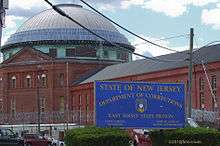

East Jersey State Prison

East Jersey State Prison (EJSP) is a maximum-security prison operated by the New Jersey Department of Corrections in Avenel, Woodbridge Township, New Jersey. It was established in 1896 as Rahway State Prison, and was the first reformatory in New Jersey, officially opening in 1901.[1] It houses approximately 1,500 men as of 2013.[2]

| |

| |

| Location | 1100 Woodbridge Road Avenel, New Jersey |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 40°35′28.7″N 74°16′02.7″W |

| Status | Open |

| Security class | Mixed |

| Capacity | 1227 |

| Opened | 1901 |

| Managed by | New Jersey Department of Corrections |

General information

- Although the prison's mailing address is in Rahway, the prison is located just outside of Rahway in Avenel.

- The prison's large dome is a landmark visible from nearby US Route 1–9 and New Jersey Transit's North Jersey Coast Line routes.

- The Education Department of East Jersey State Prison offers a variety of programs to the inmates. Vocational training courses include auto-body, auto mechanics, culinary arts, painting and decorating, and horticulture. The prison offers primary education (A.B.E. Course) and secondary education (GED) courses to the inmates. Inmates who are high school or GED graduates can take college classes offered through Union County College's "Project Inside" program.

- In about 2008, the yellow paint was removed from the brick of wings 1–4, re-creating the look and feel of the original 1896 building.

- Within the walls of the prison is an independent unit, the Special Treatment Unit, which houses sexually violent predators civilly committed. Less than 1/4 mile outside is the Adult Diagnostic and Treatment Center, New Jersey's facility for incarcerated sex offenders. Inmates of the three units have no contact with each other.

History

In 1895, the New Jersey Legislature voted to establish the state's first reformatory. A year later, construction began at Rahway on state property known as Edgar Farm.[3] "Rahway State Prison" opened in 1901 and originally housed first-time male offenders between the ages of 16 and 30.[3]

The first superintendent, J. E. Heg, served only for a year. He was succeeded by Joseph W. Martin, who led the institution until his death in 1909.[4] Martin was succeeded by Dr. Frank Moore, who retired in 1929.[5]

The prison features a large walled compound 21 acres (85,000 m2) in size, which contains the administration building, cell houses, schoolrooms, chapel, shops, and other buildings. The prison was surrounded by hundreds of acres of farmland that the inmates worked.[1][5] By 1908, there were two four-tiered cell houses. One cell house contained 256 cells measuring 9'x5'x8.6'H, while the other had 384 cells that were only 7.1'x5'x8'H. A 1928 inspection reported that the cells were equipped "with a fair quality of toilet and lavatory."[1]

New Jersey Reformatory

When the institution opened in 1901, it was called simply the New Jersey Reformatory and held 193 men.[3] The number of inmates had increased to 525 by 1912 and to 745 by 1928.[1][3] Of the 514 prisoners admitted during 1928, 304 (59%) were under twenty years of age, 164 (32%) were twenty to twenty-four, and 46 (9%) were from twenty-five to twenty-nine years old, with a racial breakdown of 406 (79%) White and 108 (21%) African-American.[1]

Rahway was originally run on a conduct "grading" system. A book of rules and regulations supplied to each inmate when he arrived discussed what was expected of him and the consequences of violating the rules. All inmates entered the prison in the "second grade" and had the opportunity to advance or be demoted depending on their behavior.[1] Inmates in different grades were granted different privileges.

The inmates' days at Rahway consisted primarily of school and work. They woke at 5:45 a.m. with lights out at 9 p.m. Those who had to attend school went to classes for half the day and worked the other half. The prison offered vocational training and jobs, including tailoring, cooking, shoe-making, printing, electrical work, farming/gardening, plumbing, and painting.[3]

Transition to adult prison

- In 1929, with the opening of nearby reformatories at Annandale (1928) and Bordentown (1937), Rahway State Prison changed from a reformatory to a prison for adult males.[4][5]

- In 1930, construction began on additions to the institution. Between 1931 and 1932, industrial and laundry buildings were added.

- A new dormitory, "Two Wing", was built in 1932. It contained two dormitories housing 150 men each, thereby increasing the prison's capacity to 900 inmates.[5]

- In 1951, Rahway's capacity was furthered increased to 1,000, when the last wing, "Three Wing", was constructed. As years passed, renovation on the institution continued.

- In 1967, one of the old buildings was improved and made into "Five Wing".

- From 1985 to 1988, trailers were erected and old buildings renovated (textile and laundry) for housing and dining facilities. These new additions became "Six, Seven, and Eight Wings".[4]

Riots and escapes

From April 17–22, 1952, prisoners took officers hostage during a riot after officers beat inmates with nightsticks. The riot ended when the inmates were gassed.[6] On Thanksgiving Day in 1971, 500 inmates held 6 hostages, including the warden, for 24 hours. Six officers were injured, three with stab wounds in the early hours of the riot.[6] The inmates demanded a more sufficient diet, regulation of commissary prices, improvement of the educational system and vocation training, better discipline of officers, and additional medicine supplies including aspirin. Ultimately, the prison was retaken with no loss of life and the captives were set free without the use of firearms.[3][7]

On August 11, 1972, three convicted murderers escaped by sawing through the bars of a third-floor window. Three officers were held responsible for the escape and suspended. In August 1980, in an effort to reduce the numbers of escapes, the prison issued gray prison uniforms to the prisoners.

