Nobusuke Kishi

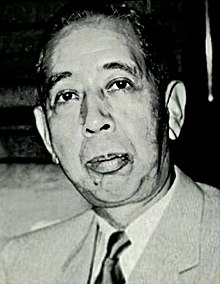

Nobusuke Kishi (岸 信介, Kishi Nobusuke, 13 November 1896 – 7 August 1987) was a Japanese politician who was Prime Minister of Japan from 1957 to 1960. He is the maternal grandfather of Shinzō Abe, twice prime minister from 2006–2007 and 2012–present.

Nobusuke Kishi | |

|---|---|

岸 信介 | |

| |

| Prime Minister of Japan | |

| In office 31 January 1957 – 19 July 1960 | |

| Monarch | Shōwa |

| Preceded by | Tanzan Ishibashi |

| Succeeded by | Hayato Ikeda |

| Director-General of the Japan Defense Agency | |

| In office 31 January 1957 – 2 February 1957 | |

| Prime Minister | Tanzan Ishibashi |

| Preceded by | Tanzan Ishibashi |

| Succeeded by | Akira Kodaki |

| Member of the House of Representatives | |

| In office 30 April 1942 – 7 October 1979 | |

| Constituency | Yamaguchi 1st |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 13 November 1896 Tabuse, Empire of Japan |

| Died | 7 August 1987 (aged 90) Tokyo, State of Japan |

| Political party | Liberal Democratic Party (1955–1987) |

| Other political affiliations |

|

| Spouse(s) | Ryoko

( m. 1919; died 1980) |

| Children | 3 |

| Alma mater | Tokyo Imperial University |

| Signature |  |

Known for his brutal rule of the Japanese puppet state Manchukuo in Northeast China, Kishi was called Shōwa no yōkai (昭和の妖怪; "Devil of Shōwa").[1] After World War II, Kishi was imprisoned for three years as a Class A war crime suspect. However, the U.S. government released him as they considered Kishi to be the best man to lead a post-war Japan in a pro-American direction. He went on to consolidate the Japanese conservative camp against perceived threats from the Japan Socialist Party in the 1950s, and is credited with being a key player in the initiation of the "1955 System", the extended period during which the Liberal Democratic Party was the overwhelmingly dominant political party in Japan.[2]

Early life and career

Kishi was born Nobusuke Satō in Tabuse, Yamaguchi Prefecture, but left his family at a young age to move in with the more affluent Kishi family, adopting their family name. Kishi was considered to be so brilliant as a boy that one of his uncles thought it better to adopt him as he believed that his nephew could do much to advance the interests of the Kishi family.[3] He attended an elementary school and middle school in Okayama, and then transferred to another middle school in Yamaguchi. His biological younger brother, Eisaku Satō, would also go on to become a prime minister. He is also the grandfather of the current prime minister of Japan Shinzō Abe. Kishi attended Tokyo Imperial University (now the University of Tokyo) and entered the Ministry of Commerce and Industry in 1920.[4] As a young man, Kishi was a follower of the Japanese fascist Ikki Kita whose writings called for a sort of monarchical socialism for Japan.[5]

Economic Manager of Manchukuo

In 1926-27, Kishi traveled around the world to study industry and industrial policy in various nations, such as the United States, Germany and the Soviet Union.[6] In 1929, he was deeply "shocked and impressed" with the Soviet first five-year plan, which left him a convinced believer in state-sponsored industrial development.[6] Besides for the Five Year Plan which left Kishi with an obsession with economic planning, Kishi was also greatly impressed with the labor management theories of Frederick Winslow Taylor in the United States, the German policy of industrial cartels and the high status of German technological engineers within the German business world.[7][6]

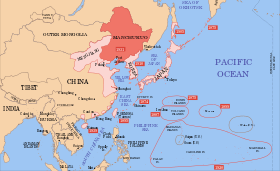

Kishi was one of the more prominent members of a group of "reform bureaucrats" within the Japanese government who favored an etatist model of economic development with the state guiding and directing the economy.[8] From 1933 onwards, Kishi regularly attacked democracy in his speeches and praised Nazi Germany as a model for Japan.[9] Very similar in their thinking as regards the "reform bureaucrats" in their plans to do away with laissez faire capitalism were the "total war" faction within the Imperial Japanese Army who wanted Japan to become a totalitarian "national defense state" whose economy would be geared entirely towards supporting the military.[10] In the early 1930s, Kishi forged an alliance between the "total war" school in the military and the "reform bureaucrats" in the civil service.[11] In September 1931, the Kwantung Army seized the Chinese region of Manchuria ruled by the warlord Zhang Xueliang, the "Young Marshal", and turned it into the nominally independent "Empire of Manchukuo" supposedly ruled by the Emperor Puyi. Manchukuo was a sham, and in reality it was a Japanese colony; Manchuko had all the trappings of a state, but it was not a real country.[11] All of the ministers in the Manchukuo government were Chinese or Manchus, but all of the deputy ministers were Japanese, and these were the men who really ruled Manchukuo. Kishi visited Manchukuo several times starting in the fall of 1931, where he quickly became friends with the leading officers in the Kwantung Army.[3] As an important bureaucrat in Tokyo, Kishi played a major role in forcing out the private shareholders in the South Manchuria Railway company, which was the largest corporation in Asia at the time, so that the Kwantung Army could become a shareholder instead.[3] One of Kishi's in-laws was the CEO of the South Manchuria Railroad, and his nephew advised him that making an alliance with the Kwantung Army was in the best interests of the corporation, and had the additional benefit of winning Kishi much goodwill from the officers of the Kwantung Army, who appreciated getting their share of the South Manchuria Railroad company's profits[3] Besides for the railroads, the South Manchuria Railroad company also owned oil fields, hotels, ports, telephone lines, mines and the telegraph lines in Manchuria, making it the dominant corporation in Manchuria.[3]

Right from the start, the Japanese Army planned to turn Manchukuo into the industrial powerhouse of the Japanese empire and carried out a policy of forced industrialization with a reckless disregard for human life; the model for Manchukuo was the Soviet First Five Year Plan.[11] Deeply distrustful of capitalism, the military completely excluded the Zaibatsu from investing in Manchukuo, and instead all of the industrial development of Manchuria was carried out by state-owned corporations.[11] Reflecting the military's ideas about the "national defense state", Manchukuo's industrial development was focused completely upon heavy industry such as steel production for the purposes of arms manufacture.[11] In 1935, Kishi was appointed Manchukuo's Deputy Minister of Industrial Development.[11] Kishi was given complete control of Manchukuo's economy by the military, with the authority to do whatever he liked just as long as industrial growth was increased.[12] After his appointment, Kishi persuaded the military to allow private capital into Manchukuo, successfully arguing that the military's policy of having the state-owned corporations leading Manchukuo's industrial development was costing the Japanese state too much money.[11] Kishi envisioned a "planned economy" for Manchukuo where bureaucrats such as himself would direct the zaibatsu into selected industries, which would create the necessary industrial basis for the "national defense state".[13] In place of the previous policy of "one industry, one firm" for Manchukuo, Kishi brought in a new policy of "all industries, one firm".[11] One of the zaibatsu that Kishi selected to invest in Manchukuo, the Nissan group, was headed by another of Kishi's uncles.[14] In order to make it profitable for the zaibatsu to invest in Manchukuo, Kishi had a policy of lowering the wages of the workers to the lowest possible point, even below the "line of necessary social reproduction" as he once put it.[15] The purpose of Manchukuo was to provide the industrial basis for the "national defense state" with Driscoll noting "Kishi's planned economy was geared towards production goals and profit taking, not competition with other Japanese firms; profit come primarily from rationalizing labor costs as much as possible. The nec plus ultra of wage rationalization would be withholding pay altogether-that is unremunerated forced labor."[16]

