Canaan

Canaan (/ˈkeɪnən/; Northwest Semitic: knaʿn; Phoenician: 𐤊𐤍𐤏𐤍 – Kenāʿan; Hebrew: כְּנַעַן – Kənáʿan, in pausa כְּנָעַן – Kənā́ʿan; Biblical Greek: Χανααν – Khanaan[1]; Arabic: كَنْعَانُ – Kan‘ān) was a Semitic-speaking civilization and region in the Ancient Near East during the late 2nd millennium BC. The name Canaan appears throughout the Bible, where it corresponds to the Levant, in particular to the areas of the Southern Levant that provide the main setting of the narrative of the Bible: Phoenicia, Philistia, Israel, and other nations.

region | |

The major Canaanite city-states in the Bronze Age | |

| Polities and peoples | |

| Canaanite languages | |

.jpg)

The word Canaanites serves as an ethnic catch-all term covering various indigenous populations—both settled and nomadic-pastoral groups—throughout the regions of the southern Levant or Canaan.[2] It is by far the most frequently used ethnic term in the Bible.[3] In the Book of Joshua, Canaanites are included in a list of nations to exterminate,[4] and later described as a group which the Israelites had annihilated.[5] Biblical scholar Mark Smith notes that archaeological data suggests "that the Israelite culture largely overlapped with and derived from Canaanite culture... In short, Israelite culture was largely Canaanite in nature."[6]:13–14[7][8] The name "Canaanites" is attested, many centuries later, as the endonym of the people later known to the Ancient Greeks from c. 500 BC as Phoenicians,[5] and after the emigration of Canaanite-speakers to Carthage (founded in the 9th century BC), was also used as a self-designation by the Punics (chanani) of North Africa during Late Antiquity.

Canaan had significant geopolitical importance in the Late Bronze Age Amarna period (14th century BC) as the area where the spheres of interest of the Egyptian, Hittite, Mitanni and Assyrian Empires converged. Much of modern knowledge about Canaan stems from archaeological excavation in this area at sites such as Tel Hazor, Tel Megiddo, En Esur, and Gezer.

Etymology

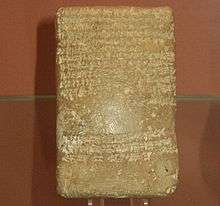

The English term Canaan (pronounced /ˈkeɪnən/ since c. 1500, due to the Great Vowel Shift) comes from the Hebrew כנען (knʿn), via Greek Χανααν Khanaan and Latin Canaan. It appears as 𒆳𒆠𒈾𒄴𒈾 (KURki-na-aḫ-na) in the Amarna letters (14th century BC), and knʿn is found on coins from Phoenicia in the last half of the 1st millennium. It first occurs in Greek in the writings of Hecataeus as Khna (Χνᾶ).[9]

The etymology is uncertain. An early explanation derives the term from the Semitic root knʿ "to be low, humble, subjugated".[10] Some scholars have suggested that this implies an original meaning of "lowlands", in contrast with Aram, which would then mean "highlands",[11] whereas others have suggested it meant "the subjugated" as the name of Egypt's province in the Levant, and evolved into the proper name in a similar fashion to Provincia Nostra (the first Roman colony north of the Alps, which became Provence).[12]

An alternative suggestion put forward by Ephraim Avigdor Speiser in 1936 derives the term from Hurrian Kinahhu, purportedly referring to the colour purple, so that Canaan and Phoenicia would be synonyms ("Land of Purple"). Tablets found in the Hurrian city of Nuzi in the early 20th century appear to use the term Kinahnu as a synonym for red or purple dye, laboriously produced by the Kassite rulers of Babylon from murex molluscs as early as 1600 BC, and on the Mediterranean coast by the Phoenicians from a byproduct of glassmaking. Purple cloth became a renowned Canaanite export commodity which is mentioned in Exodus. The dyes may have been named after their place of origin. The name 'Phoenicia' is connected with the Greek word for "purple", apparently referring to the same product, but it is difficult to state with certainty whether the Greek word came from the name, or vice versa. The purple cloth of Tyre in Phoenicia was well known far and wide and was associated by the Romans with nobility and royalty. However, according to Robert Drews, Speiser's proposal has generally been abandoned.[13][14]

History

Overview

- Prior to 4500 BC (prehistory – Stone Age: hunter-gatherer societies slowly giving way to farming and herding societies;

- 4500-3500 BC (Chalcolithic): early metal-working and farming;

- 3500–2000 BC (Early Bronze): prior to written records in the area;

- 2000–1550 BC (Middle Bronze): city-states;

- 1550–1200 BC (Late Bronze): Egyptian hegemony;

After the Iron Age the periods are named after the various empires that ruled the region: Assyrian, Babylonian, Persian, Greek (Hellenistic) and Roman.[15]

Prehistory

Canaanite culture apparently developed in situ from the earlier chalcolithic Proto-Canaanites[16] called the Ghassulian archeological culture. Ghassulian culture itself developed from the Circum-Arabian Nomadic Pastoral Complex, which in turn developed from a fusion of their ancestral Natufian and Harifian cultures with Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB) farming cultures, practicing animal domestication, during the 6200 BC climatic crisis which led to the Agricultural Revolution/Neolithic Revolution in the Levant.[17]

Chalcolithic (4500-3500)

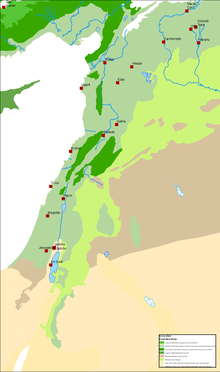

The Proto-Canaanites migrated into the Levant starting in 4500 BC. They pioneered the Mediterranean agricultural system typical of the Canaanite region, which comprised intensive subsistence horticulture, extensive grain growing, commercial wine and olive cultivation and transhumance pastoralism. They lived in small villages, mining and manufacturing copper. The Proto-Canaanites became Canaanites circa 3800 BC when the Semetic language split off from Afroasiatic language. The two principal temples of the Proto-Canaanites were built at Ein Gedi and Meggido. The majority of Canaan is covered by the Eastern Mediterranean conifer-sclerophyllous-broadleaf forests ecoregion.

Early Bronze Age (3200–2000)

By the Early Bronze Age other sites had developed, such as Ebla (where an East Semitic language, Eblaite, was spoken), which by c. 2300 BC was incorporated into the Mesopotamia-based Akkadian Empire of Sargon the Great and Naram-Sin of Akkad (biblical Accad). Sumerian references to the Mar.tu ("tent dwellers", later Amurru, i.e. Amorite) country West of the Euphrates date from even earlier than Sargon, at least to the reign of the Sumerian king, Enshakushanna of Uruk, and one tablet credits the early Sumerian king Lugal-anne-mundu with holding sway in the region, although this tablet is considered less credible because it was produced centuries later.

The archives of Ebla show reference to a number of biblical sites, including Hazor, Jerusalem, and as a number of people have claimed, to Sodom and Gomorrah mentioned in Genesis as well. Ebla and Amorites at Hazor, Kadesh (Qadesh-on-the-Orontes), and elsewhere in Amurru (Syria) bordered Canaan in the north and northeast. (Ugarit may be included among these Amoritic entities.[18]) The collapse of the Akkadian Empire in 2154 BC saw the arrival of peoples using Khirbet Kerak Ware pottery,[19] coming originally from the Zagros Mountains (in modern Iran) east of the Tigris. In addition, DNA analysis revealed that between 2500–1000 BC, populations from the Chalcolithic Zagros and Bronze Age Caucasus migrated to the Southern Levant.[20]

The first cities in the southern Levant arose during this period.[21] The major sites were En Esur and Meggido These "proto-Canaanites" were in regular contact with the other peoples to their south such as Egypt, and to the north Asia Minor (Hurrians, Hattians, Hittites, Luwians) and Mesopotamia (Sumer, Akkad, Assyria), a trend that continued through the Iron Age.[21] The end of the period is marked by the abandonment of the cities and a return to lifestyles based on farming villages and semi-nomadic herding, although specialised craft production continued and trade routes remained open.[21] Archaeologically, The Late Bronze Age state of Ugarit (at Ras Shamra in Syria) is considered quintessentially Canaanite,[6] even though its Ugaritic language does not belong to the Canaanite language group proper.[22][23][24]

Middle Bronze Age (2000–1550)

Urbanism returned and the region was divided among small city-states, the most important of which seems to have been Hazor.[25] Many aspects of Canaanite material culture now reflected a Mesopotamian influence, and the entire region became more tightly integrated into a vast international trading network.[25]

As early as Naram-Sin of Akkad's reign (c. 2240 BC), Amurru was called one of the "four quarters" surrounding Akkad, along with Subartu/Assyria, Sumer, and Elam.