Notable inmates

Rubin "Hurricane" Carter– (#45472) Carter spent over 18 years at Rahway (1967–1985). He was a well-known, former middleweight fighter before being convicted and sentenced to two life terms for murder. While there, Carter wrote an autobiography called The Sixteenth Round, which was published in 1975. The book became instrumental in having his convictions overturned, inspiring many to take up for Carter's cause. It made Carter's struggle something of a cause célèbre, motivating legendary boxer Muhammad Ali to lead a march of 1600 people to the New Jersey state capital on his behalf on October 17, 1975.[8] Carter's book also inspired a song by popular folk rock singer-songwriter, Bob Dylan in 1975. Dylan held a concert on Carter's behalf, called "Night of the Hurricane", playing for 20,000 people in December 1975, just 3 months before Carter's first conviction was overturned. A movie portraying Rubin's story and starring Denzel Washington was released in 1999. The best-selling biography Hurricane: The Miraculous Journey of Rubin Carter was written by James S. Hirsch in 2000.[9]

Prison name change

On November 30, 1988, at the request of the citizens of Rahway, NJ, Rahway State Prison was renamed East Jersey State Prison.[10] Residents claimed that being identified with the prison stigmatized the city and affected property values.[11] However, residents in the region surrounding still refer to building by its former name.

In popular culture

Boxing

High-profile professional boxers who were incarcerated in East Jersey State Prison:

- Former middleweight contender Rubin "Hurricane" Carter, who was released in 1985 after being sentenced to two consecutive life terms.[12]

- Dwight Muhammad Qawi, who became a two-time world champion after his release from East Jersey State Prison.

- James Scott, a title contender, who had many bouts inside the prison itself, including a fight against Dwight Muhammad Qawi in 1981.[13]

Music

- The Escorts, a R&B group, was discovered by record producer George Kerr during an inmate variety show that Kerr attended with Linda Jones. Kerr relentlessly and successfully petitioned the federal government to record an album with the group of inmates from behind bars in 1972. A mobile recording unit was brought to the prison where the group recorded their first hit album, All We Need Is Another Chance,[14] in just nine hours. The album would go on to reach #41 on Billboard's Hot Soul Singles[15] after its release in 1973. The group recorded a second album, 3 Down 4 to Go,[16] later in the same year. A documentary film, titled All We Need Is Another Chance[17] was released in 2017.

- The 1975 Bob Dylan song, "Hurricane" was inspired by inmate and former middleweight contender Rubin "Hurricane" Carter.[12]

- Lifers Group, a hip hop group, grew out of the Lifers Group Juvenile Awareness Program portrayed in Scared Straight!. In 1991, the group released an album and an EP, titled "#66064", featuring songs, "The Real Deal" and "Belly of the Beast".[18] A 30-minute documentary, directed by Penelope Spheeris, focusing on the group's songs and depicting life in East Jersey State, was released in 1992, and was nominated for a Grammy Award for Best Long Form Music Video[19][20]

- "Rahway Prison" is mentioned in the lyrics of the Traveling Wilburys 1988 song "Tweeter and the Monkey Man"

- "Rahway State" is mentioned in the lyrics of the East River Pipe song "Where Does All The Money Go?"

- Max B, the American rapper, was convicted in 2009 for multiple offenses, including conspiracy to murder. His 75-year sentence has since been reduced to 12 years and he is set to be released in 2021.

Television

- On May 8, 2000, an exposé of the history of EJSU first aired on an episode of History Channel's program, The Big House, hosted by Paul Sorvino. (Season 2, Episode 4)

- In 2003, the prison is mentioned in an episode of Arrested Development (season 1, episode 5,"Visiting Ours"). Character, George Bluth is concerned for his prison's softball team because they are "...playing Rahway next week..."[21]

- In 2008, Rahway State Prison is mentioned in the Flavor of Love 3 episode, "Neverwed Game" Guest star, Arsenio Hall comments on Flavor Flav's clothes, saying that Flav looks good in the color orange, as long as it does not say "Rahway" across the front.

- In 2010, Rahway Prison is mentioned in Season 1, Episode 9, of Boardwalk Empire. As James Darmondy is escorted to a cell, he passes a friend Billy. Billy is upset as he is being sent "up river, to Rahway".

