Persianate society

A Persianate society is a society that is based on or strongly influenced by the Persian language, culture, literature, art and/or identity.[1]:6

.jpg)

The term "Persianate" is a neologism credited to Marshall Hodgson.[2] In his 1974 book, The Venture of Islam: The expansion of Islam in the Middle Periods, he defined it thus: "The rise of Persian had more than purely literary consequences: it served to carry a new overall cultural orientation within Islamdom.... Most of the more local languages of high culture that later emerged among Muslims... depended upon Persian wholly or in part for their prime literary inspiration. We may call all these cultural traditions, carried in Persian or reflecting Persian inspiration, 'Persianate' by extension."[3]:293–94[notes 1]

The term designates ethnic Persians but also societies that may not have been ethnically Persian or Iranian but whose linguistic, material or artistic cultural activities were influenced by or based on Persianate culture. Examples of pre-19th-century Persianate societies were the Seljuq,[4][5][6] Timurid,[7][8] Mughal,[9][10] and Ottoman dynasties,[11][12][13][14] as well as the Qarmatians who entertained Persianate notions of cyclical time even though they did not invoke the Iranian genealogies in which these precepts had converged. "Persianate" is a multiracial cultural category, but it appears at times to be a religious category of a racial origin.[15]:54

List of historical Persianate (or Persian-speaking) states/dynasties

Based in Greater Iran

- Ghaznavids

- Ghurid Empire

- Samanid Empire

- Great Seljuq Empire

- Khwarazmian dynasty

- Ilkhanate

- Timurid Empire

- Buyid dynasty

- Aq Qoyunlu

- Shirvanshah

- Safavid Empire

- Afsharid dynasty

- Zand dynasty

- Qajar dynasty

Based in Asia Minor

Based in South Asia

- Delhi Sultanate

- Mamluk Sultanate (Delhi)

- Khalji dynasty

- Tughlaq dynasty

- Sayyid dynasty

- Lodi dynasty

- Bengal Sultanate

- Qutb Shahi dynasty (Golconda Sultanate)

- Mughal Empire

- Sur Empire

- Hyderabad

History

Persianate culture flourished for nearly fourteen centuries. It was a mixture of Persian and Islamic cultures that eventually underwent Persification and became the dominant culture of the ruling and elite classes of Greater Iran, Asia Minor, and South Asia.[16]

When the peoples of Greater Iran were conquered by Islamic forces in the 7th and 8th centuries, they became part of an empire much larger than any previous one under Persian rule.[16] While the Islamic conquest led to the Arabization of language and culture in the former Byzantine territories, this did not happen in Persia. Rather, the new Islamic culture evolving there was largely based on pre-Islamic Persian traditions of the area,[17] as well as on the Islamic customs that were introduced to the region by the Arab conquerers.[18]

Persianate culture, especially among the elite classes, spread across the Muslim territories in western, central, and south Asia, although populations across this vast region had conflicting allegiances (sectarian, local, tribal, and ethnic) and spoke many different languages. It was spread by poets, artists, architects, artisans, jurists, and scholars, who maintained relations among their peers in the far-flung cities of the Persianate world, from Anatolia to India.[3]

Persianate culture involved modes of consciousness, ethos, and religious practices that have persisted in the Iranian world against hegemonic Arab Muslim (Sunni) cultural constructs.[15]:23–32 This formed a calcified Persianate structure of thought and experience of the sacred, entrenched for generations, which later informed history, historical memory, and identity among Alid loyalists and heterodox groups labeled by sharia-minded authorities as ghulāt. In a way, along with investing the notion of heteroglossia, Persianate culture embodies the Iranian past and ways in which this past blended with the Islamic present or became transmuted. The historical change was largely on the basis of a binary model: a struggle between the religious landscapes of late Iranian antiquity and a monotheist paradigm provided by the new religion, Islam.[15]:38

This duality is symbolically expressed in the Shiite tradition that Husayn ibn Ali, the third Shi'ite Imam, had married Shahrbanu,[19] daughter of Yazdegerd III, the last Sassanid king of Iran. This genealogy makes the later imams, descended from Husayn and Shahrbanu, the inheritors of both the Islamic Prophet Muhammad and of the pre-Islamic Sassanid kings.

Origins

After the Arab Muslim conquest of Iran, Pahlavi, the language of Pre-Islamic Iran, continued to be widely used well into the second Islamic century (8th century) as a medium of administration in the eastern lands of the Caliphate.[16] Despite the Islamization of public affairs, the Iranians retained much of their pre-Islamic outlook and way of life, adjusted to fit the demands of Islam. Towards the end of the 7th century, the population began resenting the cost of sustaining the Arab caliphs, the Umayyads, and in the 8th century, a general Iranian uprising—led by Abu Muslim Khorrasani—brought another Arab family, the Abbasids, to the Caliph's throne.

Under the Abbasids, the capital shifted from Syria to Iraq, which had once been part of the Sassanid Empire and was still considered to be part of the Iranian cultural domain. Persian culture, and the customs of the Persian Barmakid viziers, became the style of the ruling elite. Politically, the Abbasids soon started losing their control over Iranians. The governors of Khurasan, the Tahirids, though appointed by the caliph, were effectively independent. When the Persian Saffarids from Sistan freed the eastern lands, the Buyyids, the Ziyarids and the Samanids in Western Iran, Mazandaran and the north-east respectively, declared their independence.[16]

The separation of the eastern territories from Baghdad was expressed in a distinctive Persianate culture that became dominant in west, central, and south Asia, and was the source of innovations elsewhere in the Islamic world. The Persianate culture was marked by the use of the New Persian language as a medium of administration and intellectual discourse, by the rise of Persianised-Turks to military control, by the new political importance of non-Arab ulama and by the development of an ethnically composite Islamic society.

