Ohmdenosaurus

Ohmdenosaurus ("Ohmden lizard") is a genus of herbivorous dinosaur from the Lower or Middle Toarcian age of the Early Jurassic in what is now Ohmden, Germany. It is one of the earliest European sauropods. It is also one of the few sauropods described from the Toarcian of the modern Northern Hemisphere, along with Tazoudasaurus, which may be a relative. Ohmdenosaurus lived on an island series in what is now the region of Bohemia. Its fossils were originally described as plesiosaur remains, until a revision of the holotype in 1978 identified them as sauropod fossils. It is the only dinosaur identified from the Posidonia Shale.[1]

| Ohmdenosaurus | |

|---|---|

| Fossil tibia and astragalus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Suborder: | †Sauropodomorpha |

| Clade: | †Sauropoda |

| Genus: | †Ohmdenosaurus |

| Species: | †O. liasicus |

| Binomial name | |

| †Ohmdenosaurus liasicus Wild, 1978 | |

Description

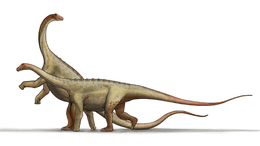

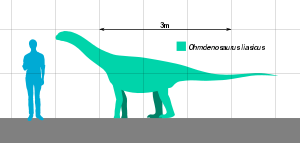

Ohmdenosaurus was a primitive sauropod. It was an obligate quadruped, with a relatively short neck and robust body. Like all sauropods, it was herbivorous. Ohmdenosaurus most likely fed on plants included in Bennettitales, Araucariaceae, and Podocarpaceae.[1] The type specimen of Ohmdenosaurus consists of a tibia and a talus bone (astragalus). The tibia is approximately 405 millimetres (15.9 in) long[1][2] with an estimated femur length of at least 70 centimetres (28 in). This yields an estimated total body length of 4 m (13 ft), which is relatively small for a sauropod.[1][3] A re-evaluation of Ohmdenosaurus' size suggests a body length of 6.7 metres (22 ft) and a weight of 1.3 tonnes (2,900 lb).[4] The small size of Ohmdenosaurus has led to speculation that the taxon may be one of the few examples of insular dwarfism among sauropods, much like the German Late Jurassic macronarian Europasaurus.[5] Alternatively, the holotype of Ohmdenosaurus may represent the remains of a juvenile individual.[6][7]

History of discovery

In the 1970s, German paleontologist Rupert Wild, visiting the Urwelt-Museum Hauff at Holzmaden in Baden-Württemberg, noticed a fossil in a display labelled as an upper arm bone of a plesiosaur which he recognized as a misidentified dinosaur fossil.[1] The bone had been collected from one of the early quarries near Ohmden that was later refilled. Although the exact discovery site is unknown, rock attached to the lower end of the fossil comes from the unterer Schiefer ("lower slate"), or the oldest part of the Posidonia Shale.[1] It is therefore Early Toarcian in age (182.0 to 175.6 mya).[8] Further study determined that the fossil belonged to a new genus and species of early sauropod, which Wild named Ohmdenosaurus liasicus in a 1978 publication. The fossil, which lacks an inventory number, consists of a right tibia (shinbone) together with the upper bones of the ankle, the astragalus and the calcaneus. The bones, disarticulated in the fossil, show signs of weathering, evidence that the animal died on land and that only later were its bones washed into the sea and buried.

Classification

The shape of the astragalus—which is not convex on top as it is in derived members of Neosauropoda—suggests that Ohmdenosaurus was a very basal sauropod. However, with recent discoveries in Lessemsauridae, Ohmdenosaurus may be less basal than previously thought and more closely related to gravisaurians. In 1990, John Stanton McIntosh included Ohmdenosaurus in the Vulcanodontidae[9] along with the controversial genus Zizhongosaurus, though the study was based more heavily on the geological age of the two sauropods (Toarcian) rather than a comparative study of their morphologies.[3] The clade Vulcanodontidae has since become a wastebasket taxon for many unrelated basal sauropods, rendering this classification invalid and leaving Ohmdenosaurus' position still unclear. Recent studies have suggested that Ohmdenosaurus is a more basal gravisaurian, closely related to the Australian genus Rhoetosaurus. This reassignment of Ohmdenosaurus was proposed based on a range of features, including the presence of proximal and distal surfaces of the astragalus, and the presence of a rounded cnemial crest nearly identical on Rhoetosaurus. Similar astragalus morphology is also present in Ferganasaurus.[10]

