John Nash (architect)

John Nash (18 January 1752 – 13 May 1835) was one of the foremost British architects of the Regency and Georgian eras, during which he was responsible for the design, in the neoclassical and picturesque styles, of many important areas of London. His designs were financed by the Prince Regent, and by the era's most successful property developer, James Burton, with whose son Decimus Burton he collaborated extensively.

John Nash | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 18 January 1752 Lambeth, London, England |

| Died | 13 May 1835 (aged 83) East Cowes Castle, Isle of Wight, England |

| Nationality | British |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Partner(s) | James Burton; Decimus Burton |

| Buildings |

|

Nash's best-known solo designs are the Royal Pavilion, Brighton, Marble Arch, and Buckingham Palace; his best known collaboration with James Burton is Regent Street; and his best-known collaborations with Decimus Burton are Regent's Park and its terraces and Carlton House Terrace. The majority of his buildings, including those to the design of which the Burtons did not contribute, were built by the company of James Burton.

Biography

Background and early career

Nash was born during 1752 in Lambeth, south London, the son of a Welsh millwright also called John (1714–1772).[1] From 1766 or 67, John Nash trained with the architect Sir Robert Taylor; the apprenticeship was completed in 1775 or 1776.[2]

On 28 April 1775, at the now demolished church of St Mary Newington, Nash married his first wife Jane Elizabeth Kerr,[2] daughter of a surgeon. Initially he seems to have pursued a career as a surveyor, builder and carpenter.[3] This gave him an income of around £300 a year.[3] The couple set up home at Royal Row Lambeth.[2] He established his own architectural practice in 1777 as well as being in partnership with a timber merchant, Richard Heaviside.[2][4] The couple had two children, both were baptised at St Mary-at-Lambeth, John on 9 June 1776 and Hugh on 28 April 1778.[2]

In June 1778 "By the ill conduct of his wife found it necessary to send her into Wales in order to work a reformation on her",[5] the cause of this appears to have been the claim that Jane Nash "Had imposed two spurious children on him as his and her own, notwithstanding she had then never had any child"[5] and she had contracted several debts unknown to her husband, including one for milliners' bills of £300.[5] The claim that Jane had faked her pregnancies and then passed babies she had acquired off as her own was brought before the Consistory court of the Bishop of London.[6]

His wife was sent to Aberavon to lodge with Nash's cousin Ann Morgan, but she developed a relationship with a local man Charles Charles. In an attempt at reconciliation Jane returned to London in June 1779, but she continued to act extravagantly so he sent her to another cousin, Thomas Edwards of Neath. She gave birth just after Christmas, and acknowledged Charles Charles as the father.[7] In 1781 Nash instigated action against Jane for separation on grounds of adultery. The case was tried at Hereford in 1782, Charles who was found guilty was unable to pay the damages of £76 and subsequently died in prison.[7] The divorce was finally read 26 January 1787.[6]

His career was initially unsuccessful and short-lived. After inheriting £1000[8] in 1778 from his uncle Thomas, he invested the money in building his first known independent works, 15–17 Bloomsbury Square and 66–71 Great Russell Street in Bloomsbury. But the property failed to let and he was declared bankrupt on 30 September 1783.[9] His debts were £5000,[6] including £2000 he had been lent by Robert Adam and his brothers.[9]

A blue plaque commemorating Nash was placed on 66 Great Russell Street by English Heritage in 2013.[10]

Welsh interlude

Nash left London in 1784 to live in Carmarthen,[11] to where his mother had retired, her family being from the area. In 1785 he and a local man Samuel Simon Saxon re-roofed the town's church for 600 Guineas.[11] Nash and Saxon seem to have worked as building contractors and suppliers of building materials.[12] Nash's London buildings had been standard Georgian terrace houses, and it was in Wales that he matured as an architect. His first major work in the area was the first of three prisons he would design, Carmarthen 1789–92,[13] this prison was planned by the penal reformer John Howard[14] and Nash developed this into the finished building.

He went on to design the prisons at Cardigan (1791–96)[15] and Hereford (1792–96).[14] It was at Hereford that Nash met Richard Payne Knight,[16] whose theories on the picturesque as applies to architecture and landscape would influence Nash. The commission for Hereford Gaol came after the death of William Blackburn, who was to have designed the building, Nash's design was accepted after James Wyatt approved of the design.[17]

By 1789 St David's Cathedral was suffering from structural problems, the west front was leaning forward by one foot,[18] Nash was called in to survey the structure and develop a plan to save the building, his solution completed in 1791 was to demolish the upper part of the facade and rebuild it with two large but inelegant flying buttresses.[19]

In 1790 Nash met Uvedale Price,[20] whose theories of the Picturesque would have a major future influence on Nash's town planning. In the short term Price would commission Nash to design Castle House Aberystwyth (1795). Its plan took the form of a rightangled triangle, with an octagonal tower at each corner,[21] sited on the very edge of the sea. This marked a new and more imaginative approach to design in Nash's work.

One of Nash's most important developments were a series of medium-sized country houses that he designed in Wales, these developed the villa designs of his teacher Sir Robert Taylor.[11] Most of these villas consist of a roughly square plan with a small entrance hall with a staircase offset in the middle to one side, around which are placed the main rooms, there is then a less prominent Servants' quarters in a wing attached to one side of the villa.

The buildings are usually only two floors in height, the elevations of the main block are usually symmetrical. One of the finest of these villas is Llanerchaeron, at least a dozen villas were designed throughout south Wales. Others, in Pembrokeshire, include Ffynone, built for the Colby family at Boncath near Manordeifi, and Foley House, built for the lawyer Richard Foley (brother of Admiral Sir Thomas Foley) at Goat Street in Haverfordwest.