Pahlavi was the lingua franca of the Sassanian Empire before the Arab invasion, but towards the end of the 7th and the beginning of the 8th century Arabic became a medium of literary expression. In the 9th century, a New Persian language emerged as the idiom of administration and literature. The Tahirid and Saffarid dynasties continued using Persian as an informal language, although for them Arabic was the "language for recording anything worthwhile, from poetry to science",[20] but the Samanids made Persian a language of learning and formal discourse. The language that appeared in the 9th and 10th centuries was a new form of Persian, derivative of the Middle-Persian of pre-Islamic times, but enriched amply by Arabic vocabulary and written in the Arabic script.

The Persian language, according[21] to Marshall Hodgson in his The Venture of Islam, was to form the chief model for the rise of still other languages to the literary level. Like Turkish, most of the more local languages of high culture that later emerged among Muslims depended upon Persian (Urdu being a prime example). One may call these traditions, carried in Persian or reflecting Persian inspiration, ‘Persianate’ by extension. This seems[22] to be the origin of the term Persianate.

Spread

The Iranian dynasty of the Samanids began recording its court affairs in Persian as well as Arabic, and the earliest great poetry in New Persian was written for the Samanid court. The Samanids encouraged translation of religious works from Arabic into Persian. In addition, the learned authorities of Islam, the ulama, began using the Persian lingua franca in public. The crowning literary achievement in the early New Persian language was the Shahnameh (Book of Kings), presented by its author Ferdowsi to the court of Mahmud of Ghazni (998–1030). This was a kind of Iranian nationalistic resurrection: Ferdowsi galvanized Persian nationalistic sentiment by invoking pre-Islamic Persian heroic imagery and enshrined in literary form the most treasured folk stories.[16]

Ferdowsi's Shahnameh enjoyed a special status in Iranian courtly culture as a historical narrative as well as a mythical one. The powerful effect that this text came to have on the poets of this period is partly due to the value that was attached to it as a legitimizing force, especially for new rulers in the Eastern Islamic world:

In the Persianate tradition the Shahnameh was viewed as more than literature. It was also a political treatise, as it addressed deeply rooted conceptions of honor, morality, and legitimacy. Illustrated versions of it were considered desirable as expressions of the aspirations and politics of ruling elites in the Iranian world.[23]

The Persianate culture that emerged under the Samanids in Greater Khorasan, in northeast Persia and the borderlands of Turkistan exposed the Turks to Persianate culture;[24] The incorporation of the Turks into the main body of the Middle Eastern Islamic civilization, which was followed by the Ghaznavids, thus began in Khorasan; "not only did the inhabitants of Khurasan not succumb to the language of the nomadic invaders, but they imposed their own tongue on them. The region could even assimilate the Turkic Ghaznavids and Seljuks (11th and 12th centuries), the Timurids (14th and 15th centuries), and the Qajars (19th and 20th centuries).[25]

The Ghaznavids, the rivals and future successors of the Samanids, ruled over the southeastern extremities of Samanid territories from the city of Ghazni. Persian scholars and artists flocked to their court, and the Ghaznavids became patrons of Persianate culture. The Ghaznavids took with them Persianate culture as they subjugated Western and Southern Asia . Apart from Ferdowsi, Rumi, Abu Ali Sina, Al-Biruni, Unsuri Balkhi, Farrukhi Sistani, Sanayi Ghaznawi and Abu Sahl Testari were among the great Iranian scientists and poets of the period under Ghaznavid patronage.

Persianate culture was carried by successive dynasties into Western and Southern Asia, particularly by the Persianized Seljuqs (1040–1118) and their successor states, who presided over Iran, Syria, and Anatolia until the 13th century, and by the Ghaznavids, who in the same period dominated Greater Khorasan and parts of India. These two dynasties together drew the centers of the Islamic world eastward. The institutions stabilized Islamic society into a form that would persist, at least in Western Asia, until the 20th century.[16]

The Ghaznavids moved their capital from Ghazni to Lahore in modern Pakistan, which they turned into another center of Islamic culture. Under their patronage, poets and scholars from Kashgar, Bukhara, Samarkand, Baghdad, Nishapur, Amol and Ghazni congregated in Lahore. Thus, the Persian language and Persianate culture was brought deep into India[26] and carried further in the 13th century. The Seljuqs won a decisive victory over the Ghaznavids and swept into Khorasan; they brought Persianate culture westward into western Persia, Iraq, Anatolia, and Syria. Iran proper along with Central Asia became the heartland of Persian language and culture.

As the Seljuqs came to dominate western Asia, their courts were Persianized as far west as the Mediterranean Sea. Under their rule, many pre-Islamic Iranian traditional arts like Sassanid architecture were resurrected, and great Iranian scholars were patronized. At the same time, the Islamic religious institutions became more organized and Sunni orthodoxy became more codified.

