Great Mosque of Gaza

The Great Mosque of Gaza (Arabic: جامع غزة الكبير, transliteration: Jāmaʿ Ghazza al-Kabīr) also known as the Great Omari Mosque (Arabic: المسجد العمري الكبير, transliteration: Jāmaʿ al-ʿUmarī al-Kabīr) is the largest and oldest mosque in the Gaza Strip, located in Gaza's old city.

| Great Mosque of Gaza Great Omari Mosque | |

|---|---|

| |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Islam |

| District | Gaza Governorate |

| Province | Gaza Strip |

| Region | Levant |

| Status | Active |

| Location | |

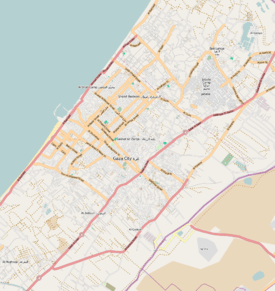

| Location | |

Location within Gaza | |

| Geographic coordinates | 31°30′15.13″N 34°27′52.08″E |

| Architecture | |

| Type | Mosque |

| Style | Mamluk, Italian Gothic |

| Completed | 1340,[1] then early 16th century[2] (the original mosque was completed in the 7th century[3]) |

| Specifications | |

| Minaret(s) | 1 |

| Materials | Sandstone (exterior structure), marble and plaster tiles (entrance and interior structure), olive wood |

| Website | |

| Official website | |

Believed to stand on the site of an ancient Philistine temple, the site was used by the Byzantines to erect a church in the 5th century, but after the Muslim conquest in the 7th century, it was transformed into a mosque. Described as "beautiful" by an Arab geographer in the 10th century, the Great Mosque's minaret was toppled in an earthquake in 1033. In 1149, the Crusaders built a large church, but it was mostly destroyed by the Ayyubids in 1187, and then rebuilt as a mosque by the Mamluks in the early 13th century. It was destroyed by the Mongols in 1260, then soon restored only for it to be destroyed by an earthquake at the end of the century. The Great Mosque was restored again by the Ottomans roughly 300 years later. Severely damaged after British bombardment during World War I, the mosque was restored in 1925 by the Supreme Muslim Council.

Location

The Great Mosque is situated in the Daraj Quarter of the Old City in Downtown Gaza at the eastern end of Omar Mukhtar Street, southeast of Palestine Square.[3][4] Gaza's Gold Market is located adjacent to it on the south side, while to the northeast is the Katib al-Wilaya Mosque and to the east, on Wehda Street, is a girls' school.[5]

History

Legendary Philistine roots

According to tradition, the mosque stands on the site of the Philistine temple dedicated to Dagon—the god of fertility—which Samson toppled in the Book of Judges. Later, a temple dedicated to Marnas—god of rain and grain—was erected.[7][8] Local legend today claims that Samson is buried under the present mosque.[2]

Byzantine church

The building was constructed in 406 AD as a large Byzantine church by Empress Aelia Eudocia,[8][9] although it is also a possible that the church was built by Emperor Marcian. The church appeared on the 6th-century Madaba Map of the Holy Land.[9]

Early Muslim mosque

The Byzantine church was transformed into a mosque in the 7th century by Omar ibn al-Khattab's generals,[3][10] in the early years of Rashidun rule.[9] The mosque is still alternatively named "al-Omari", in honour of Omar ibn al-Khattab who was caliph during the Muslim conquest of Palestine.[3] In 985, during Abbasid rule, Arab geographer al-Muqaddasi wrote that the Great Mosque was a "beautiful mosque."[9][11][12] On 5 December 1033, an earthquake caused the pinnacle of the mosque's minaret to collapse.[13]

Crusader church

In 1149 the Crusaders, who had conquered Gaza in 1100, built a large church atop the ruins of the church upon a decree by Baldwin III of Jerusalem.[14] However, in William of Tyre's descriptions of grand Crusader churches, it is not mentioned.[9] Of the Great Mosque's three aisles today, it is believed that portions of two of them had formed part of the Crusader church.[14]

Based on a Jewish bas-relief accompanied by a Hebrew and Greek inscription[6] carved on the upper tier of one of the building's columns, it was suggested in the late 19th century that the upper pillars of the building were brought from a 3rd-century Jewish synagogue in Caesarea Maritima.[15] However, the discovery of a 6th-century synagogue at Maiumas, the ancient port of Gaza, in the 1960s make local re-use of this column much likelier. The relief on the column depicted Jewish cultic objects - a menorah, a shofar, a lulav and etrog - surrounded by a decorative wreath, and the inscription read "Hananyah son of Jacob" in both Hebrew and Greek.[6] The relief has been destroyed sometime between 1973-1996 and the stone has been smoothed over.[16]