He met Humphry Repton at Stoke Edith in 1792[22] and formed a successful partnership with the landscape garden designer. One of their early commissions was at Corsham Court in 1795–96. The pair would collaborate to carefully place the Nash-designed building in grounds designed by Repton. The partnership ended in 1800 under recriminations,[23] Repton accusing Nash of exploiting their partnership to his own advantage.

As Nash developed his architectural practice it became necessary to employ draughtsmen, the first in the early 1790s was Augustus Charles Pugin,[12] then a bit later in 1795 John Adey Repton son of Humphry.[12]

In 1796, Nash spent most of his time working in London, this was a prelude to his return to the capital in 1797.[24]

Return to London

In June 1797, he moved into 28 Dover Street, a building of his own design. He built a larger house next door at 29, into which he moved the following year.[25] Nash married 25-year-old Mary Ann Bradley on 17 December 1798 at St George's, Hanover Square.[25] In 1798, he purchased a plot of land of 30 acres (12 ha) at East Cowes[26] on which he erected 1798–1802 East Cowes Castle as his residence. It was the first of a series of picturesque Gothic castles that he would design.

Nash's final home in London was No.14 Regent Street that he designed and built 1819–23, No. 16 was built at the same time the home of Nash's cousin John Edwards,[27] a lawyer who handled all of Nash's legal affairs.[28] Located in lower Regent Street, near Waterloo Place, both houses formed a single design around an open courtyard. Nash's drawing office was on the ground floor, on the first floor was the finest room in the house, the 70-foot-long picture and sculpture gallery; it linked the drawing room at the front of the building with the dining room at the rear.[29] The house was sold in 1834 and the gallery interior moved to East Cowes Castle.

The finest of the dozen country houses that Nash designed as picturesque castles include the relatively small Luscombe Castle Devon (1800–04),[30] Ravensworth Castle (Tyne and Wear) begun 1807 only finally completed in 1846, was one of the largest houses by Nash,[31] Caerhays Castle in Cornwall (1808–10),[32] Shanbally Castle, County Tipperary (1818–1819) was the last of these castles to be built.[33] These buildings all represented Nash's continuing development of an asymmetrical and picturesque architectural style, that had begun during his years in Wales, at both Castle House Aberystwyth and his alterations to Hafod Uchtryd.[34]

This process would be extended by Nash in planning groups of buildings, the first example being Blaise Hamlet (1810–1811). There a group of nine asymmetrical cottages was laid out around a village green. Nikolaus Pevsner described the hamlet as "the ne plus ultra of the Picturesque movement".[34] The hamlet has also been described as the first fully realized exemplar of the garden suburb.[35] Nash developed the asymmetry of his castles in his Italianate villas. His first such exercise was Cronkhill (1802),[36] others included Sandridge Park (1805)[37] and Southborough Place, Surbiton, (1808).[38]

He advised on work to the buildings of Jesus College, Oxford in 1815,[39] for which he required no fee but asked that the college should commission a portrait of him from Sir Thomas Lawrence to hang in the college hall.[40]

Architect to the Prince Regent

Nash was a dedicated Whig[41] and was a friend of Charles James Fox through whom Nash probably came to the attention of the Prince Regent (later King George IV). In 1806 Nash was appointed architect to the Surveyor General of Woods, Forests, Parks, and Chases.[42] From 1810 Nash would take very few private commissions and for the rest of his career he would largely work for the Prince.[43] His employment by the Prince Regent enabled Nash to embark upon a number of grand architectural projects.[44]

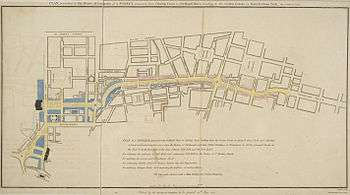

His first major commissions in (1809–1826)[45] from the Prince were Regent Street and the development of an area then known as Marylebone Park. With the Regent's backing, Nash created a master plan for the area, put into effect from 1818 onwards, which stretched from St James's northwards and included Regent Street, Regent's Park (1809–1832)[46] and its neighbouring streets, terraces and crescents of elegant town houses and villas. Nash did not design all the buildings himself. In some instances, these were left in the hands of other architects such as James Pennethorne and the young Decimus Burton.

Nash went on to re-landscape St. James's Park (1814–1827),[47] reshaping the formal canal into the present lake, and giving the park its present form. A characteristic of Nash's plan for Regent Street was that it followed an irregular path linking Portland Place to the north with Carlton House, London (replaced by Nash's Carlton House Terrace (1827–1833)[48]) to the south. At the northern end of Portland Place Nash designed Park Crescent, London (1812) & (1819–1821),[49] this opens into Nash's Park Square, London (1823–24),[50] this only has terraces on the east and west, the north opens into Regent's Park.