The Persian jurist and theologian Al-Ghazali was among the scholars at the Seljuq court who proposed a synthesis of Sufism and Sharia, which became the basis for a richer Islamic theology. Formulating the Sunni concept of division between temporal and religious authorities, he provided a theological basis for the existence of the Sultanate, a temporal office alongside the Caliphate, which at that time was merely a religious office. The main institutional means of establishing a consensus of the ulama on these dogmatic issues was the Nezamiyeh, better known as the madrasas, named after its founder Nizam al-Mulk, a Persian vizier of the Seljuqs. These schools became the means of uniting Sunni ulama, who legitimized the rule of the Sultans. The bureaucracies were staffed by graduates of the madrasas, so both the ulama and the bureaucracies were under the influence of esteemed professors at the madrasas.[16]:14[20]:224–30

Shahnameh's impact and affirmation of Persianate culture

As the result of the impacts of Persian literature as well as to further political ambitions, it became a custom for rulers in the Persianate lands to not only commission a copy of the Shahnameh, but also to have his own epic, allowing court poets to attempt to reach the level of Ferdowsi:

Thus, as with any piece of historical writing, the Shahnameh can be evaluated as a historical source on two levels: firstly, for its contribution to the store of basic factual knowledge of a period, and secondly, for the light it sheds, intentionally or otherwise, on contemporary thought and politics.

— [27]

Iranian and Persianate poets received the Shahnameh and modeled themselves after it. Murtazavi formulates three categories of such works too: poets who took up material not covered in the epic, poets who eulogized their patrons and their ancestors in masnavi form for monetary reward, and poets who wrote poems for rulers who saw themselves as heroes in the Shahnameh,[28] echoing the earlier Samanid trend of patronizing the Shahnameh for legitimizing texts.[29]

First, Persian poets attempted to continue the chronology to a later period, such as the Zafarnamah of the Ilkhanid historian Hamdollah Mostowfi (d. 1334 or 1335), which deals with Iranian history from the Arab conquest to the Mongols and is longer than Ferdowsi's work.[30] The literary value of these works must be considered on an individual basis as Rypka cautions: "all these numerous epics cannot be assessed very highly, to say nothing of those works that were substantially (or literally) copies of Ferdowsi. There are however exceptions, such as the Zafar-Nameh of Hamdu'llah Mustaufi a historically valuable continuation of the Shah-nama"[31] and the Shahanshahnamah (or Changiznamah) of Ahmad Tabrizi in 1337–38, which is a history of the Mongols written for Abu Sa'id.

Second, poets versified the history of a contemporary ruler for reward, such as the Ghazannameh written in 1361–62 by Nur al-Din ibn Shams al-Din. Third, heroes not treated in the Shahnameh and those having minor roles in it became the subjects of their own epics, such as the 11th-century Garshāspnāmeh by Asadi Tusi. This tradition, chiefly a Timurid one, resulted in the creation of Islamic epics of conquests as discussed by Marjan Molé.[32] Also see the classification employed by Z. Safa for epics: milli (national, those inspired by Ferdowsi's epic), tarikhi (historical, those written in imitation of Nizami's Iskandarnamah) and dini for religious works.[33] The other source of inspiration for Persianate culture was another Persian poet, Nizami, a most admired, illustrated and imitated writer of romantic masnavis.[34]

Along with Ferdowsi's and Nizami's works, Amir Khusraw Dehlavi's khamseh came to enjoy tremendous prestige, and multiple copies of it were produced at Persianized courts. Seyller has a useful catalog of all known copies of this text.[35]

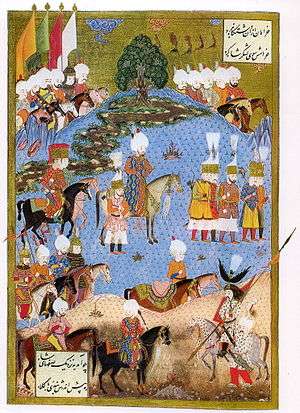

Mongol invasion

The culture of the Persianate world in the 13th, 14th, and 15th centuries inadvertently benefited by the invading hordes of Asia. The Mongols under Genghis Khan (1220–58) and Timur (Tamerlane, 1336–1405) stimulated the development of Persianate culture in Central and West Asia, because of the new concentrations of specialists of high culture created by the invasions. Many Iranians sought refuge in a few safe havens, particularly India, where scholars, poets, musicians, and fine artisans intermingled; because of the broad peace secured by the imperial systems established by the Ilkhanids and Timurids, scholars and artists, ideas and skills, and fine books and artifacts circulated freely over a wide area. The Ilkhanids and Timurids were patrons of Persianate high culture. Under their rule new styles of architecture based on pre-Islamic Iranian traditions were developed, Persian literature was encouraged and schools of miniature painting and book production were established at Herat, Tabriz and Esfahan.

In the 16th century, Persianate culture became sharply distinct from the Arab world to the west, the dividing zone falling along the Euphrates. Socially the Persianate world was marked by a system of ethnologically defined elite statuses: the rulers and their soldiery were non-Iranians in origin, but the administrative cadres and literati were Iranians. Cultural affairs were marked by a characteristic pattern of language use: New Persian was the language of state affairs, scholarship and literature and Arabic the language of religion.[26]

Safavids and the resurrection of Iranianhood in West Asia

The Safavid dynasty ascended to predominance in Iran in the 16th century—the first native Iranian dynasty since the Buyyids.[36][37][38] The Safavids, who were of mixed Kurdish, Turkic, Georgian, Circassian and Pontic Greek ancestry, moved to the Ardabil region in the 11th century. They re-asserted the Persian identity over many parts of West Asia and Central Asia, establishing an independent Persian state,[39] and patronizing Persian culture [16] They made Iran the spiritual bastion of Shi’ism against the onslaughts of orthodox Sunni Islam, and a repository of Persian cultural traditions and self-awareness of Persian identity.[40]:228