Amorite dynasties also came to dominate in much of Mesopotamia, including in Larsa, Isin and founding the state of Babylon in 1894 BC. Later on, Amurru became the Assyrian/Akkadian term for the interior of south as well as for northerly Canaan. At this time the Canaanite area seemed divided between two confederacies, one centred upon Megiddo in the Jezreel Valley, the second on the more northerly city of Kadesh on the Orontes River.

An Amorite chieftain named Sumu-abum founded Babylon as an independent city-state in 1894 BC. One Amorite king of Babylonia, Hammurabi (1792–1750 BC) founded the first Babylonian Empire, which lasted only as long as his lifetime. Upon his death, the Amorites were driven from Assyria, but remained masters of Babylonia until 1595 BC, when they were ejected by the Hittites.

The semi-fictional Story of Sinuhe describes an Egyptian officer, Sinuhe, conducting military activities in the area of "Upper Retchenu" and "Finqu" during the reign of Senusret I (c. 1950 BC). The earliest bonafide Egyptian report of a campaign to "Mentu", "Retchenu" and "Sekmem" (Shechem) is the Sebek-khu Stele, dated to the reign of Senusret III (c. 1862 BC).

Around 1650 BC, Canaanites invaded the eastern Delta of Egypt, where, known as the Hyksos, they became the dominant power.[30] In Egyptian inscriptions, Amar and Amurru (Amorites) are applied strictly to the more northerly mountain region east of Phoenicia, extending to the Orontes.

Archaeological excavations of a number of sites, later identified as Canaanite, show that prosperity of the region reached its apogee during this Middle Bronze Age period, under leadership of the city of Hazor, at least nominally tributary to Egypt for much of the period. In the north, the cities of Yamkhad and Qatna were hegemons of important confederacies, and it would appear that biblical Hazor was the chief city of another important coalition in the south.

Late Bronze Age (1550–1200)

In the early Late Bronze Age, Canaanite confederacies centered on Megiddo and Kadesh, before again being brought into the Egyptian Empire and Hittite Empire. Later still, the Neo-Assyrian Empire assimilated the region.

According to the Bible, the migrant ancient Semitic-speaking peoples who appear to have settled in the region included (among others) the Amorites, who had earlier controlled Babylonia. The Hebrew Bible mentions the Amorites in the Table of Peoples (Book of Genesis 10:16–18a). Evidently, the Amorites played a significant role in the early history of Canaan. In Book of Genesis 14:7 f., Book of Joshua 10:5 f., Book of Deuteronomy 1:19 f., 27, 44, we find them located in the southern mountain country, while verses such as Book of Numbers 21:13, Book of Joshua 9:10, 24:8, 12, etc.tell of two great Amorite kings residing at Heshbon and Ashteroth, east of the Jordan. However, other passages such as Book of Genesis 15:16, 48:22, Book of Joshua 24:15, Book of Judges 1:34, etc. regard the name Amorite as synonymous with "Canaanite"; however "Amorite" is never used for the population on the coast.

In the centuries preceding the appearance of the biblical Hebrews, parts of Canaan and southwestern Syria became tributary to the Egyptian Pharaohs, although domination by the Egyptians remained sporadic, and not strong enough to prevent frequent local rebellions and inter-city struggles. Other areas such as northern Canaan and northern Syria came to be ruled by the Assyrians during this period.

Under Thutmose III (1479–1426 BC) and Amenhotep II (1427–1400 BC), the regular presence of the strong hand of the Egyptian ruler and his armies kept the Amorites and Canaanites sufficiently loyal. Nevertheless, Thutmose III reported a new and troubling element in the population. Habiru or (in Egyptian) 'Apiru, are reported for the first time. These seem to have been mercenaries, brigands, or outlaws, who may have at one time led a settled life, but with bad luck or due to the force of circumstances, contributed a rootless element to the population, prepared to hire themselves to whichever local mayor, king, or princeling would pay for their support.

Although Habiru SA-GAZ (a Sumerian ideogram glossed as "brigand" in Akkadian), and sometimes Habiri (an Akkadian word) had been reported in Mesopotamia from the reign of the Sumerian king, Shulgi of Ur III, their appearance in Canaan appears to have been due to the arrival of a new state based in Asia Minor to the north of Assyria and based upon a Maryannu aristocracy of horse-drawn charioteers, associated with the Indo-Aryan rulers of the Hurrians, known as Mitanni.

The Habiru seem to have been more a social class than an ethnic group. One analysis shows that the majority were, however, Hurrian (a non-Semitic-speaking group from Asia Minor who spoke a language isolate), though there were a number of Semites and even some Kassite and Luwian adventurers amongst their number. The reign of Amenhotep III, as a result was not quite so tranquil for the Asiatic province, as Habiru/'Apiru contributed to greater political instability. It is believed that turbulent chiefs began to seek their opportunities, though as a rule they could not find them without the help of a neighbouring king. The boldest of the disaffected nobles was Aziru, son of Abdi-Ashirta, a prince of Amurru, who, even before the death of Amenhotep III, endeavoured to extend his power into the plain of Damascus. Akizzi, governor of Katna (Qatna?) (near Hamath), reported this to the Pharaoh, who seems to have sought to frustrate Aziru's attempts. In the reign of the next pharaoh (Akhenaten, reigned c. 1352 to c. 1335 BC) however, both father and son caused infinite trouble to loyal servants of Egypt like Rib-Hadda, governor of Gubla (Gebal), not the least through transferring loyalty from the Egyptian crown to that of the expanding neighbouring Asia-Minor-based Hittite Empire under Suppiluliuma I[31] (reigned c. 1344–1322 BC)

Egyptian power in Canaan thus suffered a major setback when the Hittites (or Hat.ti) advanced into Syria in the reign of Amenhotep III, and when they became even more threatening in that of his successor, displacing the Amorites and prompting a resumption of Semitic migration. Abdi-Ashirta and his son Aziru, at first afraid of the Hittites, afterwards made a treaty with their king, and joining with the Hittites, attacked and conquered the districts remaining loyal to Egypt. In vain did Rib-Hadda send touching appeals for aid to the distant Pharaoh, who was far too engaged in his religious innovations to attend to such messages.

The Amarna letters tell of the Habiri in northern Syria. Etakkama wrote thus to the Pharaoh:

- "Behold, Namyawaza has surrendered all the cities of the king, my lord to the SA-GAZ in the land of Kadesh and in Ubi. But I will go, and if thy gods and thy sun go before me, I will bring back the cities to the king, my lord, from the Habiri, to show myself subject to him; and I will expel the SA-GAZ."

Similarly, Zimrida, king of Sidon (named 'Siduna'), declared, "All my cities which the king has given into my hand, have come into the hand of the Habiri." The king of Jerusalem, Abdi-Heba, reported to the Pharaoh:

- "If (Egyptian) troops come this year, lands and princes will remain to the king, my lord; but if troops come not, these lands and princes will not remain to the king, my lord."

