced by Close Supervision Centres (CSC), which was meant to provide relief for long-term prisons which are still used in the present day.[11] It was reported to hold 60 of the most dangerous men in the UK in 2015.[12]

United States

The United States Penitentiary Alcatraz Island, opened in 1934, has been considered a prototype and early standard for a supermax prison.[13] Supermax prisons began to proliferate within the United States after 1984. Prior to 1984, only one prison in the U.S. met "supermax" standards: the Federal Penitentiary in Marion, Illinois. By 1999, the United States contained at least 57 supermax facilities, spread across 30–34 states.[3] The push for this type of prison came after two correctional officers at Marion, Merle Clutts, and Robert Hoffman, were stabbed to death in two separate incidents by inmates Thomas Silverstein and Clayton Fountain. This prompted Norman Carlson, director of the Federal Bureau of Prisons, to call for a new type of prison to isolate uncontrollable inmates. In Carlson's view, such a prison was the only way to deal with inmates who "show absolutely no concern for human life".[14]

In recent years a number of U.S. states have downgraded their supermax prisons, as has been done with Wallens Ridge State Prison, a former supermax prison in Big Stone Gap, Virginia. Other supermax prisons that have gained notoriety for their harsh conditions and attendant litigation by inmates and advocates are the former Boscobel (in Wisconsin), now named the Wisconsin Secure Program Facility, Red Onion State Prison (in western Virginia, the twin to Wallens Ridge State Prison), Tamms (in Illinois), and the Ohio State Penitentiary. Placement policies at the Ohio facility were the subject of a U.S. Supreme Court case (Wilkinson v. Austin) in 2005[15] where the Court decided that there had to be some, but only very limited, due process involved in supermax placement.

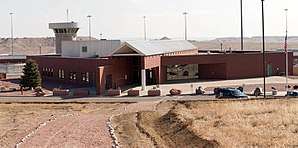

There is only one supermax prison remaining in the United States federal system, ADX Florence in Florence, Colorado.[16] It houses numerous inmates who have a history of violent behavior in other prisons, with the goal of moving them from solitary confinement for up to 23 hours a day to a less restrictive prison within three years. However, it is best known for housing several inmates who have been deemed either too dangerous, too high-profile or too great a national security risk for even a maximum-security prison.[14] Residents have included Timothy McVeigh, perpetrator of the Oklahoma City Bombing who was executed by lethal injection at the Federal Correctional Complex, Terre Haute on 11 June 2001; Terry Nichols, McVeigh's accomplice; Theodore Kaczynski, a domestic terrorist otherwise known as the Unabomber, who once attacked via mail bombs; Robert Hanssen, an American FBI agent turned Soviet spy; Richard Reid, known as the "Shoe Bomber", who was jailed for life for attempting to detonate explosive materials in his shoes while on board an aircraft;[17] Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab, the "Underwear Bomber"; Richard Lee McNair, a persistent prison escapee; Charles Harrelson, a hitman who was convicted in 1979 of killing Federal Judge John H. Wood Jr.;[18] and Vito Rizzuto, boss of the "Sixth Mafia Family", released on 5 October 2012.[19] The Boston Marathon Bomber Dzhokhar Tsarnaev is housed there. Joaquín "El Chapo" Guzmán was also sent here. Deprivation of social contact and the isolation of inmates have some unintended positive and negative effects.

However, many states now have created supermax prisons, either as stand-alone facilities or as secure units within lower-security prisons.[20] State supermax prisons include Pelican Bay in California and Tamms in Illinois. The USP in Marion, Illinois was recently downgraded to a medium-security facility. Some facilities such as California State Prison, Corcoran (COR) are hybrids incorporating a supermax partition, housing or having housed high-security prisoners such as Charles Manson.

Cost-benefit analysis of supermax prisons

There is no set definition of a supermax prison; however, the United States Department of Justice and the National Institute of Corrections agree that "these units have basically the same function: to provide long-term, segregated housing for inmates classified as the highest security risks in a state’s prison system."[21] When making comparisons between supermax prisons and non-supermax prisons, a clear and consistent definition is crucial. As a result, applying one definition to "supermax housing" across all states and jurisdictions is very important. Things to consider include types of prisoners, facility conditions and the purpose of the facility is important to the analysis.[22]

Consequently, it is hard to provide a cost-benefit analysis with varying facilities across the board. In these cases, a cost-benefit analysis would be beneficial in the decision to construct a facility, upgrade an existing facility, or determine whether a facility should be closed down.