The terraces that Nash designed around Regent's park though conforming to the earlier form of appearing as a single building, as developed by John Wood, the Elder, are unlike earlier examples set in gardens and are not orthogonal in their placing to each other. This was part of Nash's development of planning, this found it is most extreme example when he set out Park Village East and Park Village West (1823–34) to the north-east of Regent's Park,[51] here a mixture of detached villas, semi-detached houses, both symmetrical and assymmetrical in their design are set out in private gardens railed off from the street, the roads loop and the buildings are both classical and gothic in style. No two buildings were the same, and or even in line with their neighbours. The park Villages can be seen as the prototype for the Victorian suburbs.[52]

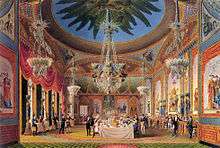

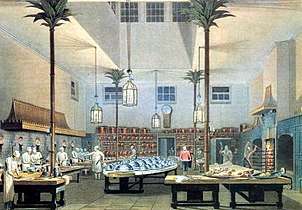

Nash was employed by the Prince from 1815 to develop his Marine Pavilion in Brighton,[53] originally designed by Henry Holland. By 1822 Nash had finished his work on the Marine Pavilion, which was now transformed into the Royal Pavilion. The exterior was based on Mughal architecture, giving the building its exotic form, the Chinoiserie style interiors are largely the work of Frederick Crace.[54]

Nash was also a director of the Regent's Canal[55] Company set up in 1812 to provide a canal link from west London to the River Thames in the east. Nash's masterplan provided for the canal to run around the northern edge of Regent's Park; as with other projects, he left its execution to one of his assistants, in this case James Morgan. The first phase of the Regent's Canal was completed in 1816 and finally completed in 1820.[56]

Together with Robert Smirke and Sir John Soane, he became an official architect to the Office of Works in 1813,[57] (the appointment ended in 1832) at a salary of £500 per annum,[58] following the death in September of that year of James Wyatt, this marked the high point in his professional life. As part of Nash's new position he was invited to advise the Parliamentary Commissioners on the building of new churches from 1818 onwards.[59] Nash produced ten church designs, each estimated to cost around £10,000 with seating for 2000 people,[60] the style of the buildings were both classical and gothic. In the end Nash only built two churches for the Commission, the classical All Souls Church, Langham Place (1822–24) terminating the northern end of Regent Street, and the gothic St. Mary's Haggerston (1825–27),[61] bombed during The Blitz in 1941.

Nash was involved in the design of two of London's theatres, both in Haymarket. The King's Opera House (now rebuilt as Her Majesty's Theatre) (1816–1818) where he and George Repton remodelled the theatre, with arcades and shops around three sides of the building, the fourth being the still surviving Royal Opera Arcade.[62]

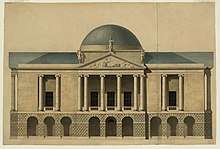

The other theatre was the Theatre Royal Haymarket (1821), with its fine hexastyle Corinthian order portico, which still survives, facing down Charles II Street to St. James's Square, Nash's interior nolonger survives (the interior now dates from 1904).[63]

In 1820 a scandal broke, when a cartoon was published[64] showing a half dressed King George IV embracing Nash's wife with a speech bubble coming from the King's mouth containing the words "I have great pleasure in visiting this part of my dominions". Whether this was based on just a rumour put about by people who resented Nash's success or if there is substance behind is not known.

Further London commissions for Nash followed, including the remodelling of Buckingham House to create Buckingham Palace (1825–1830),[65] and for the Royal Mews (1822–24)[66] and Marble Arch (1828)[67] The arch was originally designed as a triumphal arch to stand at the entrance to Buckingham Palace. It was moved when the east wing of the palace designed by Edward Blore was built, at the request of Queen Victoria whose growing family required additional domestic space. Marble Arch became the entrance to Hyde Park and The Great Exhibition.

Relationship with James Burton (b.1761) and Decimus Burton

The parents of John Nash, and Nash himself during his childhood, lived in Southwark,[68] where James Burton worked as an 'Architect and Builder' and developed a positive reputation for prescient speculative building between 1785 and 1792.[69] Burton built the Blackfriars Rotunda in Great Surrey Street (now Blackfriars Road) to house the Leverian Museum,[70] for land agent and museum proprietor James Parkinson.[71] However, whereas Burton was vigorously industrious, and quickly became 'most gratifyingly rich',[72] Nash's early years in private practice, and his first speculative developments, which failed either to sell or let, were unsuccessful, and his consequent financial shortage was exacerbated by the 'crazily extravagant' wife whom he had married before he had completed his training, until he was declared bankrupt in 1783.[73]

To repair his finances, Nash cultivated the acquaintance of James Burton, who consented to patronize him.[74] James Burton responsible for the social and financial patronage of the majority of Nash's London designs,[75] in addition to for their construction.[76] Architectural scholar Guy Williams has written, 'John Nash relied on James Burton for moral and financial support in his great enterprises. Decimus had showed precocious talent as a draughtsman and as an exponent of the classical style... John Nash needed the son's aid, as well as the father's'.[75]

Subsequent to the Crown Estate's refusal to finance them, James Burton agreed to personally finance the construction projects of Nash at Regent’s Park, which he had already been commissioned to construct.[70][76] Consequently, in 1816, Burton purchased many of the leases of the proposed terraces around, and proposed villas within, Regent's Park,[70] and, in 1817, Burton purchased the leases of five of the largest blocks on Regent Street.[70] The first property to be constructed in or around Regent's Park by Burton was his own mansion: The Holme, which was designed by his son, Decimus Burton, and completed in 1818.[70] Burton's extensive financial involvement 'effectively guaranteed the success of the project'.[70] In return, Nash agreed to promote the career of Decimus Burton.[70]

Nash was a vehement advocate of the neoclassical revival endorsed by Soane, although he had lost interest in the plain stone edifices typical of the Georgian style, and instead advocated the use of stucco.[77] Decimus Burton entered the office of Nash in 1815,[78] where he worked alongside Augustus Charles Pugin, who detested the neoclassical style.[79] Decimus established his own architectural practice in 1821.[80] In 1821, Nash invited Decimus to design Cornwall Terrace in Regent's Park, and Decimus was also invited by George Bellas Greenough, a close friend of the Prince Regent, Humphrey Davy, and Nash, to design Grove House in Regent's Park.[81]

