The Great Gatsby

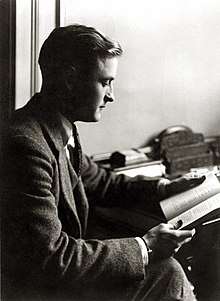

The Great Gatsby is a 1925 novel written by American author F. Scott Fitzgerald that follows a cast of characters living in the fictional towns of West Egg and East Egg on prosperous Long Island in the summer of 1922. Many literary critics consider The Great Gatsby to be one of the greatest novels ever written.[1][2][3][4]

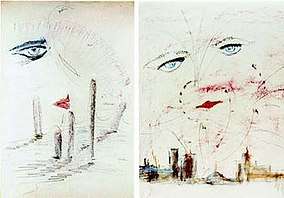

.jpg) First-edition cover illustration | |

| Author | F. Scott Fitzgerald |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Francis Cugat |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Tragedy |

| Published | April 10, 1925 (US) February 10, 1926 (UK) |

| Publisher | Charles Scribner's Sons (US) Chatto & Windus (UK) |

| Media type | Print (hardcover & paperback) |

| Pages | 218 (Original US Edition) |

| Preceded by | The Beautiful and Damned (1922) |

| Followed by | Tender Is the Night (1934) |

The story of the book primarily concerns the young and mysterious millionaire Jay Gatsby and his quixotic passion and obsession to reunite with his ex-lover, the beautiful former debutante Daisy Buchanan. Considered to be Fitzgerald's magnum opus, The Great Gatsby explores themes of decadence, idealism, resistance to change, social upheaval and excess, creating a portrait of the Roaring Twenties that has been described as a cautionary[lower-alpha 1] tale regarding the American Dream.[5][6]

Fitzgerald, inspired by the parties he had attended while visiting Long Island's North Shore, began planning the novel in 1923, desiring to produce, in his words, "something new—something extraordinary and beautiful and simple and intricately patterned."[7] Progress was slow, with Fitzgerald completing his first draft following a move to the French Riviera in 1924.[8] His editor, Maxwell Perkins, felt the book was vague and persuaded the author to revise over the following winter. Fitzgerald was repeatedly ambivalent about the book's title and he considered a variety of alternatives, including titles that referred to the Roman character Trimalchio; the title he was last documented to have desired was Under the Red, White, and Blue.[9]

First published by Scribner's in April 1925, The Great Gatsby received mixed reviews and sold poorly. In its first year, the book sold only 20,000 copies.[10][11] Fitzgerald died in 1940, believing himself to be a failure and his work forgotten.[12] However, the novel experienced a revival during World War II,[13] and became a part of American high school curricula and numerous stage and film adaptations in the following decades.[14] Today, The Great Gatsby is widely considered to be a literary classic and a contender for the title of the "Great American Novel."[15][16]

The novel's U.S. copyright will expire on January 1, 2021, when all works published in 1925 enter the public domain in the United States.[17]

Historical context

Set on the prosperous Long Island of 1922, The Great Gatsby provides a critical social history of Prohibition-era America during the Jazz Age.[lower-alpha 2] That period—known for its jazz music,[19] economic prosperity,[20] flapper culture,[21] libertine mores,[22] rebellious youth,[23] and ubiquitous speakeasies—is fully rendered in Fitzgerald's fictional narrative. Fitzgerald uses many of these 1920s societal developments to tell his story, from simple details such as petting in automobiles[24] to broader themes such as Fitzgerald's discreet allusions to bootlegging as the source of Gatsby's fortune.[25]

Fitzgerald educates his readers about the hedonistic[26] society of the Jazz Age by placing a relatable plotline within the historical context of "the most raucous, gaudy era in U.S. history,"[18] which "raced along under its own power, served by great filling stations full of money."[20][27] In Fitzgerald's eyes, the 1920s era represented a morally permissive time when Americans of all ages became disillusioned with prevailing social norms and were monomaniacally obsessed with self-gratification: "[The Jazz Age represented] a whole race going hedonistic, deciding on pleasure."[26] Hence, The Great Gatsby represents Fitzgerald's attempt to communicate his ambivalent feelings regarding the Jazz Age, an era whose themes he would later regard as reflective of events in his own life.[28]

Various events in Fitzgerald's youth are reflected throughout The Great Gatsby.[29] Fitzgerald was a young Midwesterner from Minnesota, and, like the novel's narrator who went to Yale, he was educated at an Ivy League school, Princeton.[29] While at Princeton, the 19-year-old Fitzgerald met Ginevra King, a 16-year-old socialite with whom he fell in love.[30] However, Ginevra's family discouraged Fitzgerald's pursuit of their daughter due to his lower-class status, and her father purportedly told the young Fitzgerald that "poor boys shouldn't think of marrying rich girls."[31]

Rejected as a suitor due to his lack of financial prospects, Fitzgerald joined the United States Army and was commissioned as a second lieutenant.[29] He was stationed at Camp Sheridan in Montgomery, Alabama where he met Zelda Sayre, a vivacious 17-year-old Southern belle. Zelda agreed to marry him but her parents ended their engagement until he could prove a financial success.[29] Thus Fitzgerald is similar to Jay Gatsby in that he fell in love while a military officer stationed far from home and then sought success to prove himself to the woman he loved.[29]

After his success as a novelist and as a short story writer, Fitzgerald married Zelda and moved to New York. He found his new affluent lifestyle in the exclusive Long Island social milieu to be simultaneously both seductive and repulsive.[29] Fitzgerald—like Gatsby—had always exalted the rich[29] and was driven by his love for a woman who symbolized everything he desired, even as he was led towards a lifestyle which he loathed.[29]

Plot summary

In Spring 1922, Nick Carraway—a Yale alumnus from the Midwest and a veteran of the Great War—journeys east to New York City to obtain employment as a bond salesman. He rents a bungalow in the Long Island village of West Egg, next to a luxurious estate inhabited by Jay Gatsby, an enigmatic multi-millionaire who hosts dazzling soirées yet does not partake in them.

One evening, Nick dines with his distant relative, Daisy Buchanan, in the fashionable town of East Egg. Daisy is married to Tom Buchanan, formerly a Yale football star whom Nick knew during his college days. The couple has recently relocated from Chicago to a colonial mansion directly across the bay from Gatsby's estate. At their mansion, Nick encounters Jordan Baker, an insolent flapper and golf champion who is a childhood friend of Daisy's. Jordan confides to Nick that Tom keeps a mistress, Myrtle Wilson, who brazenly telephones him at his home and who lives in the "valley of ashes," a sprawling refuse dump.[32] That evening, Nick sees Gatsby standing alone on his lawn, staring at a green light across the bay.

Days later, Nick reluctantly accompanies a drunken and agitated Tom to New York City by train. En route, they stop at a garage inhabited by mechanic George Wilson and his wife Myrtle.[33] Myrtle joins them, and the trio proceed to a small New York apartment that Tom has rented for trysts with her. Guests arrive, and a party ensues that ends with Tom slapping Myrtle and breaking her nose after she mentions Daisy.

One morning, Nick receives a formal invitation to a party at Gatsby's mansion. Once there, Nick is embarrassed that he recognizes no one and begins drinking heavily until he encounters Jordan. While chatting with her, he is approached by a man who introduces himself as Jay Gatsby and insists that both he and Nick served in the 3rd Infantry Division during the war. Gatsby attempts to ingratiate himself to Nick and, when Nick leaves the party, he notices Gatsby watching him.

In late July, Nick and Gatsby have lunch at a speakeasy. Gatsby tries to impress Nick with tales of his war heroism and his Oxford days. Afterward, Nick meets Jordan at the Plaza Hotel. She reveals that Gatsby and Daisy met around 1917 when Gatsby was an officer in the American Expeditionary Forces. They fell in love, but when Gatsby was deployed overseas, Daisy reluctantly married Tom. Gatsby hopes that his newfound wealth and dazzling parties will make Daisy reconsider. Gatsby uses Nick to stage a reunion with Daisy, and the two embark upon a sexual affair.

In September, Tom discovers the affair when Daisy carelessly addresses Gatsby with unabashed intimacy in front of him. Later, at a Plaza Hotel suite, Gatsby and Tom argue about the affair. Gatsby insists that Daisy declare that she never loved Tom. Daisy claims she loves Tom and Gatsby, upsetting both. Tom reveals that Gatsby is a swindler whose money comes from bootlegging alcohol. Upon hearing this, Daisy chooses to stay with Tom. Tom scornfully tells Gatsby to drive her home, knowing that Daisy will never leave him.

— F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby[34]

While returning to East Egg, Gatsby and Daisy drive by Wilson's garage and their car accidentally strikes Tom's mistress, Myrtle, killing her instantly. Gatsby reveals to Nick that it was Daisy who was driving the car, but that he intends to take the blame for the accident to protect her. Nick urges Gatsby to flee to avoid prosecution, but he refuses. After Tom tells George that Gatsby owns the car that struck Myrtle, a distraught George assumes the owner of the vehicle must be Myrtle's paramour. George fatally shoots Gatsby in his mansion's swimming pool, then commits suicide.

