Alfred, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha

Alfred (Alfred Ernest Albert; 6 August 1844 – 30 July 1900) reigned as Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha from 1893 to 1900. He was the second son and fourth child of Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom and Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. He was known as the Duke of Edinburgh from 1866 until he succeeded his paternal uncle Ernest II as the reigning Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha in the German Empire.

| Alfred | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duke of Edinburgh (more...) | |||||

Prince Alfred in 1881 | |||||

| Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha | |||||

| Reign | 22 August 1893 – 30 July 1900 | ||||

| Predecessor | Ernest II | ||||

| Successor | Charles Edward | ||||

| Born | 6 August 1844 Windsor Castle, Berkshire, England | ||||

| Died | 30 July 1900 (aged 55) Schloss Rosenau, Coburg, Duchy of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, German Empire | ||||

| Burial | 4 August 1900 | ||||

| Spouse | |||||

| Issue | |||||

| |||||

| House | Saxe-Coburg and Gotha | ||||

| Father | Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha | ||||

| Mother | Victoria, Queen of the United Kingdom | ||||

| Military career | |||||

| Allegiance | |||||

| Service/ | |||||

| Rank | Admiral of the Fleet | ||||

| Commands held | Commander-in-Chief, Plymouth Mediterranean Fleet Channel Fleet Admiral Superintendent of Naval Reserves, Malta HMS Galatea | ||||

Early life

Prince Alfred was born on 6 August 1844 at Windsor Castle to the reigning British monarch, Queen Victoria, and her husband, Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, the second son of Ernest I, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. He was second in the line of succession to the British throne behind his elder brother, the Prince of Wales.

Alfred was baptised by the Archbishop of Canterbury, William Howley, at the Private Chapel in Windsor Castle on 6 September 1844. His godparents were his mother's first cousin, Prince George of Cambridge (represented by his father, the Duke of Cambridge); his paternal aunt, the Duchess of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (represented by his maternal grandmother, the Duchess of Kent); and Queen Victoria's half-brother, the Prince of Leiningen (represented by the Duke of Wellington, Conservative Leader in the Lords).[1]

Alfred studied violin at Holyrood, Edinburgh, where his accompanist was Hungarian expatriate George Lichtenstein.[2]

Alfred remained second in line to the British throne from his birth until 8 January 1864, when his older brother Edward and his wife Alexandra of Denmark had their first son, Prince Albert Victor. Alfred became third in line to the throne and as Edward and Alexandra continued to have children, Alfred was further demoted in the order of succession.

Entering the Royal Navy

%2C_later_Duke_of_Edinburgh.jpg)

In 1856, at the age of 12, it was decided that Prince Alfred, in accordance with his own wishes, should enter the Royal Navy. A separate establishment was accordingly assigned to him, with Lieutenant J.C. Cowell, RE, as governor. He passed the examination in August 1858, and was appointed as midshipman in HMS Euryalus at the age of 14.[3] In July 1860, while on this ship, he paid an official visit to the Cape Colony, and made a very favourable impression both on the colonials and on the native chiefs.[4] He took part in a hunt at Hartebeeste-Hoek, resulting in the slaughter of large numbers of game animals.[5] On the abdication of King Otto of Greece, in 1862, Prince Alfred was chosen to succeed him, but the British government blocked plans for him to ascend the Greek throne, largely because of the Queen's opposition to the idea. She and her late husband had made plans for him to succeed to the Duchy of Saxe-Coburg.

Prince Alfred, therefore, remained in the navy, and was promoted to lieutenant on 24 February 1863, serving under Count Gleichen on the corvette HMS Racoon.[6] He was promoted to captain on 23 February 1866 and was appointed to the command of the frigate HMS Galatea in January 1867.[6]

Duke of Edinburgh

In the Queen's Birthday Honours on 24 May 1866, the Prince was created Duke of Edinburgh, Earl of Ulster, and Earl of Kent,[7] with an annuity of £15,000 granted by Parliament.[4] He took his seat in the House of Lords on 8 June.

