Goulburn Correctional Centre

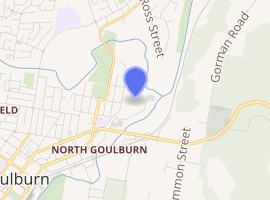

The Goulburn Correctional Centre, an Australian supermaximum security prison for males, is located in Goulburn, New South Wales, three kilometres north-east of the central business district. The facility is operated by Corrective Services NSW, an agency of the Department of Justice, of the Government of New South Wales. The Complex accepts prisoners charged and convicted under New South Wales and/or Commonwealth legislation and serves as a reception prison for Southern New South Wales, and, in some cases, for inmates from the Australian Capital Territory.

The hand-carved sandstone gate and façade of the Goulburn Correctional Centre | |

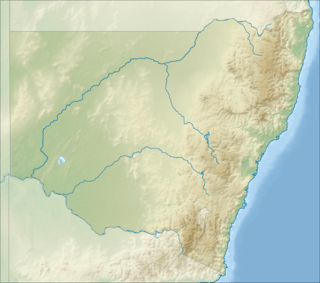

Goulburn Correctional Centre Location in New South Wales | |

| Location | Goulburn, New South Wales, Australia |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 34°44′29″S 149°44′26″E |

| Status | Operational |

| Security class |

|

| Capacity | 222 |

| Opened | 1 July 1884 |

| Former name |

|

| Managed by | Corrective Services NSW |

| Website | Goulburn Correctional Centre |

Building details | |

| |

| General information | |

| Cost |

|

| Technical details | |

| Material | Sandstone and brick |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | James Barnet |

| Architecture firm | Colonial Architect of New South Wales |

| Designated | 1 January 1977 |

| Official name | Goulburn Correctional Centre complex |

| Designated | 2 April 1999 |

| Reference no. | 00808 |

The High Risk Management Centre (commonly called the SuperMax) was opened in September 2001. This was the first such facility in Australia and makes the Centre the highest security prison in Australia.[1] Supermax was completely renovated over 9 months and completed in April 2020.

The current structure incorporates a massive, heritage-listed hand-carved sandstone gate and façade that was opened in 1884 based on designs by the Colonial Architect, James Barnet. The complex is listed on the Register of the National Estate and the New South Wales State Heritage Register as a site of State significance.[2]

History

.jpg)

Goulburn's first lock-up was built around 1830 and gallows were built as early as 1832 when floggings were common.[3] The first Goulburn Gaol was proclaimed on 28 June 1847, attached to the local Courthouse. When the Controller of Prisons first reported to parliament in 1878 Goulburn Gaol had accommodation for 63 segregated and 127 associated prisoners, and held 66 prisoners; inclusive of one female.[4]

The plan for the new prison complex was developed in 1879 as part of a scheme to "bring the Colony from its backward position as regards to prison buildings", in J. Barnet's office under the supervision of William Coles.[5] It was built by Frederick Lemm of Sydney between 1881 and 1884 at a cost of sixty-one thousand pounds. It was formally proclaimed as a public gaol, prison and house of correction from 1 July 1884. The gaol also became a place of detention for male prisoners under sentence or transportation. The new gaol increased the capacity of the gaol to 182 separated and 546 associated prisoners. In the year ended 1884 there were a total of 295 prisoners in custody. The opening of the gaol was part of the public works boom in the town during the 1869- 6 period and boosted employment as well as local industry. In 1893 prison labour was used to build an additional 127 cells to Goulburn Gaol, six exercise yards for 'youthful offenders' and a further yard for prisoners awaiting trial. This extension enabled Goulburn gaol to operate on the principle of restricted association which was gradually being adopted throughout the Colony. The following year additional cells were erected for female prisoners. The '7th class' prisoners were moved into the former women's cells thus preventing contact between these young prisoners and serious offenders. Steam cooking facilities were installed and a 70-foot (21 m) chimney was erected, new workshops were planned to create one of the most complete prison complexes in NSW.[4][6]

