Yarmouth Castle

Yarmouth Castle is an artillery fort built by Henry VIII in 1547 to protect Yarmouth Harbour on the Isle of Wight from the threat of French attack. Just under 100 feet (30 m) across, the square castle was initially equipped with 15 artillery guns and a garrison of 20 men. It featured an Italianate "arrow-head" bastion on its landward side; this was very different in style from the earlier circular bastions used in the Device Forts built by Henry and was the first of its kind to be constructed in England.

| Yarmouth Castle | |

|---|---|

| Yarmouth, Isle of Wight, England | |

Yarmouth Castle, seen from the north-west | |

Yarmouth Castle | |

| Coordinates | 50°42′24″N 1°30′01″W |

| Type | Henrician castle |

| Site information | |

| Owner | English Heritage |

| Open to the public | Yes |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1547 |

| Events | |

| Official name | Yarmouth Castle |

| Designated | 9 October 1981 |

| Reference no. | 1009391 |

Listed Building – Grade I | |

| Designated | 28 March 1984 |

| Reference no. | 1292631 |

During the 16th and 17th centuries the castle continued to be maintained and modified; the seaward half of the castle was turned into a solid gun platform and additional accommodation was built for the fort's gunners. A bulwark was built on the east side of the castle and an additional gun battery was placed on the town's quay, just to the west. For most of the English Civil War of the 1640s it was held by Parliament; following the Restoration, it was refortified by Charles II in the 1670s.

The fortification remained in use through the 18th and 19th centuries, albeit with a smaller garrison and fewer guns, until in 1885 these were finally withdrawn. After a short period as a coast guard signalling post, the castle was brought back into military use during the First and Second World Wars. In the 21st century, the heritage organisation English Heritage operates the castle as a tourist attraction.

History

16th century

Construction

Yarmouth Castle was built as a consequence of international tensions between England, France and the Holy Roman Empire in the final years of the reign of King Henry VIII. Traditionally the Crown had left coastal defences to the local lords and communities, only taking a small role in building and maintaining fortifications, and while France and the Empire remained in conflict with one another, maritime raids were common but an actual invasion of England seemed unlikely.[1] Modest defences, based around simple blockhouses and towers, existed in the south-west and along the Sussex coast, with a few more impressive works in the north of England, but in general the fortifications were very limited in scale.[2]

In 1533, Henry broke with Pope Paul III to annul the long-standing marriage to his wife, Catherine of Aragon, and remarry.[3] This resulted in France and the Empire declaring an alliance against Henry in 1538, and the Pope encouraged the two countries to attack England.[4] Henry responded in 1539 by ordering the construction of fortifications along the most vulnerable parts of the coast, through an instruction called a "device". The immediate threat passed, but resurfaced in 1544, with France threatening an invasion across the Channel, backed by her allies in Scotland.[5] Henry therefore issued another device in 1544 to further improve the country's defences, particularly along the south coast.[6]

The town of Yarmouth on the Isle of Wight may have been attacked by the French in 1543; if so, this raid probably encouraged the construction of a castle there as part of the second wave of Device Forts.[7][lower-alpha 1] The fort functioned alongside the existing defences in the Solent and protected the main crossing from the west side of the island to the mainland.[9] Yarmouth Castle was a square artillery fort built around a central courtyard with an angular, "arrow-head" bastion protecting the landward side.[10] It was initially equipped with three cannons and culverins, and twelve smaller guns, firing from a line of embrasures along the seaward side of the castle.[10] It was garrisoned by a small team of soldiers, consisting of a master gunner, a porter and 17 soldiers, commanded by Richard Udall, the castle's first captain.[11] Udall lived in the castle, but the soldiers resided in the local town.[12]

The castle was constructed by George Mills under the direction of Richard Worsley, the Captain of the Island, on land belonging to the Crown, possibly on the site of a church destroyed during the events of 1543.[13] Henry had dissolved the monasteries in England a few years before, and stone from the local Quarr Abbey was probably reused in the construction of the castle.[14] It was finished by 1547, when Mills was paid £1,000 for his work and to discharge the soldiers who had been guarding the site during the project.[13][lower-alpha 2]