In 1187 the Ayyubids under Saladin wrested control of Gaza from the Crusaders and destroyed the church.[17]

Mamluk mosque

The Mamluks reconstructed the mosque in the 13th century, but in 1260, the Mongols destroyed it.[12] It was rebuilt thereafter, but in 1294, an earthquake caused its collapse.[2] Extensive renovations centered on the iwan were undertaken by the governor Sunqur al-Ala'i during the sultanate of Husam ad-Din Lajin between 1297-99.[18] A later Mamluk governor of the city, Sanjar al-Jawli, commissioned the restoration of the Great Mosque sometime between 1311 and 1319.[9][19] The Mamluks finally rebuilt the mosque completely in 1340.[1] In 1355 Muslim geographer Ibn Battuta noted the mosque's former existence as "a fine Friday mosque," but also says that al-Jawli's mosque was "well-built."[20] Inscriptions on the mosque bear the signatures of the Mamluk sultans al-Nasir Muhammad (dated 1340), Qaitbay (dated May 1498), Qansuh al-Ghawri (dated 1516), and the Abbasid caliph al-Musta'in Billah (dated 1412).[21]

Ottoman period

In the 16th century the mosque was restored after apparent damage in the previous century; the Ottomans commissioned its restoration and also built six other mosques in the city. They had been in control of Palestine since 1517.[2] The interior bears an inscription of the name of the Ottoman governor of Gaza, Musa Pasha, brother of deposed Husayn Pasha, dating from 1663.[10]

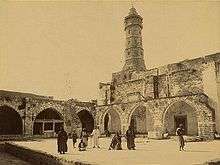

Some Western travelers in the late 19th century reported that the Great Mosque was the only structure in Gaza worthy of historical or architectural note.[22][23] The Great Mosque was severely damaged by Allied forces while attacking the Ottoman positions in Gaza during World War I. The British claimed that there were Ottoman munitions stored in the mosque and its destruction was caused when the munitions were ignited by the bombardment.[24]

British Mandate

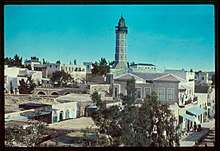

Under the supervision of former Gaza mayor Said al-Shawa,[24] it was restored by the Supreme Muslim Council in 1926-27.[25]

In 1928, the Supreme Muslim Council held a mass demonstration involving both local Muslims and Christians at the Great Mosque in order to rally support for boycotting elections and participation in the Legislative Assembly of the British Mandate of Palestine government. To increase the number of people in the rally, they ordered all the mosques in one of Gaza's quarters to temporarily close.[26]

After 1948

The ancient inscriptions and bas-relief of Jewish religious symbols were allegedly chiseled away intentionally at some stage between 1987 and 1993.[27] During the Battle of Gaza between the Palestinian organizations of Hamas and Fatah, the mosque's pro-Hamas imam Mohammed al-Rafati was shot dead by Fatah gunmen on June 12, 2007, in retaliation for the killing of an official of Mahmoud Abbas's presidential guard by Hamas earlier that day.[28] The mosque is still active and serves as an emotional and physical support base for Gaza's residents and a focal point of Palestinian pride.[10]

Architecture

The Great Mosque has an area of 4,100 square metres (44,000 sq ft).[10][17] Most of the general structure is constructed from local marine sandstone known as kurkar.[29] The mosque forms a large sahn ("courtyard") surrounded by rounded arches.[17] The Mamluks, and later the Ottomans, had the south and southeastern sides of the building expanded.[5]

Over the door of the mosque is an inscription containing the name of Mamluk sultan Qalawun and there are also inscriptions containing the names of the sultans Lajin and Barquq.[30]

Interior

When the building was transformed from a church into a mosque, most of the previous Crusader construction was completely replaced, but the mosque's facade with its arched western entrance is a typical piece of Crusader ecclesiastical architecture,[31] and columns within the mosque compound still retain their Italian Gothic style. Some of the columns have been identified as elements of an ancient synagogue, reused as construction material in the Crusader era and still forming part of the mosque.[32] Internally, the wall surfaces are plastered and painted. Marble is used for the western door and the western facade's oculus. The floors are covered with glazed tiles. The columns are also marble and their capitals are built in Corinthian style.[29]

The central nave is groin-vaulted, each bay being separated from one another by pointed transverse arches with rectangular profiles. The nave arcades are carried on cruciform piers with an engaged column on each face, sitting on a raised plinth. The two aisles of the mosque are also groin-vaulted.[29] Ibn Battuta noted that the Great Mosque had a white marble minbar ("pulpit");[20] it still exists today. There is a small mihrab in the mosque with an inscription dating from 1663, containing the name of Musa Pasha, a governor of Gaza during Ottoman rule.[30]

Minaret

The mosque is well known for its minaret, which is square-shaped in its lower half and octagonal in its upper half, typical of Mamluk architectural style. The minaret is constructed of stone from the base to the upper, hanging balcony, including the four-tiered upper half. The pinnacle is mostly made of woodwork and tiles, and is frequently renewed. A simple cupola springs from the octagonal stone drum and is of light construction similar to most mosques in the Levant.[33] The minaret stands on what was the end of the eastern bay of the Crusader church. Its three semicircular apses were transformed into the base of the minaret.[34]

See also

References

- Gaza at the crossroads of civilisations: Gaza timeline Musée d'Art et Histoire, Geneva. 2007-11-07.