Abdi-heba's principal trouble arose from persons called Iilkili and the sons of Labaya, who are said to have entered into a treasonable league with the Habiri. Apparently this restless warrior found his death at the siege of Gina. All these princes, however, maligned each other in their letters to the Pharaoh, and protested their own innocence of traitorous intentions. Namyawaza, for instance, whom Etakkama (see above) accused of disloyalty, wrote thus to the Pharaoh,

- "Behold, I and my warriors and my chariots, together with my brethren and my SA-GAZ, and my Suti ?9 are at the disposal of the (royal) troops to go whithersoever the king, my lord, commands."[32]

From the mid 14th century BC through to the 11th century BC, much of Canaan (particularly the north, central, and eastern regions of Syria and the northwestern Mediterranean coastal regions) fell to the Middle Assyrian Empire, and both Egyptian and Hittite influence waned as a result. Powerful Assyrian kings extracted tribute from Canaanite states and cities from north, east, and central Syria as far as the Mediterranean.[33] The King of Assyria Arik-den-ili (reigned c. 1307–1296 BC), consolidated Assyrian power in the Levant, he defeated and conquered ancient Semitic-speaking peoples of the so-called Ahlamu group. He was followed by Adad-nirari I (1295–1275 BC) who continued expansion to the northwest, mainly at the expense of the Hittites and Hurrians, conquering Hittite territories such as Carchemish and beyond. In 1274 BC Shalmaneser I ascended the Assyrian throne. A powerful warrior king, he annexed territories in Syria and Canaan previously under Egyptian or Hittite influence, and the growing power of Assyria was perhaps the reason why these two states made peace with one another.[33] This trend continued under Tukulti-Ninurta I (1244–1208 BC) and after a hiatus, under Tiglath-Pileser I (1115–1077 BC) who conquered the Arameans of northern Syria, and thence he proceeded to conquer Damascus and the Canaanite/Phoenician cities of (Byblos), Sidon, Tyre and finally Arvad.[33]

Bronze Age collapse

Ann Killebrew has shown that cities such as Jerusalem were large and important walled settlements in the 'Pre-Israelite' Middle Bronze IIB and the Israelite Iron Age IIC period (c. 1800–1550 and 720–586 BC), but that during the intervening Late Bronze (LB) and Iron Age I and IIA/B Ages sites like Jerusalem were small and relatively insignificant and unfortified towns.[34]

Just after the Amarna period, a new problem arose which was to trouble the Egyptian control of southern Canaan (the rest of the region now being under Assyrian control). Pharaoh Horemhab campaigned against Shasu (Egyptian = "wanderers") living in nomadic pastoralist tribes, who had moved across the Jordan River to threaten Egyptian trade through Galilee and Jezreel. Seti I (c. 1290 BC) is said to have conquered these Shasu, Semitic-speaking nomads living just south and east of the Dead Sea, from the fortress of Taru (Shtir?) to "Ka-n-'-na". After the near collapse of the Battle of Kadesh, Rameses II had to campaign vigorously in Canaan to maintain Egyptian power. Egyptian forces penetrated into Moab and Ammon, where a permanent fortress garrison (called simply "Rameses") was established.

Some believe the "Habiru" signified generally all the nomadic tribes known as "Hebrews", and particularly the early Israelites of the period of the "judges", who sought to appropriate the fertile region for themselves.[35] However, the term was rarely used to describe the Shasu. Whether the term may also include other related ancient Semitic-speaking peoples such as the Moabites, Ammonites and Edomites is uncertain. It may not be an ethnonym at all; see the article Habiru for details.

Iron Age

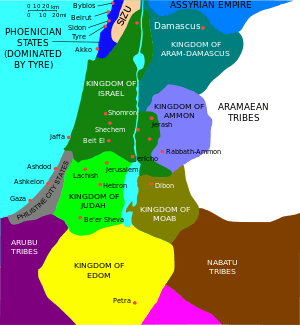

By the Early Iron Age, the southern Levant came to be dominated by the kingdoms of Israel and Judah, besides the Philistine city-states on the Mediterranean coast, and the kingdoms of Moab, Ammon, and Aram-Damascus east of the Jordan River, and Edom to the south. The northern Levant was divided into various petty kingdoms, the so-called Syro-Hittite states and the Phoenician city-states.

The entire region (including all Phoenician/Canaanite and Aramean states, together with Israel, Philistia, and Samarra) was conquered by the Neo-Assyrian Empire during the 10th and 9th centuries BC, and would remain so for three hundred years until the end of the 7th century BC. Assyrian emperor-kings such as Ashurnasirpal, Adad-nirari II, Sargon II, Tiglath-Pileser III, Esarhaddon, Sennacherib and Ashurbanipal came to dominate Canaanite affairs. The Egyptians, then under a Nubian Dynasty, made a failed attempt to regain a foothold in the region, but were vanquished by the Assyrians, leading to an Assyrian invasion and conquest of Egypt and the destruction of the Kushite Empire. The Kingdom of Judah was forced to pay tribute to Assyria. Between 616 and 605 BC the Assyrian Empire collapsed due to a series of bitter civil wars, followed by an attack by an alliance of Babylonians, Medes, and Persians and the Scythians. The Babylonians inherited the western part of the empire of their Assyrian brethren, including all the lands in Canaan and Syria, together with Israel and Judah. They successfully defeated the Egyptians, who had belatedly attempted to aid their former masters, the Assyrians, and then remained in the region in an attempt to regain a foothold in the Near East. The Babylonian Empire itself collapsed in 539 BC, and Canaan fell to the Persians and became a part of the Achaemenid Empire. It remained so until in 332 BC it was conquered by the Greeks under Alexander the Great, later to fall to Rome in the late 2nd century BC, and then Byzantium, until the Arab Islamic invasion and conquest of the 7th century.[33]

Culture

Canaan included what today are Lebanon, Israel, northwestern Jordan, and some western areas of Syria.[6]:13 According to archaeologist Jonathan N. Tubb, "Ammonites, Moabites, Israelites, and Phoenicians undoubtedly achieved their own cultural identities, and yet ethnically they were all Canaanites", "the same people who settled in farming villages in the region in the 8th millennium BC."[6]:13–14

There is uncertainty about whether the name Canaan refers to a specific Semitic-speaking ethnic group wherever they live, the homeland of this ethnic group, a region under the control of this ethnic group, or perhaps any combination of the three.

Canaanite civilization was a response to long periods of stable climate interrupted by short periods of climate change. During these periods, Canaanites profited from their intermediary position between the ancient civilizations of the Middle East—Ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia (Sumer, Akkad, Assyria, Babylonia), the Hittites, and Minoan Crete—to become city states of merchant princes along the coast, with small kingdoms specializing in agricultural products in the interior. This polarity, between coastal towns and agrarian hinterland, was illustrated in Canaanite mythology by the struggle between the storm god, variously called Teshub (Hurrian) or Ba'al Hadad (Semitic Amorite/Aramean) and Ya'a, Yaw, Yahu, or Yam, god of the sea and rivers. Early Canaanite civilization was characterized by small walled market towns, surrounded by peasant farmers growing a range of local horticultural products, along with commercial growing of olives, grapes for wine, and pistachios, surrounded by extensive grain cropping, predominantly wheat and barley. Harvest in early summer was a season when transhumance nomadism was practiced—shepherds staying with their flocks during the wet season and returning to graze them on the harvested stubble, closer to water supplies in the summer. Evidence of this cycle of agriculture is found in the Gezer calendar and in the biblical cycle of the year.

Periods of rapid climate change generally saw a collapse of this mixed Mediterranean farming system; commercial production was replaced with subsistence agricultural foodstuffs; and transhumance pastoralism became a year-round nomadic pastoral activity, whilst tribal groups wandered in a circular pattern north to the Euphrates, or south to the Egyptian delta with their flocks. Occasionally, tribal chieftains would emerge, raiding enemy settlements and rewarding loyal followers from the spoils or by tariffs levied on merchants. Should the cities band together and retaliate, a neighbouring state intervene or should the chieftain suffer a reversal of fortune, allies would fall away or intertribal feuding would return. It has been suggested that the Patriarchal tales of the Bible reflect such social forms.[36] During the periods of the collapse of Akkadian Empire in Mesopotamia and the First Intermediate Period of Egypt, the Hyksos invasions and the end of the Middle Bronze Age in Assyria and Babylonia, and the Late Bronze Age collapse, trade through the Canaanite area would dwindle, as Egypt, Babylonia, and to a lesser degree Assyria, withdrew into their isolation. When the climates stabilized, trade would resume firstly along the coast in the area of the Philistine and Phoenician cities. As markets redeveloped, new trade routes that would avoid the heavy tariffs of the coast would develop from Kadesh Barnea, through Hebron, Lachish, Jerusalem, Bethel, Samaria, Shechem, Shiloh through Galilee to Jezreel, Hazor, and Megiddo. Secondary Canaanite cities would develop in this region. Further economic development would see the creation of a third trade route from Eilath, Timna, Edom (Seir), Moab, Ammon, and thence to the Aramean states of Damascus and Palmyra. Earlier states (for example the Philistines and Tyrians in the case of Judah and Samaria, for the second route, and Judah and Israel for the third route) tried generally unsuccessfully to control the interior trade.[37]

