Savannasaurus

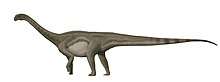

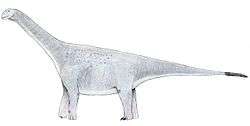

Savannasaurus is a genus of titanosaurian sauropod dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous Winton Formation of Queensland, Australia, containing one species, Savannasaurus elliottorum, named in 2016 by Poropat et al.[2] The only known specimen was originally nicknamed "Wade".[3][4] The holotype is held on display at the Australian Age of Dinosaurs museum.

| Savannasaurus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Skeleton | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Suborder: | †Sauropodomorpha |

| Clade: | †Sauropoda |

| Clade: | †Titanosauria |

| Genus: | †Savannasaurus Poropat et al. 2016 |

| Species: | †S. elliottorum |

| Binomial name | |

| †Savannasaurus elliottorum Poropat et al. 2016 | |

Description

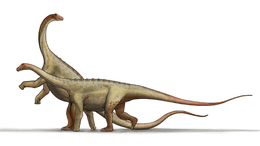

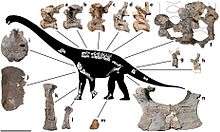

Savannasaurus was a medium-sized titanosaur about 15 metres (49 ft) in length.[4] The sacrum and the fused ischium-pubis complex are both over one metre in width at their narrowest points, making Savannasaurus an unusually wide-bodied titanosaur. In addition to this, the describers identified several other distinguishing characteristics: the first few caudal vertebrae have shallow pits, or fossae, in their sides, a feature that was previously only known among brachiosaurids; the edges of the sternal plates are straight, not kidney-shaped like other titanosaurs; the end of the fourth metacarpal is hourglass-shaped; there is a ridge on the side of the pubis extending forward and downward from the obturator foramen; and the astragalus is taller than it is wide or long.[2]

As with other titanosauriforms, the internal texture of the vertebrae is pneumatized by many small holes (camellate), and the dorsal ribs also bear pneumatic cavities. The dorsal vertebrae have ridges on the sides of their bottom faces as in Diamantinasaurus and Opisthocoelicaudia, but Savannasaurus lacks the keel on the bottom of the dorsal vertebrae as in these species; the dorsal neural spines are also not split into two, unlike Opisthocoelicaudia. The known cervical vertebrae and dorsal vertebrae are opisthocoelous, while all of the caudal vertebrae are amphicoelous unlike most other titanosaurs.[2]

Discovery and naming

The holotype specimen of Savannasaurus, AODF 660, was discovered in 2005 on the Belmont sheep station by David Elliot, founder of Australian Age of Dinosaurs. The Belmont sheep station, northeast of Winton, Queensland, is part of the upper Winton Formation which has been dated to the Cenomanian-early Turonian based on detritial zircons.[1] One of the holotype's metatarsals was originally thought to have belonged to a theropod, but later excavations revealed the remainder of the skeleton.[4] The specimen consists of several cervical, dorsal, sacral, and caudal vertebrae, several ribs, portions of the shoulder girdle including a coracoid and both sternal plates, parts of the forelimbs including the feet, several elements of the hip, and bones from the hind foot, along with various fragments. The specimen was encased in a single concretion.[2]

The genus name of Savannasaurus, from Spanish sabana ("savanna"), refers to the environment in which it was found. The species name honours the Elliott family and their contributions to Australian palaeontology.[2]

Phylogeny

A phylogenetic analysis conducted in 2016 found Savannasaurus to be closely related to the contemporaneous Diamantinasaurus, as a non-lithostrotian titanosaur.[2]

| Titanosauria |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleoecology

Savannasaurus lived alongside a diverse vertebrate fauna in the upper Winton Formation,[1] that included its close relative Diamantinasaurus, other sauropods Wintonotitan and Austrosaurus, the megaraptoran theropod Australovenator, ankylosaurians, and hypsilophodonts, along with the lungfish Metaceratodus, turtles, the crocodilian Isisfordia, and pterosaurs. The environment it lived in would have been populated by plants such as ferns, ginkgoes, gymnosperms, and angiosperms.[5]

See also

References

- Tucker, R.T.; Roberts, E.M.; Hu, Y.; Kemp, A.I.S.; Salisbury, S.W. (2013). "Detrital zircon age constraints for the Winton Formation, Queensland: Contextualizing Australia's Late Cretaceous dinosaur faunas". Gondwana Research. 24 (2): 767–779. doi:10.1016/j.gr.2012.12.009.

- Poropat, S.F.; Mannion, P.D.; Upchurch, P.; Hocknull, S.A.; Kear, B.P.; Kundrát, M.; Tischler, T.R.; Sloan, T.; Sinapius, G.H.K.; Elliott, J.A.; Elliott, D.A. (2016). "New Australian sauropods shed light on Cretaceous dinosaur palaeobiogeography". Scientific Reports. 6: 34467. doi:10.1038/srep34467. PMC 5072287. PMID 27763598.

- St. Fleur, Nicholas (20 October 2016). "Meet the New Titanosaur. You Can Call It Wade". New York Times. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

- Geggel, Laura (2016). "Wide-Hipped Dinosaur the Size of a Bus Once Trod Across Australia". Live Science. Purch.

- Hocknull, Scott A.; White, Matt A.; Tischler, Travis R.; Cook, Alex G.; Calleja, Naomi D.; Sloan, Trish; Elliott, David A. (2009). Sereno, Paul (ed.). "New Mid-Cretaceous (Latest Albian) Dinosaurs from Winton, Queensland, Australia". PLoS ONE. 4 (7): e6190. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0006190. PMC 2703565. PMID 19584929.