The founder of the dynasty, Shah Isma'il, adopted the title of Persian Emperor Pādišah-ī Īrān, with its implicit notion of an Iranian state stretching from Afghanistan as far as the Euphrates and the North Caucasus, and from the Oxus to the southern territories of the Persian Gulf.[40]:228 Shah Isma'il's successors went further and adopted the title of Shāhanshāh (king of kings). The Safavid kings considered themselves, like their predecessors the Sassanid Emperors, the khudāygān (the shadow of God on earth).[40]:226 They revived Sassanid architecture,[40]:226 build grand mosques and elegant charbagh gardens, collected books (one Safavid ruler had a library of 3,000 volumes), and patronized "Men of the Pen"[41]:105 The Safavids introduced Shiism into Persia to distinguish Persian society from the Ottomans, their Sunni archrivals to the west.[3]

Ottomans

At the beginning of the 14th century, the Ottomans rose to predominance in Asia Minor. The Ottomans patronized Persian literature for five and a half centuries and attracted great numbers of writers and artists, especially in the 16th century.[42] One of the most renowned Persian poets in the Ottoman court was Fethullah Arifi Çelebi, also a painter and historian, and the author of the Süleymanname (or Suleyman-nama), a biography of Süleyman the Magnificent.[43] At the end of the 17th century, they gave up Persian as the court and administrative language, using Turkish instead; a decision that shocked the highly Persianized Mughals in India.[41]:159 The Ottoman Sultan Suleyman wrote an entire divan in Persian language.[44] According to Hodgson:

The rise of Persian (the language) had more than purely literary consequence: it served to carry a new overall cultural orientation within Islamdom. Henceforth while Arabic held its own as the primary language of the religious disciplines and even, largely, of natural science and philosophy, Persian became, in an increasingly part of Islamdom, the language of polite culture; it even invaded the realm of scholarship with increasing effects. It was to form the chief model of the rise of still other languages. Gradually a third "classical" tongue emerged, Turkish, whose literature was based on Persian tradition.

— [21]

Toynbee's assessment of the role of the Persian language is worth quoting in more detail, from A Study of History:

In the Iranian world, before it began to succumb to the process of Westernization, the New Persian language, which had been fashioned into literary form in mighty works of art...gained a currency as a lingua franca; and at its widest, about the turn of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries of the Christian Era, its range in this role extended, without a break, across the face of South-Eastern Europe and South-Western Asia from the Ottoman pashalyq of Buda, which had been erected out of the wreckage of the Western Christian Kingdom of Hungary after the Ottoman victory at Mohacz in A.D. 1526, to the Muslim "successor-states" which had been carved, after the victory of the Deccanese Muslim princes at Talikota in A.D. 1565, out of the carcass of the slaughtered Hindu Empire of Vijayanagar. For this vast cultural empire the New Persian language was indebted to the arms of Turkish-speaking empire-builders, reared in the Iranian tradition and therefore captivated by the spell of the New Persian literature, whose military and political destiny it had been to provide one universal state for Orthodox Christendom in the shape of the Ottoman Empire and another for the Hindu World in the shape of the Timurid Mughal Raj. These two universal states of Iranian construction on Orthodox Christian and on Hindu ground were duly annexed, in accordance with their builders' own cultural affinities, to the original domain of the New Persian language in the homelands of the Iranian Civilization on the Iranian plateau and in the Basin of the Oxus and the Jaxartes; and in the heyday of the Mughal, Safawi, and Ottoman regimes New Persian was being patronized as the language of literae humaniores by the ruling element over the whole of this huge realm, while it was also being employed as the official language of administration in those two-thirds of its realm that lay within the Safawi and the Mughal frontiers.

— [45]

E. J. W. Gibb is the author of the standard A Literary History of Ottoman Poetry in six volumes, whose name has lived on in an important series of publications of Arabic, Persian, and Turkish texts, the Gibb Memorial Series.[46] Gibb classifies Ottoman poetry between the "Old School", from the 14th century to about the middle of the 19th century, during which time Persian influence was dominant; and the "Modern School", which came into being as a result of the Western impact. According to Gibb in the introduction (Volume I):

the Turks very early appropriated the entire Persian literary system down to its minute detail, and that in the same unquestioning and wholehearted fashion in which they had already accepted Islam.

The Saljuqs had, in the words of the same author:

attained a very considerable degree of culture, thanks entirely to Persian tutorage. About the middle of the eleventh century they [that is, the Saljuqs] had overrun Persia, when, as so often happened, the Barbarian conquerors adopted the culture of their civilized subjects. Rapidly the Seljuq Turks pushed their conquest westward, ever carrying with them Persian culture...[s]o, when some hundred and fifty years later Sulayman's son [the leader of the Ottomans]... penetrated into Asia Minor, they [the Ottomans] found that although Seljuq Turkish was the everyday speech of the people, Persian was the language of the court, while Persian literature and Persian culture reigned supreme. It is to the Seljuqs with whom they were thus fused, that the Ottomans, strictly so called, owe their literary education; this therefore was of necessity Persian as the Seljuqs knew no other. The Turks were not content with learning from the Persians how to express thought; they went to them to learn what to think and in what way to think. In practical matters, in the affairs of everyday life and in the business of government, they preferred their own ideas; but in the sphere of science and literature they went to school with the Persian, intent not merely on acquiring his method, but on entering into his spirit, thinking his thought and feeling his feelings. And in this school they continued so long as there was a master to teach them; for the step thus taken at the outset developed into a practice; it became the rule with the Turkish poets to look ever Persia-ward for guidance and to follow whatever fashion might prevail there. Thus it comes about that for centuries Ottoman poetry continued to reflect as in a glass the several phases through which that of Persia passed...[s]o the first Ottoman poets, and their successors through many a generation, strove with all their strength to write what is little else than Persian poetry in Turkish words. But such was not consciously their aim; of national feeling in poetry they dreamed not; poetry was to them one and indivisible, the language in which it was written merely an unimportant accident.