In 1935, he became one of the top officials involved in the industrial development of Manchukuo, where he was later accused of exploiting Chinese forced labor.[17] In 1935, Kishi introduced a Five Year Plan for Manchukuo, focusing on heavy industry intended to allow Japan to fight a "total war" with the Soviet Union or the United States by 1940.[18] Kishi spent almost all of his time in Manchukuo's capital, Hsinking (modern Changchun, China) with the exception of monthly trips to Dalian on the world famous Asia Express railroad line, where he indulged in his passion for women in alcohol- and sex-drenched weekends; one of Kishi's best friends later recalled that they never took their wives with them on their monthly trips to Dalian.[19] All of his friends in Manchukuo were Japanese and Kishi never associated with Chinese or any other ethnic groups in Manchuria on a social basis.[19] Kishi's dinner companions were fellow bureaucrats, businessmen seeking government contracts, Army officers and yakuza gangsters.[19] The presence of the latter was due to Kishi's involvement with the opium trade; the Manchukuo State Opium Monopoly needed distributors to move its products around the world, which in turn required contacts with the underworld in the form of the yakuza.[19] Additionally, Kishi used yakuza thugs to terrorize the Chinese workers in Manchukuo's factories into submission, and ensure that there were no strikes caused by the long hours, low pay and poor working conditions.[20] Because the plans of the Kwantung Army had always been to settle Manchukuo with millions of Japanese to solve the problem of overpopulation in Japan, and because of fears of unrest, the Kwantung Army generals had favored keeping the Han out of Manchukuo.[12] However, Kishi reversed these policies in 1935, arguing successfully to the generals that the yakuza would keep the Chinese workers in line and that to grow Manchukuo's industries required cheap Chinese labor to be exploited.[12] The American historians Sterling and Penny Seagrave wrote "...Kishi wove together the interests of politics, army, business and gangsters, in a way that would have deeply impressed Hitler and Stalin."[14]

As a self-described "playboy of the Eastern world", Kishi was known during his four years in Manchukuo for his lavish spending amid much drinking, gambling, and womanizing.[21] A man with a very active sex life, Kishi, when not visiting the brothels of Manchuria, was demanding sex from the waitresses who served him at the expensive restaurants he patronized, appearing to have regarded sex from waitresses as an essential part of his fine dining experience.[22] Kishi was able to afford his hedonistic, free-spending lifestyle as he had control over millions of yen with virtually no oversight, alongside being deeply involved in and profiting from the opium trade. As such, it is commonly believed that Kishi engaged in corruption partly in order to finance his own expensive taste.[23] Kishi was known for his skill in laundering money and as the man who could move millions of yen "with a single telephone call".[23] During his time in Manchukuo, Kishi was able to marshal private capital in a very strongly state-directed economy to achieve vastly increased industrial production while at the same time displaying complete indifference to the exploited Chinese workers toiling in Manchukuo's factories; the American historian Mark Driscoll described Kishi's system as a "necropolitical" system where the Chinese workers were literally treated as dehumanized cogs within a vast industrial machine.[24] Kishi favored giant conglomerates as the engines of industrial growth as the best way of achieving economics of scale. The system that Kishi pioneered in Manchuria of a state-guided economy where corporations made their investments on government orders later served as the model for Japan's post-1945 development, albeit not with same level of brutal exploitation as in Manchukuo.[25] Later on, Kishi's etatist model for economic development was adopted in South Korea and China, albeit not executed with anywhere near the same brutality as in Manchuria.[25]

In 1936, Kishi was one of the drafters of a proposed 3.13 billion yen Five Year Plan, which was intended to drastically increase industrial production both within Manchukuo and Japan itself to the point that Japan could fight a total war by 1941.[26] Kishi's "communistic" Five Year Plan created much opposition from the zaibatsu, who were not keen to see his statist Manchurian system extended to Japan; not the least because in Kishi's system, the purpose of private enterprise was to serve the state rather than make a profit, and in December 1936 following an extensive lobbying campaign by the industrialists, the Five Year Plan was rejected by the Imperial Diet.[27] However, the Five Year Plan, which rejected for Japan, went ahead in Manchukuo.[28] The intention of the Five Year Plan was to focus on heavy industry for military purposes and to vastly increase production of coal, steel, electricity and weapons.[28] One of the corporations founded for the Five Year Plan was the state-owned Manchurian Corporation for Development of Heavy Industry in 1937, which in its first year, had 5.2 billion yen invested in it by the Japanese state, making it by far the largest capital project in the Japanese empire; the total expenditure by the state for 1937 was 2.5 billion yen and for 1938 3.2 billion yen.[28] The Japanese historian Hotta Eri wrote that never before in Japanese history had the state ever embarked upon such a gigantic project such as the Five Year Plan.[28]

The Japanese conscripted hundreds of thousands of Chinese as slave labor to work in Manchukuo's heavy industrial plants. In 1937, Kishi signed a decree calling for the use of slave labour to be conscripted both in Manchukuo and in northern China, stating that in these "times of emergency" (i.e. war with China), industry needed to grow at all costs, and slavery would have to be used as the money to pay the workers was not there.[29] The American historian Mark Driscoll wrote that just as African slaves were taken to the New World on the "Middle Passage", it would be right to speak of the "Manchurian Passage" as vast numbers of Chinese peasants were rounded up to be taken as slaves to Manchukuo.[30] Starting in 1938 and continuing to 1945, about one million Chinese were taken every year to work as slaves in Manchukuo.[31] The harsh conditions of Manchukuo were well illustrated by the Fushun coal mine, which at any given moment had about 40,000 men working as miners, of whom about 25,000 had to be replaced every year as their predecessors had died due to poor working conditions and low living standards.[28]

