Seljuq dynasty

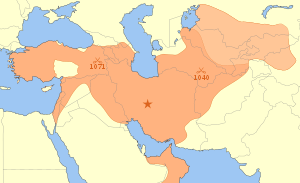

The Seljuq dynasty, or Seljuqs[1][2] (/ˈsɛldʒʊk/ SEL-juuk; Persian: آل سلجوق Al-e Saljuq),[3] was an Oghuz Turkic Sunni Muslim dynasty that gradually became Persianate and contributed to the Turco-Persian tradition[4][5] in the medieval Middle East and Central Asia. The Seljuqs established both the Seljuk Empire and the Sultanate of Rum, which at their heights stretched from Iran to Anatolia, and were targets of the First Crusade.

| Seljuq dynasty | |

|---|---|

| Country | Seljuk Empire Sultanate of Rum |

| Founded | 10th century – Seljuq |

| Titles | |

| Dissolution | Damascus: 1104 – Baqtash was dethroned by Toghtekin Great Seljuq: 1307 – Mesud II died |

Early history

The Seljuqs originated from the Qynyk branch of the Oghuz Turks,[6][7][8][9][10] who in the 9th century lived on the periphery of the Muslim world, north of the Caspian Sea and Aral Sea in their Yabghu Khaganate of the Oghuz confederacy,[11] in the Kazakh Steppe of Turkestan.[12] During the 10th century, due to various events, the Oghuz had come into close contact with Muslim cities.[13]

When Seljuq, the leader of the Seljuq clan, had a falling out with Yabghu, the supreme chieftain of the Oghuz, he split his clan off from the bulk of the Tokuz-Oghuz and set up camp on the west bank of the lower Syr Darya. Around 985, Seljuq converted to Islam.[13] In the 11th century the Seljuqs migrated from their ancestral homelands into mainland Persia, in the province of Khurasan, where they encountered the Ghaznavid empire. In 1025, 40,000 families of Oghuz Turks migrated to the area of Caucasian Albania.[14] The Seljuqs defeated the Ghaznavids at the Battle of Nasa plains in 1035. Tughril, Chaghri, and Yabghu received the insignias of governor, grants of land, and were given the title of dehqan.[15] At the Battle of Dandanaqan they defeated a Ghaznavid army, and after a successful siege of Isfahan by Tughril in 1050/51,[16] they established an empire later called the Great Seljuk Empire. The Seljuqs mixed with the local population and adopted the Persian culture and Persian language in the following decades.[17][18][19][20][21]

Later period

After arriving in Persia, the Seljuqs adopted the Persian culture and used the Persian language as the official language of the government,[17][18][22][23][24][25][26][27][28] and played an important role in the development of the Turko-Persian tradition which features "Persian culture patronized by Turkic rulers."[29] Today, they are remembered as great patrons of Persian culture, art, literature, and language.[17][18][19] They are regarded as the partial ancestors of the Western Turks – the present-day inhabitants of the Republic of Azerbaijan (historically known as Shirvan and Arran), Azerbaijan (historic Azerbaijan, also known as Iranian Azerbaijan), Turkmenistan, and Turkey.

Seljuq leaders

Rulers of the Seljuq Dynasty

The "Great Seljuqs" were heads of the family; in theory their authority extended over all the other Seljuq lines, although in practice this often was not the case. Turkish custom called for the senior member of the family to be the Great Seljuq, although usually the position was associated with the ruler of western Persia.

| Titular name(s) | Personal name | Reign | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bey بیگ |

Tughril طغرل |

1037–1063 | |

| Bey بیگ |

Suleiman[30] سُلَیمانشاہ |

1063[31] | |

| Sultan سلطان |

Alp Arslan الپ ارسلان |

1063–1072 | |

| Sultan سلطان Jalāl al-Dawlah جلال الدولہ |

Malik Shah I ملک شاہ اول |

1072–1092 | |

| Sultan سلطان Nasir al-Duniya wa al-Din ناصر الدنیا والدین |

Mahmud bin Malik Shah محمود بن ملک شاہ |

1092–1094 | |

| Sultan سلطان Abul Muzaffar Rukn al-Duniya wa al-Din أبو المظفر رکن الدنیا والدین |