Persianate culture of South Asia

In general, from its earliest days, Persian culture was brought into the Subcontinent (or South Asia) by various Persianised Turkic and Afghan dynasties.[47] South Asian society was enriched by the influx of Persian-speaking and Islamic scholars, historians, architects, musicians, and other specialists of high Persianate culture who fled the Mongol devastation. The sultans of Delhi, who were of Turko-Afghan origin, modeled their lifestyles after the Persian upper classes. They patronized Persian literature and music, but became especially notable for their architecture, because their builders drew from Irano-Islamic architecture, combining it with Indian traditions to produce a profusion of mosques, palaces, and tombs unmatched in any other Islamic country.[26] The speculative thought of the times at the Mughal court, as in other Persianate courts, leaned towards the eclectic gnostic dimension of Sufi Islam, having similarities with Hindu Vedantism, indigenous Bhakti and popular theosophy.[48]

The Mughals, who were of Turco-Mongol descent, strengthened the Indo-Persian culture, in South Asia. For centuries, Iranian scholar-officials had immigrated to the region where their expertise in Persianate culture and administration secured them honored service within the Mughal Empire.[49]:24–32 Networks of learned masters and madrasas taught generations of young South Asian men Persian language and literature in addition to Islamic values and sciences. Furthermore, educational institutions such as Farangi Mahall and Delhi College developed innovative and integrated curricula for modernizing Persian-speaking South Asians.[49]:33 They cultivated Persian art, enticing to their courts artists and architects from Bukhara, Tabriz, Herat, Shiraz, and other cities of Greater Iran. The Taj Mahal and its Charbagh were commissioned by the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan for his Iranian bride.

Iranian poets, such as Sa’di, Hafez, Rumi and Nizami, who were great masters of Sufi mysticism from the Persianate world, were the favorite poets of the Mughals. Their works were present in Mughal libraries and counted among the emperors’ prized possessions, which they gave to each other; Akbar and Jahangir often quoted from them, signifying that they had imbibed them to a great extent. An autographed note of both Jahangir and Shah Jahan on a copy of Sa’di’s Gulestān states that it was their most precious possession.[50]:101, cat. no. 36 a.c A gift of a Gulestān was made by Shah Jahan to Jahanara Begum, an incident which is recorded by her with her signature.[50]:332.38, Cat. no. 136a.f Shah Jahan also considered the same work worthy enough to be sent as a gift to the king of England in 1628, which is presently in the Chester Beatty Library, Dublin. The emperor often took out auguries from a copy of the diwan of Hafez belonging to his grandfather, Humayun. One such incident is recorded in his own handwriting in the margins of a copy of the diwan, presently in the Khuda Bakhsh Oriental Library, Patna.[51] The court poets Naziri, ‘Urfi, Faizi, Khan-i Khanan, Zuhuri, Sanai, Qodsi, Talib-i Amuli and Abu Talib Kalim were all masters imbued with a similar Sufi spirit, thus following the norms of any Persianate court.[notes 2]

The tendency towards Sufi mysticism through Persianate culture in Mughal court circles is also testified by the inventory of books that were kept in Akbar’s library, and are especially mentioned by his historian, Abu'l Fazl, in the Ā’in-ī Akbarī. Some of the books that were read out continually to the emperor include the masnavis of Nizami, the works of Amir Khusrow, Sharaf Manayri and Jami, the Masnavi i-manavi of Rumi, the Jām-i Jam of Awhadi Maraghai, the Hakika o Sanā’i, the Qabusnameh of Keikavus, Sa’di’s Gulestān and Būstān, and the diwans of Khaqani and Anvari.[52][53]

This intellectual symmetry continued until the end of the 19th century, when a Persian newspaper, Miftah al-Zafar (1897), campaigned for the formation of Anjuman-i Ma’arif, an academy devoted to the strengthening of Persian language as a scientific language.[48]

Media of Persianate culture

Persian poetry (Sufi poetry)

From about the 12th century, Persian lyric poetry was enriched with a spirituality and devotional depth not to be found in earlier works. This development was due to the pervasive spread of mystical experience. Sufism developed in all Muslim lands, but its literary expression reached its zenith in the countries located within the sphere of Persian cultural influence. As a counterpoise to the rigidity of formal Islamic theology and law, mysticism sought to approach the divine through acts of devotion and love rather than through mere rituals and observance. Love of God being the focus of the Sufis' religious sentiments, it was only natural for them to express it in lyrical terms, and Persian mystics, often of exceptional sensibility and endowed with poetic verve, did not hesitate to do so. The famous 11th-century Sufi, Abu Sa'id of Mehna frequently used his own love quatrains (as well as others) to express his spiritual yearnings, and with mystic poets such as Attar and Iraqi, mysticism became a legitimate, even fashionable subject of lyric poems among the Persianate societies. Furthermore, as Sufi orders and centers (Khaneghah) spread throughout Persian societies, Persian mystic poetic thought gradually became so much a part of common culture that even poets who did not share Sufi experiences ventured to express mystical ideas and imagery in their work.[54]

