Patagotitan

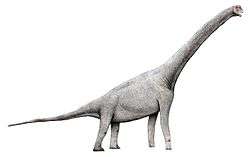

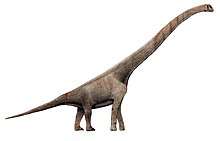

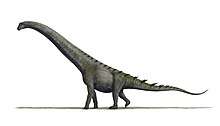

Patagotitan is a genus of titanosaurian sauropod dinosaur from the Cerro Barcino Formation in Chubut Province, Patagonia, Argentina. The genus contains a single species known from multiple individuals: Patagotitan mayorum, first announced in 2014 and then validly named in 2017 by José Carballido, Diego Pol and colleagues. Contemporary studies estimated the length of the type specimen, a young adult, at 37 m (121 ft)[1] with an approximate weight of 69 tonnes (76 tons).[2]

| Patagotitan | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reconstructed skeleton on display at the Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, IL | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Suborder: | †Sauropodomorpha |

| Clade: | †Sauropoda |

| Clade: | †Titanosauria |

| Clade: | †Lithostrotia |

| Clade: | †Lognkosauria |

| Genus: | †Patagotitan Carballido et al., 2017 |

| Type species | |

| †Patagotitan mayorum Carballido et al., 2017 | |

Discovery

Remains of Patagotitan mayorum, a part of a lower thighbone, were initially discovered in 2008 by a farm laborer, Aurelio Hernández, in the desert near La Flecha, about 250 km (160 mi) west of Trelew. Excavation was done by palaeontologists from the Museum of Paleontology Egidio Feruglio. The lead scientists on the excavation were Jose Luis Carballido and Diego Pol, with partial funding from The Jurassic Foundation. Between January 2013 and February 2015, seven paleontological field expeditions were carried out to the La Flecha fossil site, recovering more than 200 fossils, both of sauropods and theropods (represented by 57 teeth). At least six partial skeletons, consisting of approximately 130 bones, were uncovered, making Patagotitan one of the most complete titanosaurs currently known.[2]

The type species Patagotitan mayorum was named and described by José Luis Carballido, Diego Pol, Alejandro Otero, Ignacio Alejandro Cerda, Leonardo Salgado, Alberto Carlos Garrido, Jahandar Ramezani, Néstor Ruben Cúneo and Javier Marcelo Krause in 2017. The generic name combines a reference to Patagonia with a Greek Titan for the "strength and large size" of this titanosaur. The specific name honours the Mayo family, owners of La Flecha ranch.[2]

The holotype, MPEF-PV 3400, was found in a layer of the Cerro Barcino Formation, dating from the latest Albian. The particular stratum has an age of 101.62 plus or minus 0.18 million years ago. The holotype consists of a partial skeleton lacking the skull. It contains three neck vertebrae, six back vertebrae, six front tail vertebrae, three chevrons, ribs, both breast bones, the right scapulocoracoid of the shoulder girdle, both pubic bones and both thighbones. The skeleton was chosen to be the holotype because it was the best preserved and also the one showing the most distinguishing traits. Other specimens were designated as the paratypes. Specimen MPEF-PV 3399 is a second skeleton including six neck vertebrae, four back vertebrae, one front tail vertebra, sixteen rear tail vertebrae, ribs, chevrons, the left lower arm, both ischia, the left pubic bone and the left thighbone. Specimen MPEF-PV 3372 is a tooth. Specimen MPEF-PV 3393 is a rear tail vertebra. Specimen MPEF-PV 3395 is a left humerus as is specimen MPEF-PV 3396, while specimen MPEF-PV 3397 is a right humerus. Specimen MPEF-PV 3375 is a left thighbone while MPEF-PV 3394 is a right one. Specimens MPEF-PV 3391 and MPEF-PV3392 represent two calfbones.[2]

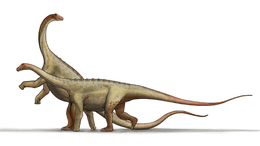

The animals found, though excavated in one quarry, did not all die at the same time. Within the 343 centimetre thick sediment containing the fossils, three distinct but closely spaced horizons correspond to three burial events in which young adults perished due to floods. The water did not transport the carcasses any further but covered them with sandstone and mudstone.[2] The animals were about the same size, differing no more than 5% in length. As far as can be ascertained, all bones discovered belong to the same species and are thus part of a monospecific assemblage.[2]

Description and size

Like other titanosaur sauropods, Patagotitan was a quadrupedal herbivore with a long neck and tail and is notable for its large size. In 2014 news reports stated size estimates of 40 m (131 ft) long with a weight of 77 tonnes (85 tons);[3][1] science writer Riley Black had cautioned in 2014 that it was still too early to make size estimates with the desirable scientific certainty.[4] In 2017 the species description of Patagotitan mayorum was published which estimated a length of 37 m (121 ft) long, with an approximate weight of 69 tonnes (76 tons) when using a scaling equation, and 44.2–77.6 tonnes (43.5–76.4 long tons; 48.7–85.5 short tons) when using volumetric method based on 3D skeletal models.[1][2] In 2019 Gregory S. Paul listed Patagotitan at 31 m (102 ft) in length and 50–55 tonnes (49–54 long tons; 55–61 short tons) in weight using volumetric models, making it smaller than Argentinosaurus which was estimated at 35 m (115 ft) or more in length and 65–75 tonnes (64–74 long tons; 72–83 short tons) in weight.[5]

Patagotitan's humerus was 1.675 m (5.50 ft) long, smaller from that of other giants such as Notocolossus (1.76 meters) and Paralititan (1.69 meters). It's femur measured 2.38 m (7.8 ft) in length making it the longest known, although Paul estimated the total size of the isolated femur (MLP-DP 46-VIII-21-3 specimen) ,which is referred to Argentinosaurus, at 2.575 m (8.45 ft) making it larger than Patagotitan's. He also noticed that the articulated dorsal series length was larger in Argentinosaurus (4.47 meters) than in Patagotitan (3.67 meters).[5]

The researchers who described Patagotitan stated in the media:[6]

Given the size of these bones, which surpass any of the previously known giant animals, the new dinosaur is the largest animal known that walked on Earth.

