Klamelisaurus

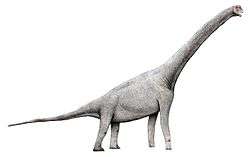

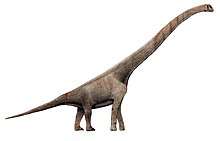

Klamelisaurus is a genus of herbivorous sauropod dinosaur from the Middle Jurassic Shishugou Formation of China. The type species is Klamelisaurus gobiensis, which was named by Zhao Xijin in 1993.[1]

| Klamelisaurus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Skeleton cast | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Suborder: | †Sauropodomorpha |

| Clade: | †Sauropoda |

| Genus: | †Klamelisaurus Zhao, 1993 |

| Species: | †K. gobiensis |

| Binomial name | |

| †Klamelisaurus gobiensis Zhao, 1993 | |

Discovery and naming

Between 1981 and 1985, a field crew from the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (IVPP) conducted excavations in the Junggar Basin of the Xinjiang Autonomous Region of China, as part of a research project titled "Evolution of the Junggar Basin and the Formation of Petroleum". The work was conducted in cooperation with the Chinese Academy of Sciences and the Xinjiang Office of Petroleum.[1] In 1982, these excavations uncovered the skeleton of a sauropod dinosaur 35 kilometres (22 mi) north of the now-abandoned town of Jiangjunmiao, located in the eastern Junggar Basin. The skeleton was excavated and collected in 1984 by the IVPP field team.[2]

The specimen, which was subsequently catalogued under the specimen number IVPP V9492, consists of teeth, most of the vertebral column (except for the first seven cervical vertebrae (neck vertebrae) and the end of the tail), ribs, the right shoulder girdle and arm (scapula, coracoid, humerus, ulna, radius, and phalanges), and the right hip girdle and leg (ilium, pubis, femur, tibia, fibula, and astragalus). At the time of its discovery, the specimen was already weathered. After it was transported to Beijing, with preparation and restoration work beginning in 1985, it deteriorated further due to fluctuations in temperature and humidity.[1] Nearly all of the bones underwent some reconstruction and painting, and many of them were encased in a metal armature for display. The referral of the fragmentary teeth to the specimen was unexplained, and they can no longer be located along with two ribs, two carpals of the wrist, a calcaneum of the ankle, and some bones of the tail. They also located several four chevrons (bones on the underside of the tail), the bottom end of the left femur, and parts of the left hand that were not mentioned by Zhao.[2]

In 1993, Xijing Zhao described IVPP V9492 as the type specimen of a new genus and species, Klamelisaurus gobiensis. Due to the condition of the specimen, he only conducted a "simple description". The generic name Klamelisaurus refers to the Kelameili Mountains to the north of Jiangjunmiao, of which "Klameli" is a variant spelling. The specific name gobiensis refers to the Gobi Desert, in which Jiangjunmiao is located.[1] Following Zhao's description, IVPP V9492 received limited attention in the literature until it was redescribed by Andrew Moore and colleagues in 2020. They noted that the specimen's reconstruction had been altered since Zhao's description, namely by the addition of a frontward-projecting process on the 15th cervical rib and the removal of a fabricated connection to the centrum (vertebral body).[2]

Description

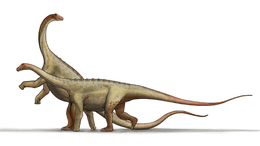

Klamelisaurus was described as a "relatively large" sauropod by Zhao in 1993.[1] In 2016, American paleontologist Gregory S. Paul estimated its length at 13 metres (43 ft) in length and 6 tonnes (5.9 long tons; 6.6 short tons) in weight, albeit based on the hypothesis that Klamelisaurus represented the adult form of Bellusaurus.[3] In 2020, Moore and colleagues listed a number of characteristics (following a 2013 study by Michael Taylor and Mathew Wedel) which identified the type specimen as an adult: the lack of unfused sutures in the vertebral centra; the fusion of the sacrals (hip vertebrae), the fusion of the cervical ribs to their corresponding centra; and the fusion of the scapula and coracoid in the shoulder.[2]

Vertebrae

Zhao stated that the type specimen of Klamelisaurus preserved nine cervicals (neck vertebrae), out of an estimated total of sixteen with a total length of 6.5 metres (21 ft). Moore and colleagues concurred with the number of preserved cervicals, but they noted that the tenth preserved vertebra shows characteristics of both cervicals and dorsals (back vertebae). They estimated a total of fifteen to seventeen cervicals, based on other sauropods with similar patterns of vertebral variation, and indicated that Klamelisaurus had a shorter neck than Omeisaurus tianfuensis, Mamenchisaurus hochuanensis, and M. sinocanadorum. Zhao's original list of distinguishing characteristics (which have been reassessed as being widespread among sauropods) noted that the cervicals were opisthocoelous (with centra convex in front and concave behind); had centra 1.5 to 2 times the length of the dorsal centra; and had tall neural spines, which were bifid (two-pronged) at the back of the neck.[1] In 2004, Paul Upchurch, Paul Barrett, and Peter Dodson suggested that Klamelisaurus can be distinguished by fusion of the last three cervical neural spines,[4] but Moore and colleagues noted that it did not possess this trait. Moore and colleagues noted two unique features (autapomorphies) in the cervicals. First, the spinoprezygapophyseal laminae (SPRLs), ridges of bone extending forward from the neural spines, bore irregular, plate-like extensions. Second, below the SPRLs and in front of depressions called the spinodiapophyseal fossae (SDFs), the sides of the centra bore a set of deep foramina (openings). Although these foramina were present only on the right side of the centra, Moore and colleagues considered them to be unique due to their consistency and the presence of similar structures in other sauropods.[2]