Gravisaurian remains were discovered in 2015 from the Toarcian of Northern Germany, though they are likely distinct from Ohmdenosaurus as they bear more similarity to Tazoudasaurus than Rhoetosaurus.[11]

Paleoenvironment

Based on the paleogeography of the fossils, the early Jurassic sauropods occur more in middle latitudes, with a probably Tethyan distribution, rather than at higher latitudes.[12] Ohmdenosaurus is one of the few body fossil sauropod remains found in Europe. During the Toarcian, the Posidonia Shale extended along a mostly marine basin, with the main terrestrial environments of the Posidonia Shale being the near emerged lands, mostly of Paleozoic Origin, such as London-Brabant Massif at the west, the French Central Massif at the south, and the Vindelician High and Bohemian Massif at the east. Minor lands were present whose emerged nature on the Toarcian is controversial, including the Vlotho Massif at the northwest, the Swedish Bern high at the south, Rhenish Massif on the Center and the Fuenen High in the north.[13] The bones of Ohmdenosaurus are believed to have come from the Vindelician High or the connected Bohemian Massif. The landmass had an extension similar to modern Ireland, with an island environment, part of the coast called Vindelician Land, composed of large seashore environments, including River Deltas, Mangroves, Lagoons, and brackish water. The strata of the nearshore environments are populated by charcoal, which suggests a wide presence of fires.[14] The environments were influenced by monsoonal conditions and large scale rains that hit most of the nearshore settings, causing the large accumulation of insect remains found on the epicontinental layers. Southern summers with humid south-west monsoonal conditions occurred on most of the emerged lands, resulting in winters with dry north east trade winds. These were related to the seasonal occurrence of wood rafts on the formation and linked to the lifecycle of the stem crinoids. The joining of land, probably where the main source of seeds were located, helped to interchange species between landmasses.[15]

The terrestrial environments were populated by a large variety of flora, including Equisetaceae, Osmundaceae, Umkomasiaceae, Bennettitales, Araucariaceae, Cupressaceae and Podocarpaceae.[16][17] The fauna was dominated by a high variety of insect genera.[18] The only terrestrial or semi-terrestrial vertebrates other than Ohmdenosaurus conclusively discovered in the region are Pterosaurs, especially the island insectivore Campylognathoides and the more marine Dorygnathus. Testudinatans were reported on the 1800s,[19] although now are lost.[20] Other marine animals found include Teleosauridae, such as Platysuchus or the marine sphenodont Palaeopleurosaurus. A possible Trithelodontidae cynodont was cited in 19th century papers, but its presence has not been proven.[21]

References

- Wild, R. (1978). "Ein Sauropoden-Rest (Reptilia, Saurischia) aus dem Posidonienschiefer (Lias, Toarcium) von Holzmaden". Stuttgarter Beiträge zur Naturkunde, Serie B (Geologie und Paläontologie) (in German). 41: 1–15.

- Carrano, M.T. (1998). "The evolution of dinosaur locomotion: biomechanics, functional morphology, and modern analogs (Ph.D. thesis)". University of Chicago.

- Upchurch, P. (1995). "The evolutionary history of sauropod dinosaurs". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences. 349 (1330): 365–390. doi:10.1098/rstb.1995.0125.

- Molina-Pérez, R.; Larramendi, A. (2020). Dinosaur Facts and Figures: The Sauropods and Other Sauropodomorphs. Translated by Donaghey, J. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-19069-0. OCLC 1125972915.

- Großmann, F. (2006). Taxonomy, Phylogeny and Palaeoecology of the Plesiosauroids (Sauropterygia, Reptilia) from the Posidonia Shale (Toarcian, Lower Jurassic) of Holzmaden, South West Germany: Dissertation. Zur Erlangung Des Grades Eines Doktors Der Naturwissenschaften. p. 135. Geowissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Eberhard-Karls-Universität.