Shi'ism

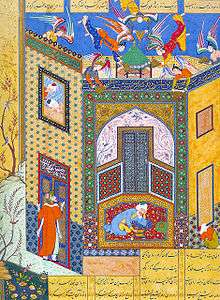

Persian painting

._Portrait_of_Fath_'Ali_Shah_Qajar%2C_1815.jpg)

Almost every Persian artwork was accompanied by texts. In the late 14th and 15th centuries, political control in Iran passed to the Timurids, who moved the capital from Tabriz in the west to Samarkand and Herat in the east. In the first half of the 15th century, Iranian artists working for the Timurid sultans developed the highly detailed, jewel-like style of painting that signifies Persian painting, which became known as the "Persian School of Herat".

When the Safavids came to power in 1501 and unified the eastern and western parts of Iran, the eastern and western Persian painting styles were mingled. The political unity under the first two Safavid rulers Ismail I and Tahmasp I, and the establishment of the Safavid capital at Tabriz in the west, led Persian artists to leave Herat. One of the most celebrated Iranian painters, Behzad, known as "the master of Persian painting", influenced many other Persian painters, including Reza Abbasi and Sultan Muhammad. He eventually painted perhaps the most extraordinary example of Persian painting The Court of the Gayumars from an opulent edition of the Shahnameh, commissioned by Shah Tahmasp c. 1522–1525. The painting depicts the legendary court of Gayumars, the first shah in the epic.

In Anatolia, a flourishing school of painting developed at the courts of Turkic rulers in the second half of the 15th century. The style of Ottoman miniature illustrations was derived from the Persian models, especially the painting of Shiraz.[55] The long reign of the Ottoman sultan Suleyman enabled his successor Selim (r. 1566–1574) to enjoy the pleasures of the palace without much concern for military conquests. A painting of Sultan Selim II in the exhibition depicts him partaking in one of his favorite pastimes, drinking, which earned him the nickname "Selim the Sot".[56]

By the mid-16th century, some Iranian artists from the Safavid Persian court had immigrated to Istanbul. Others had made their way to India in the retinue of the Mughal emperor Humayun, who returned to India in 1555 from exile in Iran. It was at the court of Humayun's son and successor Akbar (r. 1556–1605), however, that the Mughal style of painting came into its own.

The most important early project in this new style was the 14-volume Hamzanama produced by a team of Indian artists, both Muslim and Hindu, working under the supervision of Mir Sayyid Ali and Abd al-Samad, two Persian émigré artists. Akbari paintings incorporated the precise, linear style of Persian painting with the dynamism and vibrant palette of indigenous Indian painting. With the introduction of European-style perspective and modelling, Mughal painting became increasingly naturalistic from the 1580s until the mid-17th century, but the core of both Ottoman and Mughal painting remained Persian.

Persian music

Iranian celebrations of Nowruz and Chaharshanbeh-Suri

The term nowruz first appeared in Persian records in the 2nd century CE, but it was also an important day during Achaemenid times (c. 550–330 BCE), on which kings from different nations under Persian rule would present gifts to the emperor (Shahanshah) of Persia[5]. It has been suggested that the famous Persepolis complex, or at least the palace of Apadana and the "Hundred Columns Hall", were built for the specific purpose of celebrating Nowruz. However, no mention of Nowruz exists in Achaemenid inscriptions (see picture). Later it became the national holiday of the Parthian Empire, which ruled Iran (c. 247 BCE – 224 CE). There are specific references to the celebration of Nowruz during the reign of Vologases I (51–78 CE), but these include no details.

Extensive records on the celebration of Nowruz appear following the accession of Ardashir I of Persia, the founder of the Sasanian Empire (224–651 CE). Under the Sassanid kings, Nowruz was celebrated as the most important day of the year. Most royal traditions of Nowruz, such as audiences with the public, cash gifts, and the pardoning of prisoners, were established during the Sassanid era, and they persisted unchanged until modern times.

Nowruz, along with Sadeh (celebrated in mid-winter), survived in society following the introduction of Islam in 650 CE. Other celebrations such as Gahanbar and Mehregan were eventually side-lined or were only continued by the Zoroastrians, who carried them as far as Turkey. Nowruz, however, was honored even by the early founders of Islam. There are records of the Rashidun caliphs presiding over Nowruz celebrations and it was adopted as the main royal holiday during the Abbasid period.

Following the demise of the caliphate and the subsequent re-emergence of Persian dynasties such as the Samanids and Buyyids, Nowruz was elevated to an even higher status. The Buyids revived the Sassanid traditions and restored many smaller celebrations that had been eliminated by the caliphate. Even the Turkish and Mongol invaders did not attempt to abolish Nowruz in favor of any other celebration. Thus, Nowruz remained the main celebration of Persian lands by both the officials and the people.

Conclusion

As the broad cultural region remained politically divided, the sharp antagonisms between empires stimulated the appearance of variations of Persianate culture. After 1500, the Iranian culture developed distinct features of its own, with interposition of strong pre-Islamic and Shiite Islamic culture. Iran's ancient cultural relationship with Southern Iraq (Sumer/Babylonia) remained strong and endured in spite of the loss of Mesopotamia to the Ottomans. Its ancient cultural, genetic, historical relationship with the Caucasus endures to the present day, as is seen in Azerbaijan, Armenia, Georgia and parts of the North Caucasus, even after the loss of these regions to Imperial Russia following the Russo-Persian Wars in the course of the 19th century. The culture of peoples of the eastern Mediterranean in Anatolia, Syria, and Egypt developed somewhat independently; India developed a vibrant and completely distinct South Asian style with little to no remnants of the once patronized Indo-Persian culture by the Mughals.[57][58] culture; and Central Asia, which gradually grew more isolated, predominantly remains Persianised to this day; Ottoman Turkey developed differently and Turkish nationalism has developed since the formation of Turkey.