A believer in the Yamato race theory, Kishi had nothing but contempt for the Chinese as a people, whom he disparagingly referred to as "lawless bandits" who were "incapable of governing themselves".[32] Precisely for these racist reasons, Kishi believed there was no point to establishing the rule of law in Manchukuo, as the Chinese were not capable of following laws, and instead brute force was what was needed to maintain social stability.[32] In Kishi's analogy, just as dogs were not capable of understanding abstract concepts such as the law, but could be trained to be utterly obedient to their masters, the same went with the Chinese, whom Kishi claimed were mentally closer to dogs than humans.[32] In this way, Kishi maintained that once the Japanese proved that they were the ones with the power, the dog-like Chinese would come to be naturally obedient to their Japanese masters, and as such the Japanese had to behave with a great deal of sternness to prove that they were the masters.[32] Kishi, when speaking in private, always used the term "Manchū" to refer to Manchukuo, instead of "Manchūkoku", which reflected his viewpoint that Manchukuo was not a state, but rather just a region rich in resources and 34 million people to be used for Japan's benefit.[32] In Kishi's eyes, Manchukuo and its people were literally just resources to be exploited by Japan, and he never made the pretense in private of maintaining Japanese rule was good for the people of Manchukuo.[29] Alongside the exploitation of men as slave workers went the exploitation of women as sex slaves, as women were forced into becoming "comfort women" as sexual slavery in the Imperial Army and Navy was called.[33] Kishi's racist and sexist views of Chinese and Korean women as simply "disposable bodies" to be used by Japanese men meant he had no qualms about rounding up women and girls to serve in the "comfort women corps".[34]

Tokyo's Pan-Asian rhetoric, where Manchukuo was a place where Manchus, Chinese, Japanese, Koreans, and Mongols would all to come together to live harmoniously in Pan-Asian peace, prosperity and brotherhood meant nothing to Kishi or the other Japanese bureaucrats governing Manchukuo. Along the same lines, Kishi used very dehumanizing language to describe the Chinese such as a people good for being only "robot slaves" or as a people who should be nothing more than "mechanical instruments of the Imperial Army, non-human automatons, absolutely obedient" to their Japanese masters.[32] One of Kishi's closest friends and business partners, the yakuza gangster Yoshio Kodama summed up his boss's thinking about the Chinese as: "We Japanese are like pure water in a bucket; different from the Chinese who are like the filthy Yangtze river. But be careful. If even the smallest amount of shit gets into our bucket, we become totally polluted. Since all the toilets in China empty into the Yangtze, the Chinese are soiled forever. We, however, must maintain our purity".[35] A recurring theme of Kishi's remarks was the Chinese were excrement, something dirty and disgusting, which he and other Japanese needed to maintain their "purity" from by avoiding as much as possible.[36]

Before returning to Japan in October 1939, Kishi is reported to have advised his colleagues in the Manchukuo government about corruption: "Political funds should be accepted only after they have passed through a 'filter' and been 'cleansed'. If a problem arises, the 'filter' itself will then become the center of the affair, while the politician, who has consumed the 'clean water', will not be implicated. Political funds become the basis of corruption scandals only when they have not been sufficiently 'filtered'."[23]

Minister in the Konoe and Tōjō governments

In 1940, Kishi became a minister in the government of Prince Fumimaro Konoe. Kishi intended to create within Japan the same sort of totalitarian "national defense state" that he had pioneered in Manchuria, but these plans ran into vigorous opposition from various vested interests.[37] In December 1940, Konoe dropped Kishi from his cabinet.[37] Prime Minister Hideki Tojo, himself a veteran of the Manchurian campaign, appointed Kishi Minister of Munitions in October 1941.[38] The mandate of the Tōjō government, provided by the Shōwa Emperor, was to prepare Japan for a war with the United States, and to this end Tōjō appointed Kishi to his cabinet as the best man to prepare Japan economically for the "total war" he had envisioned.[39] Tōjō regarded Kishi as his protege.[40] On 1 December 1941, Kishi voted in the Cabinet for war with the United States and Britain, and signed the declaration of war issued on 7 December 1941.[41] Kishi had known General Tōjō since 1931, and was one of his closest allies in the Cabinet. Kishi was also elected to the Lower House of the Diet of Japan in April 1942 as a member of the Imperial Rule Assistance Association.[23] As Munitions Minister, Kishi was deeply involved in taking thousands of Koreans and Chinese to work as slaves in Japan's factories and mines during the war.[42] During the war, 670,000 Koreans and 41,862 Chinese were taken to work as slave labor under the most degrading conditions in Japan; the majority did not survive the experience.[43] In July 1944, Kishi made the Tojo Cabinet resign en masse by forging disagreements within the Cabinet after the fall of Saipan. During the political crisis caused by the Japanese defeat at the Battle of Saipan, Tōjō attempted to save his government from collapse by reorganizing his cabinet, Kishi told Tōjō he only would resign if the prime minister resigned with the entire cabinet, saying a partial reorganization was unacceptable.[40] Firing Kishi was not an option since Tōjō himself had appointed him, and despite Tōjō's tears as he begged Kishi to save his government, Kishi was unmoved.[40] After the fall of the Tōjō government, he left the Imperial Rule Assistance Association and founded a new political party, the Kishi New Party.[23] Kishi took him with 32 members of the Diet into his party. The Kishi New Party was noteworthy because none of its members were connected to the zaibatsu; instead the Kishi New Party comprised small and middle-sized businessmen who had invested in Manchukuo during Kishi's time in Manchuria or who had benefited from state contracts during Kishi's time as Munitions Minister; senior executives at the "public policy corporations" Kishi had created for investments in Manchukuo, and ultra-nationalists who had participated in coup attempts in the 1930s.[23]

Prisoner of Sugamo

After the Japanese surrender to the Allies in August 1945, Kishi, with other members of the former Japanese government, was held at Sugamo Prison as a "Class A" war crimes by the order of the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers. The womanizing Kishi found the forced celibacy of prison life the most difficult aspect of being held in Sugamo as he was held alone in his cell; Kishi, who was used to having sex dozens of times every day, found the absence of women very hard to cope with.[22] During his time as a prisoner, Kishi fondly remembered his womanizing days in Manchuria in the 1930s, where he recalled: "I came so much, it was hard to clean it all up".[22] During this time, a group of influential Americans who had formed themselves into the American Council on Japan came to Kishi's aid, and lobbied the American government to release him as they considered Kishi to be the best man to lead a post-war Japan in a pro-American direction.[42] The American Council on Japan comprised the journalists Harry Kern and Compton Packenham, the lawyer James L. Kauffman, former Ambassador Joseph C. Grew, and former diplomat Eugene Dooman.[42] Unlike Hideki Tōjō (and several other Cabinet members), however, Kishi was released in 1948 and was never indicted or tried by the International Military Tribunal for the Far East. However, he remained legally prohibited from entering public affairs because of the Allied occupation's purge of members of the old regime. In his prison diary, Kishi rejected the legitimacy of the American war crimes trials, which he called a "farce", and Kishi would spend the rest of his life working for the rehabilitation of all the war criminals convicted by the Allies after 1945.[44] During his time as a prisoner, Kishi had already begun plotting his political comeback. He conceived of the idea of a mass party uniting the more moderate socialists and conservatives into a "popular movement of national salvation", a populist party that would use statist methods to encourage economic growth and would mobilize the entire nation in support of its nationalist policies.[23]