While still in command of the Galatea, the Duke of Edinburgh started from Plymouth on 24 January 1867 for his voyage around the world. On 7 June 1867, he left Gibraltar, reached the Cape of Good Hope on 24 July and paid a royal visit to Cape Town on 24 August 1867 after landing at Simon's Town a while earlier. He landed at Glenelg, South Australia, on 31 October 1867.[4] Being the first member of the royal family to visit Australia, he was received with great enthusiasm. During his stay of nearly five months he visited Adelaide, Melbourne, Sydney, Brisbane and Tasmania.[4] Adelaide school Prince Alfred College was named in his honour to mark the occasion.

On 12 March 1868, on his second visit to Sydney, he was invited by Sir William Manning, President of the Sydney Sailors' Home, to picnic at the beachfront suburb of Clontarf to raise funds for the home. At the function, he was wounded in the back by a revolver fired by Henry James O'Farrell. Alfred was shot just to the right of his spine and was tended for the next two weeks by six nurses, trained by Florence Nightingale and led by Matron Lucy Osburn, who had just arrived in Australia in February 1868. In the violent struggle during which Alfred was shot, William Vial had managed to wrest the gun away from O'Farrell until bystanders assisted. Vial, a master of a Masonic Lodge, had helped to organise the picnic in honour of the Duke's visit and was presented with a gold watch[8] for securing Alfred's life. Another bystander, George Thorne, was wounded in the foot by O'Farrell's second shot.[9] O'Farrell was arrested at the scene, quickly tried, convicted and hanged on 21 April 1868.

On the evening of 23 March 1868, the most influential people of Sydney voted for a memorial building to be erected, "to raise a permanent and substantial monument in testimony of the heartfelt gratitude of the community at the recovery of HRH". This led to a public subscription which paid for the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital's construction.

Alfred soon recovered from his injury and was able to resume command of his ship and return home in early April 1868. He reached Spithead on 26 June 1868, after an absence of seventeen months.

He visited Hawaii in 1869 and spent time with the royal family there, where he was presented with leis upon his arrival. He was also the first member of the royal family to visit New Zealand, arriving in 1869 on HMS Galatea. He also became the first European prince to visit Japan and on 4 September 1869, he was received at an audience by the teenaged Emperor Meiji in Tokyo.

The Duke's next voyage was to India, where he arrived in December 1869 and Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), which he visited the following year. In both countries and at Hong Kong, which he visited on the way, he was the first British prince to set foot in the country. The native rulers of India vied with one another in the magnificence of their entertainments during the stay of three months.[4] In Ceylon a reception was given for him, by the request of the British, by Charles Henry de Soysa, the richest man in Ceylon, at his private residence which was consequently renamed, by permission, Alfred House; Alfred reportedly ate off gold plates with gold cutlery inlaid with jewels.[10][11][12]

Marriage

On 23 January 1874, the Duke of Edinburgh married the Grand Duchess Maria Alexandrovna of Russia, the second (and only surviving) daughter of Emperor Alexander II of Russia and his first wife Marie of Hesse and by Rhine, daughter of Ludwig II, Grand Duke of Hesse and by Rhine and Wilhelmine of Baden, at the Winter Palace, St Petersburg. To commemorate the occasion, a small English bakery made the now internationally popular Marie biscuit, with the Duchess' name imprinted on its top.[13] The Duke and Duchess of Edinburgh made their public entry into London on 12 March. The marriage, however, was not a happy one, and the bride was thought haughty by London Society.[14] She was surprised to discover that she had to yield precedence to the Princess of Wales and all of Queen Victoria's daughters and insisted on taking precedence before the Princess of Wales (the future Queen Alexandra) because she considered the Princess of Wales's family (the Danish royal family) as inferior to their own. Queen Victoria refused this demand, yet granted her precedence immediately after the Princess of Wales. Her father gave her the then-staggering sum of £100,000 as a dowry, plus an annual allowance of £32,000.[15]