Areas for agricultural cultivation were introduced in 1897-1899 and a bakery was constructed in 1916. In 1957 work commenced on a new cell block outside the walls of the gaol to accommodate prisoners employed at the agricultural area. This wing opened in 1961. During 1966-1967 a new education block and auditorium were completed.[7][6]

For eighty years up to the 1970s, Goulburn was the establishment within the NSW penal system with a particular role in the reformation of first time and young offenders. It had a long history of agricultural and industrial training and education and built up a strong economic and social association with the town of Goulburn.[6]

The prison was renamed the Goulburn Reformatory in 1928, and became known as the Goulburn Training Centre in 1949. In 1992 the centre was again renamed - Goulburn Correctional Centre.[4]

In 1986-1988 the first major redevelopment project was undertaken. It involved the extension of the perimeter walls to include a new industrial and sports area and the construction of a high security segregation unit.[8][6]

Initially, Goulburn was one of the principal gaols in NSW. Its early prime focus was upon the first offenders where a program of employment, educational opportunities, physical education in addition to the scheme of restricted association was credited for a relatively low level of re-offending.[4]

In 2015 Goulburn attracted controversy after a prisoner who was housed in the maximum security wing escaped after he cut through a gate at the back of a small secure exercise yard attached to his cell, tied bed sheets together to scale a wall, and put a pillow around his waist to avoid being hurt by razor wire.[9][10] In the same year the Minister for Corrections announced that security would be tightened following a breach when an inmate was caught with a contraband mobile phone that he used to upload pictures and text to a social media website.[11][12]

In late 2016 a 2-year trial of mobile phone jamming equipment at the prison was approved by the Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA);[13] following a successful trial of jamming at the Lithgow Correctional Centre.[14]

High-Risk Management Correctional Centre

Opened in 2001 at a cost of A$20 million,[15] the Super Maximum facility is located within the confines of the Goulburn Correctional Centre. Initially called the High-Risk Management Unit (HRMU, also referred to by inmates as HARM-U), it was Australia's first Supermax prison since the closure of the Katingal facility at the Long Bay Correctional Centre in 1978. The facility is the most secure prison within the NSW correctional system, and the inmates are subject to very strict daily regimes, and under intense scrutiny by security. Goulburn HRMCC has received complaints by prisoners, including the lack of natural light and fresh air; access to legal books; the use of isolation and solitary confinement; limited and enclosed exercise; self-mutilation and harsh treatment.[16][17] A 2008 report by the New South Wales Ombudsman explained that there is "no doubt… that the HRMU does not provide a therapeutic environment for these inmates".[18]

In spite of the security measures inside the HRMCC, in June 2011 it was reported that an unnamed inmate in the Centre had allegedly smuggled a mobile phone into the unit and plotted two kidnappings and a shooting. Criminal charges were laid against the inmate and his alleged co-conspirators.[19]

Heritage listing

The Goulburn Correctional Centre is significant for the strength of its original radial plan centred on the chapel, and the strength of the spatial relationships created by the plan. It has a close relationship with Goulburn township. Both town and institution have grown together and are economically and socially interdependent. It has a recorded association with a number of famous and infamous characters. It is also significant because of the way its continuous 110-year history of penal use is embodied in its physical fabric and documentary history.[20][6]

Goulburn Correctional Centre was listed on the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 2 April 1999 having satisfied the following criteria.[6]

The place is important in demonstrating the course, or pattern, of cultural or natural history in New South Wales.

The Goulburn Correctional Centre has a recorded association with a number of famous and infamous characters, both staff and inmates, including a Victoria Cross winner, bushrangers, larrikins, labour leaders and murderers.[20][6]

The place is important in demonstrating aesthetic characteristics and/or a high degree of creative or technical achievement in New South Wales.