Post-WWII political career

When the prohibition on former government members was fully rescinded in 1952 with the end of the Allied occupation of Japan, Kishi was central in creating the "Japan Reconstruction Federation" (Nippon Saiken Renmei). Besides for becoming Prime Minister, Kishi's main aim in politics was revise the American-imposed constitution, especially Article 9.[23] In a speech, he called for doing away with Article 9, saying if Japan were to become a: "respectable member (of) the community of nations it would first have to revise its constitution and rearm: If Japan is alone in renouncing war ... she will not be able to prevent others from invading her land. If, on the other hand, Japan could defend herself, there would be no further need of keeping United States garrison forces in Japan. ... Japan should be strong enough to defend herself."[23] Kishi's Japan Reconstruction Federation fared disastrously in the 1952 elections, and Kishi failed in his bid to be elected to the Diet.[23] After that defeat, Kishi disbanded his party, and tried to join the Socialists; after being rebuffed, he reluctantly joined the Liberal Party instead.[23] After being elected to the Diet as a Liberal in 1953, Kishi's main activities were undermining the leadership of the Liberal leader, Shigeru Yoshida so he could become the Liberal leader in his place.[23] Kishi's main avenues of attack were that Yoshida was far too deferential to the Americans and for the need to do away with Article 9.[23] In April 1954 Yoshida expelled Kishi for his attempts to depose him as Liberal leader.[23] By this time, the very wealthy Kishi had well over 200 members of the Diet as his loyal followers.[23] In November 1954, Kishi took his faction into Democratic Party led by Ichirō Hatoyama. Hatoyama was the party leader, but Kishi was the party-secretary, and crucially he controlled the party's finances, which thus made him the dominant force within the Democrats.[23] Elections in Japan were very expensive, so few candidates to the Diet could afford the costs of an election campaign out of their own pockets or could fund-raise enough money for a successful bid for the Diet. As a result, candidates to the Diet needed a steady infusion of money from the party-secretariat to run a winning campaign, which made Kishi a powerful force within the Democratic Party as he determined which candidates received money from the party-secretariat and how much.[23] As a result, Democratic candidates for the Diet either seeking election for the first time or reelection were constantly seeing Kishi to seek his favor. Reflecting Kishi's power as party-secretary, Hatoyama was described as an omikoshi, a type of portable Shinto shrine carried around to be worshipped.[23] Everyone bows downs and worships an omikoshi, but to move an omikoshi must be picked up and carried by somebody.

In February 1955, the Democrats won the general elections. On the day after Hatoyama was sworn in as prime minister, Kishi began talks with the Liberals about merging the two parties now that his arch-enemy Yoshida had stepped down as Liberal leader after losing the elections.[23] In November 1955, the Democratic Party and Liberal Party merged to elect Ichirō Hatoyama as the head of the new Liberal Democratic Party. Within the new party, Kishi once again become the party-secretary with control of the finances.[23] Kishi had reassured the American ambassador John Allison that "for the next twenty five years it would be in Japan's best interests to cooperate closely with the United States."[42] The Americans wanted Kishi to become Prime Minister and were disappointed when Tanzan Ishibashi, the most anti-American of the LDP politicians won the party's leadership, leading an American diplomat to write the U.S had bet its "money on Kishi, but the wrong horse won."[42] Two prime ministers later, in 1957, Kishi was voted in following the resignation of the ailing Tanzan Ishibashi.

In February 1957, Kishi become Prime Minister. His main concerns were with foreign policy, especially with revising the 1952 U.S-Japan Security Treaty, which he felt had turned Japan into a virtual American protectorate.[45] Revising the security treaty was understood to be the first step towards his ultimate goal of abolishing Article 9. Besides his desire for a more independent foreign policy, Kishi wanted to establish close economic relations with the nations of South-East Asia to create a Japanese economic sphere of influence, which might one day become a political sphere of influence as well.[45] Finally, Kishi wanted the Allies to free all of the Class B and Class C war criminals still in serving their prison sentences, arguing that for Japan to play its role in the Cold War as a Western ally required forgetting about Japan's war crimes in the past.[45]

In the first year of Kishi's term, Japan joined the United Nations Security Council, paid reparations to Indonesia, signed a new commercial treaty with Australia, and signed peace treaties with Czechoslovakia and Poland. In 1957, Kishi presented a plan for a Japanese-dominated Asian Development Fund (ADF), which was to operate under the slogan "Economic Development for Asia by Asia", calling for Japan to invest millions of yen in Southeast Asia.[46] For most Japanese Asia had meant Korea and China, especially Manchuria, but in the 1950s, Korea and China were off fines.[47] Japan did not have diplomatic relations with South Korea until 1964 when the South Korean dictator General Park Chung-hee who had served as an officer with the Manchukuo Army in World War II established relations and even then, it caused riots in South Korea. Japanese relations with North Korea and China in the 1950s were even worse.[47] For all these reasons, Kishi turned towards Southeast Asia as an alternative market for Japanese goods and a source of raw materials.[47] Additionally, the Americans wanted more aid to Asia to spur economic growth that would stem the appeal of Communism, but the Americans were disinclined to spend the money themselves.[48] The prospect of Japan spending some $500 million US in low interest loans and aid projects in Southeast Asia had the benefit from Kishi's viewpoint of improving his standing in Washington, and giving him more leverage in his talks to revise the U.S-Japan Security Treaty.[49] In 1957 Kishi was also Director General of the Japan Defense Agency.

In pursuit of the ADF, Kishi visited India, Pakistan, Burma, Thailand, Ceylon, and Taiwan in May 1957, asking the leaders of those nations to join the ADF, but with the exception of Taiwan, which agreed to join, all of the leaders of the those nations gave equivocal answers.[50] Through he always denied it in public, but Kishi saw the ADF as an economic version of the "Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere" that Japan had sought to establish in World War II, which contributed to the failure of the proposed ADF as memories of the Japanese occupation were too fresh in Southeast Asia.[51] To many people in Southeast Asia, the slogan "Economic Development for Asia by Asia" sounded too much like the wartime Japanese slogan "Asia for Asians!".[51] During World War II, the Japanese state had always presented the war as a race war between Asians vs. the "white devils", portraying the war as a Pan-Asian crusade to unite all of the peoples of Asia against the "white devils".[52] The Japanese had been welcomed as liberators from European imperialism in some countries when they arrived in Southeast Asia, but soon the peoples of Southeast Asia had learned the Japanese did not regard other Asians as equals, as the Japanese had a habit of slapping the faces of the peoples they ruled to remind them who were the "Great Yamato race" and who were not.[52] The Burmese Prime Minister U Nu had, like everyone else in the Burmese elite, been a Japanese collaborator in World War II. Precisely because of his past U Nu told Kishi during his visit to Rangoon that he was reluctant to join the ADF as it would remind the Burmese people of the days when he was shouting Pan-Asian rhetoric, praising Japan as the natural leader of Asia and declaring how happy he was to serve the Japanese.[53] Even in countries that were not occupied by Japan like India, Ceylon and Pakistan, Kishi encountered obstacles. During his visit to Karachi, the Pakistani Prime Minister Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy told Kishi that he thought of himself as a "human being rather than an Asian first", preferred bilateral over multilateral aid as it allowed Pakistan to play off rival nations for better terms, and that Pakistan would not join the ADF if India also joined.[54] Suhrawadry made it clear that until the Kashmir dispute was settled to Pakistan's satisfaction that Pakistan would not be joining any organization that India was a member of.[55] The Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru told Kishi during his visit to New Delhi that he wanted his nation to be neutral in the Cold War, and that as Japan was allied to the United States, joining the ADF would be in effect aligning India with the Americans.[54] In Colombo, the Ceylonese Prime Minister S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike, through not objecting to the ADF in principle, told Kishi that he preferred bilateral aid deals as it allowed Ceylon to play off the Soviet Union against the United States, and objected to the provision that joining the ADF would mean be "locked in" to only accepting aid from the ADF.[56] Only during his visit to Taiping did Kishi receive outright acceptance of the ADF, through the Taiwanese press statement proclaiming the ADF would be most useful for stopping the rise of Communism in Asia proved embarrassing for Kishi as he had maintained in public that the ADF was supposed to be an organization for allowing Asians to help other Asians and had nothing to do with the Cold War.[57] Because Japan was a much richer nation than all of the other nations of the proposed ADF combined, the ADF was generally as a vehicle for Japan to re-establish itself as a great power in Asia, as few had any doubt that Japan would be the dominant member of the ADF.[58] Moreover, the fact that the United States was supporting the ADF led the proposed organization to be seen as siding with the United States in the Cold War, a struggle that many Asian nations wanted to be neutral in.[59]