See also

References

- Arjomand, Said Amir (2004). Studies on Persianate Societies. ISBN 978-81-7304-667-4.

- Lawrence, Bruce B. (2009). "Islam in Afro-Eurasia: A Bridge Civilization". In Peter J. Katzenstein (ed.). Civilizations in World Politics: Plural and Pluralist Perspectives. Routledge. pp. 157–175. ISBN 978-0-203-87248-2.

Persianate is a new term, first coined by Marshall Hodgson to offer a different explanation of Islam in the world system than that extrapolated from Wallerstein. While Persianate depicts a cultural force that is linked to Persian language and to self-identifiying Persians, Persianate is more than either a language or a people; it highlights elements that Persians share with Indo-Aryan rulers who preceded Muslims to the subcontinent. Two elements are paramount: hierarchy ... (and) deference

- Hodgson, Marshall G. S. (1974). The Venture of Islam. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Özgündenli, O. "Persian Manuscripts in Ottoman and Modern Turkish Libraries". Encyclopaedia Iranica (online ed.).

- Luther, K.A. "Alp Arslān". Encyclopaedia Iranica (online ed.).

Saljuq activity must always be viewed both in terms of the wishes of the sultan and his Khorasanian, Sunni advisors, especially Nezām-al-molk ...

- "Seljuq". Encyclopædia Britannica (online ed.).

Because the Turkish Seljuqs had no Islamic tradition or strong literary heritage of their own, they adopted the cultural language of their Persian instructors in Islam. Literary Persian thus spread to the whole of Iran, and the Arabic language disappeared in that country except in works of religious scholarship

- "Timurids". The Columbia Encyclopedia (Sixth ed.). New York City: Columbia University. Archived from the original on 2006-12-05. Retrieved 2006-11-08.

- David J. Roxburgh. The Persian Album, 1400–1600: From Dispersal to Collection. Yale University Press, 2005. pg 130: "Persian literature, especially poetry, occupied a central role in the process of assimilation of Timurid elite to the Perso-Islamicate courtly culture, and so it is not surprising to find Baysanghur commissioned a new edition of Firdawsi's Shanameh"

- Lehmann, F. "Zaher ud-Din Babor – Founder of Mughal empire". Encyclopaedia Iranica (Online ed.). New York City: Columbia University Center for Iranian (Persian) Studies. pp. 320–323. Archived from the original on 2007-10-13. Retrieved 2006-11-07.

His origin, milieu, training, and culture were steeped in Persian culture and so Babor was largely responsible for the fostering of this culture by his descendants, the Mughals of India, and for the expansion of Persian cultural influence in the Indian subcontinent, with brilliant literary, artistic, and historiographical results

- "Indo-Persian Literature Conference: SOAS: North Indian Literary Culture (1450–1650)". SOAS. Retrieved 28 November 2012.

- Özgündenli, O. "Persian Manuscripts in Ottoman and Modern Turkish Libraries". Encyclopaedia Iranica (online ed.).

- "Persian in service of the state: the role of Persophone historical writing in the development of an Ottoman imperial aesthetic", Studies on Persianate Societies, 2, 2004, pp. 145–63

- "Historiography. xi. Persian Historiography in the Ottoman Empire". Encyclopaedia Iranica. 12, fasc. 4. 2004. pp. 403–11.

- Walter, F. "7. The Departure of Turkey from the 'Persianate' Musical Sphere". Music of the Ottoman court.

- Euben, R. L. (1999). Enemy in the Mirror: Islamic Fundamentalism and the Limits of Modern Rationalism: A Work of Comparative Political Theory. Princeton, USA: Princeton University Press.

- Canfield, Robert (1991). Turko-Persia in historical perspective. Cambridge University Press.

- Shahbazi, A. Shapur (2006). "Sassanian Dynasty". Encyclopaedia Iranica (online ed.). Archived from the original on 2010-01-09.

- Boyce, Mary (1967). Bībī Shahrbānū and the Lady of Pārs. BSOAS. p. 30.

- Boyce, Mary (December 1989). "Bibi Sahrbanu". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- Frye, R.N. (1975). The Golden Age of Persia: The Arabs in the East. London and New York: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

- Hodgson, Marshall G. S. (1974). "The Expansion of Islam in the Middle Periods". The Venture of Islam. 2. Chicago, USA. p. 293.

- Arjomand, Said Amir (2008). "From the Editor: Defining Persianate Studies". Journal of Persianate Studies. 1 (4): 2.

- Lentz, T. W.; Lowry, G. D. (1989). Timur and the Princely Vision: Persian Art and Culture in the Fifteenth Century. Washington, DC, USA: Smithsonian Press. p. 126.

- Chambers, R. L. (2000). The Ottoman Empire; a Chronological Outline. University of Chicago.

- Daftary, F. "Sectarian and National Movements in Iran, Khorasan, and Trasoxania during Umayyad and Early Abbasid Times". In M.S. Asimov; C.E. Bosworth (eds.). History of Civilizations of Central Asia. 4–1. UNESCO Publishing, Institute of Ismaili Studies.