Barkiyaruq bin Malik Shah برکیاروق بن ملک شاه |

1094–1105 | |

| Sultan سلطان Muizz al-Din معز الدین |

Malik Shah II ملک شاہ الثانی |

1105 | |

| Sultan سلطان Ghiyath al-Duniya wa al-Din غیاث الدنیا والدین |

Muhammad Tapar محمد تپار |

1105–1118 | |

| Sultan سلطان Muizz al-Din معز الدین |

*Ahmad Sanjar احمد سنجر |

1118–1153 | |

| Khwarazmian dynasty replaces the Seljuq dynasty. From 1157, the Oghuz took control of much of Khurasan, with the remainder in the hands of former Seljuq emirs. | |||

- Muhammad's son Mahmud II succeeded him in western Persia, but Ahmad Sanjar, who was the governor of Khurasan at the time being the senior member of the family, became the Great Seljuq Sultan.

Seljuq sultans of Hamadan

The rulers of western Persia, who maintained a very loose grip on the Abbasids of Baghdad. Several Turkic emirs gained a strong level of influence in the region, such as the Eldiduzids.

- Mahmud II 1118–1131

- 1131–1134 disputed between:

- Dawud

- Mas'ud (in Jibal and Iranian Azerbaijan) 1131

- Toghrul II 1132–1134

- Mas'ud 1133–1152

- Malik Shah III 1152–1153

- Muhammad II

- Suleiman Shah 1160–1161

- Arslan Shah 1161–1174

- Toghrul III 1174–1194

In 1194, Tugrul III was killed in battle with the Khwarezm Shah, who annexed Hamadan.

Seljuq rulers of Kerman

| History of the Turkic peoples pre-14th century |

|---|

History of the Turkic peoples |

| Tiele people |

| Göktürks |

|

| Khazar Khaganate 618–1048 |

| Xueyantuo 628–646 |

| Kangar union 659–750 |

| Turk Shahi 665-850 |

| Türgesh Khaganate 699–766 |

| Kimek confederation 743–1035 |

| Uyghur Khaganate 744–840 |

| Oghuz Yabgu State 750–1055 |

| Karluk Yabgu State 756–940 |

| Kara-Khanid Khanate 840–1212 |

| Ganzhou Uyghur Kingdom 848–1036 |

| Qocho 856–1335 |

| Pecheneg Khanates 860–1091 |

| Ghaznavid Empire 963–1186 |

| Seljuk Empire 1037–1194 |

| Cumania 1067–1239 |

| Khwarazmian Empire 1077–1231 |

| Kerait Khanate 11th century–13th century |

| Delhi Sultanate 1206–1526 |

| Qarlughid Kingdom 1224–1266 |

| Golden Horde 1240s–1502 |

| Mamluk Sultanate (Cairo) 1250–1517 |

Kerman was a province in southern Persia. Between 1053 and 1154, the territory also included Umman.

- Qawurd 1041–1073

- Kerman Shah 1073–1074

- Sultan Shah 1074–1075

- Hussain Omar 1075–1084

- Turan Shah I 1084–1096

- Iranshah ibn Turanshah 1096–1101

- Arslan Shah I 1101–1142

- Mehmed I (Muhammad) 1142–1156

- Tuğrul Shah 1156–1169

- Bahram-Shah 1169–1174

- Arslan Shah II 1174–1176

- Turan Shah II 1176–1183

- Muhammad Shah 1183–1187

Muhammad abandoned Kerman, which fell into the hands of the Oghuz chief Malik Dinar. Kerman was eventually annexed by the Khwarezmid Empire in 1196.

