Shiva Sutras

The Shiva Sutras (IAST: Śivasūtrāṇi) or Māheśvara Sūtrāṇi are fourteen verses that organize the phonemes of Sanskrit as referred to in the Aṣṭādhyāyī of Pāṇini, the foundational text of Sanskrit grammar.

Within the tradition they are known as the Akṣarasamāmnāya, "recitation of phonemes," but they are popularly known as the Shiva Sutras because they are said to have been revealed to Pāṇini by Shiva. They were either composed by Pāṇini to accompany his Aṣṭādhyāyī or predate him. The latter is less plausible, but the practice of encoding complex rules in short, mnemonic verses is typical of the sutra style.

Text

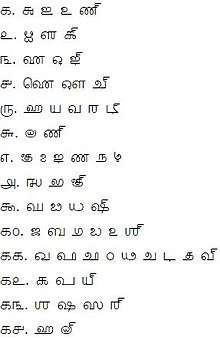

| IAST | देवनागरी (Devanāgari) | తెలుగు (Telugu) | ಕನ್ನಡ (Kannada) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1. a i u Ṇ |

१. अ इ उ ण्। |

1. అ ఇ ఉ ణ్ |

1. అ ఇ ಉ ಣ್ |

Each of the fourteen verses consists of a group of basic Sanskrit phonemes (i.e. either open syllables consisting either of initial vowels or consonants followed by the basic vowel "a") followed by a single 'dummy letter', or anubandha, conventionally rendered by capital letters in Roman transliteration and named 'IT' by Pāṇini.

This allows Pāṇini to refer to groups of phonemes with pratyāhāras, which consist of a phoneme-letter and an anubandha (and often the vowel a to aid pronunciation) and signify all of the intervening phonemes. Pratyāhāras are thus single syllables, but they can be declined (see Aṣṭādhyāyī 6.1.77 below). Hence the pratyāhāra aL refers to all phonemes (because it consists of the first phoneme of the first verse (a) and the last anubandha of the last verse (L); aC refers to vowels (i.e., all of the phonemes before the anubandha C: i.e. a i u ṛ ḷ e o ai au); haL to consonants, and so on.

Note that some pratyāhāras are ambiguous. The anubandha Ṇ occurs twice in the list, which means that you can assign two different meanings to pratyāhāra aṆ (including or excluding ṛ, etc.); in fact, both of these meanings are used in the Aṣṭādhyāyī. On the other hand, the pratyāhāra haL is always used in the meaning "all consonants"—Pāṇini never uses pratyāhāras to refer to sets consisting of a single phoneme.

From these 14 verses, a total of 281 pratyāhāras can be formed: 14*3 + 13*2 + 12*2 + 11*2 + 10*4 + 9*1 + 8*5 + 7*2 + 6*3 * 5*5 + 4*8 + 3*2 + 2*3 +1*1, minus 14 (as Pāṇini does not use single element pratyāhāras) minus 10 (as there are 10 duplicate sets due to h appearing twice); the second multiplier in each term represents the number of phonemes in each. But Pāṇini uses only 41 (with a 42nd introduced by later grammarians, raṆ=r l) pratyāhāras in the Aṣṭādhyāyī.

The Shiva Sutras put phonemes with a similar manner of articulation together (so sibilants in 13 śa ṣa sa R, nasals in 7 ñ m ṅ ṇ n M). Economy (Sanskrit: lāghava) is a major principle of their organization, and it is debated whether Pāṇini deliberately encoded phonological patterns in them (as they were treated in traditional phonetic texts called Prātiśakyas) or simply grouped together phonemes which he needed to refer to in the Aṣṭādhyāyī and which only secondarily reflect phonological patterns (as argued by Paul Kiparsky and Wiebke Petersen, for example). Pāṇini does not use the Shiva Sutras to refer to homorganic stops (stop consonants produced at the same place of articulation), but rather the anubandha U: to refer to the palatals c ch j jh he uses cU.

As an example, consider Aṣṭādhyāyī 6.1.77: इकः यण् अचि iKaḥ yaṆ aCi:

- iK means i u ṛ ḷ,

- iKaḥ is iK in the genitive case, so it means ' in place of i u ṛ ḷ;

- yaṆ means the semivowels y v r l and is in the nominative, so iKaḥ yaṆ means: y v r l replace i u ṛ ḷ.

- aC means all vowels, as noted above

- aCi is in the locative case, so it means before any vowel.

Hence this rule replaces a vowel with its corresponding semivowel when followed by any vowel, and that is why dadhi together with atra makes dadhyatra. To apply this rule correctly we must be aware of some of the other rules of the grammar, such as:

- 1.1.49 षष्ठी स्थानेयोगा ṣaṣṭhī sthāneyogā which says that the genitive case in a sutra signifies "in the place of"

- 1.1.50 स्थानेऽन्तरतमः sthāne 'ntaratamaḥ which says that in a substitution, the element in the substitute series that most closely resembles the letter to be substituted should be used (e.g. y for i, r for ṛ etc.)

- 1.1.71 आदिरन्त्येन सहेता ādir antyena sahetā which says that a sequence with an element at the beginning (e.g. i) and an IT letter (e.g. K) at the end stands for the intervening letters (i.e. i u ṛ ḷ, because the Shiva sutras read i u ṛ ḷ K).

Also, rules can be debarred by other rules:

- 6.1.101 अकः सवर्णे दीर्घः aKaḥ savarṇe dīrghaḥ teaches that vowels (from the aK pratyāhāra) of the same quality come together to make a long vowel, so for instance dadhi and indraḥ make dadhīndraḥ, not *dadhyindraḥ. This aKaḥ savarṇe dīrghaḥ rule takes precedence over the general iKaḥ yaṆ aCi rule mentioned above, because this rule is more specific.

See also

- Other languages

- Alphabet song

- Iroha, a Japanese poem with similar function

- Thousand Character Classic, Chinese poem with similar function, esp. used in Korea

External links

- Paper by Paul Kiparsky on 'Economy and the Construction of the Śiva sūtras'.

- Paper by Andras Kornai relating the Śiva sūtras to contemporary Feature Geometry.

- Paper by Wiebke Petersen on 'A Mathematical Analysis of Pāṇini’s Śiva sūtras.'

- Paper by Madhav Deshpande on 'Who Inspired Pāṇini? Reconstructing the Hindu and Buddhist Counter-Claims.'