Costs of operating a supermax prison

Building a supermax prison, or even retrofitting an old prison, is very expensive. ADX Florence took $60 million to build in 1994.[23] In 2010, when President Obama wanted to transfer Guantanamo Bay detainees to the Thomson Correctional Center, costs were expected to be $237 million to renovate, retrofit, and set up the center.[24]

Compared to a maximum security facility, supermax prisons are extremely expensive to run and can cost about three times more on average.[25] The 1999 average annual cost for inmates at Colorado State Penitentiary, a supermax facility, was $32,383. Compared with the maximum-security prison, the Colorado Correctional Center's annual inmate cost was $18,549.[26] This is mainly due to the technology needed to further maintain a supermax: high-security doors, fortified walls, and sophisticated electronic systems. There are higher costs for staffing these facilities because more people must be hired to maintain the buildings and facilities. These costs are paid by taxpayers and depend on the jurisdiction of the prison. Federal prisons are provided for by federal taxes, while state prisons are provided for by the state.[26]

Furthermore, there are many costs that are harder to measure. Supermax facilities have had a history of psychological and mental health issues to their inmates. These psychological problems present an additional layer of burden to society. Additional costs to society are incurred when inmates have a hard time readjusting to normal life after release, and inmates may even be more inclined to commit even worse offenses to society.

Controversy

Supermax and Security Housing Unit (SHU) prisons are controversial. One criticism is that the living conditions in such facilities violate the United States Constitution, specifically, the Eighth Amendment's proscription against "cruel and unusual" punishments.[27] In 1996, a United Nations team assigned to investigate torture described SHU conditions as "inhuman and degrading".[28] A 2011 New York Bar association comprehensive study suggested that supermax prisons constitute "torture under international law" and "cruel and unusual punishment under the U.S. Constitution".[29] In 2012, a federal class action suit against the Federal Bureau of Prisons and officials who run ADX Florence SHU (Bacote v. Federal Bureau of Prisons, Civil Action 1:12-cv-01570) alleged chronic abuse, failure to properly diagnose prisoners, and neglect of prisoners who are seriously mentally ill. The suit was dismissed.[30]

Prisons with supermax facilities

North America

Canada

- Special Handling Unit (Sainte-Anne-des-Plaines, Quebec) – Houses Canada's most dangerous and violent inmates

Mexico

- Penal del Altiplano – Almoloya de Juarez, State of Mexico. Full Supermax and the only facility of this kind in Mexico.

United States

Most of these facilities only contain supermax wings or sections, with other parts of the facility under lesser security measures.

- Alabama

- Arizona

- Arkansas

- California

- United States Penitentiary – Atwater, California

- Pelican Bay State Prison – Crescent City, California

- United States Penitentiary, Alcatraz Island – San Francisco, California (Closed 21 March 1963)

- California Correctional Institution, Tehachapi, California

- High Desert State Prison – Susanville, California

- Richard J. Donovan Correctional Facility – San Ysidro, California

- Colorado

- Connecticut

- Florida

- Georgia

- Idaho

- Illinois

- United States Penitentiary – Marion, Illinois (Downgraded to a medium-security facility in September 2006)[31]

- Tamms Correctional Center – Tamms, Illinois (Closed January 2013)

- Menard Correctional Center – Chester, Illinois

- Indiana

- Kansas

- United States Disciplinary Barracks – Fort Leavenworth, Kansas (military prison)

- United States Penitentiary – Leavenworth, Kansas (being downgraded to medium security)

- Kentucky

- Kentucky State Penitentiary – Eddyville, Kentucky (the only prison in Kentucky housing supermax units)

- Louisiana

- Louisiana State Penitentiary – West Feliciana Parish, Louisiana

- United States Penitentiary Pollock

- Maine

- Maryland

- Chesapeake Detention Facility – Baltimore, Maryland

- North Branch Correctional Institution – Cumberland, Maryland (final housing unit began operation in summer of 2008)

- Massachusetts

- Minnesota

- Minnesota Correctional Facility Oak Park Heights – Oak Park Heights, Minnesota (Although Oak Park Heights is classified as a Supermax, the majority of inmates are not housed in solitary confinement)[32]

- Mississippi

- Missouri

- Jefferson City Correctional Center – Jefferson City, MissouriPotosi, SECC, SCCC, Chillicothe, etc

- New Hampshire

- New Jersey

- New Jersey State Prison – Trenton, New Jersey

- East Jersey State Prison – Woodbridge, New Jersey

- Northern State Prison – Newark, New Jersey

- Essex County Correctional Facility – Newark, New Jersey

- New Mexico

- Penitentiary of New Mexico – unincorporated Santa Fe County, New Mexico – Uses the Bureau Classification System – Level 6 being Supermax