Greenough's invitation to Decimus Burton was 'virtually a family affair', for Greenhough had dined frequently with Decimus's parents and Decimus's brothers, including the physician Henry Burton.[82] Greenough and Decimus finalized their designs during numerous meetings at the opera.[82] Decimus's design, when the villa had been completed, was described in The Proceedings of the Royal Society as, 'One of the most elegant and successful adaptations of the Grecian style to purposes of modern domestic architecture to be found in this or any country'.[83]

Subsequently, Nash invited Burton to design Clarence Terrace, Regent's Park.[83] Such were James Burton’s contributions to the Regent's Park project that the Commissioners of Woods described James, not Nash, as ‘the architect of Regent’s Park’.[84] Contrary to popular belief, the dominant architectural influence in many of the Regent's Park projects - including Cornwall Terrace, York Terrace, Chester Terrace, Clarence Terrace, and the villas of the Inner Circle, including The Holme and the London Colosseum attraction (the latter to Thomas Hornor's specifications)[85][76] all of which were constructed by James Burton's company[70] - was Decimus Burton, not John Nash, who was appointed architectural 'overseer' for Decimus's projects.[84]

To the chagrin of Nash, Decimus largely disregarded his advice and developed the Terraces according to his own style, to the extent that Nash sought unsuccessfully, to demolish and completely rebuild Chester Terrace.[86][76][70] Decimus subsequently eclipsed his master and emerged as the dominant force in the design of Carlton House Terrace,[76] where he exclusively designed No. 3 and No.4.[87] Decimus also designed some of the villas of the Inner Circle: his villa for the Marquess of Hertford has been described as, 'decorated simplicity, such as the hand of taste, aided by the purse of wealth can alone execute'.[88]

Retirement and death

Nash's career effectively ended with the death of George IV in 1830. The King's notorious extravagance had generated much resentment and Nash was now without a protector.[89] The Treasury started to look closely at the cost of Buckingham Palace. Nash's original estimate of the building's cost had been £252,690, but this had risen to £496,169 in 1829[90] the actual cost was £613,269 and the building was still unfinished. This controversy ensured that Nash would not receive any more official commissions nor would he be awarded the Knighthood that other contemporary architects such as Jeffry Wyattville, John Soane and Robert Smirke received. Nash retired to the Isle of Wight to his home, East Cowes Castle.[91]

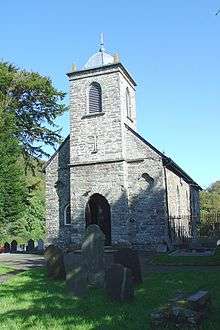

On 28 March 1835 Nash was described as "very poorly and faint".[92] This was the beginning of the end. On 1 May Nash's solicitor John Wittet Lyon was summonsed to East Cowes Castle[92] to finalise his will. By 6 May he was described as 'very ill indeed all day',[93] he died at his home on 13 May 1835. His funeral took place at St. James's Church, East Cowes on 20 May, where he was buried in the churchyard,[93] where the monument takes the form of a stone sarcophagus.

His widow acted to clear Nash's debts (some £15,000),[93] she held a sale of the Castle's contents, including three paintings by J. M. W. Turner painted on the Isle of Wight, two by Benjamin West and several copies of old master paintings by Richard Evans. These artworks were sold at Christie's on 11 July 1835 for £1,061.[93] His books, medals, drawings and engravings were bought by a bookseller named Evans for £1,423 on 15 July. The Castle itself was sold for a reported figure of £20,000 to Henry Boyle, 3rd Earl of Shannon within the year.[93]

Nash's widow retired to a property Nash had bequeathed to her in Hampstead where she lived until her death in 1851; she was buried with her husband on the Isle of Wight.[94]

Assistants and pupils

Nash had many pupils and assistants including Decimus Burton, Humphry Repton's sons, John Adey Repton and George Stanley Repton, as well as Anthony Salvin, John Foulon (1772–1842), Augustus Charles Pugin, F.H. Greenway, James Morgan, James Pennethorne, the brothers Henry, James and George Pain.[95]

Works

Works in London

Works in London include:[96]

- Park Crescent, London (1806, 1819–21)

- Carlton House, alterations, demolished

- Southborough House, 14 Ashcombe Avenue, Southborough, Surbiton (1808)

- Southborough Lodge, 16 Ashcombe Avenue, Southborough, Surbiton (1808)

- 18 Ashcombe Avenue, Southborough, Surbiton (1808) Southborough House's summer house

- Regent Street (1809–1826) rebuilt

- Regent's Canal (1811–1820)

- Royal Lodge (1811–20) subsequently remodelled by Sir Jeffry Wyattville

- Carlton House, London remodelled several interiors, (1812–14) demolished 1825 to make way for Nash's Carlton House Terraces

- Trafalgar Square (1813–30) completely redesigned by Sir Charles Barry

- The Rotunda, Woolwich (1814; re-erected 1820)

- The King's Opera House, Haymarket, on the site of Her Majesty's Theatre. The Royal Opera Arcade is the only part presently standing (1816–18).