Children

| Image | Name | Birth | Death | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prince Alfred | 15 October 1874 | 6 February 1899 | Hereditary Prince of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha from 22 August 1893 |

| Princess Marie | 29 October 1875 | 18 July 1938 | married, 10 January 1893, King Ferdinand I of Romania (1865–1927); had issue |

| Princess Victoria Melita | 25 November 1876 | 2 March 1936 | married (1), 9 April 1894, Ernst Ludwig, Grand Duke of Hesse and by Rhine; had issue; divorced 21 December 1901

(2) 8 October 1905, Grand Duke Kirill Vladimirovich of Russia; had issue | |

| Princess Alexandra | 1 September 1878 | 16 April 1942 | married, 20 April 1896, Ernst II, Prince of Hohenlohe-Langenburg; had issue |

| Unnamed son | 13 October 1879 | 13 October 1879 | stillborn | |

| Princess Beatrice | 20 April 1884 | 13 July 1966 | married, 15 July 1909, Infante Alfonso, Duke of Galliera; had issue |

Flag rank

Alfred was stationed in Malta for several years and his third child, Victoria Melita, was born there in 1876. Promoted rear-admiral on 30 December 1878, he became admiral superintendent of naval reserves, with his flag in the corvette HMS Penelope in November 1879.[16] Promoted to vice-admiral on 10 November 1882, he became Commander-in-Chief, Channel Fleet, with his flag in the armoured ship HMS Minotaur, in December 1883.[16] He became Commander-in-Chief, Mediterranean Fleet, with his flag in the armoured ship HMS Alexandra, in March 1886, and having been promoted to admiral on 18 October 1887,[17] he went on to be Commander-in-Chief, Plymouth in August 1890.[16] He was promoted to Admiral of the Fleet on 3 June 1893.[16]

Percy Scott wrote in his memoirs that "as a Commander-in-Chief, the Duke of Edinburgh had, in my humble opinion, no equal. He handled a fleet magnificently, and introduced many improvement in signals and manoeuvring." He "took a great interest in gunnery."[18] "The prettiest ship I have ever seen was the [Duke of Edinburgh's flagship] HMS Alexandra. I was informed that £2,000 had been spent by the officers on her decoration."[19]

Duchy of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha

On the death of his uncle, Ernest II, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha on 22 August 1893, the duchy fell to the Duke of Edinburgh, since his elder brother (the Prince of Wales) had renounced his right to the succession before he married. Alfred thereupon surrendered his British allowance of £15,000 a year and his seats in the House of Lords and the Privy Council, but he retained the £10,000 granted on his marriage to maintain Clarence House as his London residence.[20] At first regarded with some coldness as a "foreigner", he gradually gained popularity. By the time of his death in 1900, he had generally won the good opinion of his subjects.[4]

Alfred was exceedingly fond of music and took a prominent part in establishing the Royal College of Music.[4] He was a keen violinist, but had little skill. At a dinner party given by his brother, he was persuaded to play. Sir Henry Ponsonby wrote: 'Fiddle out of tune and noise abominable.'[21]

He was also a keen collector of glass and ceramic ware, and his collection, valued at half a million marks, was presented by his widow to the Veste Coburg, the enormous fortress on a hill top above Coburg.[4]

Later life

Alfred and Maria's only son, Alfred, Hereditary Prince of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, became involved in a scandal involving his mistress and apparently shot himself in January 1899, in the midst of his parents' twenty-fifth wedding anniversary celebrations at the Schloss Friedenstein in Gotha. He survived, but his embarrassed mother sent him off to Meran to recover, where he died two weeks later, on 6 February. His father was devastated.[22]:11

The Duke of Saxe-Coburg died of throat cancer on 30 July 1900 in a lodge adjacent to Schloss Rosenau, the ducal summer residence just north of Coburg. He was buried at the ducal family's mausoleum in the Friedhof am Glockenberg in Coburg.[23]:47 He was succeeded as the Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha by his nephew, Prince Charles Edward, Duke of Albany, the posthumous son of his youngest brother, Prince Leopold, Duke of Albany.[24]

He was survived by his mother, Queen Victoria, who had already outlived two of her children, Alice and Leopold. She died six months later.

