Mensheviks

The Mensheviks (Russian: меньшевики́, 'minority')[1][2] were one of the three dominant factions in the Russian socialist movement, the others being the Bolsheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries.

меньшевики́ | |

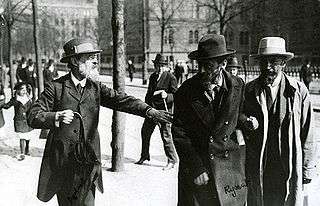

Leaders of the Menshevik Party at Norra Bantorget in Stockholm, Sweden, May 1917 (Pavel Axelrod, Julius Martov, and Alexander Martinov) | |

| Formation | 1903 |

|---|---|

| Extinction | 1921 |

| Products | Rabochaia gazeta (Workers' gazette) |

Key people | Julius Martov Pavel Axelrod Alexander Martinov Fyodor Dan Irakli Tsereteli Leon Trotsky (later Bolshevik) Noe Zhordania |

Parent organization | Russian Social-Democratic Labour Party |

Formerly called | "softs" |

The factions emerged in 1903 following a dispute within the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) between Julius Martov and Vladimir Lenin. The dispute originated at the 2nd Congress of the RSDLP, ostensibly over minor issues of party organization. Martov's supporters, who were in the minority in a crucial vote on the question of party membership, came to be called Mensheviks, derived from the Russian меньшинство ('minority'), while Lenin's adherents were known as Bolsheviks, from большинство ('majority').[3][4][5][6][7]

Despite the naming, neither side held a consistent majority over the course of the entire 2nd Congress, and indeed the numerical advantage fluctuated between both sides throughout the rest of the RSDLP's existence until the Russian Revolution. The split proved to be long-standing and had to do both with pragmatic issues based in history, such as the failed Revolution of 1905 and theoretical issues of class leadership, class alliances and interpretations of historical materialism. While both factions believed that a proletarian revolution was necessary, the Mensheviks generally tended to be more moderate, and more positive towards the liberal opposition and the peasant-based Socialist Revolutionary Party.[8][9]

History of the split

1903–1906

At the 2nd Congress of the RSDLP in August 1903, Julius Martov and Vladimir Lenin disagreed, firstly, in regards to which persons should be in the editorial committee of Iskra, the Party newspaper; secondly, in regards to the definition of a "party member" in the future Party statute:[10]

- Lenin's formulation required the party member to be a member of one of the Party's organizations

- Martov's only stated that he should work under the guidance of a Party organization.

Although the difference in definitions was small, with Lenin's being slightly more exclusive, it was indicative of what became an essential difference between the philosophies of the two emerging factions: Lenin argued for a small party of professional revolutionaries with a large fringe of non-party sympathizers and supporters, whereas Martov believed it was better to have a large party of activists with broad representation.

Martov's proposal was accepted by the majority of the delegates (28 votes to 23).[10] However, after seven delegates stormed out of the Congress—five of whom were representatives of the Jewish Bund who left in protest about their own federalist proposal being defeated[10]—Lenin's supporters won a slight majority, which was reflected in the composition of the Central Committee and the other central party organs elected at the Congress. This was also the reason behind the naming of the factions. It was later hypothesized that Lenin had purposely offended some of the delegates in order to have them leave the meeting in protest, giving him a majority. However, Bolsheviks and Mensheviks were united in voting against the Bundist proposal, which lost 41 to 5.[11] Despite the outcome of the Congress, the following years saw the Mensheviks gathering considerable support among regular social democrats and effectively building up a parallel party organization.

1906–1916

At the 4th Congress of the RSDLP in 1906, a reunification was formally achieved.[12] In contrast to the 2nd Congress, the Mensheviks were in the majority from start to finish, yet Martov's definition of a party member, which had prevailed at the 1st Congress, was replaced by Lenin's. On the other hand, numerous disagreements about alliances and strategy emerged. The two factions kept their separate structures and continued to operate separately.

As before, both factions believed that Russia was not developed enough to make socialism possible and that therefore the revolution which they planned, aiming to overthrow the Tsarist regime, would be a bourgeois-democratic revolution. Both believed that the working class had to contribute to this revolution. However, after 1905 the Mensheviks were more inclined to work with the liberal bourgeois democratic parties such as the Constitutional Democrats because these would be the "natural" leaders of a bourgeois revolution. In contrast, the Bolsheviks believed that the Constitutional Democrats were not capable of sufficiently radical struggle and tended to advocate alliances with peasant representatives and other radical socialist parties such as the Socialist Revolutionaries. In the event of a revolution, this was meant to lead to a dictatorship of the proletariat and the peasantry, which would carry the bourgeois revolution to the end. The Mensheviks came to argue for predominantly legal methods and trade union work, while the Bolsheviks favoured armed violence.