- Farlow, J.O.; Brett-Surman, M.K. (1997). Brett-Surman, M.K.; Holtz, Jr., T.R. (eds.). The Complete Dinosaur. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. p. 264. ISBN 0-253-33349-0. OCLC 37107117.

- Holtz, Jr., T.R.; Rey, L.V. (2007). Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-To-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-375-82419-7.

- Wild, R. (1978). "Ohmdenosaurus liasicus". paleobiodb.org. Paleobiology Database. Retrieved 2019-08-04.

- McIntosh, J.S. (1990). "Sauropoda". In Weishampel, D.B.; Dodson, P.; Osmólska, H. (eds.). The Dinosauria. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 345–401. ISBN 0-520-06726-6. OCLC 20670312.

- Nair, J. P., & Salisbury, S. W. (2012). New anatomical information on Rhoetosaurus brownei Longman, 1926, a gravisaurian sauropodomorph dinosaur from the Middle Jurassic of Queensland, Australia. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 32(2), 369–394.

- Stumpf, S.; Ansorge, J.; Krempien, W. (2015). "Gravisaurian sauropod remains from the marine late Early Jurassic (Lower Toarcian) of North-Eastern Germany". Geobios. 48 (3): 271–279. doi:10.1016/j.geobios.2015.04.001. ISSN 0016-6995.

- Gillette, D.D. (2003). "The geographic and phylogenetic position of sauropod dinosaurs from the Kota formation (Early Jurassic) of India". Journal of Asian Earth Sciences. Geology of the Pranhita-Godavari Valley , India. 21 (6): 683–689. doi:10.1016/S1367-9120(02)00170-0. ISSN 1367-9120.

- Lézin, C.; Andreu, B.; Pellenard, P.; Bouchez, J-L.; Emmanuel, L.; Fauré, P.; Landrein, P. (2013). "Geochemical disturbance and paleoenvironmental changes during the Early Toarcian in NW Europe". Chemical Geology. 341: 1–15. doi:10.1016/j.chemgeo.2013.01.003. ISSN 0009-2541.

- von Ammon, L. (1875). Die Jura-Ablagerungen zwischen Regensburg und Passau: Eine Monographie des niederbayerischen Jurabezirkes mit dem Keilberger Jura, unter besonderer Berücksichtigung seiner Beziehungen zum Frankenjura. Ackermann.

- Röhl, H-J.; Schmid-Röhl, A.; Oschmann, W.; Frimmel, A.; Schwark, L. (2001). "The Posidonia Shale (Lower Toarcian) of SW-Germany: an oxygen-depleted ecosystem controlled by sea level and palaeoclimate". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 165 (1): 27–52. doi:10.1016/S0031-0182(00)00152-8. ISSN 0031-0182.

- Wilde, V. (2001). "Die Landpflanzen-Taphozönose aus dem Posidonienschiefer des Unteren Jura (Schwarzer Jura [Epsilon], Unter-Toarcium) in Deutschland und ihre Deutung". Stuttgarter Beiträge zur Naturkunde.

- Prauss, M.; Ligouis, B.; Luterbacher, H. (1991). "Organic matter and palynomorphs in the 'Posidonienschiefer' (Toarcian, Lower Jurassic) of southern Germany". Geological Society, London, Special Publications. 58 (1): 335–351. doi:10.1144/GSL.SP.1991.058.01.21. ISSN 0305-8719.

- Ansorge, J. (2003). "Insects from the Lower Toarcian of Middle Europe and England" (PDF). Acta Zoologica Cracoviensia. 46: 291–310.

- Münster, G. (1836). "Mitteilungen an Professor Bronn gerichtet". Neues Jahrbuch für Mineralogie, Geognosie, Geologie und Petrefaktenkunde. 1836: 580–583.

- Joyce, W.G. (2017). "A Review of the Fossil Record of Basal Mesozoic Turtles". Bulletin of the Peabody Museum of Natural History. 58 (1): 65–113. doi:10.3374/014.058.0105. ISSN 0079-032X.

- Münster, G. (1836). "Letter on various fossils". Neues Jahrbuch für Mineralogie, Geognosie, Geologie und Petrefaktenkunde. 1836: 580–583.