Legacy

Manta alfredi is commonly known as Prince Alfred's manta ray.[25]

Tristan da Cunha

Edinburgh of the Seven Seas, the settlement on Tristan da Cunha, was named after Alfred after he visited the remote islands in 1867 while Duke of Edinburgh.

Australia

Royal Prince Alfred Hospital in Sydney, The Alfred Hospital in Melbourne, Prince Alfred College in Adelaide, Prince Alfred Park in Sydney, Prince Alfred Square in Parramatta, and the Royal Prince Alfred Yacht Club, now in Newport, are named in his honour.

New Zealand

The name of the small township of Alfredton (near Eketahuna in the lower North Island of New Zealand) honours the prince.[26]

South Africa

In Simon's Town, Prince Alfred Hotel was built in 1802 and renamed after the prince visited Cape Province in 1868. For more than two centuries Simon's Town has been an important naval base and harbour (first for the Royal Navy and now the South African Navy). The former hotel now houses the Backpackers' Hostel, opposite the harbour in the main street.

A Prince Alfred Street can be found in Pietermaritzburg, Queenstown, Grahamstown, Durban and Caledon. There is some opposition to Prince Alfred Street in Durban being renamed Florence Nzama Street. In Port Elizabeth there is a Prince Alfred's Terrace.

In Cape Town during his visit in 1868, Prince Alfred ceremoniously tipped the first load of rock to commence the building of the Breakwater. This was built by convict labour and formed the protective seawall for the new Cape Town Harbour, now redeveloped as the Victoria & Alfred Waterfront and a popular tourist and shopping destination.

Prince Alfred sailed into Port Elizabeth on 6 August 1860 as a midshipman on HMS Euryalus and celebrated his 16th birthday among its citizens.[27] Seven years later he sailed into Simon's Town as the Captain of HMS Galatea.

The Alfred Rowing Club was established in 1864 and was housed under the pier at Table Bay. It was named after Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh, who visited the Cape in 1860. It is the oldest organised sporting club in South Africa.[28]

The Port Elizabeth Rifle Corps was formed in 1856 under Sir George Grey's scheme to have a volunteer force to help secure the borders of the Cape Colony. Four years later it provided a Royal Guard to Prince Alfred and reportedly bore itself so well that, at the suggestion of the Governor, the Prince gave permission for it to be renamed Prince Alfred's Guard. It bears the name to the present day.

The opening ceremony of the South African Library was performed by Prince Alfred in 1860. An impressive portrait of the Prince hangs in the main reading room.[29]

The Port Elizabeth Chapter of the Memorable Order of Tin Hats, a veterans association, is known as the Prince Alfred Shellhole.[30]

Prince Alfred Hamlet is a small town in the Western Cape province.

Port Alfred, on the Kowie River in the Eastern Cape, was originally known as Port Frances after the daughter-in-law of the Governor of Cape Colony, Lord Charles Somerset. Of all the passes built in South Africa by the famous Andrew Geddes Bain and his son, Thomas, Prince Alfred's Pass remains, for many people, a favourite because of its lavish variety winding through some of the world's most unspoiled scenery.[31]

Philately

One of the stamp collectors in the British royal family, Prince Alfred won election as honorary president of The Philatelic Society, London in 1890. He may have inspired his nephew George V, who benefited after the Prince of Wales (later Edward VII) bought his brother Prince Alfred's collection. The merging of Alfred's and George's collections gave birth to the Royal Philatelic Collection.[32]

Russian navy

The Russian armoured cruiser Gerzog Edinburgski took its name from the Duke of Edinburgh.