Seljuq rulers in Syria

- Abu Sa'id Taj ad-Dawla Tutush I 1085–1086

- Jalal ad-Dawlah Malik Shah I of Great Seljuq 1086–1087

- Qasim ad-Dawla Abu Said Aq Sunqur al-Hajib 1087–1094

- Abu Sa'id Taj ad-Dawla Tutush I (second time) 1094–1095

- Fakhr al-Mulk Radwan 1095–1113

- Tadj ad-Dawla Alp Arslan al-Akhras 1113–1114

- Sultan Shah 1114–1123

To the Artuqids

- Aziz ibn Abaaq al-Khwarazmi 1076–1079

- Abu Sa'id Taj ad-Dawla Tutush I 1079–1095

- Abu Nasr Shams al-Muluk Duqaq 1095–1104

- Tutush II 1104

- Muhi ad-Din Baktāsh (Ertaş) 1104

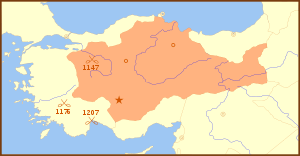

Seljuq sultans of Rum (Anatolia)

The Seljuq line, already having been deprived of any significant power, effectively ended in the early 14th century.

- Kutalmish 1060–1077

- Suleyman I (Suleiman) 1077–1086

- Dawud Kilij Arslan I 1092–1107

- Malik Shah 1107–1116

- Rukn ad-Din Mesud I 1116–1156

- Izz ad-Din Kilij Arslan II 1156–1192

- Ghiyath ad-Din Kaykhusraw I 1192–1196

- Suleyman II (Suleiman) 1196–1204

- Kilij Arslan III 1204–1205

- Ghiyath ad-Din Kaykhusraw I (second time) 1205–1211

- Izz ad-Din Kaykaus I 1211–1220

- Ala ad-Din Kayqubad I 1220–1237

- Ghiyath ad-Din Kaykhusraw II 1237–1246

- Izz ad-Din Kaykaus II 1246–1260

- Rukn ad-Din Kilij Arslan IV 1248–1265

- Ala ad-Din Kayqubad II 1249–1257

- Ghiyath ad-Din Kaykhusraw III 1265–1282

- Ghiyath ad-Din Mesud II 1282–1284

- Ala ad-Din Kayqubad III 1284

- Ghiyath ad-Din Mesud II (second time) 1284–1293

- Ala ad-Din Kayqubad III (second time) 1293–1294

- Ghiyath ad-Din Mesud II (third time) 1294–1301

- Ala ad-Din Kayqubad III (third time) 1301–1303

- Ghiyath ad-Din Mesud II (fourth time) 1303–1307

Gallery

Seljuq-era art: Ewer from Herat, Afghanistan, dated 1180–1210. Brass worked in repousse and inlaid with silver and bitumen. British Museum.

Seljuq-era art: Ewer from Herat, Afghanistan, dated 1180–1210. Brass worked in repousse and inlaid with silver and bitumen. British Museum. Head of Seljuq male royal figure, 12–13th century, from Iran. Carved and drilled stone with Iranian craftsmanship. Kept at the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Head of Seljuq male royal figure, 12–13th century, from Iran. Carved and drilled stone with Iranian craftsmanship. Kept at the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The Kharāghān twin towers, built in Iran in 1053 to house the remains of Seljuq princes

The Kharāghān twin towers, built in Iran in 1053 to house the remains of Seljuq princes

Family tree

See also

- Seljuk Empire

- Sultanate of Rûm

- Ottoman dynasty

- List of Sunni Muslim dynasties

References

- Neiberg, Michael S. (2002). Warfare in World History. Routledge. pp. 19–20. ISBN 9781134583423.

- Harris, Jonathan (2014). Byzantium and the Crusades. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 39–45. ISBN 9781780937366.

- Rāvandī, Muḥammad (1385). Rāḥat al-ṣudūr va āyat al-surūr dar tārīkh-i āl-i saljūq. Tihrān: Intishārāt-i Asāṭīr. ISBN 9643313662.