Eventually, the prosperity of this trade would attract more powerful regional neighbours, such as Ancient Egypt, Assyria, the Babylonians, Persians, Ancient Greeks, and Romans, who would control the Canaanites politically, levying tribute, taxes, and tariffs. Often in such periods, thorough overgrazing would result in a climatic collapse and a repeat of the cycle (e.g., PPNB, Ghassulian, Uruk, and the Bronze Age cycles already mentioned). The fall of later Canaanite civilization occurred with the incorporation of the area into the Greco-Roman world (as Iudaea province), and after Byzantine times, into the Muslim Arab and proto-Muslim Umayyad Caliphate. Western Aramaic, one of the two lingua francas of Canaanite civilization, is still spoken in a number of small Syrian villages, whilst Phoenician Canaanite disappeared as a spoken language in about 100 AD. A separate Akkadian-infused Eastern Aramaic is still spoken by the existing Assyrians of Iraq, Iran, northeast Syria, and southeast Turkey.

Tel Kabri contains the remains of a Canaanite city from the Middle Bronze Age (2000–1550 BC). The city, the most important of the cities in the Western Galilee during that period, had a palace at its center. Tel Kabri is the only Canaanite city that can be excavated in its entirety because after the city was abandoned, no other city was built over its remains. It is notable because the predominant extra-Canaanite cultural influence is Minoan; Minoan-style frescoes decorate the palace.[38]

List of Canaan's rulers

Names of Canaanite kings or other figures mentioned in historiography or known through archaeology

|

Confirmed archaeologically

Hebrew Bible and other historiography

|

Rulers of Tyre

|

In Jewish and Christian scriptures

Hebrew Bible

In Biblical usage, the name was confined to the country west of the Jordan River. Canaanites were described as living "by the sea, and along by the side of the Jordan" (Book of Numbers 33:51; Book of Joshua 22:9). Canaan was especially identified with Phoenicia (Book of Isaiah 23:11).[39] The Philistines, while an integral part of the Canaanite milieu, do not seem to have been ethnic Canaanites, and were listed in the Table of Nations as descendants of Mizraim; the Arameans, Moabites, Ammonites, Midianites and Edomites were also considered fellow descendants of Shem or Abraham, and distinct from generic Canaanites/Amorites. "Heth", representing the Hittites, is a son of Canaan. The later Hittites spoke an Indo-European language (called Nesili), but their predecessors the Hattians had spoken a little-known language (Hattili), of uncertain affinities.

The Horites, formerly of Mount Seir, were implied to be Canaanite (Hivite), although unusually there is no direct confirmation of this in the narrative. The Hurrians, based in Upper Mesopotamia, spoke the Hurrian language. Their language was a language isolate.

In the Bible, the renaming of the Land of Canaan as the Land of Israel marks the Israelite conquest of the Promised Land.[40]

Canaan and the Canaanites are mentioned some 160 times in the Hebrew Bible, mostly in the Pentateuch and the books of Joshua and Judges.[41]

An ancestor called Canaan first appears as one of Noah's grandsons. He appears during the narrative known as the Curse of Ham, in which Canaan is cursed with perpetual slavery because his father Ham had "looked upon" the drunk and naked Noah. The expression "look upon" at times has sexual overtones in the Bible, as in Leviticus 20:11, "The man who lies with his father's wife has uncovered his father's nakedness..." As a result, interpreters have proposed a variety of possibilities as to what kind of transgression has been committed by Ham, including the possibility that maternal incest is implied.[42]

God later promises the land of Canaan to Abraham, and eventually delivers it to descendants of Abraham, the Israelites.[41] The biblical history has become increasingly problematic as the archaeological and textual evidence supports the idea that the early Israelites were in fact themselves Canaanites.[41]

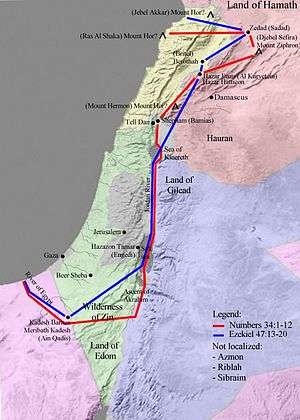

The Hebrew Bible lists borders for the land of Canaan. The Book of Numbers, 34:2, includes the phrase "the land of Canaan as defined by its borders." The borders are then delineated in Numbers 34:3–12. The term "Canaanites" in biblical Hebrew is applied especially to the inhabitants of the lower regions, along the sea coast and on the shores of the Jordan River, as opposed to the inhabitants of the mountainous regions. By the Second Temple period (530 BC–70 AD),[43] "Canaanite" in the Hebrew language had come to be not an ethnic designation, so much as a general synonym for "merchant", as it is interpreted in, for example, Book of Job 40:30, or Book of Proverbs 31:24.[44]

John N. Oswalt notes that "Canaan consists of the land west of the Jordan and is distinguished from the area east of the Jordan." Oswalt then goes on to say that in Scripture, Canaan "takes on a theological character" as "the land which is God's gift" and "the place of abundance".[45]

The Hebrew Bible describes the Israelite conquest of Canaan in the "Former Prophets" (Nevi'im Rishonim, נביאים ראשונים ), viz. the books of Joshua, Judges, Samuel, and Kings. These books of the Old Testament canon give the narrative of the Israelites after the death of Moses and their entry into Canaan under the leadership of Joshua.[46] In 586 BC, the Kingdom of Judah was annexed into the Neo-Babylonian Empire. The city of Jerusalem fell after a siege which lasted either eighteen or thirty months.[47] By 586 BC, much of Judah was devastated, and the former kingdom suffered a steep decline of both economy and population.[48] The descendants of the Israelites thus lost control of the land. These narratives of the Former Prophets are also "part of a larger work, called the Deuteronomistic History".[49]

The passage in the Book of Genesis often called the Table of Nations presents the Canaanites as descendants of an eponymous ancestor called Canaan, the son of Ham and grandson of Noah (Hebrew: כְּנַעַן, Knaan). (Genesis 10:15–19) states:

Canaan is the father of Sidon, his firstborn; and of the Hittites, Jebusites, Amorites, Girgashites, Hivites, Arkites, Sinites, Arvadites, Zemarites, and Hamathites. Later the Canaanite clans scattered, and the borders of Canaan reached [across the Mediterranean coast] from Sidon toward Gerar as far as Gaza, and then [inland around the Jordan Valley ] toward Sodom, Gomorrah, Admah and Zeboiim, as far as Lasha.

The Sidon whom the Table identifies as the firstborn son of Canaan has the same name as that of the coastal city of Sidon in Lebanon. This city dominated the Phoenician coast, and may have enjoyed hegemony over a number of ethnic groups, who are said to belong to the "Land of Canaan".

Similarly, Canaanite populations are said to have inhabited:

- the Mediterranean coastlands (Joshua 5:1), including Lebanon corresponding to Phoenicia (Isaiah 23:11) and the Gaza Strip corresponding to Philistia (Zephaniah 2:5).

- the Jordan Valley (Joshua 11:3, Numbers 13:29, Genesis 13:12).

The Canaanites (Hebrew: כנענים, Modern: Kna'anim, Tiberian: Kənaʻănîm) are said to have been one of seven regional ethnic divisions or "nations" driven out by the Israelites following the Exodus. Specifically, the other nations include the Hittites, the Girgashites, the Amorites, the Perizzites, the Hivites, and the Jebusites (Deuteronomy 7:1).

According to the Book of Jubilees, the Israelite conquest of Canaan is attributed to Canaan's steadfast refusal to join his elder brothers in Ham's allotment beyond the Nile, and instead "squatting" on the eastern shores of the Mediterranean Sea, within the inheritance delineated for Shem. Canaan thus incurs a further curse from Noah for disobeying the agreed apportionment of land.[50]

One of the 613 commandments (precisely n. 596) prescribes that no inhabitants of the cities of six Canaanite nations, the same as mentioned in 7:1, minus the Girgashites, were to be left alive.