Kishi's next foreign policy initiative was much more difficult: reworking Japan's security relationship with the United States. With this in mind, Kishi wanted to revise Articles 1 and 9 of the 1947 American-imposed constitution to allow Japan to allow the Emperor to play a more active political role and for Japan to have the freedom to once again wage war.[45] In June 1957, Kishi visited the United States, where he was received with honor, being allowed to address a joint session of Congress, throwing the opening pitch for the New York Yankees in a baseball game in New York and being allowed to play golf at an otherwise all-white golf club in Virginia, which the American historian Michael Schaller called "remarkable" honors for a man who as a Cabinet minister had signed the declaration of war against the United States in 1941 and who was responsible for using thousands of Koreans and Chinese as slave labor during World War II.[42] The Vice President of the United States, Richard Nixon introduced Kishi to Congress as a "honored guest who was not only a great leader of the free world, but also a loyal and great friend of the people of the United States", apparently unaware or indifferent to the fact that Kishi had been one of the closest associates of General Tojo, hanged by the United States for war crimes in 1948.[23]

In November 1957, Kishi laid down his proposals for a revamped extension of the US–Japan Mutual Security Treaty. The American ambassador Douglas MacArthur II reported to Washington that Kishi was the most pro-American of the Japanese politicians, and if the U.S refused to revise the security treaty in Japan's favor, he would be replaced as Prime Minister by a more anti-American figure.[42] The U.S. Secretary of State, John Forster Dulles wrote in a memo to President Eisenhower that the United States was "at the point of having to make a Big Bet" in Japan and Kishi was the "only bet we had left in Japan".[42] Anticipating public opposition to his plans for revising the security treaty, Kishi also brought before the Diet a harsh bill giving the police vastly new powers to crush demonstrations and to conduct searches of homes without warrants.[45][23] In response to the police bill, the Sōhyō union federation went on a general strike with the aim of killing the police bill.[60] The strike achieved its goal, and Kishi withdrew the police bill.[23] In February 1958, when the Indonesian president Sukarno visited Japan, the Tokyo police refused to provide security under the grounds that this was a private visit, not a state one.[23] At that point, Kishi asked for one of his close friends, the Yakuza gangster Yoshio Kodama to provide thugs from the underworld for Sukarno's protection.[23] Sukarno, like other anti-Western nationalists in South-East Asia had welcomed the Japanese as liberators from the Europeans, in his case the Dutch during World War II, embracing Tokyo's Pan-Asian message of "Asia for Asians" as his own, serving in a Japanese puppet government, and given this background was very pro-Japanese. During Sukarno's visit, Kishi negotiated a reparations agreement with Indonesia, where Japan agreed to provide compensation for war-time suffering.[23] Kishi's reasons for paying reparations to Indonesia had less to do with guilt over the Japanese occupation and more to do with the chances to engage in questionable contracts to reward his friends as Kishi insisted that Japan would only pay reparations in the form of goods, not money.[23] In April 1958, Kishi told the Indonesian Foreign Minister Soebandrio that he wanted Indonesia to ask to receive reparations in the form of ships built exclusively by the Kinoshita Trading Company-which happened to be run by Kinoshita Shigeru, a metal merchant and an old friend of Kishi's from their Manchurian days in the 1930s-even through the Kinoshita company had never built ships before, and there were many other well-established Japanese shipbuilders who could have provided ships at a lower price.[23] All of the reparations contracts to the nations of South-East Asia during Kishi's time as Prime Minister went to firms run by businessmen who were closely associated with him during his time in Manchuria in the 1930s.[23] Additionally, there were frequent claims that when came time to award reparations contracts that high-ranking Indonesian politicians had to receive kickbacks, and that ordinary Indonesians never received any benefits from the reparations.[23] During the same period, there were questions about the M-fund, a secret American fund intended to stabilize Japan economically.[23] The American Assistant Attorney General Norbert Schlei alleged that starting in 1957: "Beginning with Prime Minister Kishi, the Fund has been treated as a private preserve of the individuals into whose control it has fallen. Those individuals have felt able to appropriate huge sums from the Fund for their own personal and political purposes ... The litany of abuses begins with Kishi who, after obtaining control of the fund from (then Vice President Richard) Nixon, helped himself to a fortune of one trillion yen ... Kakuei Tanaka, who dominated the Fund for longer than any other individual, took from it personally some ten trillion yen ... Others who are said to have obtained personal fortunes from the Fund include Mrs. Eisaku Sato ... and Masaharu Gotoda, a Nakasone ally and former chief cabinet secretary."[23]

On 27 November 1958, over the opposition of the Emperor, Crown Prince Akihito announced his engagement to Shōda Michiko, which marked the first time that a member of the House of Yamato had married a commoner or had married for love.[61] For the Japanese people, the idea that a member of the Imperial family would marry a commoner for love was revolutionary as such thing had never happened in Japan before, and the marriage proved very popular with the public.[62] In February 1959, a public opinion showed 87% of the Japanese people approved of Akihito's choice of bride.[60] The Shinto clergy disapproved of the wedding because Michiko was a Roman Catholic while traditionalists in general led by the Emperor himself were opposed to the idea of the Crown Prince marrying a commoner for love as this was out of line with Japanese tradition, but given the level of public support, there was nothing to be done to stop the wedding.[63] Kishi saw the Imperial wedding as a chance to divert attention from the unpopular security treaty, and gave his approval to the engagement.[60] As the nation was caught in Imperial wedding fever, the issue of the security treaty vanished and Kishi mistakenly assumed the matter was over.[64] On 10 April 1959, before a TV audience of 15 million people, Crown Prince Akihito married Michiko while half-million people showed up to watch the wedding in person.[60] After the wedding, the matter of the security treaty returned to the public mind while Kishi thought the public had forgotten about the treaty.[65] At the same time, right-wing terrorism which had flourished in the 1930s returned to Japan.[66] The prospect of the children of a commoner sitting one day on the Chrysanthemum Throne energized the far-right in Japan, and left-wing opponents of the revised security treaty were threatened and sometimes assassinated.[66] The most brutal killing of the 1958-61 terrorist campaign occurred when Inejiro Asanuma, leader of the Socialist Party, was killed while giving a speech on live television by a right-wing fanatic who stabbed him to death with his samurai sword.[66] Kishi does seem not to have ordered the killings, but he fostered a climate of opinion when anyone who criticized his government was seen as a traitor, and the police proved remarkably ineffective at stopping the far-right in their campaign of intimation and assassination against critics of the Kishi government.[66] In July–August 1959, Kishi visited Western Europe and South America.