- Grousset, Rene, The Empire of the Steppes, (Rutgers University Press, 1991), 161,164; "renewed the Seljuk attempt to found a great Turko-Persian empire in eastern Iran..", "It is to be noted that the Seljuks, those Turkomans who became sultans of Persia, did not Turkify Persia-no doubt because they did not wish to do so. On the contrary, it was they who voluntarily became Persians and who, in the manner of the great old Sassanid kings, strove to protect the Iranian populations from the plundering of Ghuzz bands and save Iranian culture from the Turkoman menace."

- Nishapuri, Zahir al-Din Nishapuri (2001), "The History of the Seljuq Turks from the Jami’ al-Tawarikh: An Ilkhanid Adaptation of the Saljuq-nama of Zahir al-Din Nishapuri," Partial tr. K.A. Luther, ed. C.E. Bosworth, Richmond, UK. K.A. Luther, p. 9: "[T]he Turks were illiterate and uncultivated when they arrived in Khurasan and had to depend on Iranian scribes, poets, jurists and theologians to man the institution of the Empire")

- Concise Britannica Online Seljuq Dynasty Archived 2007-01-14 at the Wayback Machine article

- Merriam-Webster Online – Definition of Seljuk

- The History of the Seljuq Turks: From the Jami Al-Tawarikh (LINK)

- Shaw, Stanford. History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey (LINK)

- Golden, Peter B. (1992). An Introduction to the History of the Turkic People. Otto Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden. p. 209

- Wink, Andre, Al Hind: the Making of the Indo-Islamic World Brill Academic Publishers, Jan 1, 1996, ISBN 90-04-09249-8 pg.9

- Islam: An Illustrated History, p. 51

- Michael Adas, Agricultural and Pastoral Societies in Ancient and Classical History, (Temple University Press, 2001), 99.

- "The Caucasus & Globalization." Journal of Social, Political and Economic Studies. Institute of Strategic Studies of the Caucasus. Volume 5, Issue 1-2. 2011, p.116. CA&CC Press. Sweden.

- Bosworth, C.E. The Ghaznavids: 994-1040, Edinburgh University Press, 1963, 242.

- Tony Jaques, Dictionary of Battles and Sieges: F-O, (Greenwood Publishing Group, 2007), 476.

- O.Özgündenli, "Persian Manuscripts in Ottoman and Modern Turkish Libraries", Encyclopaedia Iranica, Online Edition, (LINK)

- Encyclopædia Britannica, "Seljuq", Online Edition, (LINK): "... Because the Turkish Seljuqs had no Islamic tradition or strong literary heritage of their own, they adopted the cultural language of their Persian instructors in Islam. Literary Persian thus spread to the whole of Iran, and the Arabic language disappeared in that country except in works of religious scholarship ..."

- M. Ravandi, "The Seljuq court at Konya and the Persianisation of Anatolian Cities", in Mesogeios (Mediterranean Studies), vol. 25–6 (2005), pp. 157–69

- M.A. Amir-Moezzi, "Shahrbanu", Encyclopaedia Iranica, Online Edition, (LINK): "... here one might bear in mind that Turco-Persian dynasties such as the Ghaznavids, Seljuqs and Ilkhanids were rapidly to adopt the Persian language and have their origins traced back to the ancient kings of Persia rather than to Turkish heroes or Muslim saints ..."

- F. Daftary, "Sectarian and National Movements in Iran, Khorasan, and Trasoxania during Umayyad and Early Abbasid Times", in History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Vol 4, pt. 1; edited by M.S. Asimov and C.E. Bosworth; UNESCO Publishing, Institute of Ismaili Studies: "... Not only did the inhabitants of Khurasan not succumb to the language of the nomadic invaders, but they imposed their own tongue on them. The region could even assimilate the Turkic Ghaznavids and Seljuks (eleventh and twelfth centuries), the Timurids (fourteenth–fifteenth centuries), and the Qajars (nineteenth–twentieth centuries) ..."