The Goulburn Correctional Centre is significant for the strength of its original radial plan centred on the chapel, and the strength of the spatial relationships created by the plan. It is significant for the quality, inventiveness and durability of its original masonry, the unusually fine and sturdy roof structures in the chapel and radial wings and the harmonious textures and colours of its original brick, stone, render, slate and iron work. It has a pleasant location above the junction of the Wollondilly and Mulwarree Ponds with views to the north and east.[20][6]

The place has strong or special association with a particular community or cultural group in New South Wales for social, cultural or spiritual reasons.

The Goulburn Correctional Centre has a close relationship with Goulburn township. Both town and institution have grown together and are economically and socially interdependent. Goulburn has become the major judicial and penal centre of the Southern Highlands.[20][6]

The place has potential to yield information that will contribute to an understanding of the cultural or natural history of New South Wales.

The Goulburn Correctional Centre is significant because of the way its continuous 110-year history of penal use is embodied in its physical fabric and documentary history.[20][6]

The place possesses uncommon, rare or endangered aspects of the cultural or natural history of New South Wales.

Goulburn was one of the two Maclean-inspired gaols in NSW which best incorporated all that had been learned of penal design in the nineteenth century. The other, Bathurst Correctional Complex, has lost its chapel and been substantially remodelled.[20][6]

Notable prisoners

The following individuals have served all or part of their sentence at the Goulburn Correctional Centre:

| Inmate name | Date sentenced | Length of sentence | Currently incarcerated | Date eligible for release | Nature of conviction / Notoriety | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Malcolm George Baker | 6 August 1993 | Six consecutive terms of life imprisonment plus 25 years | Yes | No possibility of parole | Central Coast Massacre, 1992 | [21] |

| Darryl Burrell | 20 years | Died in 2012 of cancer | Convicted of armed robbery. Managed to escape briefly after playing soccer for the prison team. | [22] | ||

| Leslie Camilleri | Two consecutive terms of life imprisonment plus 183 years | Yes | No possibility of parole | The Bega schoolgirl murders and the murder of Prue Bird in 1992; held at the prison before being extradited. | ||

| Khaled Cheikho | 15 February 2010 | 27 years | Yes | Conspiring to manufacture explosives for use in the 2005 Sydney terrorism plot | [23][24] | |

| Moustafa Cheikho | 26 years | Yes | ||||

| Ray Denning | Armed robber and serial prison escapee. | [25] | ||||

| Mohamed Ali Elomar | 15 February 2010 | 28 years | Yes | Conspiring to manufacture explosives for use in the 2005 Sydney terrorism plot | [23][24][26] | |

| Sef Gonzales | Three consecutive terms of life imprisonment | Yes | No possibility of parole | The murders of his parents, Teddy and Mary Loiva, and younger sister Clodine. | ||

| Bassam Hamzy | The 1998 shooting murder of Kris Toumazis outside a Sydney nightclub, and was subsequently convicted for conspiring to murder a witness against him. Founder of the Brothers for Life street gang. | [27] | ||||

| Abdul Rakib Hasan | 15 February 2010 | 26 years | Yes | Conspiring to manufacture explosives for use in the 2005 Sydney terrorism plot | [23][24] | |

| Robert Hughes | 16 May 2014 | Ten years and nine months with a non-parole period of six years | Yes | April 2020 | Actor and star of Australian sitcom Hey Dad!, sentenced for two counts of sexual assault, seven counts of indecent assault, and one count of committing an indecent act involving girls from 6 to 15 during the 1980s. | [28][29] |

| Sam Ibrahim | A brother of John Ibrahim, pleaded guilty to possession of four prohibited weapons. | [30] | ||||

| Mohammed Omar Jamal | 15 February 2010 | 23 years | Yes | Conspiring to manufacture explosives for use in the 2005 Sydney terrorism plot | [23][24] | |

| Stephen Wayne "Shorty" Jamieson | 19 September 1990 | Life imprisonment plus 25 years | Yes | No possibility of parole | The murder of Janine Balding. | |