While the Hebrew Bible distinguishes the Canaanites ethnically from the ancient Israelites, modern scholars Jonathan Tubb and Mark S. Smith have theorized—based on their archaeological and linguistic interpretations—that the Kingdom of Israel and the Kingdom of Judah represented a subset of Canaanite culture.[6][7]

The name "Canaanites" is attested, many centuries later, as the endonym of the people later known to the Ancient Greeks from c. 500 BC as Phoenicians,[5] and following the emigration of Canaanite-speakers to Carthage (founded in the 9th century BC), was also used as a self-designation by the Punics (chanani) of North Africa during Late Antiquity. This mirrors usage of the names Canaanites and Phoenicians in later books of the Hebrew Bible (such as at the end of the Book of Zechariah, where it is thought to refer to a class of merchants or to non-monotheistic worshippers in Israel or neighbouring Sidon and Tyre), as well as in its single independent usage in the New Testament (where it alternates with the term "Syrophoenician" in two parallel passages).

New Testament

Canaan (Biblical Greek: Χανάαν, Khanáan[1]) is used only twice in the New Testament: both times in Acts of the Apostles when paraphrasing Old Testament stories.[51] Additionally, the derivative Khananaia (Χαναναία, "Canaanite woman") is used in Matthew's version of the exorcism of the Syrophoenician woman's daughter, while the Gospel of Mark uses the term Syrophoenician (Συροφοινίκισσα).

Greco-Roman historiography

The Greek term Phoenicia is first attested in the first two works of Western literature, Homer's Iliad and Odyssey. It does not occur in the Hebrew Bible, but occurs three times in the New Testament in the Book of Acts.[53] In the 6th century BC, Hecataeus of Miletus affirms that Phoenicia was formerly called χνα, a name that Philo of Byblos subsequently adopted into his mythology as his eponym for the Phoenicians: "Khna who was afterwards called Phoinix". Quoting fragments attributed to Sanchuniathon, he relates that Byblos, Berytus and Tyre were among the first cities ever built, under the rule of the mythical Cronus, and credits the inhabitants with developing fishing, hunting, agriculture, shipbuilding and writing.

Coins of the city of Beirut / Laodicea bear the legend, "Of Laodicea, a metropolis in Canaan"; these coins are dated to the reign of Antiochus IV (175–164 BC) and his successors until 123 BC.[52]

Saint Augustine also mentions that one of the terms the seafaring Phoenicians called their homeland was "Canaan". Augustine also records that the rustic people of Hippo in North Africa retained the Punic self-designation Chanani.[54][55] Since 'punic' in Latin also meant 'non-Roman', some scholars however argue that the language referred to as Punic in Augustine may have been Libyan.[56]

The Greeks also popularized the term Palestine, named after the Philistines or the Aegean Pelasgians, for roughly the region of Canaan, excluding Phoenicia, with Herodotus' first recorded use of Palaistinê, c. 480 BC. From 110 BC, the Hasmoneans extended their authority over much of the region, creating a Judean-Samaritan-Idumaean-Ituraean-Galilean alliance. The Judean (Jewish, see Ioudaioi) control over the wider area resulted in it also becoming known as Judaea, a term that had previously only referred to the smaller region of the Judean Mountains, the allotment of the Tribe of Judah and heartland of the former Kingdom of Judah.[57][58] Between 73–63 BC, the Roman Republic extended its influence into the region in the Third Mithridatic War, conquering Judea in 63 BC, and splitting the former Hasmonean Kingdom into five districts. Around 130–135 AD, as a result of the suppression of the Bar Kochba revolt, the province of Iudaea was joined with Galilee to form new province of Syria Palaestina. There is circumstantial evidence linking Hadrian with the name change,[59] although the precise date is not certain,[59] and the interpretation of some scholars that the name change may have been intended "to complete the dissociation with Judaea"[60][61] is disputed.[62]

Archeology

Early and Middle Bronze Age

A disputed reference to Lord of ga-na-na in the Semitic Ebla tablets (dated 2350 BC) from the archive of Tell Mardikh has been interpreted by some scholars to mention the deity Dagon by the title "Lord of Canaan"[63] If correct, this would suggest that Eblaites were conscious of Canaan as an entity by 2500 BC.[64] Jonathan Tubb states that the term ga-na-na "may provide a third-millennium reference to Canaanite", while at the same time stating that the first certain reference is in the 18th century BC.[6]:15 See Ebla-Biblical controversy for further details.

A letter from Mut-bisir to Shamshi-Adad I (c. 1809 – 1776 BC) of the Old Assyrian Empire (2025–1750 BC) has been translated: "It is in Rahisum that the brigands (habbatum) and the Canaanites (Kinahnum) are situated". It was found in 1973 in the ruins of Mari, an Assyrian outpost at that time in Syria.[6][65] Additional unpublished references to Kinahnum in the Mari letters refer to the same episode.[66] Whether the term Kinahnum refers to people from a specific region or rather people of "foreign origin" has been disputed,[67][68] such that Robert Drews states that the "first certain cuneiform reference" to Canaan is found on the Alalakh statue of King Idrimi (below).[69]

A reference to Ammiya being "in the land of Canaan" is found on the Statue of Idrimi (16th century BC) from Alalakh in modern Syria. After a popular uprising against his rule, Idrimi was forced into exile with his mother's relatives to seek refuge in "the land of Canaan", where he prepared for an eventual attack to recover his city. The other references in the Alalakh texts are:[66]

- AT 154 (unpublished)

- AT 181: A list of 'Apiru people with their origins. All are towns, except for Canaan

- AT 188: A list of Muskenu people with their origins. All are towns, except for three lands including Canaan

- AT 48: A contract with a Canaanite hunter.

Amarna letters

References to Canaanites are also found throughout the Amarna letters of Pharaoh Akhenaten c. 1350 BC. In these letters, some of which were sent by governors and princes of Canaan to their Egyptian overlord Akhenaten (Amenhotep IV) in the 14th century BC, are found, beside Amar and Amurru (Amorites), the two forms Kinahhi and Kinahni, corresponding to Kena and Kena'an respectively, and including Syria in its widest extent, as Eduard Meyer has shown. The letters are written in the official and diplomatic East Semitic Akkadian language of Assyria and Babylonia, though "Canaanitish" words and idioms are also in evidence. The known references are:[66]

- EA 8: Letter from Burna-Buriash II to Akhenaten, explaining that his merchants "were detained in Canaan for business matters", robbed and killed "in Hinnatuna of the land of Canaan" by the rulers of Acre and Shamhuna, and asks for compensation because "Canaan is your country"

- EA 9: Letter from Burna-Buriash II to Tutankhamun, "all the Canaanites wrote to Kurigalzu saying 'come to the border of the country so we can revolt and be allied with you'"

- EA 30: Letter from Tushratta: "To the kings of Canaan... Provide [my messenger] with safe entry into Egypt"

- EA 109: Letter of Rib-Hadda: "Previously, on seeing a man from Egypt, the kings of Canaan fled before him, but now the sons of Abdi-Ashirta make men from Egypt prowl about like dogs"

- EA 110: Letter of Rib-Hadda: "No ship of the army is to leave Canaan"

- EA 131: Letter of Rib-Hadda: "If he does not send archers, they will take [Byblos] and all the other cities, and the lands of Canaan will not belong to the king. May the king ask Yanhamu about these matters."

- EA 137: Letter of Rib-Hadda: "If the king neglects Byblos, of all the cities of Canaan not one will be his"

- EA 367: "Hani son (of) Mairēya, "chief of the stable" of the king in Canaan"

- EA 162: Letter to Aziru: "You yourself know that the king does not want to go against all of Canaan when he rages"

- EA 148: Letter from Abimilku to the Pharaoh: "[The king] has taken over the land of the king for the 'Apiru. May the king ask his commissioner, who is familiar with Canaan"

- EA 151: Letter from Abimilku to the Pharaoh: "The king, my lord wrote to me: 'write to me what you have heard from Canaan'." Abimilku describes in response what has happened in eastern Cilicia (Danuna), the northern coast of Syria (Ugarit), in Syria (Qadesh, Amurru, and Damascus) as well as in Sidon.