Titles, styles, honours and arms

Titles and styles

- 6 August 1844 – 24 May 1866: His Royal Highness The Prince Alfred[33]

- 24 May 1866 – 23 August 1893: His Royal Highness The Duke of Edinburgh

- 23 August 1893 – 30 July 1900: His Royal Highness The Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha

Honours

- KG: Royal Knight of the Garter, 10 June 1863[36]

- KT: Extra Knight of the Thistle, 15 October 1864[37]

- KP: Knight of St. Patrick, 14 May 1880[38]

- GCB: Knight Grand Cross of the Bath (military), 25 May 1889[39]

- GCSI: Knight Grand Commander of the Star of India, 7 February 1870[40]

- GCMG: Knight Grand Cross of St Michael and St George, 29 June 1869[41]

- GCIE: Knight Grand Commander of the Indian Empire, 21 June 1887[42]

- GCVO: Knight Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order, 24 May 1899[43]

- PC: Privy Counsellor, 1866 – 1893

- KStJ: Knight of Justice of St. John[44]

.svg.png)

- Grand Cross of the Tower and Sword, 25 November 1858

- Grand Cross of the Sash of the Two Orders, 7 November 1889; Three Orders, 28 February 1894

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

- Grand Cross of the Ludwig Order, 15 May 1864

- Grand Cross of Philip the Magnanimous, 6 June 1865

.svg.png)

- Knight of the Black Eagle, 1864[49]

- Grand Cross of the Red Eagle, 1864

- Grand Commander of the Royal House Order of Hohenzollern, with Swords, 5 December 1878

- Knight of St. Andrew, May 1865

- Knight of St. Alexander Nevsky, May 1865

- Knight of the White Eagle, May 1865

- Knight of St. Anna, 1st Class, May 1865

- Knight of St. Stanislaus, 1st Class, May 1865

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

- Knight of the House Order of Fidelity, 1865[52]

- Grand Cross of the Zähringer Lion, 1865[53]

.svg.png)

_crowned.svg.png)

- Knight of the Annunciation, 15 July 1867[49]

- Grand Cross of Saints Maurice and Lazarus, 15 July 1867

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

- Grand Cross of the Order of Charles III, 9 July 1887[60]

- Knight of the Golden Fleece, 17 June 1888[61]

Arms

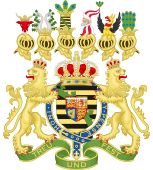

Prince Alfred gained use of the royal arms of the United Kingdom, charged with an inescutcheon of the shield of the Duchy of Saxony, representing his paternal arms, the whole differenced by a label argent of three points, the outer points bearing anchors azure, and the inner a cross gules. When he became the Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, his Saxon arms were his British arms inverted, as follows: the ducal arms of Saxony charged with an inescutcheon of the royal arms of the United Kingdom differenced with a label argent of three points, the outer points bearing anchors azure, and the inner a cross gules.

Prince Alfred's coat of arms as a British prince |

Prince Alfred's heraldic shield as a British prince |

Alfred's arms as Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha |

Heraldic shield as Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha |

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Alfred, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Footnotes

- "No. 20382". The London Gazette. 10 September 1844. p. 3149.

- The Musical Times and Singing-class Circular. 34. Novello. 1893. p. 156.

- Courtney, Nicholas; Foreword by Prince Andrew, Duke of York (2004). The Queen's Stamps: The Authorized History of the Royal Philatelic Collection. London: Methuen. p. 27. ISBN 0-413-77228-4.

...he set his heart from an early age on the Royal Navy with 'a passion which we, as his parents, believe not to have a right to subdue'

-

- "Progress of His Royal Highness, Prince Alfred Ernest Albert, through the Cape Colony, British Kaffraria, the Orange Free State, and Port Natal in the year 1860"

- Heathcote, p. 9.

- "No. 23119". The London Gazette. 25 May 1866. p. 3127.

- Vial, William. "Gold Watch presented by the Duke of Edinburgh". Realia. State Library of NSW. Retrieved 21 May 2014.