Several days after Gatsby's murder, his father Henry Gatz arrives for the sparsely-attended funeral. After Gatsby's death, Nick comes to hate New York and decides that Gatsby, Daisy, Tom, and he were all Westerners unsuited to Eastern life. Nick encounters Tom and refuses to shake his hand. Tom admits that he was the one who told George that Gatsby owned the vehicle that killed Myrtle. Before returning to the Midwest, Nick returns to Gatsby's mansion one last time and stares across the bay at the green light emanating from the end of Daisy's dock.

Major characters

- Nick Carraway—a Yale University graduate from the Midwest, a World War I veteran, and, at the start of the plot, a newly arrived resident of West Egg, age 29 (later 30). He also serves as the first-person narrator of the novel. He is Gatsby's next-door neighbor and a bond salesman. He is easy-going, occasionally sarcastic, and somewhat optimistic, although this latter quality fades as the novel progresses. He is more grounded and more practical than the other characters, and is always in awe of their lifestyles and morals.[35]

- Jay Gatsby (originally James "Jimmy" Gatz)—a young, mysterious millionaire with shady business connections (later revealed to be a bootlegger), originally from North Dakota. During World War I, when he was a young military officer stationed at the United States Army's Camp Taylor in Louisville, Kentucky, he encountered the love of his life, the beautiful debutante Daisy Buchanan. Gatsby is also said to have briefly studied at Trinity College, Oxford in England after the end of the war.[36] According to Fitzgerald's wife Zelda, the character was based on the bootlegger and former World War I officer, Max Gerlach.[37]

- Daisy Buchanan—an attractive, though shallow and self-absorbed, young debutante and socialite from Louisville, Kentucky, identified as a flapper.[38] She is Nick's second cousin once removed, and the wife of Tom Buchanan. Before she married Tom, Daisy had a romantic relationship with Gatsby. Her choice between Gatsby and Tom is one of the central conflicts in the novel. The character of Daisy is believed to have been inspired by Fitzgerald's youthful romances with Ginevra King.[39]

- Thomas "Tom" Buchanan—a millionaire who lives in East Egg, and Daisy's husband. Tom is an imposing man of muscular build with a "husky tenor" voice and arrogant demeanor. He was a football star at Yale University. Buchanan has parallels with William Mitchell, the Chicagoan who married Ginevra King.[40] Buchanan and Mitchell were both Chicagoans with an interest in polo. Like Ginevra's father, whom Fitzgerald resented, Buchanan attended Yale and is a white supremacist.[41][42]

- Jordan Baker—an amateur golfer and Daisy Buchanan's long-time friend with a sarcastic streak and an aloof attitude. She is Nick Carraway's girlfriend for most of the novel, though they grow apart towards the end. She has a slightly shady reputation because of rumors that she had cheated in a tournament, which harmed her reputation socially and as a golfer. Fitzgerald told Maxwell Perkins that Jordan was based on the golfer Edith Cummings, a friend of Ginevra King, though Cummings was never suspected of cheating.[43] Her name is a play on the two popular automobile brands, the Jordan Motor Car Company and the Baker Motor Vehicle, both of Cleveland, Ohio,[44] alluding to Jordan's "fast" reputation and the new freedom presented to Americans, especially women, in the 1920s.[45][46][47]

- George B. Wilson—a mechanic and owner of a garage. He is disliked by both his wife, Myrtle Wilson and Tom Buchanan, who describes him as "so dumb he doesn't know he's alive." At the end of the novel, he kills Gatsby, wrongly believing that he had been driving the car that killed Myrtle, and then kills himself.

- Myrtle Wilson—George's wife, and Tom Buchanan's mistress. Myrtle, who possesses a fierce vitality, is desperate to find refuge from her disappointing marriage. She is accidentally killed by Gatsby's car, as she thinks it is Tom still driving and runs after it (driven by Daisy, though Gatsby takes the blame for the accident).

- Meyer Wolfsheim[lower-alpha 3]—a Jewish friend and mentor of Gatsby's, described as a gambler who fixed the 1919 World Series. Wolfsheim appears only twice in the novel, the second time refusing to attend Gatsby's funeral. He is a clear allusion to Arnold Rothstein,[50] a New York crime kingpin who was notoriously blamed for the Black Sox Scandal that tainted the 1919 World Series.[51]

Writing and production

Fitzgerald began planning his third novel in June 1922,[25] but it was interrupted by the production of his play, The Vegetable, in the summer and fall.[52] The play failed miserably, and Fitzgerald worked that winter on magazine stories struggling to pay his debt caused by the production.[53][54] The stories were, in his words, "all trash and it nearly broke my heart,"[54] although included among those stories was "Winter Dreams," which Fitzgerald later described as "a sort of first draft of the Gatsby idea."[55]

After the birth of their only child, Frances Scott "Scottie" Fitzgerald, the Fitzgeralds moved in October 1922 to Great Neck, New York, on Long Island. The town was used as the scene of The Great Gatsby.[56] Fitzgerald's neighbors in Great Neck included such prominent and newly wealthy New Yorkers as writer Ring Lardner, actor Lew Fields, and comedian Ed Wynn.[25] These figures were all considered to be "new money," unlike those who came from Manhasset Neck or Cow Neck Peninsula—places that were home to many of New York's wealthiest established families, and which sat across the bay from Great Neck.

This real-life juxtaposition gave Fitzgerald his idea for "West Egg" and "East Egg." In this novel, Great Neck (Kings Point) became the "new money" peninsula of West Egg and Port Washington (Sands Point) became the "old money" East Egg.[57] Several mansions in the area served as inspiration for Gatsby's home, such as Oheka Castle[58] and Beacon Towers, since demolished.[59] (Another possible inspiration was Land's End, a notable Gold Coast Mansion where Fitzgerald may have attended a party.[60])

While the Fitzgeralds were living in New York, the Hall-Mills murder case was sensationalized in the daily newspapers over the course of many months, and the highly publicized case likely influenced the plot of Fitzgerald's novel.[61][62] The case involved the double-murder of a man and his lover which occurred on September 14, 1922, mere weeks before Fitzgerald and his wife arrived in Great Neck. Scholars have speculated that Fitzgerald based certain aspects of the ending of The Great Gatsby as well as various characterizations on this factual incident.[63]

By mid-1923, Fitzgerald had written 18,000 words for his novel,[64] but discarded most of his new story as a false start. Some of it, however, resurfaced in the 1924 short story "Absolution."[25][65][66] Work on The Great Gatsby began in earnest in April 1924. Fitzgerald wrote in his ledger, "Out of woods at last and starting novel."[54] He decided to make a departure from the writing process of his previous novels and told Perkins that the novel was to be a "consciously artistic achievement"[67] and a "purely creative work—not trashy imaginings as in my stories but the sustained imagination of a sincere and yet radiant world."[68][69] Soon after this burst of inspiration, work slowed while the Fitzgeralds made a move to the French Riviera, where a serious crisis[lower-alpha 4] in their relationship soon developed.[54]

By August, however, Fitzgerald was hard at work and completed what he believed to be his final manuscript in October, sending the book to his editor, Maxwell Perkins, and agent, Harold Ober, on October 30.[54] The Fitzgeralds then moved to Rome for the winter.[70] Fitzgerald made revisions through the winter after Perkins informed him in a November letter that the character of Gatsby was "somewhat vague" and Gatsby's wealth and business, respectively, needed "the suggestion of an explanation" and should be "adumbrated."[71] Fitzgerald thanked Perkins for his detailed criticisms and stated, "With the aid you've given me I can make Gatsby perfect."[72]

Content after a few rounds of revision, Fitzgerald returned the final batch of revised galleys in the middle of February 1925.[73] Fitzgerald's revisions included an extensive rewriting of Chapter VI and VIII.[54] Further, he refused $10,000 for the serial rights to the book so that it could be published sooner.[54] He had received a $3,939 advance in 1923[74] and $1,981.25 upon publication.[75]

Cover art

Unlike Gatsby and Tom Buchanan, I had no girl whose disembodied face floated along the dark cornices and blinding signs...[76]

The cover of the first printing of The Great Gatsby is among the most celebrated pieces of art in American literature.[76] It depicts disembodied eyes and a mouth over a blue skyline, with images of naked women reflected in the irises. A little-known artist named Francis Cugat was commissioned to illustrate the book while Fitzgerald was in the midst of writing it.[76]

The cover was completed before the novel, and Fitzgerald was so enamored with it that he told his publisher he had "written it into" the novel.[77] Fitzgerald's remarks about incorporating the painting into the novel led to the interpretation that the eyes are reminiscent of those of fictional optometrist Dr. T. J. Eckleburg,[78] depicted on a faded commercial billboard near George Wilson's auto repair shop, which Fitzgerald described as:

"blue and gigantic—their retinas[lower-alpha 5] are one yard high. They look out of no face, but instead, from a pair of enormous yellow spectacles which pass over a non-existent nose."