- Waterloo Place (1816) rebuilt

- The County Fire Office (1819) rebuilt

- Piccadilly Circus (1820) rebuilt

- Suffolk Place, Haymarket (1820)

- Haymarket Theatre (1820–21)

- 14–16 Regent Street (Nash's own house) (1820–21)

- York Gate (1821)

- The Church of All Souls, Langham Place (1822–25)

- Hanover Terrace (1822)

- Royal Mews (1822–24)

- Sussex Place (1822–23)

- Albany Terrace, London (1823)

- Park Square, London (1823–24)

- Park Village East and West (1823–34)

- Cambridge Terrace (1824)

- Landscaping of King's Road (1824)

- Ulster Terrace (1824)

- Buckingham Palace. The state rooms and western front (1825–30), since much extended by James Pennethorne, Edward Blore, and Aston Webb

- Clarence House (1825–27)

- Cumberland Terrace (1826)

- Former United Services Club Pall Mall now Institute of Directors (1826–28)

- Gloucester Terrace (1827)

- Marble Arch (1828)

- 430–449 Strand (1830)

With Decimus Burton

- Regent's Park (1809 – 1832)[87]

- York Terrace (1822)[76]

- Chester Terrace (1825)[86][76]

- Cornwall Terrace[87]

- Clarence Terrace[87]

- Carlton House Terrace (1827 –1833)[87]

- St. James's Park (1814 – 1827)[87]

The changes made by John Nash to the streetscape of London are documented in the film John Nash and London, featuring Edmund N. Bacon and based on sections of his 1967 book Design of Cities.

All Souls Langham Place

All Souls Langham Place The interior looking east, All Souls Langham Place

The interior looking east, All Souls Langham Place The interior looking west, All Souls Langham Place

The interior looking west, All Souls Langham Place The interior looking north, All Souls Langham Place

The interior looking north, All Souls Langham Place St Mary Haggerston

St Mary Haggerston The Rotunda Woolwich

The Rotunda Woolwich- Cumberland Terrace

Cumberland Terrace

Cumberland Terrace Carlton House Terrace

Carlton House Terrace- Theatre Royal Haymarket

- Buckingham Palace Garden Front

The Royal Mews, Buckingham Palace

The Royal Mews, Buckingham Palace.jpg) Park Crescent

Park Crescent East side, Park Square

East side, Park Square West side, Park Square

West side, Park Square Marble Arch

Marble Arch Chester Terrace

Chester Terrace Detail, Chester Terrace

Detail, Chester Terrace Clarence House

Clarence House York Gate

York Gate- Ulster Terrace

- Former United Services Club

Nash's plan for Regent Street

Nash's plan for Regent Street Conservatory, Kew Gardens

Conservatory, Kew Gardens- King's Opera House, demolished

- Royal Opera Arcade

Hanover Terrace

Hanover Terrace Gloucester Gate

Gloucester Gate Sussex Place

Sussex Place Sussex Place

Sussex Place Regent's Park, still largely as planned by Nash

Regent's Park, still largely as planned by Nash St. James's Park, Nash's lake

St. James's Park, Nash's lake The Gothic Dining Room, Carlton House, Destroyed

The Gothic Dining Room, Carlton House, Destroyed York Terrace

York Terrace Albany Terrace

Albany Terrace Cornwall Terrace

Cornwall Terrace

Work in England outside London

- Blaise Castle, additions, including the conservatory and various buildings in the grounds, dairy, gatehouses etc. (1795-c.1806)

- Kentchurch Court, Pontrilas (c.1795)

- Hereford Gaol (1796)

- Corsham Court, remodelling work (1796–1813). Only his east front survives of the main house, but many of his garden buildings, including the bathhouse originally designed by Capability Brown and remodelled by Nash, are extant.[97]

- Grovelands Park, Enfield, Middlesex (1797)

- Atcham, several houses in the village (1797)

- Attingham Park, new picture gallery and staircase, with further interiors, and entrance lodges (c1797-1808)

- East Cowes Castle on the Isle of Wight (1798–1802) – his home until his death in 1835, demolished 1960.

- Sundridge Park, Sundridge, London, (1799)

- Chalfont Park, Chalfont St Peter, remodelled (1799–1800)

- Helmingham Hall, modernisation work (1800–1803)

- Luscombe Castle (1800–1804)

- Cronkhill, near Shrewsbury, Shropshire. First Italianate villa in Britain. (1802)

- Longner Hall, Atcham, remodelling and extension (1803)

- Nunwell House, Nunwell Isle of Wight (1805–07)

- Sandridge Park (1805)

- Witley Court (1805–06)

- Market House Chichester (1807)

- Ravensworth Castle (1808)

- Caerhays Castle, Cornwall (1808)[98]

- Ingestre Hall (1808–1813) rebuilt later in the 19th century

- Knepp Castle, Sussex, c.1809

- Blaise Hamlet, Bristol (1810–11)

- Guildhall Newport, Isle of Wight (1814)

- Rebuilding of the Royal Pavilion at Brighton (1815–1822)

Blaise Hamlet

Blaise Hamlet Blaise Hamlet

Blaise Hamlet Circular Cottage, Blaise Hamlet

Circular Cottage, Blaise Hamlet Entrance to Attingham Park

Entrance to Attingham Park Cronkhill

Cronkhill Caerhays Castle

Caerhays Castle The Royal Pavilion Brighton

The Royal Pavilion Brighton The entrance, The Royal Pavilion Brighton

The entrance, The Royal Pavilion Brighton Banqueting Room, The Royal Pavilion Brighton

Banqueting Room, The Royal Pavilion Brighton The kitchen, The Royal Pavilion Brighton

The kitchen, The Royal Pavilion Brighton Grovelands Park

Grovelands Park Witley Court

Witley Court- Newport, Guildhall, I.o.W.

