Battle of Chonan

The Battle of Chonan was the third engagement between United States and North Korean forces during the Korean War. It occurred on the night of July 7/8, 1950 in the village of Chonan in western South Korea. The fight ended in a North Korean victory after intense fighting around the town, which took place throughout the night and into the morning.

The United States Army's 34th Infantry Regiment, 24th Infantry Division was assigned to delay elements of the North Korean People's Army's 4th Infantry Division as it advanced south following its victories at the Battle of Osan and the Battle of Pyongtaek the days before. The regiment emplaced north and south of Chonan attempting to delay the North Koreans in an area where the terrain formed a bottleneck between mountains and the Yellow Sea.

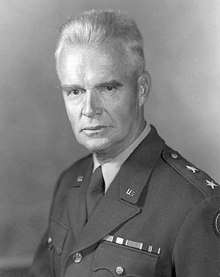

The 3rd Battalion, 34th Infantry set up a defensive perimeter north of the city, and by nightfall was engaged in combat with superior numbers of North Korean troops and tanks. American forces, unable to repulse North Korean armor, soon found themselves in an intense urban fight as columns of North Korean troops, spearheaded by T-34 tanks, entered the town from two directions, cutting off U.S. forces. The fight resulted in the near destruction of the 3rd Battalion, 34th Infantry as well as the death of the 34th Infantry Regiment's new commander, Colonel Robert R. Martin.

Background

Outbreak of war

On the night of June 25, 1950, 10 divisions of the North Korean People's Army launched a full-scale invasion on the nation's neighbor to the south, the Republic of Korea. The force of 89,000 men moved in six columns, catching the Republic of Korea Army completely by surprise, resulting in a disastrous rout for the South Koreans, who were disorganized, ill-equipped, and unprepared for war.[2] Numerically superior, North Korean forces destroyed isolated resistance from the 38,000 South Korean soldiers on the front, advancing steadily south.[3] Most of South Korea's forces retreated in the face of the invasion, and by June 28, the North Koreans had captured Seoul, South Korea's capital, forcing the government and its shattered forces to withdraw south.[4]

The United Nations Security Council voted to send assistance to the collapsing country. United States President Harry S. Truman subsequently ordered ground troops into the nation.[5] However, U.S. forces in the Far East had been steadily decreasing since the end of World War II five years earlier. At the time, the closest forces were the 24th Infantry Division of the Eighth United States Army, which was performing occupation duty in Kyushu, Japan under the command of William F. Dean. However, the division was under strength, and was only two-thirds the size of its regular wartime size. Most of the 24th Infantry Division's equipment was antiquated due to reductions in military spending following World War II. In spite of these deficiencies, the 24th Infantry Division was ordered into South Korea,[5] with a mission to take the initial "shock" of North Korean advances while the rest of the Eighth Army could arrive in Korea and establish a perimeter.[6]

Early engagements

From the 24th Infantry Division, one battalion was assigned to be airlifted into Korea via C-54 Skymaster transport aircraft and move quickly to block advancing North Korean forces while the remainder of the division was transported to South Korea on ships. The 21st Infantry Regiment was determined to be the most combat-ready of the 24th Infantry Division's three regiments, and the 21st Infantry's 1st Battalion was selected because its commander, Lieutenant Colonel Charles B. Smith, was the most experienced, having commanded a battalion at the Battle of Guadalcanal during World War II.[7] On July 5, Task Force Smith engaged North Korean forces at the Battle of Osan, delaying over 5,000 North Korean infantry for seven hours before being routed and forced back.[8]

During that time, the 34th Infantry Regiment set up a line between the villages of Pyongtaek and Ansong, 10 miles (16 km) south of Osan, to fight the next delaying action against the advancing North Korean forces.[9] 34th Infantry Regiment was similarly unprepared for a fight; in the ensuing action, most of the regiment withdrew to Chonan without ever engaging the enemy.[10] The 1st Battalion, left alone against the North Koreans, resisted their advance in the brief and disastrous Battle of Pyongtaek. The 34th Infantry was unable to stop North Korean armor, because equipment had not arrived that could penetrate the thick armor of the T-34 tank.[11] After a 30-minute fight, the battalion mounted a disorganized retreat, with many soldiers abandoning equipment and running away without resisting the North Korean forces. The U.S. forces at Pyongtaek and Ansong were unable to delay the North Korean force significantly or inflict significant casualties on the enemy.[12][13][14]

Battle

Opening moves

Having pushed back U.S. forces at both Osan and Pyongtaek, the North Korean 4th Infantry Division, supported by elements of the North Korean 105th Armored Division, continued their advance down the Osan–Chonan road, up to 12,000 men strong under division commander Lee Kwon Mu in two infantry regiments supported by dozens of tanks. They were well trained, well equipped, and had high morale following previous victories, giving them advantages over the poorly trained and inexperienced Americans.[15][16]