Initial use

When the Roman Catholic Queen Mary I succeeded to the throne there were changes in the leadership on the Isle of Wight and the castle. Worsley was dismissed in favour of a Roman Catholic appointee in 1553 and Udall was executed in 1555 for his role in the Dudley conspiracy to overthrow the Queen.[16] When the Protestant Elizabeth I came to the throne in 1558, however, peace was made with France and military attention shifted towards the Spanish threat to England.[17] Elizabeth reappointed Worsley to his post and he carried out an extensive redevelopment of the castle.[18] Worsley filled in half of the castle's courtyard to produce a solid artillery platform able to hold eight heavy guns with an uninterrupted field of fire over the sea, and he probably also constructed the Master Gunner's House on the other side of the castle.[19] Nonetheless, an inspection in 1586 showed that the fortification was in poor condition.[14] Work costing £50 was done in 1587, including the erection of an earth bulwark alongside the castle to mount additional guns.[11][lower-alpha 2] The next year saw the attempted invasion of England by the Spanish Armada, after which further repairs were carried out on the castle.[14] By 1599 the Crown was informed that the castle, which was still considered an important defence for the Solent, needed expensive repairs.[20]

17th century

Yarmouth Castle continued to be an important military fortification, used both as a fortress but also as a transport hub and a stores depot.[21] The repairs recommended in 1599 were carried out in the first years of the 17th century and a further £300 was invested in Yarmouth Castle and nearby Sandown Castle in 1609, including adding two angular buttresses along the walls facing the sea.[22][lower-alpha 2]

A survey in 1623 by the castle's captain, John Burley, reported that the garrison comprised only four gunners and the captain, with the buildings in a "ruinous" state and the defences in need of repair; similar concerns were raised in 1625 and 1629.[23] Suggestions that a half-moon battery should be added to the defences were not progressed, but in 1632 the parapets were raised in height and further lodgings and a long room for stores were constructed within the castle.[24] Some of the stone used for this may have been reused from nearby Sandown, whose walls had been destroyed by the sea; before it was used at Sandown, the stone appears to have been taken from the local monasteries.[25]

Civil war broke out in 1642 between the followers of King Charles I and those of Parliament. Initially, Captain Barnaby Burley, a relative of John, and an ardent Royalist, held the castle on behalf of the King with a tiny garrison.[23] Burley negotiated surrender terms, including that he initially be allowed to remain in the castle with armed protection, and the castle remained in the control of Parliament for the rest of the war.[23] Early during the Interregnum it was decided to increase the size of the garrison at the castle from 30 to 70 soldiers, due to concerns about a potential Royalist attack from the island of Jersey.[23] Most of the soldiers lived outside the castle itself.[25] The annual cost of this force was around £78 and in 1655 the garrison was made smaller again to reduce costs.[14][lower-alpha 2]

When Charles II returned to the throne in 1660, he demobilised most of the existing army and the following year the garrison at Yarmouth was given four days notice to leave the castle.[26] The King announced that the castle's artillery would be sent to Cowes, unless the town of Yarmouth agreed to take over the financial responsibility of running the site themselves.[27] The town declined to do so, but Charles repeated the offer in 1666; this time Yarmouth seems to have taken action, appointing four soldiers for a garrison, although the town did not assign an officer to command them, or apparently make any repairs to the now dilapidated castle.[14]

The Crown took over the castle again in 1670, and Robert Holmes, the new Captain of the Isle of Wight, had some of the guns brought back from Cowes to the castle.[27] The site was refortified and a new battery placed on the adjacent quay, but the older earthworks were demolished and the moat was filled in.[27] Holmes built a mansion for himself alongside the castle, where on three occasions he hosted the King.[28]

In 1688, Charles' brother, James II, faced widespread revolt and a potential invasion of England by William of Orange. Holmes was a supporter of James, but although he intended to control Yarmouth Castle on the monarch's behalf, the local inhabitants and the garrison at Yarmouth sided with William, preventing him from openly siding with the King.[27]