Other Late Bronze Age mentions

Text RS 20.182 from Ugarit is a copy of a letter of the king of Ugarit to Ramesses II concerning money paid by "the sons of the land of Ugarit" to the "foreman of the sons of the land of Canaan (*kn'ny)" According to Jonathan Tubb, this suggests that the Semitic people of Ugarit, contrary to much modern opinion, considered themselves to be non-Canaanite.[6]:16

The other Ugarit reference, KTU 4.96, shows a list of traders assigned to royal estates, of which one of the estates had three Ugaritans, an Ashdadite, an Egyptian and a Canaanite.[66]

Ashur tablets

A Middle Assyrian letter during the reign of Shalmaneser I includes a reference to the "travel to Canaan" of an Assyrian official.[66]

Hattusa letters

Four references are known from Hattusa:[66]

- An evocation to the Cedar Gods: Includes reference to Canaan alongside Sidon, Tyre and possibly Amurru

- KBo XXVIII 1: Ramesses II letter to Hattusili III, in which Ramesses suggested he would meet "his brother" in Canaan and bring him to Egypt

- KUB III 57 (also KUB III 37 + KBo I 17): Broken text which may refer to Canaan as an Egyptian sub-district

- KBo I 15+19: Ramesses II letter to Hattusili III, describing Ramesses' visit to the "land of Canaan on his way to Kinza and Harita

Egyptian Hieroglyphic and Hieratic (1500–1000 BC)

During the 2nd millennium BC, Ancient Egyptian texts use the term Canaan to refer to an Egyptian-ruled colony, whose boundaries generally corroborate the definition of Canaan found in the Hebrew Bible, bounded to the west by the Mediterranean Sea, to the north in the vicinity of Hamath in Syria, to the east by the Jordan Valley, and to the south by a line extended from the Dead Sea to around Gaza. Nevertheless, the Egyptian and Hebrew uses of the term are not identical: the Egyptian texts also identify the coastal city of Qadesh in north west Syria near Turkey as part of the "Land of Canaan", so that the Egyptian usage seems to refer to the entire Levantine coast of the Mediterranean Sea, making it a synonym of another Egyptian term for this coastland, Retjenu.

Lebanon, in northern Canaan, bordered by the Litani river to the watershed of the Orontes River, was known by the Egyptians as upper Retjenu.[70] In Egyptian campaign accounts, the term Djahi was used to refer to the watershed of the Jordan river. Many earlier Egyptian sources also mention numerous military campaigns conducted in Ka-na-na, just inside Asia.[71]

Archaeological attestation of the name Canaan in Ancient Near Eastern sources relates almost exclusively to the period in which the region operated as a colony of the New Kingdom of Egypt (16th–11th centuries BC), with usage of the name almost disappearing following the Late Bronze Age collapse (c. 1206–1150 BC).[72] The references suggest that during this period the term was familiar to the region's neighbors on all sides, although scholars have disputed to what extent such references provide a coherent description of its location and boundaries, and regarding whether the inhabitants used the term to describe themselves.[73]

16 references are known in Egyptian sources, from the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt onwards.[66]

- Amenhotep II inscriptions: Canaanites are included in a list of prisoners of war

- Three topographical lists

- Papyrus Anastasi I 27,1" refers to the route from Sile to Gaza "the [foreign countries] of the end of the land of Canaan"

- Merneptah Stele

- Papyrus Anastasi IIIA 5–6 and Papyrus Anastasi IV 16,4 refer to "Canaanite slaves from Hurru"

- Papyrus Harris[74] After the collapse of the Levant under the so-called "Peoples of the Sea" Ramesses III (c. 1194 BC) is said to have built a temple to the god Amen to receive tribute from the southern Levant. This was described as being built in Pa-Canaan, a geographical reference whose meaning is disputed, with suggestions that it may refer to the city of Gaza or to the entire Egyptian-occupied territory in the south west corner of the Near East.[75]

Later sources

Padiiset's Statue is the last known Egyptian reference to Canaan, a small statuette labelled "Envoy of the Canaan and of Peleset, Pa-di-Eset, the son of Apy". The inscription is dated to 900–850 BC, more than 300 years after the preceding known inscription.[76]

During the period from c. 900–330 BC, the dominant Neo-Assyrian and Achaemenid Empire make no mention of Canaan.[77]

Legacy

"Canaan" is used as a synonym of the Promised Land; for instance, it is used in this sense in the hymn, Canaan's Happy Shore, with the lines: "Oh, brothers, will you meet me, (3x)/On Canaan's happy shore," a hymn set to the tune later used in The Battle Hymn of the Republic.

In the 1930s and 1940s, some Revisionist Zionist intellectuals in Palestine founded the ideology of Canaanism, which sought to create a unique Hebrew identity, rooted in ancient Canaanite culture, rather than a Jewish one.

See also

- Amarna letters–localities and their rulers

- Canaanite religion

- History of the name Palestine

- Names of the Levant

- Curse of Canaan

Notes

- The current scholarly edition of the Greek Old Testament spells the word without any accents, cf. Septuaginta : id est Vetus Testamentum graece iuxta LXX interpretes. 2. ed. / recogn. et emendavit Robert Hanhart. Stuttgart : Dt. Bibelges., 2006 ISBN 978-3-438-05119-6. However, in modern Greek the accentuation is Xαναάν, while the current (28th) scholarly edition of the New Testament has Xανάαν.

- Brody, Aaron J.; King, Roy J. (1 December 2013). "Genetics and the Archaeology of Ancient Israel". Wayne State University. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- Dever, William G. (2006). Who Were the Early Israelites and Where Did They Come From?. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 219. ISBN 9780802844163.

Canaanite is by far the most common ethnic term in the Hebrew Bible. The pattern of polemics suggests that most Israelites knew that they had a shared common remote ancestry and once common culture.

- Dozeman, Thomas B. (2015). Joshua 1–12: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary. Yale University Press. p. 259. ISBN 9780300172737. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

In the ideology of the book of Joshua, the Canaanites are included in the list of nations requiring extermination (3:10; 9:1; 24:11).

- Drews 1998, pp. 48–49: "The name 'Canaan' did not entirely drop out of usage in the Iron Age. Throughout the area that we—with the Greek speakers—prefer to call 'Phoenicia', the inhabitants in the first millennium BC called themselves 'Canaanites'. For the area south of Mt. Carmel, however, after the Bronze Age ended references to 'Canaan' as a present phenomenon dwindle almost to nothing (the Hebrew Bible of course makes frequent mention of 'Canaan' and 'Canaanites', but regularly as a land that had become something else, and as a people who had been annihilated)."

- Tubb, Johnathan N. (1998). Canaanites. British Museum People of the Past. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 9780806131085. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- Smith, Mark S. (2002). The Early History of God: Yahweh and Other Deities of Ancient Israel. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 6–7. ISBN 9780802839725. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

Despite the long regnant model that the Canaanites and Israelites were people of fundamentally different culture, archaeological data now casts doubt on this view. The material culture of the region exhibits numerous common points between Israelites and Canaanites in the Iron I period (c. 1200 – 1000 BC). The record would suggest that the Israelite culture largely overlapped with and derived from Canaanite culture... In short, Israelite culture was largely Canaanite in nature. Given the information available, one cannot maintain a radical cultural separation between Canaanites and Israelites for the Iron I period.

- Rendsberg, Gary (2008). "Israel without the Bible". In Greenspahn, Frederick E. (ed.). The Hebrew Bible: New Insights and Scholarship. NYU Press. pp. 3–5. ISBN 9780814731871. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- Asheri, David; Lloyd, Alan; Corcella, Aldo (2007). A Commentary on Herodotus, Books 1–4. Oxford University Press. p. 75. ISBN 978-0198149569.