- "Emily Nuttall Thorne – 'Clontarf', an account of the attempted assassination of Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh, at Clontarf on 12 March 1868". diary. State Library of NSW. Retrieved 21 May 2014.

- Prins, Stephen. "The day the Queen came to Queen's Road". Sunday Times. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- Boyle, Richard. "A right royal tour". Sunday Times. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- Amerasinghe, Dr. A.R.B. "Bagatelle Road – will it be gone with the wind?". Sunday Times (Sri Lanka). Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- La Tienda. "2-Pack Maria Cookies by Cuetera". Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 9 November 2007.

- Van der Kiste, John. The Romanovs 1818–1959. Sutton Publishing, 1999. p.64. ISBN 0-7509-2275-3.

- Wimbles, John. The Daughter of Tsar Alexander II. Published in The Grand Duchesses. Eurohistory.com, 2014. p. 46.

- Heathcote, p. 10.

- "No. 25749". The London Gazette. 21 October 1887. p. 5653.

- Fifty Years in the Royal Navy, p. 61.

- Fifty Years in the Royal Navy, p. 61.

In those days "the Admiralty did not supply sufficient paint or cleaning material for keeping the ship up to the required standard, the officers had to find the money for buying the necessary housemaiding material." - "Right Honourable no more". BBC News.

- Kenneth Rose: King George V. Macmillan, 1983.

- Laß, Heiko; Seidel, Catrin; Krischke, Roland (2011). Schloss Friedenstein in Gotha mit Park (German). Stiftung Thüringer Schlösser und Gärten. ISBN 978-3-422-023437.

- Klüglein, Norbert (1991). Coburg Stadt und Land (German). Verkehrsverein Coburg.

- Beéche, Arthur E. The Coburgs of Europe. Eurohistory.com, 2014. p. 120 ISBN 978-0-9854603-3-4

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 18 March 2009. Retrieved 25 February 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

-

Reed, Alexander Wyclif (1975). Place Names of New Zealand. A. H. & A. W. Reed. p. 9. ISBN 9780589009335. Retrieved 31 July 2013.

After Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh, the second son of Queen Victoria. The Duke visited New Zealand in 1869 as a post captain in HMS Galatea, and twice in 1870.

- "Prince Alfred's Guard ceremony at newly-refurbished memorial". The Herald Online. Archived from the original on 15 November 2008.

- "Welcome to the Alfred Rowing Club site". Archived from the original on 16 April 2013. Retrieved 5 November 2008.

- The Commodore: Business Accommodation, Cape Town, South Africa(Legacy Hotels & Resorts International) Archived 4 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- "Prince Alfred Shellhole". Memorable Order of Tin Hats. Archived from the original on 15 May 2008.

- "Prince Alfred Pass". The Whale Rally. Archived from the original on 12 June 2009.

- Courtney, Nicholas (2004). The Queen's Stamps. ISBN 0-413-77228-4, pp. 28–29.

- As a son of the British monarch, he was styled His Royal Highness The Prince Alfred at birth

- Cokayne, G. E. (1890), Gibbs, Vicary (ed.), The complete peerage of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain and the United Kingdom, 3, London: St Catherine's Press, p. 234

- "Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh & Saxe-Coburg Gotha (1844–1900)". Archived from the original on 3 January 2008. Retrieved 29 September 2012.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- Shaw, Wm. A. (1906) The Knights of England, I, London, p. 62

- Shaw, p. 85

- Shaw, p. 104

- Shaw, p. 199

- Shaw, p. 309

- Shaw, p. 336

- Shaw, p. 401

- Shaw, p. 418

- "No. 26725". The London Gazette. 27 March 1896. p. 1960.