After closing the discussion and vote without the opposition group in the Diet of Japan, concerning his plans for a revised Security treaty in early 1960, demonstrators clashed with police in Nagatachō, at the steps of the National Diet Building. About 500 people were injured in the first month of demonstrations. Despite their magnitude, Kishi did not think much of the demonstrations, referring to them as "distasteful" and "insignificant". [67] Once the protests died down, Kishi went to Washington, and in January 1960 returned to Japan with a new and unpopular Treaty of Mutual Cooperation. On 19 January 1960 Kishi signed a new treaty with the U.S, which provided Japan with more power than the 1952 treaty, but was very unpopular with the Japanese public, who saw the treaty as allowing for Japan to once become involved in a war.[65] During his visit to the United States, Kishi appeared on the cover of Time on 25 January 1960, which declared that the Prime Minister's "134 pound body packed pride, power and passion--a perfect embodiment of his country's amazing resurgence" while Newsweek called him the "Friendly, Savvy Salesman from Japan" who had created the "economic powerhouse of Asia".[42] Demonstrations, strikes and clashes continued as the government pressed for ratification of the treaty. During this time, Kishi once again called upon the services of Kodama, who was asked to send his thugs out to beat up the demonstrators, a request that was granted.[23]

When Kishi submitted the treaty to the Diet for ratification on 19 May 1960, such were the demonstrations against the treaty that 500 policemen had to assembled outside the Diet while Kishi made the treaty a confidence vote in his government, thereby forcing the LDP Dietmen to vote for the treaty if they did not want the government to fall.[65] On June 10, White House Press Secretary James Hagerty arrived in preparation for a state visit of President Dwight Eisenhower. He was met at the airport by Ambassador Douglas MacArthur II. Knowing that leftist demonstrators lined the road from the airport they chose to travel by car rather than helicopter. They felt that if the demonstrators were going to resort to violence it would be better for both the US and Japanese governments to know rather than waiting to test their resolve at the arrival of the President. They also believed that if any violence ensued it would bias the Japanese populace against the demonstrators. As they approached the exit to the airport grounds a mob spearheaded by Zengakuren students closed in stoning the car, shattering windows, slashing tires, and trying to overturn them. Police reached them after 15 minutes and managed to clear a landing zone for a helicopter which transported them the rest of the way.[68] On 15 June 1960 a university student protesting against the treaty outside the Diet was killed by the police, which led to the largest demonstrations ever in Japanese history, both against police brutality and the treaty.[65] To his embarrassment, Kishi had to request the postponement of Eisenhower's state visit. The end of Eisenhower's term of office prevented it from being rescheduled. The loss of face this entailed, along with his apparent inability to restrain the demonstrations resulted in factional disputes within the Liberal Democratic Party. The Emperor had wanted to greet President Eisenhower when he landed in Japan, and was displeased about the cancellation of the president's trip, which for a politician like Kishi who had wanted to restore to the Emperor his political powers was highly embarrassing.[69] Kishi had the treaty ratified, but he had used up so much political capital and his government had become so unpopular that all the LDP factions united to demand that he resign.[69] Kishi's plans to repeal Article 9 of the constitution were even more unpopular than the security treaty, and given the extent of popular opposition to the security treaty, to attempt to repeal Article 9 as Kishi wanted was seen as political suicide within the LDP.[69] In April 1960, across the Korea straits, the South Korean president Syngman Rhee was overthrown in the April Revolution-which was led by protesting university students-and at the time, there was serious fears in Japan that protests led by university students against the Kishi government might likewise lead to a revolution, making it imperative to ditch the very unpopular Kishi.[69] On 15 July 1960 Kishi resigned and Hayato Ikeda became prime minister.

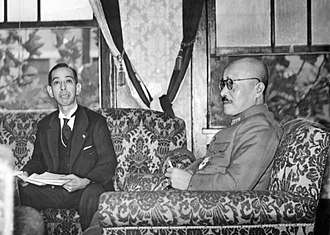

After taking power in a coup d'etat in May 1961, the South Korean dictator General Park Chung-hee visited Japan in November 1961 to discuss establishing diplomatic relations between Japan and South Korea, which were finally achieved in 1965.[70] Park had been a Japanese collaborator, serving in the Manchukuo Army and had fought with the Kwantung Army against the "bandits" as the Japanese called all guerrillas in Manchuria. During his visit to Japan, Park met with Kishi, where speaking in his fluent, albeit heavily Korean accented Japanese, praised Japan for its colonial rule in both Korea and Manchukuo, saying that his training by the Japanese Army had taught him the "efficiency of the Japanese spirit", and that he wanted to learn "good plans" from Japan for South Korea.[70] Besides for fond reminiscences about the Japanese officers in Manchukuo who taught him about how to give a "good thrashing" to one's opponents, Park was very interested in Kishi's economic policies in Manchuria as a model for South Korea.[70] Kishi told the Japanese press about his meeting with Park that he was a "little embarrassed" by Park's rhetoric, which was virtually unchanged from the sort of talk used by Japanese officers in World War II with none of the concessions to the world of 1961 that Kishi himself employed.[70] During his time as president of South Korea, Park launched the Six-Year Plans for the economic development of South Korea that featured much etatist economic policies that very closely resembled Kishi's Five Year Plans.[70] In 1965, Kishi gave a speech where he called for Japanese rearmament as "a means of eradicating completely the consequences of Japan's defeat and the American occupation. It is necessary to enable Japan finally to move out of the post-war era and for the Japanese people to regain their self-confidence and pride as Japanese."[71] Kishi always saw the system created by the Americans as temporary and intended that one day Japan would resume its role as a great power; in the interim, he was prepared to work within the American-created system both domestically and internationally to safeguard what he regarded as Japan's interests.[71]

On 14 December 2006, Manmohan Singh, the Prime Minister of India, made a speech in the Diet of Japan. He stated, "It was Prime Minister Kishi who was instrumental in India being the first recipient of Japan's ODA. Today India is the largest recipient of Japanese ODA and we are extremely grateful to the government and people of Japan for this valuable assistance."[72]

Controversies

Kishi illustrates the ambivalent role of America in post-war Japan,[73] and the difficulty of eradicating nationalist World War II revisionism from a postwar Japan where associated political dynasties remained entrenched. As prime minister, Kishi's own legacy was ambivalent: on the one hand he worked for international peace, but on the other he promoted postwar nationalist revisionism by liberating former military personnel convicted by the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers of various war crimes, and dedicating on Mount Sangane a headstone to General Tojo and six other military leaders executed after the Tokyo war crimes trial, marking their grave as that of "the seven patriots who died for their country".[74]

Kishi's role in the late 1950s was to consolidate the conservative camp against perceived threats from the Japan Socialist Party. He is credited with being a key player in the initiation of the "1955 System": the extended period during which the LDP was the overwhelmingly dominant political party in Japan. His actions have been described as originating the most successful money-laundering operation in the history of Japanese politics.[2]

He served as Japan's official representative at the funeral of Sir Winston Churchill in 1965. He had visited Churchill in London six years before the latter's death.