- Wilhelm Gesenius, Hebrew Lexicon, 1833

- Tristram, Henry Baker (1884). Bible Places: Or, The Topography of the Holy Land. p. 336. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- Drews 1998, pp. 47–49:"From the Egyptian texts it appears that the whole of Egypt’s province in the Levant was called ‘Canaan’, and it would perhaps not be incorrect to understand the term as the name of that province...It may be that the term began as a Northwest Semitic common noun, ‘the subdued, the subjugated’, and that it then evolved into the proper name of the Asiaticland that had fallen under Egypt’s dominion (just as the first Roman province in Gaul eventually became Provence)"

- Drews 1998, p. 48: "Until E.A. Speiser proposed that the name ‘Canaan’ was derived from the (unattested) word kinahhu, which Speiser supposed must have been an Akkadian term for reddish-blue or purple, Semiticists regularly explained ‘Canaan’ (Hebrew këna‘an; elsewhere in Northwest Semitic kn‘n) as related to the Aramaic verb kn‘: ‘to bend down, be low’. That etymology is perhaps correct after all. Speiser’s alternative explanation has been generally abandoned, as has the proposal that ‘Canaan’ meant ‘the land of merchants’."

- Lemche 1991, pp. 24–32

- Noll 2001, p. 26

- Steiglitz, Robert (1992). "Migrations in the Ancient Near East". Anthropolgical Science. 3 (101): 263. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- Zarins, Juris (1992). "Pastoral nomadism in Arabia: ethnoarchaeology and the archaeological record—a case study". In Bar-Yosef, Ofer; Khazanov, Anatoly (eds.). Pastoralism in the Levant. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- Pardee, Dennis (2008-04-10). "Ugaritic". In Woodard, Roger D. (ed.). The Ancient Languages of Syria-Palestine and Arabia. Cambridge University Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-139-46934-0. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- Richard, Suzanne (1987). "Archaeological Sources for the History of Palestine: The Early Bronze Age: The Rise and Collapse of Urbanism". The Biblical Archaeologist. 50 (1): 22–43. doi:10.2307/3210081. JSTOR 3210081.

- Lily Agranat-Tamir; et al. (2020). "The Genomic History of the Bronze Age Southern Levant". 181 (5). Cell. pp. 1146–1157. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.024.

- Golden 2009, p. 5

- Woodard, Roger D., ed. (2008). The Ancient Languages of Syria-Palestine and Arabia. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511486890. ISBN 9780511486890..

- Naveh, Joseph (1987). "Proto-Canaanite, Archaic Greek, and the Script of the Aramaic Text on the Tell Fakhariyah Statue". In Miller, Patrick D.; Hanson, Paul D.; et al. (eds.). Ancient Israelite Religion: Essays in Honor of Frank Moore Cross. Fortress Press. p. 101. ISBN 9780800608316. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- Coulmas, Florian (1996). The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Writing Systems. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-21481-6.

- Golden 2009, pp. 5–6

- Mieroop, Marc Van De (2010). A History of Ancient Egypt. John Wiley & Sons. p. 131. ISBN 978-1-4051-6070-4.

- Bard, Kathryn A. (2015). An Introduction to the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. John Wiley & Sons. p. 188. ISBN 978-1-118-89611-2.

- Kamrin, Janice (2009). "The Aamu of Shu in the Tomb of Khnumhotep II at Beni Hassan" (PDF). Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections. Vol. 1:3.

- Curry, Andrew (2018). "The Rulers of Foreign Lands - Archaeology Magazine". www.archaeology.org.

- Golden 2009, pp. 6–7

- Oppenheim, A. Leo (2013). Ancient Mesopotamia: Portrait of a Dead Civilization. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226177670. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- El Amarna letter, EA 189.

- Roux, Georges (1992). Ancient Iraq. Penguin Books. ISBN 9780141938257. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- Killebrew, Ann E. (2003). "Biblical Jerusalem: An Archaeological Assessment". In Killebrew, Ann E.; Vaughn, Andrew G. (eds.). Jerusalem in Bible and Archaeology: The First Temple Period. Society of Biblical Literature. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- Wolfe, Robert. "From Habiru to Hebrews: The Roots of the Jewish Tradition". New English Review. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- Van Seters, John (1987). Abraham in Myth and Tradition. Yale University Press. ISBN 9781626549104.

- Thompson, Thomas L. (2000). Early History of the Israelite People: From the Written & Archaeological Sources. Brill Academic. ISBN 978-9004119437. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- "Remains Of Minoan-Style Painting Discovered During Excavations Of Canaanite Palace". ScienceDaily. 7 December 2009. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- The Septuagint translates "Canaanites" by "Phoenicians", and "Canaan" by the "land of the Phoenicians" (Book of Exodus 16:35; Book of Joshua 5:12). "Canaan" article in the International Standard Bible Encyclopedia online

- Schweid, Eliezer (1985). The Land of Israel: National Home Or Land of Destiny. Translated by Greniman, Deborah. Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press. pp. 16–17. ISBN 978-0-8386-3234-5.

... let us begin by examining the kinds of assertions about the land of Israel that we encounter in persuing [sic] the books of the Bible. ... A third kind of assertion deals with the history of the Land of Israel. Before its settlement by the Israelite tribes, it is called The Land of Canaan

- Killebrew 2005, p. 96

- Johanna Stiebert (20 October 2016). First-Degree Incest and the Hebrew Bible: Sex in the Family. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 106–108. ISBN 978-0-567-26631-6.

- Figures based purely upon scientific dating and the proclivity among some scholars to bypass Jewish sources. However, Jewish tradition avers that the Second Temple stood for only four-hundred and twenty years, i.e. from 352 BCE – 68 CE. See: Maimondes' Questions & Responsa, responsum # 389, Jerusalem 1960 (Hebrew)

- Wilhelm Gesenius, Hebrew Dictionary

- Oswalt, John N. (1980). "כנען". In Harris, R. Laird; Archer, Gleason L.; Waltke, Bruce K. (eds.). Theological Wordbook of the Old Testament. Chicago: Moody. pp. 445–446.

- The Making of the Old Testament Canon. by Lou H. Silberman, The Interpreter’s One-Volume Commentary on the Bible. Abingdon Press – Nashville 1971–1991, p1209

- Malamat, Abraham (1968). "The Last Kings of Judah and the Fall of Jerusalem: An Historical—Chronological Study". Israel Exploration Journal. 18 (3): 137–156. JSTOR 27925138.

The discrepancy between the length of the siege according to the regnal years of Zedekiah (years 9-11), on the one hand, and its length according to Jehoiachin's exile (years 9-12), on the other, can be cancelled out only by supposing the former to have been reckoned on a Tishri basis, and the latter on a Nisan basis. The difference of one year between the two is accounted for by the fact that the termination of the siege fell in the summer, between Nisan and Tishri, already in the 12th year according to the reckoning in Ezekiel, but still in Zedekiah's 11th year which was to end only in Tishri.

- Grabbe, Lester L. (2004). A History of the Jews and Judaism in the Second Temple Period. 1. T&T Clark International. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-567-08998-4. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- by Michael Coogan A brief Introduction to the Old Testament, Oxford University Press New York, 2009, p4

- VanderKam, James C. (2002). From Revelation to Canon: Studies in the Hebrew Bible and Second Temple Literature. BRILL. pp. 491–492. ISBN 978-0-391-04136-3.

- Acts 7:11 and Acts 13:19

- Cohen, Getzel M. (2006). The Hellenistic Settlements in Syria, the Red Sea Basin, and North Africa. University of California Press. p. 205. ISBN 978-0-520-93102-2. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

Berytos, being part of Phoenicia, was under Ptolemaic control until 200 B.C. After the battle of Panion Phoenicia and southern Syria passed to the Seleucids. In the second century B.C. Laodikeia issued both autonomous as well as quasi-autonomous coins. The autonomous bronze coins had a Tyche on the obverse. The reverse often had Poseidon or Astarte standing on the prow of a ship, the letters BH or [lambda alpha] and the monogram [phi], that is, the initials of Berytos/Laodikeia and Phoenicia, and, on a few coins, the Phoenician legend LL'DK' 'S BKN 'N or LL'DK' 'M BKN ’N, which has been read as "Of Laodikcia which is in Canaan" or "Of Laodikcia Mother in Canaan." The quasi-municipal coins—issued under Antiochos IV Epiphanes (175–164 B.c.) and continuing with Alexander I Balas (150–145 B.c.), Demetrios II Nikator (146–138 B.C.), and Alexander II Zabinas (128–123 n.c.)—contained the king's head on the obverse, and on the reverse the name of the king in Greek, the city name in Phoenician (LL'DK' 'S BKN ’N or LL'DK’ 'M BKN 'N), the Greek letters [lambda alpha], and the monogram [phi]. After c.123 B.C. the Phoenician "Of Laodikcia which is in Canaan" / "Of Laodikcia Mother in Canaan" is no longer attested

- The Popular and Critical Bible Encyclopaedia, The three occasions are Acts 11:19, Acts 15:3 and Acts 21:2

- Epistulae ad Romanos expositio inchoate expositio, 13 (Migne, Patrologia Latina, vol.35 p.2096):'Interrogati rustici nostri quid sint, punice respondents chanani.'