- Ring and Salkin, 1994, p.290.

- Gaza- Ghazza Palestinian Economic Council for Development and Reconstruction.

- Travel in Gaza Archived 2013-08-23 at the Wayback Machine MidEastTravelling.

- Winter, 2000, p.429.

- (1896): Archaeological Researches in Palestine 1873-1874, [ARP], translated from the French by J. McFarlane, Palestine Exploration Fund, London. Volume 2, Page 392.

- Daniel Jacobs, Israel and the Palestinian territories, Rough Guides, 1998, p.454.

- Dowling, 1913, p.79.

- Pringle, 1993, pp. 208-209.

- Palestinians pray in the Great Omari Mosque in Gaza. Ma'an News Agency. 2009-08-27.

- al-Muqaddasi quoted in le Strange, 1890, p.442.

- Ring and Salkin, 1994, p.289.

- Elnashai, 2004, p.23.

- Briggs, 1918, p.255.

- Dowling, 1913, p.80.

- Hershel Shanks, Holy Targets: Joseph's Tomb Is Just the Latest, Biblical Archaeology Review 27:01, January-February 2001, via COJS.org, accessed 15 July 2019

- Gaza Monuments Archived 2008-09-21 at the Wayback Machine International Relations Unit. Municipality of Gaza.

- Sharon, 2009, p. 76.

- Great Mosque of Gaza Archived 2011-08-05 at the Wayback Machine ArchNet Digital Library.

- Ibn Battuta quoted in le Strange, 1890, p.442.

- Sharon, 2009, p.33.

- Porter and Murray, 1868, p.250.

- Porter, 1884, p.208.

- Said al-Shawa Gaza Municipality.

- Kupferschmidt, 1987, p.134.

- Kupferschmidt, 1987, p.230.

- Shanks, Hershel. "Peace, Politics and Archaeology". Biblical Archaeology Society.

- Deadly escalation in Fatah-Hamas feud Archived 2007-06-11 at the Wayback Machine Rabinovich, Abraham. The Australian.

- Pringle, 1993, p.211.

- Meyer, 1907, p.111.

- Winter, 2000, p.428.

- Shanks, Hershel. "Peace, Politics and Archaeology". Biblical Archaeology Society

- Sturgis, 1909, pp.197-198.

- Pringle, 1993, p.210.

Bibliography

- Briggs, Martin Shaw (1918), Through Egypt in War-Time, T.F. Unwin

- Dowling, Theodore Edward (1913), Gaza: A City of Many Battles (from the family of Noah to the Present Day), S.P.C.K

- Elnashai, Amr Salah-Eldin (2004), Earthquake Hazard in Lebanon, Imperial College Press, ISBN 1-86094-461-2

- Kupferschmidt, Uri (1987), The Supreme Muslim Council: Islam Under the British Mandate for Palestine, BRILL, ISBN 90-04-07929-7

- Meyer, Martin Abraham (1907), History of the city of Gaza: from the earliest times to the present day, Columbia University Press

- Murray, John; Porter, Josias Leslie (1868), A Handbook for Travellers in Syria and Palestine ..., J. Murray

- Porter, Josias Leslie (1884), The Giant Cities of Bashan: And Syria's Holy Places, T. Nelson and Sons

- Pringle, Denys (1993), The Churches of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: A Corpus, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-39037-0

- Ring, Trudy; Salkin, Robert M.; Schellinger, Paul E. (1994), International Dictionary of Historic Places, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 9781884964039

- Sharon, Moshe (2009). "Handbook of oriental studies: Handbuch der Orientalistik. The Near and Middle East. Corpus inscriptionum Arabicarum Palaestinae (CIAP)". BRILL. ISBN 90-04-17085-5. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - le Strange, Guy (1890), Palestine Under the Moslems: A Description of Syria and the Holy Land from A.D. 650 to 1500, Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund

- Sturgis, Russel (1909), A History of Architecture, The Baker & Taylor Company, ISBN 90-04-07929-7

- Winter, Dave (2000), Israel Handbook: With the Palestinian Authority Areas, Footprint Travel Guides, ISBN 978-1-900949-48-4