- Ikram, S. M (1964). Muslim Civilization in India. New York, USA: Columbia University Press.

- Woodhead, C. (1983). "An Experiment in Official Historiography: The Post of Sehnameci in the Ottoman Empire, c. 1555–1605". Wiener Zeitschrift für die Kunde des Morgenlandes. 75: 174.

- Murtazavi, Manuchihr. "Muqallidan-i Shahnamah dar dawrah-yi Mughul va Timuri". Masa'il-i 'asr-i Ilkhanan. Tabriz: Mu'assasah-i Tarikh va Farhang-i Iran, SH/1358. pp. 554–555.

- Meisami, Julie S. (1999). Persian Historiography to the End of the Twelfth Century. Edinburgh, UK: Edinburgh University Press. p. 37.

- "aksi az ru-yi nuskhah-i khatti-i muvarrakh-i AH/807, dar Kitabkhanah-i Biritaniya (Or. 2833)". Zafarnamah-i Hamd Allah Mustawfi: bi-inzimam-i Shahnamah-i Abu al-Qasim Firdawsi (bih tashih-i Hamd Allah Mustawfi). Tehran, Iran: Markaz-i Nashr-i Danishgahi-i Iran; Vin: Akadimi-i ‘Ulum-i Utrish. 1999.

- Rypka. History of Iranian Literature. p. 165.

- Molé, Marjan (1953). L'épopée iranienne après Firdosi. La Nouvelle Clio 5. pp. 377–393.

- Safa, Z. (1990). Hamasahsarayi dar Iran. Tehran, Iran: Amir Kabir.

- Quint, D. (1993). Epic and Empire: Politics and Generic Form from Virgil to Milton. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 15.

- Seyller, John (2001). Pearls of the Parrot of India: The Walters Art Museum Khamsa of Amir Khusraw of Delhi. Baltimore, USA: Walters Art Museum. pp. 143–58.

- Savory, Roger M. (2005). "Safawids". Encyclopaedia of Islam (online ed.).

- Savory, Roger M. (1965). "The consolidation of Safawid power in Persia". Isl.

- "Persien (Geschichte des neupersischen Reichs)". Meyers Konversations-Lexikon (in German). XII. p. 873.

- Savory, R.M. (1980). Iran under the Safavids. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 3.

- Hillenbrand, R. (1999). Islamic art and Architecture. London, UK. ISBN 978-0-500-20305-7.

- Titley, Norah M. (1983). Persian Miniature Painting and its Influence on the Art of Turkey and India. Austin, USA: University of Texas.

- Yarshater, Ehsan (1988). "The development of Iranian literatures". In Ehsan Yarshater (ed.). Persian Literature. Columbia Lectures on Iranian Studies. 3–37. Albany, USA: Bibliotheca Persica and State University of New York. p. 15.

- Yazıcı, Tahsin. "Čelebi". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Archived from the original on November 18, 2007. Retrieved February 10, 2007.

- Halman, Talat S. "Suleyman the Magnificent Poet".

- Toynbee, Arnold J. A Study of History. V. pp. 514–15.

- "GIBB MEMORIAL SERIES – Encyclopaedia Iranica". www.iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2020-01-27.

- Sigfried J. de Laet. History of Humanity: From the seventh to the sixteenth century UNESCO, 1994. ISBN 978-9231028137 p 734

- Rizvi, S. (1993). "Chapter 1". Muslim Revivalist Movements in Northern India in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries. New Delhi, India.

- Fisher, M. H. (2001). "Persian Professor in Britain: Mirza Muhammad Ibrahim at the East India Company's College, 1826–44". Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East. Duke University Press. 21 (1–2): 24–32. doi:10.1215/1089201X-21-1-2-24.

- Soudavar. Art of the Persian Courts.

- Prince Khurram's (Shahjahan) own specimen of calligraphic verses of Hafiz is in the Rampur Raza Library, Rampur (hereafter RL) (Siddiqi, Rampur Raza Library: pl. 24).

- Browne, E.G. (1951). A Literary History of Persia. II and III. Cambridge.

- Arberry, A.J. (1958). Classical Persian Literature. London.

- "The Development of Persian Poetry". Iransaga.

- "Persianate Sources on Anatolia and the Early History of the Ottomans". Studies on Persianate Societies. 2. 2004. pp. 126–44.

- "Selim II | Ottoman sultan". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-01-27.

- Shamil, S. (2004). "The City of Beauties in Indo-Persian Poetic Landscape". Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East. Duke University Press. 24.

- Delvoye, F. (1996). "Music in the Indo-Persian Courts of India (14th–18th century)". Studies in Artistic Patronage. The International Institute for Asian Studies (IIAS).

Notes

- Hodgson says, "It could even be said that Islamicate civilization, historically, is divisible in the more central areas into an earlier 'caliphal' and a later 'Persianate' phase; with variants in the outlying regions—Maghrib, Sudanic lands, Southern Seas, India,... (p. 294)"

- For the influence of Rumi's poetry on contemporary poetics, see Schimmel, The Triumphal Sun: 374.78; for Mughal poetry, see Ghani, A History of Persian Language and Literature; Rahman, Persian Literature; Hasan, Mughal Poetry; Abidi, .Tālib-I Āmulī; idem, .Qudsi Mashhadi.; Nabi Hadi, Talib-i Amuli; Browne, A Literary History, vol. IV: 241.67.