- Bosworth, C.E.; Hillenbrand, R.; Rogers, J.M.; Blois, F.C. de; Bosworth, C.E.; Darley-Doran, R.E., "Saldjukids," Encyclopaedia of Islam. Edited by: P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel and W.P. Heinrichs. Brill, 2009. Brill Online: "Culturally, the consistting of the Seljuq Empire marked a further step in the dethronement of Arabic from being the sole lingua franca of educated and polite society in the Middle East. Coming as they did through a Transoxania which was still substantially Iranian and into Persia proper, the Seljuqs with no high-level Turkish cultural or literary heritage of their own – took over that of Persia, so that the Persian language became the administration and culture in their land of Persia and Anatolia. The Persian culture of the Rum Seljuqs was particularly splendid, and it was only gradually that Turkish emerged there as a parallel language in the field of government and adab; the Persian imprint in Ottoman civilization was to remain strong until the 19th century.

- John Perry, THE HISTORICAL ROLE OF TURKISH IN RELATION TO PERSIAN OF IRAN in Iran & the Caucasus, Vol. 5, (2001), pp. 193–200. excerpt: "First, since the Turkish-speaking rulers of most Iranian polities from the Ghaznavids and Seljuks onward were already iranized and patronized Persian literature in their domains, the expansion of Turk-ruled empires served to expand the territorial domain of written Persian into the conquered areas, notably Anatolia and Central and South Asia."

- Ram Rahul. "March of Central Asia", Indus Publishing, pg 124: "The Seljuk conquest of Persia marked the triumph of the Sunni over Shii but without a decline in Persian culture. The Seljuks eventually adopted the Persian culture.

- Ehsan Yarshater, "Iran" in Encyclopedia Iranica: "The ascent of the Saljuqids also put an end to a period which Minorsky has called "the Persian intermezzo" (see Minorsky, 1932, p. 21), when Iranian dynasties, consisting mainly of the Saffarids, the Samanids, the Ziyarids, the Buyids, the Kakuyids, and the Bavandids of Tabarestan and Gilan, ruled most of Iran. By all accounts, weary of the miseries and devastations of never-ending conflicts and wars, Persians seemed to have sighed with relief and to have welcomed the stability of the Saljuqid rule, all the more so since the Saljuqids mitigated the effect of their foreignness, quickly adopting the Persian culture and court customs and procedures and leaving the civil administration in the hand of Persian personnel, headed by such capable and learned viziers as ‘Amid-al-Molk Kondori and Nezam-al-Molk."

- C.E. Bosworth, "Turkish expansion towards the west", in UNESCO History of Humanity, Volume IV: From the Seventh to the Sixteenth Century, UNESCO Publishing / Routledge, 2000. p. 391: "While the Arabic language retained its primacy in such spheres as law, theology and science, the culture of the Seljuk court and secular literature within the sultanate became largely Persianized; this is seen in the early adoption of Persian epic names by the Seljuk rulers (Qubād, Kay Khusraw and so on) and in the use of Persian as a literary language (Turkish must have been essentially a vehicle for everyday speech at this time). The process of Persianization accelerated in the thirteenth century with the presence in Konya of two of the most distinguished refugees fleeing before the Mongols, Bahā' al-Dīn Walad and his son Mawlānā Jalāl al-Dīn Rūmī, whose Mathnawī, composed in Konya, constitutes one of the crowning glories of classical Persian literature."

- Stephen P. Blake, Shahjahanabad: The Sovereign City in Mughal India, 1639–1739. Cambridge University Press, 1991. pg 123: "For the Seljuks and Il-Khanids in Iran, it was the rulers rather than the conquered who were 'Persianized and Islamicized'".

