Chinshakiangosaurus

Chinshakiangosaurus (JIN-shah-jiahng-uh-SOR-us, meaning "Chinshakiang lizard") is a genus of dinosaur and probably one of the most basal sauropods known. The only species, Chinshakiangosaurus chunghoensis, is known from a fragmentary skeleton found in Lower Jurassic rocks in China. Chinshakiangosaurus is one of the few basal sauropods with preserved skull bones and therefore important for the understanding of the early evolution of this group. It shows that early sauropods may have possessed fleshy cheeks.[1]

| Chinshakiangosaurus | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Suborder: | †Sauropodomorpha |

| Clade: | †Sauropoda |

| Genus: | †Chinshakiangosaurus Dong, 1992 |

| Species: | †C. chunghoensis |

| Binomial name | |

| †Chinshakiangosaurus chunghoensis Dong, 1992 | |

Description and feeding

Like all sauropods, it was a large, quadrupedal herbivore with long neck and tail. The body length of the only specimen is estimated at 12 to 13 meters.[2] The remains consists of the dentary (the tooth bearing bone of the mandible) including teeth as well as several parts of the postcranium. By now, only the dentary and the teeth were studied extensively; the remaining skeleton still awaits a proper description.[1]

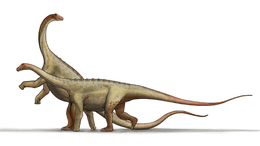

The dentary was curved in dorsal view, so that the mandibles formed a U-shaped, broad snout. This feature is typical for sauropods – in Prosauropods, on the contrary, the dentary was straight, forming a V-shaped, tapered snout. Paul Upchurch and colleagues (2007) suppose that this differences can give hints about feeding habits: The prosauropods with their tapered snouts possibly where selective feeders, who ate only certain plant parts, whereas sauropods with their broad snouts where bulk feeders, adapted to consume large amounts of foliage.[1]

The tooth size increased towards the tip of the snout, like in sauropods. Another derived, sauropod like feature was a bony plate that lined the tooth row laterally and became thicker towards the tip of the snout. This plate may have hindered the teeth to be displaced while defoliating plants.[1]

The dentary was deep. However, as in prosauropods, it became lower towards the tip of the snout, while in sauropods the dentary became deeper, forming a very deep symphysis.[1][3] In lateral view, the dentary shows a prominent ridge running diagonally across the bone. Apart from Chinshakiangosaurus, this feature is only known from prosauropods, where it is interpreted as the insertion point of a fleshy cheek.[1][4] Such cheeks would have prohibited food falling out of the mouth and may be a hint that the food underwent some degree of oral processing before it was swallowed. If Chinshakiangosaurus indeed was a basal sauropod, this would be the first evidence of cheeks in this group. In all other sauropods known from congruous remains this feature had been reduced already.[1]

On each side of the mandible there were 19 teeth – more than in all known sauropods, but fewer than in the prosauropod Plateosaurus. The teeth were lanceolate and furnished with coarse denticles; therewith they resemble those of prosauropods more than those of sauropods. However, the lingual side of the teeth already was slightly concave, possibly an initial state towards the strongly concave, spoon shaped teeth that were typical for sauropods.[1]

Classification

|

Initially, Dong Zhiming classified Chinshakiangosaurus as a member of the Melanorosauridae, which he thought to be a group of prosauropods. However, he already noted certain resemblances with sauropods.[2] More recent studies classify this genus as a very basal sauropod.[1][5][6] The exact relationships are not clear, though.[1]

Discovery

The fossils were found in 1970 by Zhao Xijin and colleagues in Yongren County[7] in central Yunnan. They come from the Fengjiahe Formation, which is made up of mudstones, siltstones and sandstones that were deposited fluvolacustrine (inside rivers and lakes). Fossils of Invertebrates like ostracodes and bivalves were used to determine these sediments as Upper Jurassic in age. A more precise dating could not be made.[1]

The holotype specimen (IVPP V14474) consists of a left dentary, one cervical and several dorsal and caudal vertebrae, both scapulae, some pelvic bones and the hind limbs. C. H. Ye mentioned this specimen in 1975 under the name Chinshakiangosaurus chunghoensis (after the Yangtze River and the village Zhonghe). However, because he did not provide a description of the fossils, the name was a Nomen nudum (nacked name) until Dong Zhiming published a short description in 1992.[1][2] Since then, the authorship is correctly cited as "Chinshakiangosaurus chunghoensis Ye vide Dong, 1992".[1]

After Dongs description, this genus, though potentially valid, remained unnoticed by most paleontologists. It was mentioned by Upchurch and colleagues (2004), who classified it as a nomen dubium inside Sauropoda.[6] In 2007, Upchurch and colleagues published a comprehensive description of the dentary and the teeth and declared Chinshakiangosaurus as a valid taxon.[1]

References and Notes

- Upchurch, P.; P. M. Barrett; Z. Xijin; X. Xing (2007). "A re-evaluation of Chinshakiangosaurus chunghoensis Ye vide Dong 1992 (Dinosauria, Sauropodomorpha): implications for cranial evolution in basal sauropod dinosaurs". Geological Magazine. 144 (2): 247–262. doi:10.1017/S0016756806003062. Archived from the original on 2013-01-12. Retrieved 2012-09-24.

- Dong, Zhiming; Chih-ming Tung (1992). Dinosaurian faunas of China. China Ocean Press. ISBN 9783540520849.

- Buffetaut, E. (2005). "A new sauropod dinosaur with prosauropod-like teeth from the Middle Jurassic of Madagascar". Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France. 176 (5): 467–473. Retrieved 2012-09-24.

- Galton, Peter M.; Paul Upchurch; P. Dodson (2004). "Prosauropoda". In D. B. Weishampel; H. Osmolska (eds.). The Dinosauria (2. ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 232–258. ISBN 978-0-520-25408-4.

- Bandyopadhyay, Saswati; David D. Gillette; Sanghamitra Ray; Dhurjati P. Sengupta (2010). "Osteology of Barapasaurus tagorei (Dinosauria: Sauropoda) from the Early Jurassic of India". Palaeontology. 53 (3): 533–569. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2010.00933.x. ISSN 1475-4983.

- Upchurch, Paul; Paul M. Barret; Peter Dodson; P. Dodson (2004). "Sauropoda". In D. B. Weishampel; H. Osmolska (eds.). The Dinosauria (2. ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 259–322. ISBN 978-0-520-25408-4.

- in Upchurch et al. 2007 stated that the fossils were found in "Yungyin County"; however, based on the coordinates "26.2° North, 101.4° East", it can be identified as Yongren County.