Although this passage has some resemblance to the painting, a closer explanation can be found in the description of Daisy Buchanan as the "girl whose disembodied face floated along the dark cornices and blinding signs."[76] Years later, Ernest Hemingway wrote in A Moveable Feast that when Fitzgerald lent him a copy of The Great Gatsby to read, he immediately disliked the cover, but "Scott told me not to be put off by it, that it had to do with a billboard along a highway in Long Island that was important in the story. He said he had liked the jacket and now he didn't like it."[79]

Alternative titles

Fitzgerald had difficulty choosing a title for his novel and entertained many choices before reluctantly choosing The Great Gatsby,[80] a title inspired by Alain-Fournier's Le Grand Meaulnes.[81] Previously he had shifted between Gatsby, Among Ash-Heaps and Millionaires, Trimalchio,[9] Trimalchio in West Egg,[82] On the Road to West Egg,[83] Under the Red, White, and Blue,[9] The Gold-Hatted Gatsby,[9][83] and The High-Bouncing Lover.[9][83] The titles The Gold-Hatted Gatsby and The High-Bouncing Lover came from Fitzgerald's epigraph for the novel, one which he wrote himself under the pen name of Thomas Parke D'Invilliers.[84] He initially preferred titles referencing Trimalchio, the crude parvenu in Petronius's Satyricon, and even refers to Gatsby as Trimalchio once in the novel:

"It was when curiosity about Gatsby was at its highest that the lights in his house failed to go on one Saturday night—and, as obscurely as it had begun, his career as Trimalchio was over."[85]

Unlike Gatsby's spectacular parties, Trimalchio participated in the audacious and libidinous orgies he hosted but, according to Tony Tanner's introduction to the Penguin edition, there are subtle similarities between the two.[86]

In November 1924, Fitzgerald wrote to Perkins that "I have now decided to stick to the title I put on the book ... Trimalchio in West Egg,"[87] but was eventually persuaded that the reference was too obscure and that people would not be able to pronounce it.[88] His wife, Zelda, and Perkins both expressed their preference for The Great Gatsby and the next month Fitzgerald agreed.[89] A month before publication, after a final review of the proofs, he asked if it would be possible to re-title it Trimalchio or Gold-Hatted Gatsby but Perkins advised against it. On March 19, 1925,[90] Fitzgerald expressed intense enthusiasm for the title Under the Red, White, and Blue, but it was at that stage too late to change.[91][92] The Great Gatsby was published on April 10, 1925.[93] Fitzgerald remarked that "the title is only fair, rather bad than good."[94]

Early drafts of the novel have been published under the title Trimalchio: An Early Version of The Great Gatsby.[95][96] A notable difference between the Trimalchio draft and The Great Gatsby is a less complete failure of Gatsby's dream in Trimalchio. Another difference is that the argument between Tom Buchanan and Gatsby is more even,[97] although Daisy still returns to Tom.

Contemporary reception

The Great Gatsby was published by Charles Scribner's Sons on April 10, 1925. Fitzgerald called Perkins on the day of publication to monitor reviews: "Any news?"[54] "Sales situation doubtful," read a wire from Perkins on April 20, "[but] excellent reviews." Fitzgerald responded on April 24, saying the cable "depressed" him, closing the letter with "Yours in great depression."[11] Fitzgerald had hoped the novel would be a great commercial success, perhaps selling as many as 75,000 copies.[11] The book had sold fewer than 20,000 copies by the time the original sale was done in October.[10][11] Despite this, Scribner's kept the original edition of the book on their trade list until 1946. At that time, three other forms of Gatsby were in print, so there was no longer any point to holding onto the original edition.[54] Fitzgerald received letters of praise from contemporaries T. S. Eliot, Edith Wharton, and Willa Cather regarding the novel; however, this was private opinion, and Fitzgerald feverishly sought the public recognition of reviewers and readers.[54]

The Great Gatsby received mixed reviews from literary critics of the day. Generally the most effusive of the positive reviews was Edwin Clark of The New York Times, who felt the novel was "A curious book, a mystical, glamourous story of today."[98] Similarly, Lillian C. Ford of the Los Angeles Times wrote, "[the novel] leaves the reader in a mood of chastened wonder," calling the book "a revelation of life" and "a work of art."[99] The New York Post called the book "fascinating ... His style fairly scintillates, and with a genuine brilliance; he writes surely and soundly."[100] The New York Herald Tribune was less impressed, referring to The Great Gatsby as "purely ephemeral phenomenon, but it contains some of the nicest little touches of contemporary observation you could imagine—so light, so delicate, so sharp ... a literary lemon meringue."[101] In The Chicago Daily Tribune, H. L. Mencken called the book "in form no more than a glorified anecdote, and not too probable at that," while praising the book's "charm and beauty of the writing" and the "careful and brilliant finish."[102]

— H. L. Mencken, Chicago Tribune, May 1925[103]

Several writers felt that the novel left much to be desired following Fitzgerald's previous works and promptly criticized him. Harvey Eagleton of The Dallas Morning News believed the novel signaled the end of Fitzgerald's success: "One finishes Great Gatsby with a feeling of regret, not for the fate of the people in the book, but for Mr. Fitzgerald."[104] John McClure of The Times-Picayune said that the book was unconvincing, writing, "Even in conception and construction, The Great Gatsby seems a little raw."[105] Ralph Coghlan of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch felt the book lacked what made Fitzgerald's earlier novels endearing and called the book "a minor performance ... At the moment, its author seems a bit bored and tired and cynical."[106] Ruth Snyder of New York Evening World called the book's style "painfully forced," noting that the editors of the paper were "quite convinced after reading The Great Gatsby that Mr. Fitzgerald is not one of the great American writers of to-day."[107] The reviews struck Fitzgerald as completely missing the point: "All the reviews, even the most enthusiastic, not one had the slightest idea what the book was about."[65]

Fitzgerald's goal was to produce a literary work which would truly prove himself as a writer,[108] and Gatsby did not have the commercial success of his two previous novels, This Side of Paradise and The Beautiful and Damned. Although the novel went through two initial printings, some of these copies remained unsold years later.[109] Fitzgerald himself blamed poor sales on the fact that women tended to be the main audience for novels during this time, and Gatsby did not contain an admirable female character.[109] According to his own ledger, now made available online by University of South Carolina's Thomas Cooper Library, he earned only $2,000 from the book.[8][74] Although 1926 brought Owen Davis' stage adaption and the Paramount-issued silent film version, both of which brought in money for the author, Fitzgerald still felt the novel fell short of the recognition he hoped for and, most importantly, would not propel him to becoming a serious novelist in the public eye.[54] For several years afterward, the general public believed The Great Gatsby to be nothing more than a nostalgic period piece.[54] By the time Fitzgerald died in 1940, the novel had fallen into near obscurity.[110]

Revival and reassessment

In 1940, Fitzgerald suffered a third and fatal heart attack, and died believing his work forgotten.[111] His obituary in The New York Times mentioned Gatsby as Fitzgerald "at his best."[112] A strong appreciation for the book gradually developed in underground circles. Future writers Edward Newhouse and Budd Schulberg were deeply affected by it, and author John O'Hara acknowledged its influence.[113] Thus, by the time that Gatsby was republished in Edmund Wilson's edition of The Last Tycoon in 1941, the general consensus was that the book was an enduring work of fiction.[54]

In 1942, a group of publishing executives created the Council on Books in Wartime. The council's purpose was to distribute paperback Armed Services Editions books to soldiers fighting in the Second World War. The Great Gatsby was one of these books. The books proved to be "as popular as pin-up girls" among the soldiers, according to the Saturday Evening Post's contemporary report.[114] 155,000 copies of Gatsby were distributed to soldiers overseas.[115]

By 1944, full-length articles on Fitzgerald's works were being published, and the following year, "the opinion that Gatsby was merely a period piece had almost entirely disappeared."[54] This revival was paved by interest shown by literary critic Edmund Wilson, who was Fitzgerald's friend.[116] In 1951, Arthur Mizener published The Far Side of Paradise, a biography of Fitzgerald.[117] He emphasized The Great Gatsby's positive reception by literary critics, which may have influenced public opinion and renewed interest in it.[118]

By 1960, the book was steadily selling 50,000 copies per year, and renewed interest led The New York Times editorialist Mizener to proclaim the novel "a classic of twentieth-century American fiction."[54] The Great Gatsby has sold over 25 million copies worldwide as of 2013, annually sells an additional 500,000 copies and is Scribner's most popular title; in 2013, the e-book alone sold 185,000 copies.[12]

Critical analysis

Themes

American Dream

Following the novel's revival, later critical writings on The Great Gatsby focus in particular on Fitzgerald's disillusionment with the American dream[lower-alpha 1] in the context of the hedonistic Jazz Age,[lower-alpha 2] a name for the era which Fitzgerald claimed to have coined.[119] In 1970, scholar Roger L. Pearson published an essay in which he asserted that Fitzgerald "has come to be associated with this concept of the American dream more than any other writer of the twentieth century."[120] Pearson traced the literary origins of this particular dream to Colonial America:

"The American dream, or myth, is an ever recurring theme in American literature, dating back to some of the earliest colonial writings. Briefly defined, it is the belief that every man, whatever his origins, may pursue and attain his chosen goals, be they political, monetary, or social. It is the literary expression of the concept of America: The land of opportunity."[120]