| Michael Kanaan | Three consecutive terms of life imprisonment plus 50 years 4 months | Yes | No possibility of parole | Three murders in Sydney in 1998. | ||

| Bilal Khazal | 25 September 2009 | 14 years | Yes | 9-year non-parole period | For producing a book whilst knowing it was connected with assisting a terrorist attack. | [31] |

| Ivan Milat | Seven consecutive terms of life imprisonment plus 18 years | Died from esophageal and stomach cancer on 27 October 2019, at Long Bay Correctional Centre, Malabar, New South Wales | Deceased | The Belanglo State Forest backpacker murders. | [32] | |

| Les Murphy | Life imprisonment with a non-parole period of 34 years | Yes | Unlikely to ever be released | The murder of Anita Cobby. | ||

| Michael Murphy | Life imprisonment plus 50 years | Died 21 February 2019 | No possibility of parole | [33] | ||

| Malcolm Naden | Life imprisonment plus 40 years | Yes | No possibility of parole | Two murders, an indecent assault on a 12-year-old girl, and the attempted murder of a police officer. At the time of his arrest in 2012, Naden was Australia's most wanted fugitive. | [34] | |

| Ngo Canh Phuong | Life imprisonment | Yes | No possibility of parole | The assassination of Cabramatta MP John Newman. | ||

| George Savvas | 25 years | Deceased in 1997 | n/a | A wholesale narcotics dealer who escaped from the prison for nine months in 1997. | [35] | |

| Bilal Skaf | 31 years' imprisonment | Yes | 28-year non-parole period | The Sydney gang rapes in 2000. | [36] | |

| John Travers | Life imprisonment plus 65 years | Yes | No possibility of parole | The murder of Anita Cobby. | ||

| Mark Valera (van Krevel) | Two consecutive terms of life imprisonment | Yes | No possibility of parole | The 1998 murders of David O'Hearn and Frank Arkell. |

References

Citations

- Mitchell, Alex (22 April 2007). "Mastermind recruiting Islamic gang inside super jail". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 6 January 2012.

- "Goulburn Correctional Centre complex". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Office of Environment and Heritage. Retrieved 15 September 2017.

- "Fast Fact: Goulburn Gaol". Tourism Business Unit of Goulburn Mulwaree Council. Retrieved 5 January 2012.

- "Goulburn Gaol (1847 - 1928) / Goulburn Reformatory (1928 - 1949) / Goulburn Training Centre (1949 - 1993) / Goulburn Correctional Centre (1993 - )". State Records. Government of New South Wales. 1996.

- State Projects 1995; Kerr 1994

- "Goulburn Correctional Centre complex". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Office of Environment and Heritage. H00808. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- State Projects 1995

- Kerr 1994: 20-21

- "Maximum security prisoner Stephen Jamieson ties bed sheets together, climbs jail wall to escape from Goulburn prison". ABC News. Australia. 18 August 2015. Retrieved 18 August 2015.

- "Australia inmate captured after using bed sheets to flee". BBC News. 18 August 2015. Retrieved 24 December 2015.

- Ralston, Nick (30 September 2015). "Prisoner Beau Wiles posts to Facebook, escapes from Goulburn jail". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 24 December 2015.

- "Prisoner escapes from Goulburn Correctional Centre NSW". ABC News. Australia. 30 September 2015. Retrieved 24 December 2015.

- Cole, David (1 November 2016). "Phone jammer at jail soon". Goulburn Post. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- "NSW jail trials phone-jamming technology". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 24 September 2013. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- "Chronology of the Prisoner Movement in Australia". Justice Action. Archived from the original on 20 January 2012. Retrieved 6 January 2012.

- Brown, David (5 September 2003). "Contemporary comment: The Nagle Royal Commission 25 years on (speech delivered to the NSW Council of Liberties at NSW Parliament House". Current Issues in Criminal Justice. 15 (2): 170–175.