Following the retreat from Pyongtaek, the scattered 1st Battalion, 34th Infantry retreated to Chonan, where the rest of the 34th Infantry Regiment was located. Also at the town were elements of the 1st Battalion, 21st Infantry that had not made up Task Force Smith at the Battle of Osan.[17] Brigadier General George B. Barth, 24th Infantry Division's artillery commander, ordered the 1st Battalion, 21st Infantry to hold positions 2 miles (3.2 km) south of town before Barth left for Taejon. The 1st Battalion, 34th Infantry was sent to join it. At the same time, L Company of the 3rd Battalion, 34th Infantry was ordered to probe north of the city and meet the advancing elements of the North Korean 4th Infantry Division.[18] Major General Dean, commander of the 24th Infantry Division, telegraphed the command from Taejon, ordering the rest of 3rd Battalion, 34th Infantry to move up behind L Company.[19] Regimental commander Colonel Jay B. Lovless moved north to join L Company, along with newly arrived Colonel Robert R. Martin, a friend of Dean's.[13] Shortly before noon, 1st Battalion, 21st Infantry was ordered to withdraw southeast to Chochiwon to keep the railway and supply line to Chonan open. This left 1st and 3rd Battalions of the 34th Infantry alone in Chonan.[20] By this time, most of the South Korean troops and civilians had abandoned the region, leaving only the U.S. forces to oppose the North Korean Army.[11]

At around 1300, L Company of 3rd Battalion, 34th Infantry was 5 miles (8.0 km) north of Chonan when it was hit with North Korean small arms fire. Around this time, Martin received a message from Dean that around 50 North Korean T-34 tanks were at Ansong, along with a significant number of North Korean trucks. Large numbers of troops were now located in the villages of Myang, Myon and Songhwan-ni, and moving to flank Chonan from both sides.[21] Martin and Lovless returned to the 34th Infantry's command post, as the 3rd Battalion, 34th Infantry began setting up defensive positions several miles north of Chonan under the command of 34th Infantry Operations Officer John J. Dunn.[14] The battalion briefly retreated when around 50 North Korean scouts began assaulting its positions, leaving behind several wounded men and equipment, including a wounded Dunn who was captured by the North Koreans.[22][23] It was two hours before the main North Korean force advanced through this position.[13][24] The battalion returned to Chonan in disorder. By 1700, it re-established defensive positions on the northern and western edges of the town, around a railroad station.[25][26] The 1st Battalion, still disorganized and under-equipped after its engagement at Pyongtaek the day before, remained in defensive positions south of the town. It would not see combat in Chonan.[24][27] Around 1800, Dean ordered Martin to take command of the 34th Infantry Regiment from Lovless.[19]

North Korean attack

Throughout the evening of July 7, North Korean pressure developed from the west edge of town. Around 2000 a column of North Korean tanks and infantry approached the town from the east. The column was hit by shells from the 63rd Field Artillery Battalion, which was supporting the 34th Infantry with 105 mm Howitzers firing white phosphorus and High Explosive Anti Tank shells. The 63rd Field Artillery Battalion was able to destroy two of the tanks, but by midnight the column had infiltrated Chonan.[25] The 63rd Field Artillery continued to fire white phosphorus throughout the night, illuminating the terrain for the U.S. forces and preventing them from being overrun.[11] After midnight, the North Korean force was able to cut off 80 men, including Martin, from the rest of the U.S. force, and Lieutenant Colonel Robert L. Wadlington, the regimental executive officer, took command and contacted Dean requesting additional ammunition. By 0220 on July 8 Martin had returned to the town and the supply road to Taejon was reopened.[24][25]

Within a few hours, a second column of infantry assaulted the town from the northwest. Five or six tanks at the head of the column infiltrated Chonan and began destroying all vehicles in sight, as well as any buildings suspected of harboring Americans. Around 0600, infantry from the northwest column began flooding into the city and engaged in an intense and confused battle with the 3rd Battalion, 34th Infantry Regiment in the streets of Chonan.[26][28] 3rd Battalion managed to destroy two of the tanks with rockets and grenades, but the column was able to cut off two companies of the 3rd Battalion from the rest of the force.[25] Around 0800, Martin was killed by a North Korean tank when he fired a 2.36-inch bazooka at a North Korean T-34 tank at the same time it fired its main cannon at the building he was in. He had been in command of the 34th Infantry Regiment for only 14 hours.[26][29] The tank was undamaged by Martin's shot, as the weapon was obsolete and could not penetrate T-34 armor.[28]