Some Mensheviks left the party after the defeat of 1905 and joined legal opposition organisations. After a while, Lenin's patience wore out with their compromising and, in 1908, he called these Mensheviks "liquidationists."

1912–14

In 1912, the RSDLP had its final split, with the Bolsheviks constituting the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, and the Mensheviks the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party. The Menshevik faction split further in 1914 at the beginning of World War I. Most Mensheviks opposed the war, but a vocal minority supported it in terms of "national defense."

1917 revolutions

After the overthrow of the Romanov dynasty by the February Revolution in 1917, the Menshevik leadership led by Irakli Tsereteli demanded that the government pursue a "fair peace without annexations," but in the meantime supported the war effort under the slogan of "defense of the revolution." Along with the other major Russian socialist party, the Socialist Revolutionaries (also known as эсеры, esery), the Mensheviks led the emerging network of soviets, notably the Petrograd Soviet in the capital, throughout most of 1917.

With the monarchy gone, many social democrats viewed previous tactical differences between the Mensheviks and the Bolsheviks as a thing of the past and a number of local party organizations were merged. When Bolshevik leaders Lev Kamenev, Joseph Stalin, and Matvei Muranov returned to Petrograd from Siberian exile in early March 1917 and assumed the leadership of the Bolshevik Party, they began exploring the idea of a complete re-unification of Bolsheviks and Mensheviks at the national level, which Menshevik leaders were willing to consider. However, Lenin and his deputy Grigory Zinoviev returned to Russia from exile in Switzerland on 3 April and re-asserted control of the Bolshevik Party by late April 1917, taking it in a more radical direction. They called for an immediate revolution and transfer of all power to the soviets, which made any re-unification impossible.

In March–April 1917, the Menshevik leadership conditionally supported the newly formed liberal Russian Provisional Government. After the collapse of the first Provisional Government on 2 May over the issue of annexations, Tsereteli convinced the Mensheviks to strengthen the government for the sake of "saving the revolution" and enter a socialist-liberal coalition with Socialist Revolutionaries and liberal Constitutional Democrats, which they did on 17 May. With Martov's return from European exile in early May, the left-wing of the party challenged the party's majority led by Tsereteli at the first post-revolutionary party conference on 9 May, but the right wing prevailed 44–11. From then on, the Mensheviks had at least one representative in the Provisional Government until it was overthrown by the Bolsheviks during the October Revolution.

With Mensheviks and Bolsheviks diverging, Mensheviks and non-factional social democrats returning from exile in Europe and United States in spring-summer of 1917 were forced to take sides. Some re-joined the Mensheviks. Others, like Alexandra Kollontai, joined the Bolsheviks. A significant number, including Leon Trotsky and Adolf Joffe, joined the non-factional Petrograd-based anti-war group called Mezhraiontsy, which merged with the Bolsheviks in August 1917. A small yet influential group of social democrats associated with Maxim Gorky's newspaper Novaya Zhizn (New Life) refused to join either party.

After the 1917 Revolution

The 1917 split in the party crippled the Mensheviks' popularity and they received 3.2% of the vote during the Russian Constituent Assembly election in November 1917 compared to the Bolsheviks' 23% and the Socialist Revolutionaries' 37%. The Mensheviks got just 3.3% of the national vote, but in the Transcaucasus they got 30.2%. 41.7% of their support came from the Transcaucasus and in Georgia, about 75% voted for them.[13] The right-wing of the Menshevik Party supported actions against the Bolsheviks while the left-wing, the majority of the Mensheviks at that point, supported the left in the ensuing Russian Civil War. However, Martov's leftist Menshevik faction refused to break with the right-wing of the party, resulting in their press being sometimes banned and only intermittently available.

The Mensheviks opposed War Communism and in 1919 suggested an alternative programme.[14] During World War I, some anti-war Mensheviks had formed a group called Menshevik-Internationalists. They were active around the newspaper Novaya Zhizn and took part in the Mezhraiontsy formation. After July 1917 events in Russia, they broke with the Menshevik majority that supported continued war with Germany. The Mensheviks-Internationalists became the hub of the Russian Social Democratic Workers' Party (of Internationalists). Starting in 1920, right-wing Mensheviks-Internationalists emigrated, some of them pursuing anti-Bolshevik activities.[15]

The Democratic Republic of Georgia was a stronghold of the Mensheviks. In parliamentary elections held on 14 February 1919, they won 81.5% of the votes and the Menshevik leader Noe Zhordania became Prime Minister. Prominent members of Georgian Menshevik Party were Noe Ramishvili, Evgeni Gegechkori, Akaki Chkhenkeli, Nikolay Chkheidze and Alexandre Lomtatidze. After the occupation of Georgia by the Bolsheviks in 1921, many Georgian Mensheviks led by Zhordania fled to Leuville-sur-Orge, France, where they set up the Government of the Democratic Republic of Georgia in Exile. In 1930, Ramishvili was assassinated by a Soviet spy in Paris.