However, Pearson noted that "Fitzgerald's unique expression of the American dream lacks the optimism, the sense of fulfillment, so evident in the expressions of his predecessors."[120] He posited that Fitzgerald created the character of Gatsby to serve as a false prophet of the American dream and to demonstrate how that dream no longer exists except in the minds of those as materialistic as Gatsby.[121] Pearson concluded that the American dream pursued by Gatsby "is, in reality, a nightmare," bringing nothing but discontent and disillusionment to those who chase it as they realize that it is unsustainable and ultimately unattainable.[121]

Echoing Pearson's interpretation, scholar Sarah Churchwell similarly views The Great Gatsby to be a "cautionary tale of the decadent downside of the American dream."[122] Churchwell posits the story concerns the limits of America's ideals of social and class mobility, and the hopelessness of lower-class aspirants to transcend the stations of their birth.[122] This is illustrated through the novel's narrator, Nick Carraway, who observes that "a sense of the fundamental decencies is parcelled out unequally at birth."[123] Churchwell posits that Fitzgerald's novel is "a story of class warfare in a nation that denies it even has a class system, in which the game is eternally rigged for the rich to win."[122]

The green light that shines at the end of the dock of Daisy's house across the Sound from Gatsby's house is frequently mentioned in the background of the plot. It has variously been interpreted as a symbol of Gatsby's longing for Daisy and, more broadly, of the American dream.[110]

Gender relations

In addition to exploring the trials and tribulations of achieving the American dream during the Jazz Age, The Great Gatsby explores societal gender expectations as a theme. Although early scholars viewed the character of Daisy Buchanan to be a "monster of bitchery,"[124] later scholars such as Leland S. Person, Jr. asserted that Daisy's character exemplifies the marginalization of women in the East Egg social milieu that Fitzgerald depicts.[125][126] Writing in 1978, Person noted that:

"Daisy, in fact, is more victim than victimizer: She is a victim first of Tom Buchanan's 'cruel' power, but then of Gatsby's increasingly depersonalized vision of her. She becomes the unwitting 'grail' in Gatsby's adolescent quest to remain ever-faithful to his seventeen-year-old conception of self."[127]

Daisy is thus "reduced to a golden statue, a collector's item which crowns Gatsby's material success."[128] As an upper-class white woman living in East Egg during this time period, Daisy must adhere to societal expectations and gender norms such as actively fulfilling the roles of dutiful wife, mother, keeper of the house, and charming socialite.[125] Many of Daisy's choices—ultimately culminating in the tragedy of the ending and misery for all those involved—can be partly attributed to her prescribed role as a "beautiful little fool"[lower-alpha 6] who is reliant on her husband for financial and societal security.[124] Her decision to remain with her husband despite her feelings for Gatsby is thus attributable to the status, security, and comfort that her marriage to Tom Buchanan provides.[124]

Class inequality

Journalist Nick Gillespie interprets The Great Gatsby as a story of the underlying permanence of class differences, even "in the face of a modern economy based not on status and inherited position but on innovation and an ability to meet ever-changing consumer needs."[130] This interpretation asserts that The Great Gatsby captures the American experience because it is a story about change and those who resist it, whether the change comes in the form of a new wave of immigrants or the nouveau riche or successful minorities.[130] Americans living in the 1920s to the present are thus defined by their fluctuating economic and social circumstances. As Gillespie states, "While the specific terms of the equation are always changing, it's easy to see echoes of Gatsby's basic conflict between established sources of economic and cultural power and upstarts in virtually all aspects of American society."[130] Because this can be seen throughout American history, readers are able to relate to The Great Gatsby, which has contributed to the novel's enduring popularity.[130]

Other interpretations

Environmental criticism of Gatsby seeks to place the novel and its characters in historical context almost a century after its original publication. These interpretations argue that Jay Gatsby and The Great Gatsby can be viewed as the personification and representation of human-caused climate change, as "Gatsby's life depends on many human-centered, selfish endeavors" which are "in some part responsible for Earth's current ecological crisis."[131]

Controversy

Like many of Fitzgerald's works, The Great Gatsby has been accused of displaying anti-Semitism through the use of Jewish stereotypes.[132] The book describes Meyer Wolfsheim[lower-alpha 3] as "a small, flat-nosed Jew", with "tiny eyes" and "two fine growths of hair" in his nostrils, while his nose is described as "expressive", "tragic", and able to "flash... indignantly".[133] A dishonest and corrupt profiteer who assisted Gatsby's bootlegging operations and manipulated the World Series, Wolfsheim has also been seen as representing the Jewish miser stereotype. Richard Levy, author of Antisemitism: A Historical Encyclopedia of Prejudice and Persecution, claims that Wolfsheim is "pointedly connected Jewishness and crookedness".[133]

In a 1947 article for Commentary, Milton Hindus, an assistant professor of humanities at the University of Chicago, stated that while he believed the book was "excellent" on balance, Wolfsheim "is easily its most obnoxious character", and "the novel reads very much like an anti-Semitic document". Hindus argued that the Jewish stereotypes displayed by Wolfsheim were typical of the time period in which the novel was written and set and that its anti-Semitism was of the "habitual, customary, 'harmless,' unpolitical variety."[133]

A 2015 article by Arthur Krystal agreed with Hindus's assessment that Fitzgerald's use of Jewish caricatures was not driven by malice and merely reflected commonly-held beliefs of his time. He notes the accounts of Frances Kroll, a Jewish woman and secretary to Fitzgerald, who claimed that Fitzgerald was hurt by accusations of anti-Semitism and responded to critiques of Wolfsheim by claiming that he merely "fulfilled a function in the story and had nothing to do with race or religion".[132] This claim is further supported by evidence that Wolfsheim was based on real-life Jewish gambler Arnold Rothstein.[132][51]

Adaptations

_-_I_Romanzi_della_Palma_Mondadori_1936.jpg)

Ballet

- In 2009, BalletMet premiered a version at the Capitol Theatre in Columbus, Ohio. It was choreographed by Jimmy Orrante.[134]

- In 2010, The Washington Ballet premiered a version at the Kennedy Center.[135] It was received an encore run the following year.[136]

- In 2013, the Northern Ballet premiered a version of The Great Gatsby at Leeds Grand Theatre in the UK, with choreography and direction by David Nixon, a musical score by Richard Rodney Bennett, and set designs by Jerome Kaplan. Nixon also created the scenario and costume designs.[137][138]

Computer games

- In 2010, Oberon Media released a casual hidden object game called Classic Adventures: The Great Gatsby.[139][140] The game was released for iPad in 2012.[141]

- In 2011, as a tribute to old NES games, developer Charlie Hoey and editor Pete Smith created an 8-bit-style online game of The Great Gatsby called The Great Gatsby for NES.[142] Ian Crouch of The New Yorker compared it to The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1989) for the NES.[143]

- In 2013, Slate (magazine) released a short symbolic adaptation called "The Great Gatsby: The Video Game".[144]

Film

The Great Gatsby has been adapted to film a number of times:

- The Great Gatsby (1926), directed by Herbert Brenon—starring Warner Baxter, Lois Wilson, and William Powell, a lost film.[lower-alpha 7][146]

- The Great Gatsby (1949), directed by Elliott Nugent—starring Alan Ladd, Betty Field, and Macdonald Carey.[145][146]

- The Great Gatsby (1974), directed by Jack Clayton—starring Robert Redford, Mia Farrow, and Sam Waterston.[145][146]

- The Great Gatsby (2013), directed by Baz Luhrmann—starring Leonardo DiCaprio, Carey Mulligan, and Tobey Maguire.[8][146]

Literature

- The Double Bind (2007) by Chris Bohjalian imagines the later years of Daisy and Tom Buchanan's marriage, as a social worker in 2007 investigates the possibility that a deceased elderly homeless person is Daisy's son.[147]

- Great (2014) by Sara Benincasa is a modern-day young adult fiction retelling of The Great Gatsby with a female Gatsby named Jacinta Trimalchio.[148]

Opera

- The New York Metropolitan Opera commissioned John Harbison to compose an operatic treatment of the novel to commemorate the 25th anniversary of James Levine's debut. The work, called The Great Gatsby, premiered on December 20, 1999.[149]

Radio

- On January 1, 1950, an hour-long adaptation was broadcast on CBS's Family Hour of Stars starring Kirk Douglas as Gatsby.[150]

- In October 2008, the BBC World Service commissioned an abridged 10-part reading of the story, read from the view of Nick Carraway by Trevor White.[151]

- In May 2012, BBC Radio 4 broadcast The Great Gatsby, a Classic Serial dramatization by Robert Forrest.[152]

Television

The Great Gatsby has been adapted several times as television films and as episodes for various dramatic series:

- The Great Gatsby (1955), by Alvin Sapinsley—a NBC episode for Robert Montgomery Presents starring Robert Montgomery, Phyllis Kirk, and Lee Bowman.[153]

- The Great Gatsby (1958), by Franklin J. Schaffner—a CBS episode for Playhouse 90 starring Robert Ryan, Jeanne Crain, and Rod Taylor.[146]

- The Great Gatsby (2000), by Robert Markowitz—an A&E movie starring Toby Stephens, Mira Sorvino, and Paul Rudd.[8][146]