- Shaw, Brent D. (2011). Sacred Violence: African Christians and Sectarian Hatred in the Age of Augustine. Cambridge University Press. p. 431. ISBN 9780521196055. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- Ellingsen, Mark (2005). The Richness of Augustine: His Contextual and Pastoral Theology. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 9. ISBN 9780664226183. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- Horbury, William; Davies, W. D.; Sturdy, John, eds. (2008). The Cambridge History of Judaism. 3. Cambridge University Press. p. 210. doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521243773. ISBN 9781139053662. Retrieved 9 October 2018. "In both the Idumaean and the Ituraean alliances, and in the annexation of Samaria, the Judaeans had taken the leading role. They retained it. The whole political–military–religious league that now united the hill country of Palestine from Dan to Beersheba, whatever it called itself, was directed by, and soon came to be called by others, 'the Ioudaioi'"

- Ben-Sasson, Haim Hillel, ed. (1976). A History of the Jewish People. Harvard University Press. p. 226. ISBN 9780674397316. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

The name Judea no longer referred only to....

- Feldman, Louis (1990). "Some Observations on the Name of Palestine". Hebrew Union College Annual. 61: 1–23. ISBN 978-9004104181. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- Lehmann, Clayton Miles (Summer 1998). "Palestine: History". The On-line Encyclopedia of the Roman Provinces. University of South Dakota. Archived from the original on 11 August 2009. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- Sharon, 1998, p. 4. According to Moshe Sharon, "Eager to obliterate the name of the rebellious Judaea", the Roman authorities (General Hadrian) renamed it Palaestina or Syria Palaestina.

- Jacobson, David M. (1999). "Palestine and Israel". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. 313 (313): 65–74. doi:10.2307/1357617. JSTOR 1357617.

- Ahlström, Gösta Werner (1993). The History of Ancient Palestine. Fortress Press. p. 141. ISBN 9780800627706. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- Dahood, Mitchell J. (1978). "Ebla, Ugarit and the Old Testament". Congress Volume, International Organization for Study of the Old Testament. p. 83. Retrieved 9 October 2018..

- Dossin, Georges (1973). "Une mention de Cananéens dans une lettre de Mari". Syria (in French). Institut Francais du Proche-Orient. 50 (3/4): 277–282. doi:10.3406/syria.1973.6403. JSTOR 4197896.

- Na'aman 2005, pp. 110–120.

- Lemche, pp. 27–28: "However, all but one of the references belong to the second half of the 2nd millennium BC, the one exception being the mention of some Canaanites in a document from Marl from the 18th century BC. In this document we find a reference to LUhabbatum u LUKi-na-ah-num. The wording of this passage creates some problems as to the identity of these 'Canaanites', because of the parallelism between LUKh-na-ah-num and LUhabbatum, which is unexpected. The Akkadian word habbatum, the meaning of which is actually 'brigands', is sometimes used to translate the Sumerian expression SA.GAZ, which is normally thought to be a logogram for habiru, 'Hebrews'. Thus there is some reason to question the identity of the 'Canaanites' who appear in this text from Marl We may ask whether these people were called 'Canaanites' because they were ethnically of another stock than the ordinary population of Mari, or whether it was because they came from a specific geographical area, the land of Canaan. However, because of the parallelism in this text between LUhabbatum and LUKi-na-ah-num, we cannot exclude the possibility that the expression 'Canaanites' was used here with a sociological meaning. It could be that the word 'Canaanites' was in this case understood as a sociological designation of some sort which shared at least some connotations with the sociological term habiru. Should this be the case, the Canaanites of Marl may well have been refugees or outlaws rather than ordinary foreigners from a certain country (from Canaan). Worth considering is also Manfred Weippert's interpretation of the passage LUhabbatum u LUKi-na-ah-num—literally 'Canaanites and brigands'—as 'Canaanite brigands', which may welt mean 'highwaymen of foreign origin', whether or not they were actually Canaanites coming from Phoenicia."

- Weippert, Manfred. "Kanaan". Reallexikon der Assyriologie. 5. p. 352. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- Drews 1998, p. 46: "An eighteenth-century letter from Mari may refer to Canaan, but the first certain cuneiform reference appears on a statue base of Idrimi, king of Alalakh c. 1500 BC."

- Breasted, J.H. (1906). Ancient records of Egypt. University of Illinois Press.

- Redford, Donald B. (1993). Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691000862. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- Drews 1998, p. 61: "The name 'Canaan', never very popular, went out of vogue with the collapse of the Egyptian empire."

- For details of the disputes, see the works of Lemche and Na'aman, the main protagonists.

- Higginbotham, Carolyn (2000). Egyptianization and Elite Emulation in Ramesside Palestine: Governance and Accommodation on the Imperial Periphery. Brill Academic Pub. p. 57. ISBN 978-90-04-11768-6. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- Hasel, Michael (Sep 2010). "Pa-Canaan in the Egyptian New Kingdom: Canaan or Gaza?". University of Arizona Institutional Repository Logo Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections. 1 (1). Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- Drews 1998, p. 49a:"In the Papyrus Harris, from the middle of the twelfth century, the late Ramesses III claims to have built for Amon a temple in 'the Canaan' of Djahi. More than three centuries later comes the next—and very last—Egyptian reference to 'Canaan' or 'the Canaan': a basalt statuette, usually assigned to the Twenty-Second Dynasty, is labeled, 'Envoy of the Canaan and of Palestine, Pa-di-Eset, the son of Apy'."

- Drews 1998, p. 49b:"Although New Assyrian inscriptions frequently refer to the Levant, they make no mention of ‘Canaan’. Nor do Persian and Greek sources refer to it."

Bibliography

- Bishop Moore, Megan; Kelle, Brad E. (2011). Biblical History and Israel's Past: The Changing Study of the Bible and History. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-6260-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Buck, Mary Ellen (2019). The Canaanites: Their History and Culture from Texts and Artifacts. Cascade Books. p. 114. ISBN 9781532618048.

- Coogan, Michael D. (1978). Stories from Ancient Canaan. Westminster Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-3108-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Day, John (2002). Yahweh and the Gods and Goddesses of Canaan. Continuum. ISBN 978-0-8264-6830-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Drews, Robert (1998). "Canaanites and Philistines". Journal for the Study of the Old Testament. 81: 39–61.

- Finkelstein, Israel (1996). "Towards a New Periodization and Nomenclature of the Archaeology of the Southern Levant". In Cooper, Jerrold S.; Schwartz, Glenn M. (eds.). The Study of the Ancient Near East in the Twenty-First Century. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-0-931464-96-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Golden, Jonathan M. (2009). Ancient Canaan and Israel: An Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-537985-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Killebrew, Ann E. (2005). Biblical Peoples and Ethnicity. SBL. ISBN 978-1-58983-097-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lemche, Niels-Peter (1991). The Canaanites and their Land: The Tradition of the Canaanites. Continuum. ISBN 978-0-567-45111-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Na'aman, Nadav (2005). Canaan in the 2nd Millennium B.C.E. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1-57506-113-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Noll, K.L. (2001). Canaan and Israel in Antiquity: An Introduction. Continuum. ISBN 978-1-84127-318-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Smith, Mark S. (2002). The Early History of God. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-9004119437.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tubb, Jonathan N. (1998). Canaanites. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-8061-3108-5.

The Canaanites and Their Land.

CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- Canaan & Ancient Israel, University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. Explores their identities (land-time, daily life, economy & religion) in pre-historical times through the material remains that they have left behind.

- Catholic Encyclopedia.

- Antiquities of the Jews by Flavius Josephus.

- When Canaanites and Philistines Ruled Ashkelon Biblical Archaeology Society

- The Nakedness of Noah and the Cursing of Canaan (Genesis 9:18-10:32)

.jpg)