American withdrawal

After Martin's death, the 3rd Battalion, 34th Infantry began to buckle as increasing numbers of North Korean troops flooded into Chonan from the Northwest and eastern roads. The battalion suffered heavy casualties, but was saved by the continuous fire laid down by the 63rd Field Artillery Battalion.[29] Between 0800 and 1000, U.S. units began a disorganized retreat from the town, many soldiers deserting their units and running from the battle.[28] Wadlington, now in command of the 34th Infantry, moved 3rd Battalion to a collecting point south of the town, where 1st Battalion, 34th Infantry was holding a blocking position and had not been engaged.[30] As 3rd Battalion, 34th Infantry began to pull back to rally points, 1st Battalion began to come under mortar fire from North Korean forces, but withdrew without engaging them.[31]

As this was happening, General Dean arrived south of the town with Lieutenant General Walton Walker to observe the conflict, and the final elements of the 34th leave Chonan. Dean ordered the 34th Infantry Regiment to retreat to the Kum River. 3rd Battalion, 34th Infantry, now down to 175 men, had lost two thirds of its strength in Chonan, around 350 men. Most of the battalion's heavy equipment including mortars and machine guns were also lost.[26] The North Korean radio reported 60 Americans were taken prisoner in the town. The regiment began its retreat in the late afternoon, with North Korean forces moving on ridges parallel to the regiment.[30] Most of the battalion moved out on foot and by truck, resting on the evening of July 8 before arriving at the Kum River July 9 and setting up new defensive positions.[28]

Aftermath

The 34th Infantry pulled back to the Kum River, its two battalions having been mauled in the battles of Pyongtaek and Chonan. It was able to delay North Korean forces for 14–20 hours, allowing the 21st Infantry Regiment to set up the next delaying action at Chonui and Chochiwon.[32] The 34th Infantry subsequently set up defensive fortifications along the Kum River, resting for several days until it was engaged in the Battle of Taejon, and were principally in charge of the defense of the city as the weakened 21st Infantry and 19th Infantry were less prepared for the fight. The battle at Taejon resulted in the near destruction of the 24th Infantry Division.[33] Although the force was badly defeated militarily, the 24th Infantry Division accomplished its mission of delaying North Korean forces from advancing until July 20. By that time, American forces had set up a defensive perimeter along the Naktong River and Taegu to the southeast, known as the Pusan Perimeter. This perimeter saw the next phase of the battle and the ultimate defeat of the North Korean army in the Battle of Pusan Perimeter.[34]

Robert R. Martin, the 34th Infantry Regiment's commanding officer during the battle, was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his actions at Chonan, the first such decoration awarded during the Korean War.[29]

References

Citations

- Battle of Cheonan - Martin Park - Cheonan, Korea

- Alexander 2003, p. 1.

- Alexander 2003, p. 2.

- Varhola 2000, p. 2.

- Varhola 2000, p. 3.

- Catchpole 2001, p. 14.

- "Task Force Smith Informational Paper". United States Army Japan. Archived from the original on 2010-08-24. Retrieved 2009-11-29.

- Varhola 2000, p. 4.

- Alexander 2003, p. 62.

- Fehrenbach 2001, p. 74.

- Catchpole 2001, p. 15.

- Gugeler 2005, p. 16.

- Alexander 2003, p. 66.

- Fehrenbach 2001, p. 78.

- Alexander 2003, p. 63.

- Gugeler 2005, p. 12.

- Appleman 1998, p. 81.

- Appleman 1998, p. 82.

- Appleman, p. 83.

- Appleman 1998, p. 89.

- Appleman 1998, p. 84.

- Appleman 1998, p. 85.

- Fehrenbach 2001, p. 79.

- Fehrenbach 2001, p. 80.

- Appleman, p. 86.

- Alexander 2003, p. 67.

- Gugeler 2005, p. 18.

- Fehrenbach 2001, p. 81.

- Appleman 1998, p. 87.

- Appleman 1998, p. 88.

- Gugeler 2005, p. 19.

- Gugeler 2005, p. 20.

- Appleman 1998, p. 90.

- Fehrenbach 2001, p. 101.

Sources

- Alexander, Bevin (2003). Korea: The First War we Lost. Hippocrene Books. ISBN 978-0-7818-1019-7.

- Appleman, Roy E. (1998). South to the Naktong, North to the Yalu: United States Army in the Korean War. Department of the Army. ISBN 978-0-16-001918-0.

- Catchpole, Brian (2001). The Korean War. Robinson Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84119-413-4.

- Fehrenbach, T.R. (2001). This Kind of War: The Classic Korean War History - Fiftieth Anniversary Edition. Potomac Books Inc. ISBN 978-1-57488-334-3.

- Gugeler, Russell A. (2005). Combat Actions in Korea. University Press of the Pacific. ISBN 978-1-4102-2451-4.

- Varhola, Michael J. (2000). Fire and Ice: The Korean War, 1950–1953. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-1-882810-44-4.