Movies

East Jersey State Prison, with its distinctive architecture, including the large dome and radial cell blocks, along with its imposing metal gates and proximity to New York City, has made it a favorable filming location for many feature films..[22]

1970s

- Crazy Joe (1974) – Starring Peter Boyle. The story of the life of Joseph Gallo, a member of the Colombo crime family.[22]

- Scared Straight! (1978) - The prison became famous and synonymous with this 1978 Oscar-winning documentary, which was filmed entirely within the walls of the prison. It was a raw, unscripted exposé of prison life, where inmate with life sentences (called The Lifers' Group) fiercely warned delinquent teens of the brutal realities of prison. The film won the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature in 1978,[23] and two Emmy Awards for Outstanding Individual Achievement–Informational Program and Outstanding Informational Program in 1979.[24]

1980s

- Something Wild (1986) – Starring Jeff Daniels, Melanie Griffith and Ray Liotta

- Lock Up (1989) – Starring Sylvester Stallone and Donald Sutherland

1990s

- City of Hope (1991) – (Reference made to the prison)

- Malcolm X (1992) – Starring Denzel Washington

- Rounders (1998) – Starring Matt Damon and Edward Norton

- He Got Game (1998) – Starring Denzel Washington

- The Hurricane (1999) – The biographical drama of boxer, Rubin "Hurricane" Carter, starring Denzel Washington

2000s

- Ocean's Eleven (2001) – Starring Brad Pitt and George Clooney

2010s

- Jersey Boys (2014) – Directed and produced by Clint Eastwood based on the musical of the same name, telling the story of the musical group, The Four Seasons

- All We Need Is Another Chance (2017) – A documentary film on R&B music group, The Escorts, directed by Corbett Jones

- The Irishman (2019) - Directed by Martin Scorsese, starring Al Pacino, Robert De Niro & Joe Pesci, based on the life of Teamster, Frank Sheeran

References

- Cox, William, Lovell Bixby and William Root, "Handbook of American Prisons and Reformatories," Vol. 1, NY: The Osborne Assoc., 1933

- State of New Jersey Department of Corrections Contact Us. Accessed December 23, 2013.

- White, K., East Jersey State Prison Celebrates 100 Years, 1996, available from East Jersey State Prison

- East Jersey State Prison: Brief History, March 1995, available from East Jersey State Prison

- Garret, Paul and Austin MacCormick, "Handbook of American Prison and Reformatories," NY: National Society of Penal Information, Inc., 1929

- Reilly, M., "Locked In Time: East Jersey State Prison marks 100 years of changeing [sic?] penal roles. The Star Ledger. March 26, 1996.

- "Riot at the big house", Home News Tribune, August 17, 2004. Accessed August 6, 2007.

- JANSON, DONALD (October 18, 1975). "Ali Leads 1,600 at a Rally in Trenton For Release of Carter From Prison". The New York Times. Retrieved February 10, 2017 – via www.nytimes.com.

- "Rubin Carter Biography – Boxer (1937–2014)". www.Biography.com. February 16, 2016. Retrieved February 13, 2017.

- What's in a name? Plenty if we're talking prison, Home News Tribune, February 15, 2001.

- Reilly, M., 100 years inside (and outside) the walls. The Star Ledger. March 26, 1996

- Raab, Selwyn. "UNUSUAL LEGAL MOVE FREED RUBIN CARTER, LAWYERS SAY", The New York Times, November 10, 1985. Accessed November 11, 2007. "Mr. Carter had received two consecutive life terms, or a minimum of 30 years. Judge Sarokin ordered him released from Rahway State Prison without bail on Friday."

- "Dwight Muhammad Qawi". International Boxing Hall of Fame. 2004. Retrieved July 31, 2016.

- All We Need Is Another Chance (Remastered) by The Escorts on Apple Music, 1973, retrieved 2018-01-04

- Inc, Nielsen Business Media (1973-07-07). Billboard. Nielsen Business Media, Inc.

- 3 Down 4 to Go (Remastered) by The Escorts on Apple Music, 1973, retrieved 2018-01-04

- "ALL WE NEED IS ANOTHER CHANCE | Documentary Feature". All We Need Is Another Chance. Retrieved 2018-01-04.

- LUSTIG, JAY (January 5, 2015). "'Belly of the Beast,' Lifers Group". Institute for Nonprofit News. Retrieved November 4, 2016.

- Lynch, Colum (February 25, 1992). "Inmates Take Rap—to the Grammys : Pop music: Lifers Group can't attend ceremonies, but the band is nominated for its stark long-form video". www.articles.latimes.com. Retrieved November 4, 2016.

- "Grammy Awards – Awards for 1992". www.imdb.com. February 25, 1992. Retrieved November 4, 2016.

- Stroud, Brandon (February 28, 2013). "Sports On TV: Arrested Development's 15 Greatest Sports Moments". www.uproxx.com. Retrieved March 23, 2017.

- Bruder, Jessica (2003-10-05). "LAW AND ORDER; State Has Film Industry All Locked Up". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-08-30.

- "THE 51ST ACADEMY AWARDS | 1979". www.oscars.org. April 9, 1979. Retrieved November 4, 2016.

- "Television Academy – Emmys". www.emmys.com. 1979. Retrieved November 4, 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to East Jersey State Prison. |

- East Jersey State Prison

- East Jersey State Prison old official website

- The Big House (S2,E4) May 8, 2000

- ESPN Classic Sports Century – Rubin "Hurricane" Carter