Honours

From the corresponding article in the Japanese Wikipedia

- Coronation Medal (10 November 1928)

- Order of the Sacred Treasure, 5th Class (April 1934)

- Military Medal of Honor (April 1934)

- Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun with Paulownia Flowers (29 April 1967)

- United Nations Peace Medal (with Ryōichi Sasakawa) (1979)

- Grand Cordon of the Order of the Chrysanthemum (7 August 1987; posthumous)

Order of precedence

- Senior second rank (August 1987; posthumous)

- Senior third rank (July 1960)

- Fourth rank (October 1940)

- Senior fifth rank (September 1934)

- Fifth rank (September 1929)

- Senior sixth rank (September 1927)

- Sixth rank (August 1925)

- Senior seventh rank (October 1923)

- Seventh rank (May 1921)

Foreign Honours

.svg.png)

Descendants

Shintarō Abe was Kishi's son-in-law, and his son Shinzō Abe, the current prime minister of Japan, is Kishi's grandson.

References

- Richard J. Samuels (2005). Machiavelli's Children: Leaders and Their Legacies in Italy and Japan. Cornell University Press. pp. 441–. ISBN 0-8014-8982-2.

- "Kishi and Corruption: An Anatomy of the 1955 System", Japan Policy Research Institute Working Paper No. 83, December 2001.

- Seagrave, Sterling & Seagrave, Penny The Yamato Dynasty, New York: Broadway Books, 1999 page 270.

- Maiolo, Joseph Cry Havoc How the Arms Race Drove the World to War, 1931–1941, New York: Basic Books, 2010 page 29.

- Driscoll, Mark Absolute Erotic, Absolute Grotesque: The Living, Dead, and Undead in Japan's Imperialism, 1895–1945 Durnham: Duke University Press, 2010 pages 255

- Maiolo, Joseph Cry Havoc How the Arms Race Drove the World to War, 1931-1941, New York: Basic Books, 2010 pages 29–30.

- Driscoll, Mark Absolute Erotic, Absolute Grotesque: The Living, Dead, and Undead in Japan's Imperialism, 1895–1945 Durnham: Duke University Press, 2010 pages 267-268

- Maiolo, Joseph Cry Havoc How the Arms Race Drove the World to War, 1931-1941, New York: Basic Books, 2010 pages 29

- Driscoll, Mark Absolute Erotic, Absolute Grotesque: The Living, Dead, and Undead in Japan's Imperialism, 1895–1945 Durnham: Duke University Press, 2010 page 269

- Maiolo, Joseph Cry Havoc How the Arms Race Drove the World to War, 1931-1941, New York: Basic Books, 2010 pages 28-29

- Maiolo, Joseph Cry Havoc How the Arms Race Drove the World to War, 1931-1941, New York: Basic Books, 2010 page 30

- Driscoll, Mark Absolute Erotic, Absolute Grotesque: The Living, Dead, and Undead in Japan's Imperialism, 1895–1945 Durnham: Duke University Press, 2010 page 273.

- Maiolo, Joseph Cry Havoc How the Arms Race Drove the World to War, 1931-1941, New York: Basic Books, 2010 page 30.

- Seagrave, Sterling & Seagrave, Penny The Yamato Dynasty, New York: Broadway Books, 1999 page 271.

- Driscoll, Mark Absolute Erotic, Absolute Grotesque: The Living, Dead, and Undead in Japan's Imperialism, 1895–1945 Durnham: Duke University Press, 2010 pages 269

- Driscoll, Mark Absolute Erotic, Absolute Grotesque: The Living, Dead, and Undead in Japan's Imperialism, 1895–1945 Durnham: Duke University Press, 2010 page 274.

- Dower, John (2000). Embracing Defeat. W. W. Norton and Company. p. 454.

- Driscoll, Mark Absolute Erotic, Absolute Grotesque: The Living, Dead, and Undead in Japan's Imperialism, 1895–1945 Durnham: Duke University Press, 2010 page xv

- Driscoll, Mark Absolute Erotic, Absolute Grotesque: The Living, Dead, and Undead in Japan's Imperialism, 1895–1945 Durnham: Duke University Press, 2010 page 267.

- Driscoll, Mark Absolute Erotic, Absolute Grotesque: The Living, Dead, and Undead in Japan's Imperialism, 1895–1945 Durnham: Duke University Press, 2010 page 270.

- Driscoll, Mark Absolute Erotic, Absolute Grotesque: The Living, Dead, and Undead in Japan's Imperialism, 1895–1945 Durnham: Duke University Press, 2010 page 277

- Driscoll, Mark Absolute Erotic, Absolute Grotesque: The Living, Dead, and Undead in Japan's Imperialism, 1895–1945 Durnham: Duke University Press, 2010 page 267

- Samuels, Richard (December 2001). "Kishi and Corruption: An Anatomy of the 1955 System". Japan Policy Research Institute. Retrieved 2015-09-09.

- "The Unquiet Past Seven decades on from the defeat of Japan, memories of war still divide East Asia". The Economist. 12 August 2015. Retrieved 2015-09-09.

- "The Unquiet Past Seven decades on from the defeat of Japan, memories of war still divide East Asia". The Economist. 12 August 2015. Retrieved 2015-09-09.

- Maiolo, Joseph Cry Havoc How the Arms Race Drove the World to War, 1931-1941, New York: Basic Books, 2010 page 36

- Maiolo, Joseph Cry Havoc How the Arms Race Drove the World to War, 1931–1941, New York: Basic Books, 2010 pages 36–37

- Hotta, Eri Pan-Asianism and Japan's War 1931-1945, London: Palgrave, 2007 page 125.

- Driscoll, Mark Absolute Erotic, Absolute Grotesque: The Living, Dead, and Undead in Japan's Imperialism, 1895–1945 Durnham: Duke University Press, 2010 page 275

- Driscoll, Mark Absolute Erotic, Absolute Grotesque: The Living, Dead, and Undead in Japan's Imperialism, 1895–1945 Durnham: Duke University Press, 2010 page xii

- Driscoll, Mark Absolute Erotic, Absolute Grotesque: The Living, Dead, and Undead in Japan's Imperialism, 1895–1945 Durnham: Duke University Press, 2010 page 276.