Theater

- The 1926 stage adaptation of Owen Davis,[154] subsequently developed, became the 1926 film version. The play, directed by George Cukor, opened on Broadway on February 2, 1926, and ran for 112 performances. A successful tour later in the year included performances in Chicago, 1 August 20 through 2 October.[155]

- In July 2006, Simon Levy's stage adaptation,[156] the only one authorized and granted exclusive rights by the Fitzgerald estate, premiered at The Guthrie Theater to commemorate the opening of its new theatre, directed by David Esbjornson. It was subsequently produced by Seattle Repertory Theatre. In 2012, a revised version was produced at Arizona Theatre Company[157] and Grand Theatre in London, Ontario, Canada.[156]

- In 2010, Gatz, an Off-Broadway production by Elevator Repair Service, debuted and was highly praised by critic Ben Brantley of The New York Times.[158]

See also

References

Notes

- "[The Great Gatsby] is the Great American Dream," says Jeff Nilsson, historian for the bimonthly The Saturday Evening Post. "It is the story that if you work hard enough, you can succeed. Yet Gatsby also explores the dream's destructive power. Americans pay a great price for that dream."[18]

- "Fitzgerald was the poet laureate of what he named 'The Jazz Age,' the most raucous, gaudy era in U.S. history. 'The 1920s is the most fascinating era in American culture,' says [historian] Nilsson. 'Everything was changing so much.' Youth in revolt didn't start at Woodstock, it began with Gertrude Stein's Lost Generation."[18]

- The spelling "Wolfshiem" appears throughout Fitzgerald's original manuscript, while "Wolfsheim" was introduced by editor Edmund Wilson in the second edition[48] and appears in later Scribner's editions.[49]

- In France, while Fitzgerald was writing the novel near Cannes, his wife Zelda was allegedly romanced by a French officer and "romping around pretty much where the Palais des Festivals is."[8]

- The original edition used the anatomically incorrect word 'retinas,' while some later editions have used the word 'irises.'

- Daisy's declaration that she hopes her daughter will be a "beautiful little fool" was first spoken by Fitzgerald's wife Zelda when their child Scottie was born on October 26, 1921, in a St. Paul hospital.[129]

- The 1926 silent film is based upon the stage adaptation. It is a famous example of a lost film. Reviews suggest that it may have been the most faithful adaptation of the novel, but a trailer of the film at the National Archives is all that is known to exist.[145] Reportedly, Fitzgerald and his wife Zelda loathed the silent version. "We saw The Great Gatsby at the movies," Zelda wrote to an acquaintance. "It's rotten and awful and terrible and we left."[8]

Citations

- "12 Novels Considered the "Greatest Book Ever Written"". Encyclopaedia Britannica.

- "All-TIME 100 Novels". TIME.

- Burt, Daniel S. (2010). The Novel 100: A Ranking of the Greatest Novels of All Time. Checkmark Books.

- "The Greatest Books". thegreatestbooks.org.

- Karolides, Bald & Sova 2011, p. 499: "Rather than a celebration of such decadence, the novel functions as a cautionary tale in which an unhappy fate is inevitable for the poor and striving individual, and the rich are allowed to continue without penalty their careless treatment of others' lives."

- Hoover 2013: "What sank the novel in 1925 is the source of its success today. The Great Gatsby challenges the myth of the American Dream, glowing like the green light on Daisy's dock in the Roaring '20s."

- Letter to Maxwell Perkins, July 1922: "I want to write something new—something extraordinary and beautiful and simple & intricately patterned."

- Howell 2013.

- Andersen 2010.

- Symkus 2013.

- O'Meara 2002.

- Gatsby By The Numbers.

- Cole 1984, p. 28.

- Donahue 2013: "Fitzgerald scholar James L. W. West III says it is no coincidence that The Great Gatsby is probably the American novel most often taught in the rest of the world. 'It is our novel, how we present ourselves. ... He captured and distilled the essence of the American spirit.'"

- Eble 1974, pp. 34, 45.

- Batchelor 2013.

- Alter 2018: "In anticipation of a flood of new editions of Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby when the copyright expires in 2021, the Fitzgerald estate and his publisher, Scribner, released a new edition of the novel in April, hoping to position it as the definitive version of the text."

- Donahue 2013.

- Fitzgerald 2003, p. 16: "The word jazz in its progress toward respectability has meant first sex, then dancing, then music. It is associated with a state of nervous stimulation, not unlike that of big cities behind the lines of a war."

- Fitzgerald 2003, p. 18: "In any case, the Jazz Age now raced along under its own power, served by great filling stations full of money."

- Fitzgerald 2003, p. 15: "Scarcely had the staider citizens of the republic caught their breaths when the wildest of all generations, the generation which had been adolescent during the confusion of the [Great] War, brusquely shouldered my contemporaries out of the way and danced into the limelight. This was the generation whose girls dramatized themselves as flappers, the generation that corrupted its elders and eventually overreached itself less through lack of morals than through lack of taste."

- Fitzgerald 2003, p. 18: "The less sought-after girls who had become resigned to sublimating probable celibacy, came across Freud and Jung in seeking their intellectual recompense and came tearing back into the fray. By 1926 the universal preoccupation with sex had become a nuisance."

- Donahue 2013: "Youth in revolt didn't start at Woodstock, it began with Gertrude Stein's Lost Generation."

- Fitzgerald 2003, pp. 14–15: "As far back as 1915 the unchaperoned young people of the smaller cities had discovered the mobile privacy of that automobile given to young Bill at sixteen to make him 'self-reliant'. At first petting was a desperate adventure even under such favorable conditions, but presently confidences were exchanged and the old commandment broke down."

- Bruccoli 2000, pp. 53–54.

- Fitzgerald 2003, p. 15: "[The Jazz Age represented] a whole race going hedonistic, deciding on pleasure."

- Gross 1998, p. 167: "Like all great books, [The Great Gatsby] rises above its historical context. Although knowledge of the background adds dimension to the novel, it can stand very well without it. The garish, frenetic world of the 1920s is gone."

- Fitzgerald 2003, pp. 13–24: Fitzgerald documented the Jazz Age and his own life's relation to the era in his essay, "Echoes of the Jazz Age" which was later published in the essay collection The Crack-Up.

- SparkNotes: The Great Gatsby.

- Smith 2003: Fitzgerald later confided to his daughter that Ginevra King "was the first girl I ever loved" and that he "faithfully avoided seeing her" in order to "keep the illusion perfect."

- Smith 2003.

- Holowka 2009: "The valley of ashes was based on the sprawling Corona dump which would be regraded and buried under the 1939 World's Fair site, now Corona Flushing Meadows Park."

- ArchiTakes, architecture in New York and beyond, December 17th, 2009. The Iron Triangle / Wilson’s Garage.

- Fitzgerald 2006, p. 113.

- Eble 1974, p. 40.

- McCullen 2007, pp. 11–20.

- Bruccoli 2002, p. 178: "Jay Gatsby was inspired in part by a local figure, Max Gerlach. Near the end of her life Zelda Fitzgerald said that Gatsby was based on 'a neighbor named Von Guerlach or something who was said to be General Pershing's nephew and was in trouble over bootlegging.'"

- Conor 2004, p. 301: "Fitzgerald's literary creation Daisy Buchanan in The Great Gatsby was identified with the type of the flapper. Her pictorial counterpart was drawn by the American cartoonist John Held, Jr., whose images of party-going flappers who petted in cars frequented the cover of the American magazine Life during the 1920s."

- Borrelli 2013.

- Bruccoli 2002, p. 86.

- Bruccoli 2000, pp. 9–11, 246.

- Baker 2016.

- Bruccoli 2000, pp. 9–11.

- Whipple 2019, p. 85.

- Fitzgerald 1991, p. 184. Editor Matthew J. Bruccoli notes: "This name combines two automobile makes: The sporty Jordan and the conservative Baker electric."

- Fitzgerald 2006, p. 95.

- Tredell 2007, p. 124: An index note refers to Laurence E. MacPhee's "The Great Gatsby's Romance of Motoring: Nick Carraway and Jordan Baker," Modern Fiction Studies, 18 (Summer 1972), pp. 207–12.

- Fitzgerald 1991, p. liv.

- Fitzgerald 1991, p. 148.

- Bruccoli 2002, p. 179: "Meyer Wolfshiem, 'the man who fixed the World Series back in 1919,' was obviously based on gambler Arnold Rothstein, whom Fitzgerald had met in unknown circumstances."

- Bruccoli 2000, p. 29.

- Mizener 1960: "He had begun to plan the novel in June 1923, saying to Maxwell Perkins, 'I want to write something new — something extraordinary and beautiful and simple and intricately patterned.' But that summer and fall were devoted to the production of his play, 'The Vegetable.'"

- Curnutt 2004, p. 58: "The failure of The Vegetable in the fall of 1923 caused Fitzgerald, who was by then in considerable debt, to shut himself in a stuffy room over a garage in Great Neck, New York, and write himself out of the red by turning out ten short stories for the magazine market."

- Mizener 1960.