Sundridge Park

Sundridge Park Longner Hall

Longner Hall.jpg) Luscombe Castle

Luscombe Castle Remains of Ravensworth Castle

Remains of Ravensworth Castle.jpg) Chalfont Park

Chalfont Park Knepp Castle

Knepp Castle Sundridge Park

Sundridge Park.jpg) Sandridge Park, Devon

Sandridge Park, Devon

Work in Wales

Work in Wales include:[99]

- The stable block at Plas Llanstephan (1788)

- Golden Grove house, Llanfihangel Aberbythych (1788)

- Priory House, Camarthen (1788–89)

- Carmarthen Gaol, (1789–92)

- St David's Cathedral, new west front (1789–1791) completely remodelled by Sir George Gilbert Scott (1862)

- Glanusk Villa, Cadoxton-juxta-Neath (1790)

- Llanfechan house, Llanwenog, Cardiganshire c. 1790 attributed on stylistic grounds

- Meidrim Poor House (1791)

- Newport Bridge (1791–92) abandoned before completion

- Cardigan Gaol, (1791–97)

- Ffynone Mansion, Boncath (1792–96)

- Sion House, Tenby (1792)

- South Sion Lodge, Tenby (1792)

- Emlyn Cottage, Newcastle Emlyn (1792–94) demolished 1881

- Dolaucothi house, Cynwyl Gaeo (1792–96) demolished (c. 1954)

- Tregaron Bridge (1793)

- Abergavenny Market Place (1794–46)

- Foley House, Haverfordwest, Pembrokeshire (1794)

- Hafod Uchtryd, remodelling including octagonal library (1794) demolished 1958.

- Herman Hill House, Haverfordwest (c. 1794)

- Llanerchaeron, Ciliau Aeron, Ceredigion (c. 1794)

- Llysnewydd, Henllan, Ceredigion (1795)

- Whitson Court, near Newport (1795)

- Glanwysc Villa, Llangattock (Crickhowell) (c. 1795)

- Llysnwydd house, Llangeler (c. 1795) attributed on stylistic grounds demolished 1971.

- Temple Druid House, Maenclochog (1795)

- Castle House, later replaced by Old College, Aberystwyth University, (1795)

- The Priory Cardigan, Ceredigion (1795)

- Clytha Park gates, (1797)

- Llanerchaeron, St Non's Church (1798) attributed on stylistic grounds

- Harpton Court, Old Radnor, remodelled (1805) demolished 1956 apart from the service range

- Hawarden Castle, enlargement (1807)

- Nanteos Mansion, planned replanning and new dairy and lodges (1814) not executed

- Rheola House, Resolven (1814–18)

- Picton Memorial, Carmarthen (1827–28) demolished 1846

St. Non's Church Llanerchaeron

St. Non's Church Llanerchaeron Temple Druid House

Temple Druid House- Hafod Uchtryd

Clytha Castle

Clytha Castle Foley House

Foley House Rear facade of Foley House

Rear facade of Foley House Clytha Park Main gates

Clytha Park Main gates Hermon Hill House

Hermon Hill House Ffynone House, wings added later not by Nash

Ffynone House, wings added later not by Nash Hawarden Castle

Hawarden Castle

Work in Ireland

- House for Countess Shannon, County Cork. 1796. Unbuilt.

- Ballindoon House (c.1800) Kingsborough, Derry, County Sligo for Stafford-King-Harmon family. House and stable block.

- Killymoon Castle, near Cookstown, County Tyrone, (1801–07)* . Castle originally built in 1671. Rebuilt in Norman style by Nash for Col. William Stewart at an alleged cost of £80,000. Now well maintained as home of the Coulter family. The parkland is now used as a golf course.

- Lissan Rectory, County Londonderry. 1807. Italianate Villa.

- Kilwaughter Castle, in Kilwaughter, near Larne, County Antrim.[100] (1807). New castillated mansion built for E.J. Agnew incorporating an earlier house (ruined 1951).

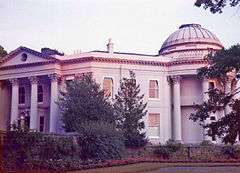

- Caledon House, County Tyrone, (1808–10) for Earl of Caledon. Enlargement and embellishment of an earlier house (1779) by Thomas Cooley with two single storey domed wings connected by a colonnade of coupled Ionic columns; Nash redecorated the oval drawing room.

- Vice-Regal Lodge, Phoenix Park, Dublin (present-day Áras an Uachtaráin, public residence of the President of Ireland), 1808 (entrance lodges only).

- St. John's Church of Ireland church Valentia Island 1815.

- St John's Church Caledon, Count Tyrone (1808). Alterations including timber spire. Spire replaced in stone to same design 1830.

- St. Paul's Church of Ireland church in Cahir, County Tipperary.1816–1818. Cruciform plan.

- Rockingham House, Boyle, County Roscommon (1810). Originally two-storey with curved central bow, fronted by a semi-circular Ionic colonnade, and surmounted by a dome. Built for the King Harmon family. Extra floor added by others. Burnt in fire 1957; subsequently demolished. Parkland now a public park and amenity.

- Rockingham lakeside gazebo.

- Rockingham Gothic Chapel. Roofless.

- Rockingham Castle. Nash may have contributed to picturesque island castle ruin

- Swiss cottage, Cahir County Tipperary.(1810–14) Cottage ornée.

- City Gaol, Limerick City, County Limerick. 1811–1814. New Gaol.

- Lough Cutra Castle, Gort, County Galway(1811–1817) . Built for Charles Vereker subsequently Viscount Gort.