- Driscoll, Mark Absolute Erotic, Absolute Grotesque: The Living, Dead, and Undead in Japan's Imperialism, 1895–1945 Durnham: Duke University Press, 2010 page 266

- Driscoll, Mark Absolute Erotic, Absolute Grotesque: The Living, Dead, and Undead in Japan's Imperialism, 1895–1945 Durnham: Duke University Press, 2010 page 307

- Driscoll, Mark Absolute Erotic, Absolute Grotesque: The Living, Dead, and Undead in Japan's Imperialism, 1895–1945 Durnham: Duke University Press, 2010 pages 307-308

- Driscoll, Mark Absolute Erotic, Absolute Grotesque: The Living, Dead, and Undead in Japan's Imperialism, 1895–1945 Durnham: Duke University Press, 2010 page 280

- Driscoll, Mark Absolute Erotic, Absolute Grotesque: The Living, Dead, and Undead in Japan's Imperialism, 1895–1945 Durnham: Duke University Press, 2010 page 279.

- Maiolo, Joseph Cry Havoc: How the Arms Race Drove the World to War, 1931–1941, New York: Basic Books, 2010 page 390.

- Buruma, Ian. Year Zero: A History of 1945 (p. 187). Penguin Group US. Kindle Edition.

- Maiolo, Joseph Cry Havoc How the Arms Race Drove the World to War, 1931-1941, New York: Basic Books, 2010 page 395.

- Browne, Courtney Tojo The Last Banzai, Boston: Da Capo Press, 1998 page 179.

- Bix, Herbert Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan, New York: Perennial, 2001 page 634

- Schaller, Michael (July 11, 1995). "America's Favorite War Criminal: Kishi Nobusuke and the Transformation of U.S.-Japan Relations". Japan Policy Research Institute. Retrieved 2015-09-09.

- Dower, John War Without Mercy: Race & Power in the Pacific War, New York: Pantheon 1993 page 47

- Bix, Herbert Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan, New York: Perennial, 2001 page 612

- Bix, Herbert Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan, New York: Perennial, 2001 page 660

- Hoshiro, Hiroyuki "Co-Prosperity Sphere Again? United States Foreign Policy and Japan's "First" Regionalism in the 1950s" pages 385-405 from Pacific Affairs, Volume 82, Issue #3, Fall 2009 page 398.

- Hoshiro, Hiroyuki "Co-Prosperity Sphere Again? United States Foreign Policy and Japan's "First" Regionalism in the 1950s" pages 385-405 from Pacific Affairs, Volume 82, Issue #3, Fall 2009 page 387.

- Hoshiro, Hiroyuki "Co-Prosperity Sphere Again? United States Foreign Policy and Japan's "First" Regionalism in the 1950s" pages 385-405 from Pacific Affairs, Volume 82, Issue #3, Fall 2009 pages 395-396 .

- Hoshiro, Hiroyuki "Co-Prosperity Sphere Again? United States Foreign Policy and Japan's "First" Regionalism in the 1950s" pages 385-405 from Pacific Affairs, Volume 82, Issue #3, Fall 2009 page 396.

- Hoshiro, Hiroyuki "Co-Prosperity Sphere Again? United States Foreign Policy and Japan's "First" Regionalism in the 1950s" pages 385-405 from Pacific Affairs, Volume 82, Issue #3, Fall 2009 pages 398-400.

- Hoshiro, Hiroyuki "Co-Prosperity Sphere Again? United States Foreign Policy and Japan's "First" Regionalism in the 1950s" pages 385-405 from Pacific Affairs, Volume 82, Issue #3, Fall 2009 page 405.

- Dower, John War Without Mercy: Race & Power in the Pacific War, New York: Pantheon 1993 pages 244-246

- Hoshiro, Hiroyki "Co-Prosperity Sphere? United States Foreign Policy and Japan's "First" Regionalism in the 1950s" pages 385-405 from Pacific Affairs, Volume 82, Issue #3, Fall 2009 page 399.

- Hoshiro, Hiroyuki "Co-Prosperity Sphere Again? United States Foreign Policy and Japan's "First" Regionalism in the 1950s" pages 385-405 from Pacific Affairs, Volume 82, Issue #3, Fall 2009 page 400.

- Hoshiro, Hiroyki "Co-Prosperity Sphere? United States Foreign Policy and Japan's "First" Regionalism in the 1950s" pages 385-405 from Pacific Affairs, Volume 82, Issue #3, Fall 2009 page 400.

- Hoshiro, Hiroyki "Co-Prosperity Sphere? United States Foreign Policy and Japan's "First" Regionalism in the 1950s" pages 385-405 from Pacific Affairs, Volume 82, Issue #3, Fall 2009 page 400.

- Hoshiro, Hiroyki "Co-Prosperity Sphere? United States Foreign Policy and Japan's "First" Regionalism in the 1950s" pages 385-405 from Pacific Affairs, Volume 82, Issue #3, Fall 2009 page 401.

- Hoshiro, Hiroyki "Co-Prosperity Sphere? United States Foreign Policy and Japan's "First" Regionalism in the 1950s" pages 385-405 from Pacific Affairs, Volume 82, Issue #3, Fall 2009 page 405.

- Hoshiro, Hiroyki "Co-Prosperity Sphere? United States Foreign Policy and Japan's "First" Regionalism in the 1950s" pages 385-405 from Pacific Affairs, Volume 82, Issue #3, Fall 2009 pages 403-404.

- Bix, Herbert Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan, New York: Perennial, 2001 page 661

- Bix, Herbert Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan, New York: Perennial, 2001 page 661.

- Bix, Herbert Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan, New York: Perennial, 2001 page 661.

- Bix, Herbert Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan, New York: Perennial, 2001 pages 661–662.

- Bix, Herbert Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan, New York: Perennial, 2001 page 661.

- Bix, Herbert Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan, New York: Perennial, 2001 page 662

- Bix, Herbert Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan, New York: Perennial, 2001 page 667

- Bonus to be wisely spent, Time, 25 January 1960.

- Foreign Relations of the United States, 1958–1960 Volume XVIII, Japan; Korea, Document 173

- Bix, Herbert Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan, New York: Perennial, 2001 page 663.

- Eckert, Carter Park Chung Hee and Modern Korea: The Roots of Militarism, 1866–1945, Cambridge: Belknap Press, 2016 page 310.

- "The Unquiet Past Seven decades on from the defeat of Japan, memories of war still divide East Asia". The Economist. 12 August 2015. Retrieved 2015-09-09.

- Embassy of India in Japan; Prime Minister's speech to the Japanese diet on 14 December 2006 (Doc file)

- "America's Favorite War Criminal: Kishi Nobusuke and the Transformation of U.S.-Japan Relations" Michael Schaller

- Kim, Hyun-Ki (15 August 2013). "Far from Yasukuni, cemetery honors criminals". Korea JoongAng Daily.

- 三島, 由紀夫 (1975). 一つの政治的意見. 三島由紀夫全集. 29. 新潮社., from

- 三島, 由紀夫 (1960-06-25). "一つの政治的意見". 毎日新聞.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Tanzan Ishibashi |

Prime Minister of Japan Jan 1957 – Jul 1960 |

Succeeded by Hayato Ikeda |

| Preceded by Mamoru Shigemitsu |

Minister of Foreign Affairs Dec 1956 – Jul 1957 |

Succeeded by Aiichiro Fujiyama |

| Preceded by Seizō Sakonji |

Minister of Commerce & Industry Oct 1941 – Oct 1943 |

Succeeded by Hideki Tōjō |