- Fitzgerald 1963, p. 189: "3. 'Winter Dreams' (a sort of first draft of the Gatsby idea from Metropolitan 1923)

- Murphy 2010: "Fitzgerald himself knew [Great Neck] well. He and Zelda lived at 6 Gateway Drive in Great Neck, N.Y., on the Port Washington line, from October 1922 to April 1924. He seeded his masterpiece there, drawing on his own experiences on 'that slender riotous island,' and in a room above the garage turning out short stories that prefigured Gatsby."

- Bruccoli 2000, pp. 38–39.

- Bruccoli 2000, p. 45.

- Randall 2003, pp. 275–277.

- Kellogg 2011: "The 1902 home was owned, during its jazz-age heyday, by journalist Herbert Bayard Swope, one of the first recipients of the Pulitzer Prize and editor of the New York World. F. Scott Fitzgerald was said to have attended Swope's parties; the house, in Sands Point, New York, was the model for Daisy Buchanan's place."

- Lopate 2014: Interview with Sarah Churchwell.

- Churchwell 2013, pp. 1–9.

- Powers 2013, pp. 9–11: "The Hall-Mills murder case unfolded in the newspapers over many months: The double killing of an Episcopal minister and his lover occurred on the night of 14 September 1922, a few days before Fitzgerald and his wife arrived in New York."

- West 2002, p. xi: "He produces 18,000 words; most of this material is later discarded, but he salvages the short story 'Absolution,' published in June 1924."

- Eble 1974, p. 37.

- Haglund 2013: "The short story 'Absolution,' first published in the American Mercury in 1924 and included in Fitzgerald's 1926 collection All the Sad Young Men, was, according to the author, 'intended to be a picture of [Gatsby's] early life,' but he 'cut it because I preferred to preserve the sense of mystery.'"

- Eble 1974, p. 37. Fitzgerald wrote to Perkins: "I feel I have enormous power in me now. This book will be a consciously artistic achievement and must depend on that as the first books did not."

- Flanagan 2000: "He may have been remembering Fitzgerald's words in that April letter: 'So in my new novel I'm thrown directly on purely creative work—not trashy imaginings as in my stories but the sustained imagination of a sincere yet radiant world.' He added later, during editing, that he felt 'an enormous power in me now, more than I've ever had.'"

- Leader 2000, pp. 13–15.

- Tate 2007, p. 326: "They lived in ROME from October 1924 to February 1925..."

- Perkins 2004, pp. 27–30.

- Eble 1974, p. 38.

- Bruccoli 2000, pp. 54–56.

- F. Scott Fitzgerald's ledger 1919-1938.

- Zuckerman 2013.

- Scribner 1992, pp. 140–155.

- Scribner 1992, pp. 140–155. Fitzgerald wrote to Perkins: "For Christ's sake don't give anyone that jacket you're saving for me. I've written it into the book."

- Scribner 1992, pp. 140–155: "We are left then with the enticing possibility that Fitzgerald's arresting image was originally prompted by Cugat's fantastic apparitions over the valley of ashes; in other words, that the author derived his inventive metamorphosis from a recurrent theme of Cugat's trial jackets, one which the artist himself was to reinterpret and transform through subsequent drafts."

- Hemingway 1964, p. 176: "A day or two after the trip Scott brought his book over. It had a garish dust jacket and I remember being embarrassed by the violence, bad taste, and slippery look of it. It looked like the book jacket for a book of bad science fiction. Scot told me not to be put off by it, that it had to do with a billboard along a highway in Long Island that was important in the story. He said he had liked the jacket and now he didn't like it. I took it off to read the book."

- Andersen 2010: Donald Skemer states: "[Fitzgerald] went through many, many titles including Under the Red, White, and Blue and Trimalchio and Gold-hatted Gatsby." James West also lists other titles such as "The High Bouncing Lover" and adds that "in the end [Fitzgerald] didn't think that The Great Gatsby was a very good title."

- The Economist 2012: "Fitzgerald borrowed its title for The Great Gatsby (and some critics think Fournier's main characters were models for Nick Carraway, Fitzgerald's narrator, and his lovelorn pal)."

- Vanderbilt 1999, p. 96: "A week later, in his next letter, he was floundering: 'I have not decided to stick to the title I put on the book, Trimalchio in West Egg. The only other titles that seem to fit it are Trimalchio and On the Road to West Egg. I had two others, Gold-hatted Gatsby and The High-bouncing Lover, but they seemed too slight.'"

- Vanderbilt 1999, p. 96.

- Wulick 2018.

- Fitzgerald 1991, p. 88, Chapter 7, opening sentence.

- Fitzgerald 2000, pp. vii–viii: Tanner's introduction to the Penguin Books edition.

- Hill, Burns & Shillingsburg 2002, p. 331: In early November he wrote Perkins that "I have now decided to stick to the title I put on the book. Trimalchio in West Egg."

- Fitzgerald & Perkins 1971, p. 87: "When Ring Lardner came in the other day I told him about your novel and he instantly balked at the title. 'No one could pronounce it,' he said; so probably your change is wise on other than typographical counts."

- Bruccoli 2002, pp. 206–07

- Tate 2007, p. 87: "He settled on The Great Gatsby in December 1924, but in January and March 1925 he continued to express his concern to Perkins about the title, cabling from CAPRI on March 19: CRAZY ABOUT TITLE UNDER THE RED WHITE AND BLUE STOP WHART [sic] WOULD DELAY BE."

- Lipton 2013: "However, nearing the time of publication, Fitzgerald, who despised the title The Great Gatsby and toiled for months to think of something else, wrote to Perkins that he had finally found one: Under the Red, White, and Blue. Unfortunately, it was too late to change."

- The Guardian 2013: "At the last minute, [Fitzgerald] had asked his editor if they could change the new novel's title to Under the Red, White, and Blue, but it was too late."

- Lazo 2003, p. 75: "When the book was published on April 10, 1925, the critics raved."

- Bruccoli 2002, pp. 215–17

- West 2002.

- West 2013: "Luhrmann was also interested in Trimalchio, the early version of The Great Gatsby."

- Alter 2013: "Gatsby comes across as more confident and aggressive in Trimalchio during a confrontation with romantic rival Tom Buchanan at the Plaza Hotel, challenging Tom's assertion that Gatsby and Daisy's affair is 'a harmless little flirtation.'"

- Clark 1925.

- Ford 1925: "The story [...] leaves the reader in a mood of chastened wonder, in which fact after fact, implication after implication is pondered over, weighed and measured. And when all are linked together, the weight of the story as a revelation of life and as a work of art becomes apparent."

- New York Post 1925.

- New York Herald Tribune 1925.

- Mencken 1925: "The Great Gatsby is in form no more than a glorified anecdote, and not too probable at that. The story for all its basic triviality has a fine texture; a careful and brilliant finish... What gives the story distinction is something quite different from the management of the action or the handling of the characters; it is the charm and beauty of the writing."

- Mencken 1925.

- Eagleton 1925: "[Fitzgerald] is considered a Roman candle which burned brightly at first but now flares out."

- McClure 1925.

- Coghlan 1925.

- Snyder 1925.

- Mizener 1951, p. 167.

- Bruccoli 2000, p. 175.

- Rimer 2008.

- Gatsby By The Numbers: "When 'Gatsby' author F. Scott Fitzgerald died in 1940, he thought he was a failure."

- Fitzgerald's obituary 1940: "The best of his books, the critics said, was The Great Gatsby. When it was published in 1925 this ironic tale of life on Long Island, at a time when gin was the national drink and sex the national obsession, it received critical acclaim. In it Mr. Fitzgerald was at his best."

- Mizener 1960: "Writers like John O'Hara were showing its influence and younger men like Edward Newhouse and Budd Schulberg, who would presently be deeply affected by it, were discovering it."

- Wittels 1945: "Troops showed interest in books about the human mind and books with sexual situations were grabbed up eagerly. One soldier said that books with 'racy' passages were as popular as 'pin-up girls'."

- Cole 1984, p. 28: "One hundred fifty-five thousand ASE copies of The Great Gatsby were distributed-as against the twenty-five thousand copies of the novel printed by Scribners between 1925 and 1942."

- Verghis 2013.

- Mizener 1951.

- Mizener 1951, p. 183.

- Pearson 1970, p. 638: "[Fitzgerald] was the self appointed spokesman for the 'Jazz Age,' a term he takes credit for coining, and he gave it its arch-high priest and prophet, Jay Gatsby, in his novel The Great Gatsby."

- Pearson 1970, p. 638.

- Pearson 1970, p. 645.

- The Guardian 2013.

- Fitzgerald 1991, p. 5.

- Person 1978, p. 253.

- Person 1978, pp. 250–257.

- Donahue 2013: "Often dismissed as a selfish ditz, is Daisy victimized by a society that offers her no career path except marriage to big bucks?"

- Person 1978, p. 250.

- Person 1978, p. 256.

- Bruccoli 2002, p. 156.

- Gillespie 2013.

- Keeler 2018, pp. 174–188.

- Krystal 2015.

- Berrin 2013.

- Grossberg 2009.

- Washington Ballet 2014.

- Aguirre 2011.

- Norman 2013.

- Farrell 2013.

- Carter 2010.

- Paskin 2010.

- Metacritic.com 2012.

- Bell 2011.

- Crouch 2011.