- New York

- Attica Correctional Facility – Attica, New York

- Upstate Correctional Facility – Malone, New York

- Sing Sing Correctional Facility – Ossining, New York

- Southport Correctional Facility – (disciplinary supermax prison with only solitary confinement), Pine City, New York

- North Carolina

- Polk Correctional Institution – Butner, North Carolina

- Ohio

- Oklahoma

- Oregon

- Pennsylvania

- South Carolina

- Tennessee

- Texas

- United States Penitentiary – Jefferson County, Texas

- Estelle High Security Unit – W.J. Estelle Unit – Walker County, Texas[34]

- Allan B. Polunsky Unit (formerly Terrell Unit) – West Livingston, Texas[35]

- Gib Lewis Unit High Security Expansion Cellblock "super seg" — Woodville, Texas

- Utah

- Virginia

- Washington

- West Virginia

- Mt. Olive Correctional Complex – Fayette County, West Virginia

- Wisconsin

South America

Brazil

In Brazil, the "regime disciplinar diferenciado" (differentiated disciplinary regime), known by the acronym RDD, and strongly based on the Supermax standard, was created primarily to handle inmates who are considered capable of continuing to run their crime syndicate or to order criminal actions from within the prison system, when confined in normal maximum security prisons that allow contact with other inmates. Since its inception, the following prisons were prepared for the housing of RDD inmates:

- Centro de Readaptação Provisória de Presidente Bernardes (Presidente Bernardes, São Paulo, Brazil) – inspired by the supermax standards, although prisoners can only stay there for a maximum of 2 years. Is a part of the prison system of the Brazilian State of São Paulo.

- Penitenciária Federal de Catanduvas (Catanduvas, Paraná, Brazil) – also based on the supermax standards. It is the first federal prison in Brazil, designed to receive prisoners deemed too dangerous to be kept in the states' prison systems (in Brazil, ordinarily, both convicts sentenced by States' courts or by the Federal Judiciary fulfill their prison terms in state-run prisons; the Federal Prison System was created to handle only the most dangerous prisoners in Brazil, such as major drug lords, convicted either by the Federal Judiciary or by the judiciary of a state).

- Penitenciária Federal de Campo Grande (Campo Grande, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil) – the second of two Brazilian Federal prisons based on the supermax specifications.

Colombia

- Penitenciaría de Cómbita (Colombia) – follows supermax specifications, hosts terrorists and drug lords.

- Establecimiento Penitenciario de Alta y Mediana Seguridad de Girón EPAMSGIRON.

Europe

- Leopoldov Prison – (Leopoldov, Slovakia) a 17th-century fortress built against Ottoman Turks that was converted into a high-security prison

- Portlaoise Prison (Portlaoise, Ireland) – One of the most secure prisons in Europe, protected full time by members of the Irish Defence Forces. Held many convicted IRA prisoners.

- Nieuw Vosseveld – Dutch High Security prison in Vught

- Stammheim Prison – German High Security Prison, partly purpose-built to keep Red Army Faction terrorists in the 1970s and 1980s.

- Politigårdens Fængsel – (Copenhagen – Denmark) There are 25 maximum security cells located in the prison of the central police station of Copenhagen

- The State Prison of East Jutland – (Horsens – Denmark) – High Security Prison. Holds many of Denmark's most dangerous criminals.

- Penal colony № 6 Federal Penitentiary Service – Sol-Iletsk – Russia – correctional facility in Sol-Iletsk, Orenburg Oblast, Russia.

- Kumla Prison, Hall Prison, and Saltvik Prison – Sweden – All three prisons have a similar security unit called Fenix, which can house 24 inmates.

- Sassari District Prison "Giovanni Bacchiddu" at Bancali, Sardinia (Italy). Housing about 90 super-high security criminals all subject to the provisions of the Article 41-bis prison regime, detained in self-contained sections, each with 4 cells, a small courtyard and a video-conference room where they can be interrogated and undergo trials without leaving the prison. This specially-designed supermax has been built to replace the old maximum-security prison of the Asinara island, the so-called "Italian Alcatraz", that was closed in 2002.[36]

United Kingdom

- Belmarsh – London, England, United Kingdom – many of the terrorists of the 2006 transatlantic aircraft plot are imprisoned there.

- Frankland – Durham, England, United Kingdom – High Security Prison with a special unit for prisoners suffering from Dangerous and Severe Personality Disorders.

- Full Sutton – York, England, United Kingdom – High Security Prison.

- Long Lartin – Worcestershire, England, United Kingdom – High Security Prison.