- Shane's Castle in Randalstown, County Antrim (1812–16). Alterations to 17th century castle for 1st Earl O'Neill, consisting of lakeside terrace, and battlemented conservatory with round headed windows, watch-tower and look-out. Burnt down in 1816 before Nash's plans were completed. * Burne Lodge. Crawfordsburn House, Co. Down. 1812. 2-storey gate lodge with octagonal room at first floor level.

- Shanbally Castle, near Clogheen, County Tipperary (1818–19). Built for Cornelius O'Callaghan, 1st Viscount Lismore; largest of Nash's Irish Castles; demolished and dynamited 1960.

- Gracefield Lodge, County Laois, for a Mrs Kavanagh. 1817.

- Erasmus Smith School, Cahir, County Tipperary. 1818.

- Tynan Abbey, Tynan, County Armagh (1820). Remodeled in Tudor Gothic style for Sir James Stronge; gutted by fire 1980. Drawings destroyed after being photographed.

- St. Luran's Church of Ireland, Derryloran Parish, Cookstown. 1822. Cost £2,769.4s.71/2d. Early English style. Rebuilt 1859–61, apart from tower.

- Woodpark Lodge, Co. Armagh. Alterations. 1830s.

- St. Beaidh church, Ardcarne, County Roscommon. Alterations including tower which was an eyecatcher to Rockingham House.

- Somerset House, Coleraine for a Mr Richardson. Date unknown. Unexecuted.

- Mountain Lodge, County Tipperary for Viscount Lismore. Date unknown. Now in a state of disrepair.

- Castle Leslie, County Monaghan. Date unknown. Gateways and gate lodge.

- 80–82 Chapel Street, Cookstown, County Tyrone. Dower house to Killymoon. Date unknown.

- Finaghy House, Belfast. Date unknown.

- Quaker Meering House, Branch Road, Tramore, County Waterford (1869)

Swiss cottage, Cahir

Swiss cottage, Cahir Shanbally Castle

Shanbally Castle.jpg) Lough Cutra Castle

Lough Cutra Castle

Work in Scotland

Nash's only known work in Scotland is:

- St. Mary's Isle, Kirkcudbright, an enclosure around family graves (1796)

Notes

- Tyack 2013, p. 2

- Tyack 2013, p. 3

- Suggett 1995, p. 10

- Major & Murden. A Georgian Heroine: The Intriguing Life of Rachel Charlotte Williams Biggs

- Suggett 1995, p. 11

- Tyack 2013, p. 4

- Suggett 1995, p. 12

- page 16, Terence Davis, John Nash The Prince Regent's Architect, 1966 Country Life

- Tyack 2013, p. 6

- "POWELL, MICHAEL (1905–1990) & PRESSBURGER, EMERIC (1902–1988)". English Heritage. Retrieved 4 May 2014.

- Suggett 1995, p. 13

- Suggett 1995, p. 14

- Summerson 1980, p.14

- Suggett 1995, p. 27

- Suggett 1995, p. 25

- Tyack 2013, p. 19

- Tyack 2013, p. 20

- Suggett 1995, p. 22

- Suggett 1995, p. 23

- Suggett 1995, p. 65

- Suggett 1995, p. 67-69

- Suggett 1995, p. 82

- page 119, Humphry Repton, Dorothy Stroud, 1962, Country Life

- Summerson 1980 p. 27

- Summerson 1980 p. 30

- page 20, East Cowes Castle The Seat of John Nash Esq. A Pictorial History, Ian Sherfield, 1994, Canon Press

- Summerson 1980 p. 132

- Summerson 1980 p. 26

- Mansbridge 1991 p. 227

- Mansbridge 1991 p. 95

- Mansbridge 1991 p. 142

- Mansbridge 1991 p. 149

- Mansbridge 1991 p. 218

- Mansbridge 1991 p. 133

- Stern, Robert A.M.; Fishman, David; Tilove, Jacob (2013). Paradise Planned: The Garden Suburb and the Modern City. The Monacelli Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-1580933261.

- Mansbridge 1991 p. 101

- Mansbridge 1991 p. 118

- Mansbridge 1991 p. 150

- Mansbridge 1991 p. 199

- Baker, J.N.L. (1954). "Jesus College". In Salter, H.E.; Lobel, Mary D. (eds.). A History of the County of Oxford Volume III – The University of Oxford. Victoria County History. Research, University of London. p. 275. ISBN 978-0-7129-1064-4. Retrieved 23 June 2009.

- pages 20–21, Terence Davis, John Nash The Prince Regent's Architect, 1966 Country Life

- Summerson 1980, p. 56

- Summerson 1980, p. 73

- Caves, R. W. (2004). Encyclopedia of the City. Routledge. pp. 480. ISBN 9780415252256.

- Mansbridge 1991, p. 130

- Mansbridge 1991, p. 158-161

- Mansbridge 1991, p. 197

- Mansbridge 1991, p. 296

- Mansbridge 1991, p. 183-184

- Mansbridge 1991, p. 251-252

- Mansbridge 1991, p. 256-262

- Page 382, The Buildings of England, London 4: North, Bridget Cherry & Nikolaus Pevsner, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-14-071049-3

- Mansbridge 1991, p. 201

- Mansbridge 1991, p. 202

- Summerson 1980, p. 72

- Mansbridge 1991, p. 177

- Summerson 1980, p. 96

- Page 98, Sir John Soane Architect, Dorothy Stroud, 1984, Faber & Faber I.S.B.N. 0-571-13050-X

- Port 2006, p. 59

- Port 2006, p. 65

- Port 2006, p. 81

- Mansbridge 1991, p. 206-207

- Mansbridge 1991, p. 230-231

- Summerson 1980, p. 151

- Mansbridge 1991 p. 274

- Mansbridge 1991, p. 244

- Mansbridge 1991, p. 300

- Williams, Guy (1990). Augustus Pugin Versus Decimus Burton: A Victorian Architectural Duel. London: Cassell Publishers Ltd. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-304-31561-1.

