Japanese Surrendered Personnel

Japanese Surrendered Personnel (JSP) is a designation for captive Japanese soldiers (similar to Disarmed Enemy Forces and Surrendered Enemy Personnel). It was used in particular by British Forces referring to Japanese forces in Asia after the end of World War II.

Military and other labor

The concept of "Japanese Surrendered Personnel" was developed by the Japanese Government, and proposed to the Allies at the conclusion of World War II. The Japanese suggested this concept as the military's field service code and strong social norms prohibited military personnel, including senior officers, from being taken prisoner. The Allies accepted this proposal, as it was also advantageous to them even though the status lacked a legal basis.[1] JSP were not subject to the Prisoner of War Convention, and had no legal protections.[2]

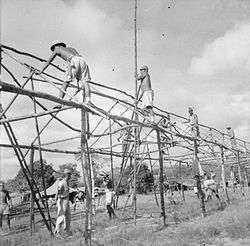

The JSP were until at least 1947 used for labor purposes, such as road maintenance, recovering corpses for reburial, cleaning, preparing farmland etc. Early tasks also included repairing airfields damaged by Allied bombing during the war and maintaining law and order until the arrival of the British forces of occupation.

After the war the U.K. quickly worked to regain control of its colonial empire territories, and also worked to ensure that the Dutch and French could regain control of their colonial empires. Due to British manpower shortages in the combat against the local resistance fighters who sought national independence, JSP were often pressed into combat service alongside British occupation troops. Louis Mountbatten took on 35,000 Japanese troops into his command in Indonesia. Retaining their wartime organisation and led by Japanese officers they had to fight alongside the British, with one Japanese even being recommended for the Distinguished Service Order as early as November 1945.[3] The recommendation was done by General Philip Christison for Japanese battalion commander Major Kido. Other examples of action include the Japanese company led by Captain Yamada that had to fight their way into Magelang to assist the British; Japanese Kempeitai (military police) used to guard camps in Buitenzorg, Japanese artillery units used for offensives in Bandung, and the Bandoeng garrison that was reinforced by 1,500 armed Japanese. Japanese saw action in Semarang, Ambarawa, Magelang.[4]

I of course knew that we had been forced to keep Japanese troops under arms to protect our lines of communication and vital areas...but it was nevertheless a great shock to me to find over a thousand Japanese troops guarding the nine miles of road from the airport to the town.[5]

Being aware of the sensitivity and hypocrisy of using Japanese troops for the purpose of by force restoring the European colonial Empires against the wishes of the people, the Americans and British worked successfully to conceal the extent of Japanese involvement in this post-war activity.[6]

"The retention of JSP by the British forces was carried out in spite of the repeated questioning of its validity by the American side."[5] However, at the same time that they questioned the British use of the JSP designation, the US made use of up to 80,000 JSP[7] in the Philippines for the duration of 1946, at one time even lowering the area priority for shipping and rerouting shipping to the British South East Asia Command to slow the rate of repatriation.[8]

Relevant publications

Several memoirs and other works relevant to the issue have been published. The most famous in Japan, which has been translated into English, is that by Aida Yuji, Prisoner of the British. A Japanese Soldier’s Experience in Burma.[9]

References

Citations

- Connor 2010, p. 395.

- Connor 2010, p. 398.

- Andrew Roadnight (2002), "Sleeping with the Enemy: Britain, Japanese Troops and the Netherlands East Indies, 1945–1946", History Volume 87 Issue 286.

- Richard McMillan, "The British occupation of Indonesia 194"

- "Japanese Prisoners of War" By Philip Towle, Margaret Kosuge, Yōichi Kibata. p. 146 (Google.Books)

- Andrew Roadnight, "Sleeping with the Enemy: Britain, Japanese Troops and the Netherlands East Indies, 1945–1946", History Volume 87 Issue 286.

- George G. Lewis and John Mewha, History of Prisoner of War Utilization by the United States Army, 1776–1945, Department of the Army Pamphlet No. 20-213, 1955. p. 257. Available at .

- Lewis and Mewha, pp. 259–260.

- Prisoner of the British. A Japanese Soldier’s Experience in Burma, trs.Hide Ishiguro, Louis Allen, Cresset Press, London 1966.

Works consulted

- Connor, Stephen (2010). "Side-stepping Geneva: Japanese Troops under British Control, 1945-7". Journal of Contemporary History. 45 (2): 389–405. JSTOR 20753592.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)