- Mehmed Fuad Koprulu, Early Mystics in Turkish Literature, Translated by Gary Leiser and Robert Dankoff, Routledge, 2006, pg 149: "If we wish to sketch, in broad outline, the civilization created by the Seljuks of Anatolia, we must recognize that the local, i.e. non-Muslim, element was fairly insignificant compared to the Turkish and Arab-Persian elements, and that the Persian element was paramount/The Seljuk rulers, to be sure, who were in contact with not only Muslim Persian civilization, but also with the Arab civilizations in al-jazīra and Syria – indeed, with all Muslim peoples as far as India – also had connections with {various} Byzantine courts. Some of these rulers, like the great 'Ala' al-Dīn Kai-Qubād I himself, who married Byzantine princesses and thus strengthened relations with their neighbors to the west, lived for many years in Byzantium and became very familiar with the customs and ceremonial at the Byzantine court. Still, this close contact with the ancient Greco-Roman and Christian traditions only resulted in their adoption of a policy of tolerance toward art, aesthetic life, painting, music, independent thought – in short, toward those things that were frowned upon by the narrow and piously ascetic views {of their subjects}. The contact of the common people with the Greeks and Armenians had basically the same result. {Before coming to Anatolia}, the Turks had been in contact with many nations and had long shown their ability to synthesize the artistic elements that they had adopted from these nations. When they settled in Anatolia, they encountered peoples with whom they had not yet been in contact and immediately established relations with them as well. 'Ala' al-Dīn Kai-Qubād I established ties with the Genoese and, especially, the Venetians at the ports of Sinop and Antalya, which belonged to him, and granted them commercial and legal concessions. Meanwhile, the Mongol invasion, which caused a great number of scholars and artisans to flee from Turkistan, Iran, Afghanistan, and Khwārazm and settle within the Empire of the Seljuks of Anatolia, resulted in a reinforcing of Persian influence on the Anatolian Turks. Indeed, despite all claims to the contrary, there is no question that Persian influence was paramount among the Seljuks of Anatolia. This is clearly revealed by the fact that the sultans who ascended the throne after Ghiyāth al-Dīn Kai-Khusraw I assumed titles taken from ancient Persian mythology, like Kai-Khusraw, Kai-Kā'ūs, and Kai-Qubād; and that 'Ala' al-Dīn Kai-Qubād I had some passages from the Shāhnāme inscribed on the walls of Konya and Sivas. When we take into consideration domestic life in the Konya courts and the sincerity of the favor and attachment of the rulers to Persian poets and Persian literature, then this fact {i.e. the importance of Persian influence} is undeniable. With regard to the private lives of the rulers, their amusements, and palace ceremonial, the most definite influence was also that of Iran, mixed with the early Turkish traditions, and not that of Byzantium."

- Daniel Pipes: "The Event of Our Era: Former Soviet Muslim Republics Change the Middle East" in Michael Mandelbaum, "Central Asia and the World: Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkemenistan and the World", Council on Foreign Relations, pg 79. Exact statement: "In Short, the Turko-Persian tradition featured Persian culture patronized by Turcophone rulers."

- Sevim, Ali (1993). ÇAĞRI BEY (PDF). 8. İstanbul: TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi. pp. 183–186. ISBN 978-9-7538-9435-7.

- Sümer, Faruk (2009). SELÇUKLULAR (PDF). 36. İstanbul: TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi. pp. 365–371. ISBN 978-9-7538-9566-8.

- Black, Jeremy (2005). The Atlas of World History. American Edition, New York: Covent Garden Books. pp. 65, 228. ISBN 9780756618612. This map varies from other maps which are slightly different in scope, especially along the Mediterranean and the Black Sea.

- Özaydın, Abdülkerim (2002). KAVURD BEY (PDF). 25. İstanbul: TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi. pp. 73–74. ISBN 978-9-7538-9403-6.

- Zahîrüddîn-i Nîsâbûrî, Selcûḳnâme, (Muhammed Ramazânî Publications), Tahran 1332, p. 10.

- Reşîdüddin Fazlullāh-ı Hemedânî, Câmiʿu’t-tevârîḫ, (Ahmed Ateş Publications), Ankara 1960, vol. II/5, p. 5.

- Râvendî, Muhammed b. Ali, Râhatü’s-sudûr, (Ateş Publications), vol. I, p. 85.

- Müstevfî, Târîḫ-i Güzîde, (Nevâî Publications), p. 426.