- Maghaberry – Lisburn, Northern Ireland, United Kingdom – High Security Prison

- Manchester – Strangeways, Manchester, England, United Kingdom – High Security Prison with a special unit for prisoners suffering from Dangerous and Severe Personality Disorders.

- Prison Shotts – Shotts, Scotland, United Kingdom – High Security Prison. Holds some of the UK's most dangerous and violent criminals.

- Whitemoor – March, Cambridgeshire, England, United Kingdom – houses up to 500 of the most dangerous criminals in the UK. It has a unit known as the 'Close Supervision Centre' which is referred to as a "Prison inside a Prison". It has a special unit for prisoners with Dangerous and Severe Personality Disorders.

- Wakefield – Wakefield, England, United Kingdom – High Security Prison with a 'Close Supervision Centre'. It is nicknamed "The Monster Mansion" due to the many high-profile convicted murderers incarcerated there.

- Woodhill – Milton Keynes, England, United Kingdom – High Security Prison with a specialist 'Close Supervision Centre'.

Africa

- C Max (Pretoria, South Africa) – for violent and disruptive prisoners.

- Scorpion prison (Cairo, Egypt) – Supermax prison located inside the Tora Prison complex.

Asia

- Gyeongbuk Northern the Second Correctional Center(Prison), Cheongsong, Gyeongsangbuk-do, South Korea

- KEMTA, Taiping, Perak Malaysia

- Al Hayer Prison (Riyadh, Saudi Arabia)

- Bilibid Prison (Manila, Philippines) – Large maximum security prison with around 17,000–20,000 convicted prisoners.[37]

- Nusa Kambangan Correctional Facility, Central Java, Indonesia – Supermax prison built during the Dutch era, now under the jurisdiction of Ministry of Law and Human Rights

- Black Dolphin – Russian maximum-security prison for convicts sentenced to life imprisonment.

- White Swan – Russian maximum-security prison for convicts sentenced to life imprisonment.

- Al-Muwaqqar II Correctional and Rehabilitation Center is a super-maximum security prison with 240 cells in Jordan, see also Correction centers in Jordan. It is designed to hold incorrigibly violent inmates in separate isolation cells.

- Khao Bin Central Prison, Ratchaburi, Thailand – Supermax facility being opened in the first half of 2014.[38]

Australia

- Goulburn Correctional Centre – Full Supermax prison, the highest level of security in Australia – 75-bed centre, (Goulburn, New South Wales).[6]

- Casuarina Prison – Special Handling Unit (SHU) (Perth, Western Australia)

- Her Majesty's Prison Risdon – 8 cell Tamar Unit (Risdon Vale, Tasmania)

- Her Majesty's Prison Barwon – Barwon Supermax (Lara, Victoria)

- Port Phillip Prison – Charlotte unit (Truganina, Victoria)

- Brisbane Correctional Centre – 18-cell Maximum Security Unit (Brisbane, Queensland)

- Alexander Maconochie Centre – 12-cell Supermax Section (Hume, Australian Capital Territory)

- Yatala Labour Prison – G Division (Northfield, South Australia)

- Alice Springs Correctional Centre – 12-cell Supermax Unit (Alice Springs, Northern Territory)

Popular media

The movie Escape Plan starring Sylvester Stallone, Arnold Schwarzenegger, and Jim Caviezel is based on an ocean-based "supermax facility".

In various Marvel Comics, "The Raft" is the name of a Supermax prison located near Ryker's Island designed to hold the most dangerous heroes and villains. It subsequently is mentioned in and appears in the Marvel Cinematic Universe, albeit amended to appear as a floating fully submersible prison.

See also

- List of prisons

- Penology

- Panopticon

- Solitary confinement

- Incarceration in the United States (security levels)

- Article 41-bis prison regime the Italian high security treatment for Mafiosi and terrorists

- Prisoner security categories in the United Kingdom

- F-type Prisons (Turkey)

- Black Dolphin Prison

References

- Mears, Daniel. "Evaluating the Effectiveness of Supermax Prisons" (PDF). Urban Institute – Justice Policy Center. Retrieved 16 May 2012.

- Daniel P. Mears, "Evaluating the Effectiveness of Supermax Prisons", Urban Institute, March 2006.

- Leena Kurki and Norval Morris, "The Purposes, Practices, and Problems of Supermax Prisons", Crime and Justice 28, 2001; accessed via JStor.

- Shalev, S. (2009) Supermax: controlling risk by solitary confinement. Cullompton: Willan Publishing.

- Kennedy, Les (19 May 2004). "Final release for Katingal, misguided experiment in extreme jails". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 5 January 2012.