- Bragança, Jose Vicente de (2014). "Agraciamentos Portugueses Aos Príncipes da Casa Saxe-Coburgo-Gota" [Portuguese Honours awarded to Princes of the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha]. Pro Phalaris (in Portuguese). 9–10: 13. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- Staatshandbücher für das Herzogtum Sachsen-Coburg und Gotha (1865), "Herzogliche Sachsen-Ernestinischer Hausorden" p. 16

- Staatshandbuch für das Großherzogtum Sachsen / Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach (1869), "Großherzogliche Hausorden" p. 15

- Hof- und Staats-Handbuch des Großherzogtum Hessen (1879), "Großherzogliche Orden und Ehrenzeichen" pp. 11, 47

- Justus Perthes, Almanach de Gotha (1899) pp. 106–107

- Sergey Semenovich Levin (2003). "Lists of Knights and Ladies". Order of the Holy Apostle Andrew the First-called (1699–1917). Order of the Holy Great Martyr Catherine (1714–1917). Moscow.

- Staats- und Adreß-Handbuch des Herzogthums Nassau (1866), "Herzogliche Orden" p. 9

- Hof- und Staats-Handbuch des Großherzogtum Baden (1869), "Großherzogliche Orden" p. 55

- Hof- und Staats-Handbuch ... Baden (1868), "Großherzogliche Orden" p. 65

- M. & B. Wattel (2009). Les Grand'Croix de la Légion d'honneur de 1805 à nos jours. Titulaires français et étrangers. Paris: Archives & Culture. p. 460. ISBN 978-2-35077-135-9.

- "A Szent István Rend tagjai" Archived 22 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- Jørgen Pedersen (2009). Riddere af Elefantordenen, 1559–2009 (in Danish). Syddansk Universitetsforlag. p. 286. ISBN 978-87-7674-434-2.

- Acović, Dragomir (2012). Slava i čast: Odlikovanja među Srbima, Srbi među odlikovanjima. Belgrade: Službeni Glasnik. p. 607.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Per Nordenvall (1998). "Kungl. Maj:ts Orden". Kungliga Serafimerorden: 1748–1998 (in Swedish). Stockholm. ISBN 91-630-6744-7.

- Hof- und Staats-Handbuch des Königreich Württemberg (1896), "Königliche Orden" p. 28

- "Real y distinguida orden de Carlos III", Guóa Oficial de España (in Spanish), 1900, p. 174, retrieved 4 March 2019

- "Caballeros de la insigne orden del toisón de oro", Guóa Oficial de España (in Spanish), 1900, p. 167, retrieved 4 March 2019

References

- Heathcote, Tony (2002). The British Admirals of the Fleet 1734 – 1995. Pen & Sword Ltd. ISBN 0-85052-835-6.

- McKinlay, Brian The First Royal Tour, 1867–1868, (London: Robert Hale & Company, c1970, 1971) 200p. ISBN 0-7091-1910-0

- Sandner, H., Das Haus Sachsen-Coburg und Gotha, (Coburg: Neue Presse, 2001).

- Van der Kiste, John, & Jordaan, Bee Dearest Affie, (Gloucester: Alan Sutton, 1984)

- Van der Kiste, John Alfred, (Stroud: Fonthill Media, 2013)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Alfred, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. |

- "Assassination attempt on Prince Alfred 1868". Dictionary of Sydney. Dictionary of Sydney Trust. 2008. Retrieved 5 October 2015. [CC-By-SA]

Alfred, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha Cadet branch of the House of Wettin Born: 6 August 1844 Died: 30 July 1900 | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Ernest II |

Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha 1893–1900 |

Succeeded by Charles Edward |

| Military offices | ||

| Preceded by Sir Henry Bentinck |

Honorary Colonel of the 1st London Artillery Volunteer Corps 1868–1875 |

Office abolished |

| Preceded by Sir William Dowell |

Commander-in-Chief, Channel Fleet 1883–1884 |

Succeeded by Sir Algernon de Horsey |

| Commander-in-Chief, Plymouth 1890–1893 | ||

| Preceded by Lord John Hay |

Commander-in-Chief, Mediterranean Fleet 1886–1889 |

Succeeded by Sir Anthony Hoskins |