- Osman Gazi Özgüdenli (2016). MÛSÂ YABGU. EK-2. İstanbul: TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi. pp. 324–325.

- Sevim, Ali (1991). ATSIZ b. UVAK (PDF). 4. İstanbul: TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi. p. 92-93. ISBN 978-9-7538-9431-9.

- Sümer, Faruk (2002). KUTALMIŞ (PDF). 26. İstanbul: TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi. pp. 480–481. ISBN 978-9-7538-9406-7.

- Beyhakī, Târîḫ, (Behmenyâr), p. 71.

- Alptekin, Coşkun (1989). AKSUNGUR (PDF). 2. İstanbul: TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi. p. 196. ISBN 978-9-7538-9429-6.

- Sümer, Faruk (2009). Kirman Selçuks (PDF). 36. İstanbul: TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi. p. 377-379. ISBN 978-9-7538-9566-8.

- Özaydın, Abdülkerim (2012). TUTUŞ (PDF). 41. İstanbul: TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi. pp. 446–449. ISBN 978-9-7538-9713-6.

- Sümer, Faruk (2009). SELÇUKS of Syria (PDF). 36. İstanbul: TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi. pp. 385–386. ISBN 978-9-7538-9566-8.

- Bezer, Gülay Öğün (2011). TERKEN HATUN, the mother of MAHMÛD I (PDF). 40. İstanbul: TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi. p. 510. ISBN 978-9-7538-9652-8. Terken Khatun (wife of Malik-Shah I).

- Özaydın, Abdülkerim (2004). MELİKŞAH (PDF). 29. İstanbul: TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi. pp. 54–57. ISBN 978-9-7538-9415-9.

- Sümer, Faruk (1991). ARSLAN ARGUN (PDF). 3. İstanbul: TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi. p. 399-400. ISBN 978-9-7538-9430-2.

- Özaydın, Abdülkerim (1992). BERKYARUK (PDF). 5. İstanbul: TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi. p. 514-516. ISBN 978-9-7538-9432-6.

- Özaydın, Abdülkerim (2005). MUHAMMED TAPAR (PDF). 30. İstanbul: TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi. pp. 579–581. ISBN 978-9-7538-9425-8.

- Özaydın, Abdülkerim (2009). AHMED SENCER (PDF). 36. İstanbul: TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi. pp. 507–511. ISBN 978-9-7538-9566-8.

- Sümer, Faruk (2009). Irak Selçuks (PDF). 36. İstanbul: TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi. p. 387. ISBN 978-9-7538-9566-8.

- Özaydın, Abdülkerim (2003). MAHMÛD b. MUHAMMED TAPAR of Irak Selçuks (PDF). 27. İstanbul: TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi. p. 371-372. ISBN 978-9-7538-9408-1.

- Sümer, Faruk (2012). TUĞRUL I of Irak Selçuks (PDF). 41. İstanbul: TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi. p. 341-342. ISBN 978-9-7538-9713-6.

- Sümer, Faruk (2004). MES‘ÛD b. MUHAMMED TAPAR of Irak Selçuks (PDF). 29. İstanbul: TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi. p. 349-351. ISBN 978-9-7538-9415-9.

- Sümer, Faruk (1991). ARSLANŞAH b. TUĞRUL of Irak Selçuks (PDF). 3. İstanbul: TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi. p. 404-406. ISBN 978-9-7538-9430-2.

- Sümer, Faruk (2012). Ebû Tâlib TUĞRUL b. ARSLANŞAH b. TUĞRUL of Irak Selçuks (PDF). 41. İstanbul: TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi. p. 342-344. ISBN 978-9-7538-9713-6.

Further reading

- Grousset, Rene (1988). The Empire of the Steppes: a History of Central Asia. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. p. 147. ISBN 0813506271.

- Peacock, A.C.S., Early Seljuq History: A New Interpretation; New York, NY; Routledge; 2010

- Previté-Orton, C. W. (1971). The Shorter Cambridge Medieval History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.