- Masters, Chris (17 November 2005). "SuperMax". Four Corners. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- Watson, Rhett (9 May 2009). "Inside the walls of SuperMax prison, Goulburn". The Daily Telegraph. Australia. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- Ross, Jeffrey Ian; de Jesus Filho, José (2013). "The Rise of the Supermax in Brazil". The globalization of supermax prisons. Rutgers University Press. pp. 130–132. ISBN 9780813557410. OCLC 784708328.

- Ross, Jeffrey Ian; de Jesus Filho, José (2013). "The Rise of the Supermax in Brazil". The globalization of supermax prisons. Rutgers University Press. pp. 130–135. ISBN 9780813557410. OCLC 784708328.

- Ross, Jeffrey Ian; West Crew, Angela West (2013). "The Growth of the Supermax Option in Britain". The globalization of supermax prisons. Rutgers University Press. pp. 51–60. ISBN 9780813557410. OCLC 784708328.

- Ross, Jeffrey Ian; Crew, Angela West (2013). "The Growth of the Supermax Option in Britain". The globalization of supermax prisons. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 9780813557410. OCLC 784708328.

- "Close Supervision Centres – a well run system which contains dangerous men safely and decently". www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- Carlson, Peter M.; Garrett, Judith Simon, Prison and Jail Administration: Practice and Theory, Jones and Bartlett Publishers, 1999. Cf. Chapter 35, p.252, "Supermaximum Facilities", by David A. Ward.

- Taylor, Michael (23 June 2011). "The Last Worst Place". The San Francisco Chronicle.

- Wilkinson v. Austin 04-495 (2005), Link to case text

- Vick, Karl (30 September 2007). "Isolating the Menace In a Sterile Supermax". Washington Post. pp. A03. Retrieved 21 December 2007.

- "Just how bad are American 'supermax' prisons?". BBC News. 10 April 2012.

- "Woody Harrelson's Father Dies In Prison". cbsnews.com. 21 March 2007. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- Template:Montreal Gazette

- Riveland, C. (1999) Supermax prisons: overview and general considerations. Washington D.C.: U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute of Corrections

- U.S. Department of Justice; National Institute of Corrections. "Supermax Prisons and the Constitution" (PDF).

- Lawrence, Sarah (2004). "Benefit-Cost Analysis of Supermax Prisons: Critical Steps and Considerations". Urban Institute Justice Policy Center.

- Binelli, Mark (26 March 2015). "Inside America's Toughest Federal Prison". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- "Obama budget includes money to house Guantanamo detainees in U.S. - CNN.com". www.cnn.com. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- Mears, Daniel P. "Evaluating the Effectiveness of Super max Prisons." PsycEXTRA Dataset (2006): n. pag. NCJRS, Jan. 2006. Web. 22 November 2015.

- Pizarro, Jesenia; Stenius, Vanja M. K. (June 2004). "Supermax Prisons: Their Rise, Current Practices, and Effect on Inmates". The Prison Journal. 84: 254–260.

- PrisonActivist.org – California's Security Housing Units. Archived 10 October 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- Paglen.com Archived 11 April 2006 at the Wayback Machine – Security Housing Unit

- – The Brutality of Supermax Confinement

- Cohen, Andrew (18 June 2012) An American Gulag: Descending into Madness at Supermax The Atlantic, Retrieved 20 June 2012

- "USP Marion". bop.gov. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- "Inside Maximum Security". Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- "George Bell III Transferred from Parchman." WLBT. 18 August 2008. Retrieved on 10 August 2010.

- Ward, Mike. "Hunt is on for escaped killer." Austin American-Statesman. 29 June 1999. A1. Retrieved on 27 November 2010. "Clifford Dwayne Jones' escape from the Estelle High-Security Unit on Sunday afternoon was the first from a Texas prison this year and the first from the "super max" lockup, as the unit is called."

- Ward, Mike. "Death row inmates free guard, meet with activists." Austin American-Statesman. 23 February 2000. "A prison guard held hostage by two execution-bound killers inside Texas'``super maxdeath row[...]" and "Tuesday deep inside the maximum-security Terrell Unit just outside[...]"

- Abbate, Lirio (2 February 2015). "L'isola dei reclusi: ecco il carcere durissimo (e segreto) per 90 superboss mafiosi". L'Espresso (in Italian). Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- "The Commandos Fact File From Inside The Gangsters' Code on DiscoveryUK.com". discoveryuk.com. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- "Prison troublemakers face 'supermax' unit". The Nation. 30 June 2014. Retrieved 8 March 2015.