Menshevism was finally made illegal after the Kronstadt uprising of 1921. A number of prominent Mensheviks emigrated thereafter. Martov went to Germany, where he established the paper Socialist Messenger. He died in 1923. In 1931, the Menshevik Trial was conducted by Stalin, an early part of the Great Purge. The Messenger moved with the Menshevik center from Berlin to Paris in 1933 and then in 1939 to New York City, where it was published until 1965.[16]

See also

References

- Radziwill, Catherine. [1915] 1920. "Bulgaria Joins the Great Wars." Pp. 326–32 in The Great Events of the Great War 3, edited by C. F. Horne. New York: National Alumni. p. 328.

- Aldanov, Mark Aleksandrovich. 1922. Lenin. New York: E. P. Dutton. OL 2400504W. p. 10

- Brovkin, Vladimir N. 1991. The Mensheviks After October. Cornell University Press.

- Basil, John D. 1983. The Mensheviks in the Revolution of 1917. Slavica Publishers.

- Antonov-Saratovsky, Vladimir. 1931. The Trial of the Mensheviks: The verdict and sentence passed on the participants in the counter-revolutionary organization of the Mensheviks. Soviet Union: Centrizdai.

- Broido, Vera. 1987. Lenin and the Mensheviks: The persecution of Socialists Under Bolshevism. Gower.

- Ascher, Abraham. 1976. The Mensheviks in the Russian Revolution. Cornell University Press.

- Burbank, Jane (1 January 1985). "Waiting for the People's Revolution: Martov and Chernov in Revolutionary Russia 1917–1923". Cahiers du Monde Russe et Soviétique. 26 (3/4): 375–394. doi:10.3406/cmr.1985.2051. JSTOR 20170079.

- Smith, S. A. (21 February 2002). The Russian Revolution: A Very Short Introduction. OUP Oxford. p. 17. ISBN 9780191578366.

- Lenin, V.I (1903). Second Congress of the League of Russian Revolutionary Social-Democracy Abroad. Moscow. pp. 26–31, 92–103.

- Johnpoll, Bernard K. 1967. The Politics of Futility; The General Jewish Workers Bund of Poland, 1917–1943. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. pp. 30–31.

- "Lenin: 1906/ucong: Statement in Support of Muratov's (Morozov's) Amendment Concerning a Parliamentary Social-Democratic Group". www.marxists.org. Retrieved 16 January 2016.

- Radkey, Oliver Henry. 1950. The Election to the Russian Constituent Assembly of 1917. Harvard University Press.

- O'Brien, James. 11 August 2012. "What is to be done: The Menshevik Programme July 1919." Spirit of Contradiction. Retrieved on 26 July 2013.

- Liebich, Andre (1 January 1995). "Mensheviks Wage the Cold War". Journal of Contemporary History. 30 (2): 247–264. doi:10.1177/002200949503000203. JSTOR 261050.

- Kowalski, Werner. 1985. Geschichte der sozialistischen arbeiter-internationale: 1923–1940. Berlin: Dtv Verlagsgesellschaft. pp. 336–37.

Further reading

- Ascher, Abraham, ed. 1976. The Mensheviks in the Russian Revolution. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Basil, John D. 1983. The Mensheviks in the Revolution of 1917. Columbus, OH: Slavica Publishers.

- Bourguina, A. M. 1968. Russian Social Democracy: The Menshevik Movement: A Bibliography. Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution on War, Revolution and Peace.

- Broido, Vera. 1987. Lenin and the Mensheviks: The Persecution of Socialists Under Bolshevism. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Brovkin, Vladimir. 1983. "The Mensheviks' Political Comeback: The Elections to the Provincial City Soviets in Spring 1918." Russian Review 42(1):1–50. JSTOR 129453.

- —— 1987. The Mensheviks After October: Socialist Opposition and the Rise of the Bolshevik Dictatorship. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- —— 1991. Dear Comrades: Menshevik Reports on the Bolshevik Revolution and the Civil War. Hoover Press.

- Galili, Ziva. 1989. The Menshevik Leaders in the Russian Revolution: Social Realities and Political Strategies. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Haimson, Leopold H., ed. 1974. The Mensheviks : From the Revolution of 1917 to the Second World War. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- —— 1988. The Making of Three Russian Revolutionaries: Voices from the Menshevik Past. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Liebich, André. 1997. From the Other Shore: Russian Social Democracy after 1921. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

External links

- marxists.org:glossary:/m/e "Menshevik Party", "Menshevik Internationalists". Glossary of Organisations: Me.

- "The Bolshevik-Menshevik Split." History Today.