- Kirk, Chris; Morgan, Andrew; Wickman, Forrest (May 6, 2013). "The Great Gatsby: The Video Game". Slate. ISSN 1091-2339. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- Dixon 2003.

- Hischak 2012, pp. 85-86.

- Goldberg 2007.

- Wakeman 2014.

- Stevens 1999.

- Douglas 1950.

- White 2007.

- Forrest 2012.

- Hyatt 2006, pp. 49-50.

- Playbill 1926: Reproduction of original program at the Ambassador Theatre in 1926.

- Tredell 2007, pp. 93–95.

- Levy 2006.

- Arizona Theatre 2012.

- Brantley 2010.

Bibliography

Print sources

- Batchelor, Bob (2013). Gatsby: The Cultural History of the Great American Novel. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-8108-9195-1. Retrieved July 15, 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Books on Our Table". The New York Post. May 5, 1925.

- Bruccoli, Matthew Joseph, ed. (2000). F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby: A Literary Reference. New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7867-0996-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- ——— (2002). Some Sort of Epic Grandeur: The Life of F. Scott Fitzgerald (2nd rev. ed.). Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-57003-455-8. Retrieved February 25, 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Churchwell, Sarah (2013). Careless People: Murder, Mayhem, and the Invention of The Great Gatsby. Little, Brown Book Group. ISBN 978-1-84408-767-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Coghlan, Ralph (April 25, 1925). "F. Scott Fitzgerald". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. St. Louis, Missouri. p. 11. Retrieved January 2, 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cole, John Y., ed. (1984). Books in Action: The Armed Services Editions. Washington: Library of Congress. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-8444-0466-0. Retrieved May 22, 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Conor, Liz (June 22, 2004). The Spectacular Modern Woman: Feminine Visibility in the 1920s. Indiana University Press. p. 301. ISBN 978-0-253-21670-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Curnutt, Kirk (2004). A Historical Guide to F. Scott Fitzgerald. Oxford University Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-19-515303-3. Retrieved October 11, 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Drudzina, Douglas (2006). Teaching F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby from Multiple Critical Perspectives. Prestwick House. ISBN 978-1-58049-174-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Eagleton, Harvey (May 10, 1925). "Prophets of the New Age: III. F. Scott Fitzgerald". The Dallas Morning News. Dallas, Texas.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Eble, Kenneth (Winter 1974). "The Great Gatsby". College Literature. 1 (1): 34–47. ISSN 0093-3139. JSTOR 25111007.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fitzgerald, Francis Scott; Perkins, Maxwell (1971). Kuehl, John; Bryer, Jackson R. (eds.). Dear Scott/Dear Max: The Fitzgerald-Perkins Correspondence. Macmillan Publishing Company. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-02-538481-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fitzgerald, F. Scott (April 2003) [1945]. "Echoes of the Jazz Age". In Wilson, Edmund (ed.). The Crack-Up. New Directions. ISBN 978-0-8112-1820-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- ———— (August 30, 1991) [1925]. Bruccoli, Matthew J. (ed.). The Great Gatsby. The Cambridge Edition of the Works of F. Scott Fitzgerald. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-40230-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- ———— (2006) [1925]. Bloom, Harold (ed.). The Great Gatsby. New York: Chelsea House Publishers. p. 95. ISBN 978-1-4381-1454-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- ———— (2000) [1925]. Tanner, Tony (ed.). The Great Gatsy. London: Penguin Books. pp. vii–viii. ISBN 978-0-14-118263-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- ———— (1963). Turnbull, Andrew (ed.). The Letters of F. Scott Fitzgerald. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 189.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- ———— (1997). Tredell, Nicolas (ed.). F. Scott Fitzgerald: The Great Gatsby. Columbia Critical Guides. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 184. ISBN 978-0-231-11535-3. ISSN 1559-3002.

- Gross, Dalton (1998). Understanding the Great Gatsby: A Student Casebook to Issues, Sources, and Historical Documents. Literature in Context. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. p. 167. ISBN 978-0-313-30097-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hemingway, Ernest (1964). A Moveable Feast. New York: Scribner. p. 176. ISBN 978-0-684-82499-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hill, W. Speed; Burns, Edward M.; Shillingsburg, Peter L. (2002). Text: An Interdisciplinary Annual of Textual Studies. 14. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-11272-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hischak, Thomas S. (June 18, 2012). American Literature on Stage and Screen: 525 Works and Their Adaptations. McFarland & Company. pp. 85–86. ISBN 978-0-7864-6842-3. Retrieved January 1, 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hyatt, Wesley (2006). Emmy Award Winning Nighttime Television Shows, 1948-2004. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. pp. 49–50. ISBN 0-7864-2329-3. Retrieved January 1, 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Karolides, Nicholas J.; Bald, Margaret; Sova, Dawn B. (2011). 120 Banned Books: Censorship Histories of World Literature (Second ed.). Checkmark Books. p. 499. ISBN 978-0-8160-8232-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Keeler, Kyle (2018). "The Great Global Warmer: Jay Gatsby as a Microcosm of Climate Change". The F. Scott Fitzgerald Review. 16 (1): 174–188. doi:10.5325/fscotfitzrevi.16.1.0174. JSTOR 10.5325/fscotfitzrevi.16.1.0174.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lazo, Caroline Evensen (2003). F. Scott Fitzgerald: Voice of the Jazz Age. Twenty-First Century Books. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-8225-0074-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Leader, Zachary (September 21, 2000). "Daisy Packs Her Bags". London Review of Books. 22 (18): 13–15. ISSN 0260-9592. Retrieved February 24, 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McClure, John (May 31, 1925). "Literature—And Less". The Times-Picayune. New Orleans, Louisiana.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McCullen, Bonnie Shannon (2007). "This Tremendous Detail: The Oxford Stone in the House of Gatsby". In Assadi, Jamal; Freedman, William (eds.). A Distant Drummer: Foreign Perspectives on F. Scott Fitzgerald. New York: Peter Lang. pp. 11–20. ISBN 978-0-8204-8851-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mencken, H. L. (May 3, 1925). "Scott Fitzgerald and His Work". The Chicago Daily Tribune.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mizener, Arthur (1951). The Far Side of Paradise: A Biography of F. Scott Fitzgerald. Boston: Houghton-Mifflin Company. ISBN 978-1-199-45748-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- O'Meara, Lauraleigh (2002). Lost City: Fitzgerald's New York (1st ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-86701-6. Retrieved May 21, 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Perkins, Maxwell Evarts (2004) [1950]. Bruccoli, Matthew Joseph; Baughman, Judith S. (eds.). The Sons of Maxwell Perkins: Letters of F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, Thomas Wolfe, and Their Editor. University of South Carolina Press. pp. 27–30. ISBN 978-1-57003-548-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pearson, Roger L. (May 1970). "Gatsby: False Prophet of the American Dream". The English Journal. 59 (5): 638–642, 645. doi:10.2307/813939. JSTOR 813939.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Person, Leland S. (May 1978). "Herstory' and Daisy Buchanan" (PDF). American Literature. 50 (2): 250–257. doi:10.2307/2925105. JSTOR 2925105. Retrieved July 4, 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Randall, Mónica (2003). The Mansions of Long Island's Gold Coast. Rizzoli. pp. 275–277. ISBN 978-0-8478-2649-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Scribner, Charles, III (Winter 1992). "Celestial Eyes: From Metamorphosis to Masterpiece" (PDF). Princeton University Library Chronicle (Originally published as a brochure to celebrate the Cambridge Edition of The Great Gatsby) (published October 24, 1991). 53 (2): 140–155. doi:10.2307/26410056. JSTOR 26410056. Retrieved July 27, 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Snyder, Ruth (April 15, 1925). "A Minute or Two with Books—F. Scott Fitzgerald Ventures". New York Evening World.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tate, Mary Jo (2007). Critical Companion to F. Scott Fitzgerald: A Literary Reference to His Life and Work. Infobase Publishing. p. 326. ISBN 978-1-4381-0845-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tredell, Nicolas (February 28, 2007). The Great Gatsby – A Reader's Guide. London: Continuum Publishing. pp. 93–95. ISBN 978-1-4411-9193-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Turns with a Bookworm". New York Herald Tribune. April 12, 1925.

- Vanderbilt, Arthur T. (1999). The Making of a Bestseller: From Author to Reader. McFarland. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-7864-0663-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- West, James L. W., III (July 2002). Trimalchio: An Early Version of 'The Great Gatsby'. The Cambridge Edition of the Works of F. Scott Fitzgerald. Cover Design by Dennis M. Arnold. Cambridge University Press. p. xi. ISBN 978-0-521-89047-2. Retrieved July 4, 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Whipple, Kit (2019). Cleveland's Colorful Characters. Murrells Inlet: Covenant Books. p. 85. ISBN 978-1-64559-326-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wittels, David G. (June 23, 1945). "What the G.I. Reads". The Saturday Evening Post. 217 (52). Indianapolis. pp. 11, 91–92. OCLC 26501505.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Online sources

- Aguirre, Abby (November 4, 2011). "Gatsby En Pointe". The New York Times. Retrieved April 1, 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Alter, Alexandra (April 19, 2013). "A Darker, More Ruthless Gatsby". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on July 3, 2013. Retrieved July 11, 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Alter, Alexandra (December 29, 2018). "Mickey Mouse Will Be Public Domain Soon—Here's What That Means". Retrieved July 10, 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Andersen, Kurt (November 25, 2010). "American Icons: The Great Gatsby". Studio 360. Public Radio International. 14:26. Archived from the original on October 13, 2013. Retrieved May 22, 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Arizona Theatre Company: The Great Gatsby". Arizonatheatre.org. Archived from the original on November 6, 2013. Retrieved December 11, 2013.