- Brown, David (2004). "Royal Commissions and criminal justice: behind the ideal.". In Gilligan, G; Pratt, J (eds.). Crime, Truth and Justice: Official inquiry, discourse, knowledge. United Kingdom: William Publishing.

- Barbour, Bruce (2008). "Corrections: High-Risk Management Unit". Annual Report 2007 – 2008 (PDF). New South Wales Ombudsman. p. 128. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 March 2012. Retrieved 6 January 2012.

- "Goulburn SuperMax inmate using smuggled mobile phone allegedly plotted kidnappings and shooting". The Daily Telegraph. Australia. 9 June 2011. Retrieved 6 January 2012.

- Kerr 1994: 22

- Anderson, John (1998). "SENTENCING FOR "LIFE" IN NEW SOUTH WALES" (PDF). Australia and New Zealand Society of Criminology. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 September 2009. Retrieved 21 April 2009.

- Molloy, Paul; Dasey, Jason (23 June 1980). "Controls on prisoners to be tightened". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 24 December 2015.

- "Terrorist prisoners complain about conditions, halal food prices in NSW maximum security jail". Y7 News. 1 August 2016. Retrieved 16 September 2017.

- Rice, Deborah (12 December 2014). "Sydney men lose appeal against 2009 terrorism convictions". ABC News. Australia. Retrieved 16 September 2017.

- Jack The Insider Blog (24 August 2011). "Ray Denning and lessons un-learnt in our justice system". The Australian. Archived from the original on 15 January 2013. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- Law, James; O'Neill, Marnie (31 July 2014). "Mohamed "Moey" Elomar goes from celebrated boxing champion to wanted terrorist". news.com.au. Retrieved 16 September 2017.

- Sutton, Candace (13 August 2013). "Is Australia's most dangerous gangster Bassam Hamzy still in control?". news.com.au. Retrieved 24 December 2015.

- "Robert Hughes sentenced for child sex offences". SBS News. 16 May 2014.

- "Hey Dad! actor Robert Hughes taunted and pelted with excrement by fellow inmates". news.com.au. 3 August 2015. Retrieved 24 December 2015.

- Barrett, David (24 June 2009). "Sam Ibrahim's wife doesn't want him in Supermax". The Daily Telegraph. Australia. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- Rubinsztein-Dunlop, Sean; Dredge, Suzanne (10 October 2016). "Islamic State: Counter-terrorism officials fear Supermax prison further radicalising inmates". 7.30. Australia: ABC TV. Retrieved 16 September 2017.

- Robinson, Georgina (27 January 2009). "Ivan Milat cuts off a finger". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- Cockburn, Paige (22 February 2019). "Killer of Sydney nurse Anita Cobby dies in prison". ABC News. Retrieved 22 February 2019.

- Walsh, Gerard (23 March 2012). "Naden in 'good spirits' in Supermax". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 23 March 2012.

- Gibbs, Stephen (21 January 2006). "Great escapes". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- "Skaf lampoons gang rape". The Sunday Age. Melbourne. AAP. 20 July 2003. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

Sources

- Attribution

Further reading

- Cronin, Michelle (2001). "Goulburn jail a hell-hole, says activist." Canberra Times

- (2001). "Australia's 'most secure' prison to open at Goulburn today." Canberra Times. 1 June.

- (2007). "Gang Rapist Bashed in Prison." Canberra Times. 10 February.

- (1997). "George back in jail after two minutes in court." Daily Telegraph (Sydney). 22 March.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Goulburn Correctional Centre. |

- Goulburn Correctional Centre webpage – part of Corrective Services NSW

- Masters, Chris (17 November 2005). "SuperMax". Four Corners. Retrieved 4 January 2012. – investigative report with transcript and broadband links available.

- Watson, Rhett (9 May 2009). "Inside the walls of SuperMax prison, Goulburn". The Daily Telegraph. Australia. Retrieved 4 January 2012. – a journalist's view on spending time in Goulburn's SuperMax, at the invitation of the Commissioner of Corrective Services.