Moore and colleagues identified twelve dorsals and six sacrals in the type specimen of Klamelisaurus. (Zhao previously identified the first sacral of Moore and colleagues as the last dorsal, giving thirteen dorsals and five sacrals.) Although sacral vertebrae are usually identified by contact with the ilium, these bones are not in association in the type specimen. Instead, Moore and colleagues noted a bridge of bone connecting the diapophysis and parapophysis (processes on the side of the vertebra), which was either fused to the now-lost sacral rib (as in other sauropods) or was not associated with a rib at all. Zhao's list of distinguishing characteristics noted that the dorsals were opisthocoelous; the dorsals had shallow pleurocoels (neurovascular openings) and simple lamination (ridging); the dorsal neural spines were low, with the first few being bifid and the last few having expanded tips; the sacral centra were fused such that their boundaries were not visible; and the first four sacral neural spines were fused.[1] Moore and colleagues identified two unique features in the dorsals. First, the sides of some of the dorsals bore sets of three posterior centroparapophyseal laminae (PCPLs). Second, the spinodiapophyseal laminae (SPDLs) on the sides of the neural spines were bifurcated in the middle and rear dorsals, but unlike Bellusaurus the two prongs did not reach the SPRLs or the SPOLs (spinopostzygapophyseal laminae, the rear counterparts of the SPRLs).[2]

Parts of nineteen caudals (tail vertebrae) were found by Moore and colleagues: parts of the first four caudals (labelled as caudals 1–4), five more neural spines from the front of the tail (labelled as caudals 6 and 8–11), and eleven centra from the middle of the tail (labelled as caudals 18–27 and 33). Zhao originally counted two complete caudals, ten neural spines from the front, and ten middle centra, based on which he estimated that sixty were originally present with a total length of 6.55 metres (21.5 ft). Zhao's list of characteristics indicated that the first few caudals were procoelous (with centra concave in front and convex behind), with the rest being amphicoelous (with centra concave on both ends); and the caudal neural spines were claviform (thicker at the tip) and slanted extremely to the rear.[1] Characteristics of the caudals that differentiate Klamelisaurus from Tienshanosaurus include the procoelous front caudals, and the front edge of the tip of the neural spines being slanted to the point of reaching behind the rear edge of the processes known as postzygapophyses.[2]

Limbs and limb girdles

According to Zhao, Klamelisaurus had a thin, elongated scapula and a slender, small coracoid, but Moore and colleagues did not consider his measurements of the scapula to be reliable due to most of the bone being covered by plaster and paint. The acromion process, located at the outer bottom end of the scapula, was broader than in Cetiosaurus, Shunosaurus, and many early-diverging sauropodomorphs, and the top edge of the acromion was straight, not concave like Tienshanosaurus. Zhao observed that the top of the humerus was thick, and slightly curved. Unlike Bellusaurus and many neosauropods, the head of the humerus did not have an overhanging sub-circular process. Moore and colleagues noted a unique characteristic of the humerus: the front surface of the top inner end bore a depression, which was bordered by an S-shaped shelf ending in a rounded bump. Zhao indicated that the ulna was longer than the relatively straight radius, and he suggested that the degree of expansion of the upper ulna was unique; Moore and colleagues found that it was comparable to many other sauropods. The bottom of the front of the radius bore a depression, which Haestasaurus also had but was uncommon among sauropods.[1]

Classification

In 1993 Zhao erected a new subfamily, Klamelisaurinae, of which Klamelisaurus was the only member. He assigned Klamelisaurinae to the obscure sauropod clade Bothrosauropodea.[1] It was considered of uncertain classification by Upchurch et al. (2004), possibly being a non-neosauropod eusauropod.[5]

In their osteological description of Bellusaurus, Moore et al. (2018) refuted the possible synonymy of Klamelisaurus and Bellusaurus by pointing to the slightly older age of the former and non-ontogenetic differences between the two genera.[6]

References

- Zhao, Xijing (1993). "A new Mid-Jurassic sauropod (Klamelisaurus gobiensis gen. et sp. nov.) from Xinjiang, China" (PDF). Vertebrata PalAsiatica. 31 (2): 132–138.

- Moore, A.J.; Upchurch, P.; Barrett, P.M.; Clark, J.M.; Xing, X. (2020). "Osteology of Klamelisaurus gobiensis (Dinosauria, Eusauropoda) and the evolutionary history of Middle–Late Jurassic Chinese sauropods". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology: 1–95. doi:10.1080/14772019.2020.1759706.

- Paul, G.S. (2016). The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs (Second ed.). Princeton University Press. p. 223. ISBN 978-0-691-16766-4.

- Upchurch, P.; Barrett, P.M.; Dodson, P. (2004). "Sauropoda". In Weishampel, D.B.; Dodson, P.; Osmolska, H. (eds.). The Dinosauria (Second ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 299. ISBN 9780520254084.

- P. Upchurch, P. M. Barrett, and P. Dodson. 2004. Sauropoda. In D. B. Weishampel, H. Osmolska, and P. Dodson (eds.), The Dinosauria (2nd edition). University of California Press, Berkeley 259-322

- Moore AJ, Mo J, Clark JM, Xu X. (2018) Cranial anatomy of Bellusaurus sui (Dinosauria: Eusauropoda) from the Middle-Late Jurassic Shishugou Formation of northwest China and a review of sauropod cranial ontogeny. PeerJ 6:e4881 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.4881