Following the publication of Patagotitan, Riley Black and paleontologist Matt Wedel further cautioned against the media hype. In blog posts, Wedel noted that based on available measurements Patagotitan was comparable in size to other known giant titanosaurs, however, almost every bone measurement that could be compared are larger in Argentinosaurus. Wedel also criticised the researchers mass estimation technique. [7][8][9] In other studies Argentinosaurus has been estimated at 65–96.4 tonnes (71.7–106.3 tons).[10][11][12][5]

Distinguishing traits

The authors indicated nine distinguishing traits of Patagotitan. The first three back vertebra have a lamina prezygodiapophysealis, a ridge running between the front articular process and the side process, that is vertical because the front articular process is situated considerably higher than the side process. With the first two back vertebrae, the ridge running to below from the side front of the neural spine has a bulge at the underside. Secondary articulating processes of the hyposphene-hypantrum complex type are limited to the articulation between the third and fourth back vertebra. The middle and rear back vertebrae have vertical neural spines. In the first tail vertebra, the centrum or main vertebral body has a flat articulation facet in front and a convex facet at the rear. The front tail vertebrae have neural spines of which the transverse width is four to six times larger than their length measured from the front to the rear. The front tail vertebrae have neural spines that show some bifurcation. The upper arm bone has a distinct bulge on the rear outer side. The lower thighbone has a straight edge on the outer side.[2]

Classification

In 2017, Patagotitan was placed, within the Titanosauria, in the Eutitanosauria and more precisely the Lognkosauria, as a sister species of Argentinosaurus. Several subclades of the Titanosauria would have independently acquired a large body mass. One such event would have taken place at the base of the Notocolossus + Lognkosauria clade leading to a tripling of weight from maximal twenty to maximal sixty tonnes.[2]

| Eutitanosauria |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleoecology

Patagotitan lived during the Late Cretaceous period, between 102 and 95 million years ago, in what was then a forested region.[3][13][14] The bearing sediments indicate that sedimentation took place with a low energy setting, related to floodplains of a meandering system (Carmona et al., 2016).[2]

See also

Further reading

References

- Giant dinosaur slims down a bit. BBC News Science & Environment

- Carballido, J.L.; Pol, D.; Otero, A.; Cerda, I.A.; Salgado, L.; Garrido, A.C.; Ramezani, J.; Cúneo, N.R.; Krause, J.M. (2017). "A new giant titanosaur sheds light on body mass evolution among sauropod dinosaurs". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 284 (1860): 20171219. doi:10.1098/rspb.2017.1219. PMC 5563814. PMID 28794222.

- Morgan, James (17 May 2014). "BBC News - 'Biggest dinosaur ever' discovered". BBC News. Bbc.com. Retrieved 17 May 2014.

- Yong, Ed (18 May 2014). "Biggest Dinosaur Ever? Maybe. Maybe Not. – Phenomena". BMC Biology. 10: 60. doi:10.1186/1741-7007-10-60. PMC 3403949. PMID 22781121. Retrieved 11 June 2016.

- Paul, Gregory S. (2019). "Determining the largest known land animal: A critical comparison of differing methods for restoring the volume and mass of extinct animals" (PDF). Annals of the Carnegie Museum. 85 (4): 335–358.

- Morgan, James (17 May 2014). "'Biggest dinosaur ever' discovered". BBC News. Retrieved 8 January 2019.

- Switek, Brian. "Did Scientists Just Unveil the Biggest Dinosaur of All Time?". Smithsonian. Retrieved 8 January 2019.

- "Don't believe the hype: Patagotitan was not bigger than Argentinosaurus". Sauropod Vertebra Picture of the Week. 9 August 2017. Retrieved 8 January 2019.

- "Some further thoughts on Patagotitan". Sauropod Vertebra Picture of the Week. 10 August 2017. Retrieved 8 January 2019.

- Mazzetta, G.V.; Christiansen, P.; Farina, R.A. (2004). "Giants and bizarres: body size of some southern South American Cretaceous dinosaurs" (PDF). Historical Biology. 2004 (2–4): 1–13. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.694.1650. doi:10.1080/08912960410001715132.

- Sellers, W. I.; Margetts, L.; Coria, R. A. B.; Manning, P. L. (2013). Carrier, David (ed.). "March of the Titans: The Locomotor Capabilities of Sauropod Dinosaurs". PLoS ONE. 8 (10): e78733. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...878733S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0078733. PMC 3864407. PMID 24348896.

- González Riga, Bernardo J.; Lamanna, Matthew C.; Ortiz David, Leonardo D.; Calvo, Jorge O.; Coria, Juan P. (2016). "A gigantic new dinosaur from Argentina and the evolution of the sauropod hind foot". Scientific Reports. 6: 19165. Bibcode:2016NatSR...619165G. doi:10.1038/srep19165. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 4725985. PMID 26777391.

- Gillian Mohney via Good Morning America (17 May 2014). "Researchers Discover Fossils of Largest Dino Believed to Ever Walk the Earth - ABC News". Abcnews.go.com. Retrieved 17 May 2014.

- "Argentine fossil biggest dinosaur ever: scientists". NY Daily News. Retrieved 17 May 2014.