- Baker, Kelly J. (November 25, 2016). "White-Collar Supremacy". The New York Times. Retrieved January 13, 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bell, Melissa (February 25, 2011). "Great Gatsby 'Nintendo' Game Released Online". The Washington Post. Retrieved February 15, 2011.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Berrin, Danielle (May 23, 2013). "The Great Gatsby's Jew". The Jewish Journal of Greater Los Angeles. Retrieved July 4, 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Borrelli, Christopher (May 7, 2013). "Revisiting Ginevra King, The Lake Forest Woman Who Inspired 'Gatsby'". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved October 21, 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brantley, Ben (December 16, 2010). "Hath Not a Year Highlights? Even This One?". The New York Times. Retrieved May 1, 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Carter, Vanessa (July 15, 2010). "Classic Adventures: The Great Gatsby". Gamezebo. Archived from the original on October 2, 2012. Retrieved April 20, 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Churchwell, Sarah (May 3, 2013). "What Makes The Great Gatsby Great?". The Guardian. Retrieved October 11, 2013.

- "Classic Adventures: The Great Gatsby for iPhone/iPad Reviews". Metacritic. December 8, 2012. Retrieved November 25, 2013.

- Clark, Edwin (April 19, 1925). "Scott Fitzgerald Looks into Middle Age". The New York Times. Retrieved May 11, 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Crouch, Ian (February 16, 2011). "Nintendo Lit: Gatsby and Tom Sawyer". The New Yorker. Retrieved February 24, 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dixon, Wheeler Winston (2003). "The Three Film Versions of The Great Gatsby: A Vision Deferred". Literature-Film Quarterly. Salisbury, Maryland. 31 (4): 287–294. Archived from the original on October 13, 2013. Retrieved October 11, 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Donahue, Deirdre (May 7, 2013). "Five Reasons 'Gatsby' Is The Great American Novel". USA Today. Retrieved July 5, 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Donahue, Deirdre (May 7, 2013). "'The Great Gatsby' By The Numbers". USA Today. Retrieved May 12, 2013.

- Douglas, Kirk (January 1, 1950). "Family Hour of Stars: The Great Gatsby". Radioechoes.com. Archived from the original on April 9, 2016. Retrieved July 21, 2015.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Farrell, Aimee (March 7, 2013). "The Great Gatsby's Ballet Makeover". Vogue. Condé Nast. Retrieved March 29, 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fitzgerald, F. Scott. "F. Scott Fitzgerald's Ledger". Irvin Department of Rare Books and Special Collections. University of South Carolina Press. Retrieved April 29, 2013.

- ———— (July 1922). "Something Extraordinary". Letters of Note. Images by Gareth M. Lettersofnote.com. Retrieved May 24, 2013.

- Flanagan, Thomas (December 21, 2000). "Fitzgerald's 'Radiant World'". The New York Review of Books. Retrieved May 24, 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ford, Lillian C. (May 10, 1925). "The Seamy Side of Society". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 11, 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Forrest, Robert (May 12, 2012). "BBC Radio 4 — Classic Serial, The Great Gatsby, Episode 1". BBC. London. Retrieved November 25, 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gillespie, Nick (May 2, 2013). "The Great Gatsby's Creative Destruction". Washington, D.C.: Reason. Retrieved May 12, 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Goldberg, Carole (March 18, 2007). "The Double Bind By Chris Bohjalian". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved May 22, 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Grossberg, Michael (April 20, 2009). "Literary Classic 'Great Gatsby' To Come To Life On Balletmet Stage". The Columbus Dispatch. Retrieved August 28, 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Haglund, David (May 7, 2013). "The Forgotten Childhood of Jay Gatsby". Slate. Retrieved July 11, 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Holowka, David (December 17, 2009). "The Iron Triangle, Part 1 - Wilson's Garage". ArchiTakes. Retrieved July 4, 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hoover, Bob (May 10, 2013). "'The Great Gatsby' Still Challenges Myth of American Dream". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved May 10, 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Howell, Peter (May 5, 2013). "Five Things You Didn't Know About The Great Gatsby". The Star. Toronto. Retrieved May 5, 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kellogg, Carolyn (April 20, 2011). "Last Gasp of the Gatsby House". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 26, 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Krystal, Arthur (July 20, 2015). "Fitzgerald and the Jews". The New Yorker. Retrieved July 4, 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Levy, Simon (July 2006). "The Great Gatsby Play - Official Website". TheGreatGatsbyPlay.com. Retrieved November 25, 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lopate, Leonard (June 17, 2014). "Murder, Mayhem, and the Invention of The Great Gatsby". Leonard Lopate Show. Retrieved July 4, 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lipton, Gabrielle (May 6, 2013). "Where Is Jay Gatsby's Mansion?". Slate. The Slate Group, a Division of The Washington Post Company. Retrieved May 6, 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mizener, Arthur (April 24, 1960). "Gatsby, 35 Years Later". The New York Times. Retrieved July 29, 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Murphy, Mary Jo (September 30, 2010). "Eyeing the Unreal Estate of Gatsby Esq". The New York Times. Retrieved July 4, 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Norman, Neil (May 17, 2013). "Dance Review: The Great Gatsby". The Sunday Express. Retrieved September 19, 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Paskin, Willa (July 15, 2010). "The Great Gatsby, Now a Video Game – Vulture". New York Magazine. Retrieved August 30, 2010.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Powers, Thomas (July 4, 2013). "The Road to West Egg". London Review of Books. 13. pp. 9–11. Retrieved July 4, 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rimer, Sara (February 17, 2008). "Gatsby's Green Light Beckons a New Set of Strivers". The New York Times. Retrieved July 8, 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Scott Fitzgerald, Author, Dies at 44". The New York Times. December 23, 1940. Archived from the original on January 3, 2013. Retrieved January 13, 2013.

- Smith, Dinitia (September 8, 2003). "Love Notes Drenched in Moonlight; Hints of Future Novels in Letters to Fitzgerald". The New York Times. Retrieved November 16, 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- SparkNotes Editors. "The Great Gatsby: Context". SparkNotes. Retrieved November 25, 2013.

- Stevens, David (December 29, 1999). "Harbison Mixes Up A Great 'Gatsby'". The New York Times. Retrieved April 8, 2011.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Symkus, Ed (May 4, 2013). "'Gatsby': What's So Great?". Boston Globe. Retrieved May 5, 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "The Girl at the Grand Palais". The Economist. London: The Economist Group. December 22, 2012. Retrieved March 27, 2013.

- "The Great Gatsby — The Broadway Play". Playbill. New York City: TotalTheater. Retrieved July 4, 2019.

- "The Washington Ballet: The Great Gatsby". Kennedy Center. Archived from the original on April 7, 2014. Retrieved April 1, 2014.

- Verghis, Sharon (May 4, 2013). "Careless People of F. Scott Fitzgerald's Great Gatsby Have a Modern Equivalent". The Australian. Surry Hills, New South Wales. Retrieved May 5, 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wakeman, Jessica (April 8, 2014). "Author Sara Benincasa Talks Young Adult Fiction, Zelda Fitzgerald & Women In Comedy". The Frisky. Retrieved November 29, 2014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- West, James L. W., III (April 10, 2013). "What Baz Luhrmann Asked Me About The Great Gatsby". The Huffington Post. New York. Retrieved July 27, 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- White, Trevor (December 10, 2007). "BBC World Service Programmes — The Great Gatsby". BBC. London. Retrieved August 30, 2010.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wulick, Anna (November 8, 2018). "Understanding The Great Gatsby First Line and Epigraph". PrepScholar.com. Retrieved December 15, 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Zuckerman, Esther (April 29, 2013). "The Finances of F. Scott Fitzgerald, Handwritten by Fitzgerald". The Atlantic Wire. Washington, D.C.: The Atlantic Media Company. Retrieved July 4, 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: The Great Gatsby |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Great Gatsby. |

- The Great Gatsby at Faded Page (Canada)

- Fitzgerald, F. Scott. The Great Gatsby (plain text ed.). Project Gutenberg Australia.

- "In Gatsby's Tracks – Locating the Valley of Ashes". litkicks.com.

- The Great Gatsby Play – Authorized and Granted Exclusive Rights by the Fitzgerald Estate

- Conversations from Penn State: Writers of the Lost Generation with Linda Patterson Miller discussing F. Scott Fitzgerald and his relationships with other writers of the "Lost Generation"

- Oloizia, Jeff; Dhanraj, Emanuel (9 April 2013). "A Book by Its Covers" (interactive photo gallery). T: The New York Times Style Magazine.

- An Index to The Great Gatsby