- Williams, Guy (1990). Augustus Pugin Versus Decimus Burton: A Victorian Architectural Duel. London: Cassell Publishers Ltd. p. 135. ISBN 978-0-304-31561-1.

- "James Burton [Haliburton]", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography". 2004. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/50182. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Torrens, H. S. "Parkinson, James (bap. 1730, d. 1813), land agent and museum proprietor". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/21370. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Williams, Guy (1990). Augustus Pugin Versus Decimus Burton: A Victorian Architectural Duel. London: Cassell Publishers Ltd. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-304-31561-1.

- Williams, Guy (1990). Augustus Pugin Versus Decimus Burton: A Victorian Architectural Duel. London: Cassell Publishers Ltd. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-304-31561-1.

- Williams, Guy (1990). Augustus Pugin Versus Decimus Burton: A Victorian Architectural Duel. London: Cassell Publishers Ltd. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-304-31561-1.

- Williams, Guy (1990). Augustus Pugin Versus Decimus Burton: A Victorian Architectural Duel. London: Cassell Publishers Ltd. pp. 11–12. ISBN 978-0-304-31561-1.

- Arnold, Dana. "Burton, Decimus". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/4125. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Williams, Guy (1990). Augustus Pugin Versus Decimus Burton: A Victorian Architectural Duel. London: Cassell Publishers Ltd. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-304-31561-1.

- Williams, Guy (1990). Augustus Pugin Versus Decimus Burton: A Victorian Architectural Duel. London: Cassell Publishers Ltd. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-304-31561-1.

- Williams, Guy (1990). Augustus Pugin Versus Decimus Burton: A Victorian Architectural Duel. London: Cassell Publishers Ltd. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-304-31561-1.

- Williams, Guy (1990). Augustus Pugin Versus Decimus Burton: A Victorian Architectural Duel. London: Cassell Publishers Ltd. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-304-31561-1.

- Williams, Guy (1990). Augustus Pugin Versus Decimus Burton: A Victorian Architectural Duel. London: Cassell Publishers Ltd. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-304-31561-1.

- Williams, Guy (1990). Augustus Pugin Versus Decimus Burton: A Victorian Architectural Duel. London: Cassell Publishers Ltd. pp. 38–39. ISBN 978-0-304-31561-1.

- Williams, Guy (1990). Augustus Pugin Versus Decimus Burton: A Victorian Architectural Duel. London: Cassell Publishers Ltd. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-304-31561-1.

- Arnold, Dana (2005). Rural Urbanism: London Landscapes in the Early 19th Century. Manchester University Press. p. 58.

- Basic biographical details of Decimus Burton at the Dictionary of Scottish Architects Biographical Database.

- Curl, James Stevens (1999). The Dictionary of Architecture. Vol. 1 Aba - Byz. Oxford University Press. p. 133. ISBN 978-0-19-860678-9.

- Williams, Guy (1990). Augustus Pugin Versus Decimus Burton: A Victorian Architectural Duel. London: Cassell Publishers Ltd. pp. 135–157. ISBN 978-0-304-31561-1.

- Jones, Christopher (2017). Picturesque Urban Planning - Tunbridge Wells and the Suburban Ideal: The Development of the Calverley Estate 1825 - 1855. University of Oxford, Department of Continuing Education. p. 209.

- Summerson 1980, p. 177

- page 30, Buckingham Palace, John Harris, Geoffrey de Bellaigue & Oliver Miller, 1969, Thomas Nelsons & Sons

- Summerson 1980, p. 185

- Summerson 1980, p. 187

- Summerson 1980, p. 188

- Summerson 1980, p. 189

- A Biographical Dictionary of British Architects 1600–1840, pages 580–581, by Howard Colvin (2nd ed., 1978), John Murray; ISBN 0-7195-3328-7

- The lists of works on this page are based on: John Nash: A complete catalogue, Michael Mansbridge, 1991, Phaidon Press

- Historic England. "The Bath House (Grade I) (1182390)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus Cornwall; Buildings of England series. (1951; 1970) (rev. Enid Radcliffe) Penguin Books (reissued by Yale U. P.) ISBN 0-300-09589-9; p. 192

- Suggett 1995, pp. 107-128

- "John Nash". Dictionary of Ulster Biography. Archived from the original on 5 July 2008. Retrieved 9 July 2008.

References

- Davis, Terence, (1966) John Nash The Prince Regent's Architect, Country Life

- Mansbridge, Michael (1991) John Nash A complete catalogue, Phaidon Press

- Port M.H. (2006) Six Hundred New Churches: The Church Building Commission 1818–1856, 2nd Ed, Yale University Press; ISBN 978-1-904965-08-4

- Suggett, Richard (1995) John Nash Architect in Wales, Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales; ISBN 1-871184-16-9

- Summerson, John (1980) The Life and Work of John Nash Architect, George Allen & Unwin; ISBN 0-04-720021-9

- Tyack, Geoffrey (Ed) (2013) John Nash Architect of the Picturesque, English Heritage; ISBN 978-1-84802-102-0

- Major and Murden "A Georgian Heroine: The Intriguing Life of Rachel Charlotte Williams Biggs"

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to John Nash. |

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.