18th–21st centuries

Yarmouth Castle continued to be used, and records from 1718 and 1760 show it was equipped with eight 6-pound (2.7 kg) and five 9-pound (4.1 kg) guns along the castle and the quay platforms, respectively.[29] Throughout this period it was probably staffed by a captain and six gunners, supported by the local militia.[30] In the early 18th century, Holmes' mansion was rebuilt, forming its current appearance.[31] By the 18th century, however, Yarmouth Harbour had gradually silted up and been destroyed by industrial developments, reducing the value of the anchorage, and the design of the castle had become outdated.[32]

In 1813, during the Napoleonic Wars, work was carried out to alter the design of the parapet.[33] The Crimean War sparked a fresh invasion scare and in 1855 the south coast of England was refortified.[34] Yarmouth Castle underwent considerable repairs that year; four naval guns and traversing rails were installed on the castle platform, and a regular county army unit was put in place to garrison the fort.[14] In 1881 a proposal was put forward to modernise the entire fortification, but this was rejected and in 1885 the garrison and the guns were withdrawn.[35]

The coastguard began using the castle as a signalling station in 1898.[36] In 1901, the War Department passed the castle to the Commissioners of Woods and Forests and in 1912 parts of the castle were leased to the Pier Hotel, which incorporated Robert Holmes's former mansion; the Pier Hotel eventually became the George Hotel and still occupies part of the old castle moat.[37] The Office of Works took control of the castle in 1913, carrying out a programme of repairs, and it was used by the military in both the First and Second World Wars.[38] It was finally retired from military use in the 1950s.[35]

In the 21st century, Yarmouth Castle is run by the heritage organisation English Heritage as a tourist attraction, receiving 9,007 visitors in 2010.[39] It is protected under UK law as a Grade I listed building and as a scheduled monument.[40]

Architecture

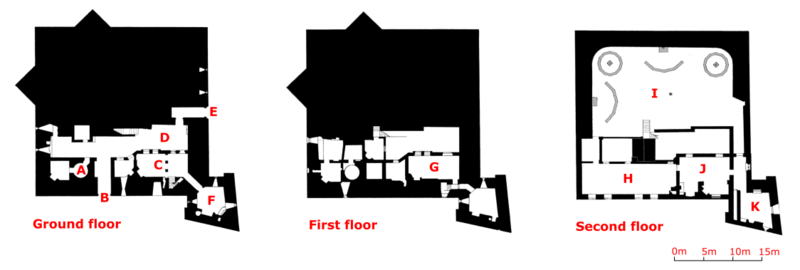

Yarmouth Castle is a square fortification, nearly 100 feet (30 m) across, with an arrow-head bastion protecting the landward side.[41] The north and west walls face the sea, protected by angular buttresses, and a 10-metre (33 ft) wide moat originally protected the south and east side, although this has since been filled in.[42] The castle's 16th-century bulwark, which originally covered the area to the west of Pier Street and the north of Quay Street, and its quay battery have also been destroyed.[43]

The walls of the castle are mainly built from ashlar stone, with some red brick used on the south side.[24] The walls are pierced by a small number of gunloops, including in the "ears" of the bastion, which would have overlooked the moat.[44] When first built the interior of the castle formed a sequence of buildings around a courtyard, but the southern half of the castle was filled in shortly afterwards to produce a solid gun platform able to support heavy guns.[45] It was later raised again in the 17th century to its current height.[45] The parapet is now covered with turf, with 19th-century rounded corners, and the platform still has the rails on which the four naval guns would have traversed, dating from 1855.[46] A small lodging room, built on the platform at the top of the stairs, has since been destroyed.[46]

The arrow-head design of the castle's bastion reflected new ideas about defensive fortifications spreading out from Italy in the 16th century.[47] Earlier Henrician castles had used the older European style of semi-circular bastions to avoid presenting any weak spots in the stonework, but an arrow-headed design enabled defenders to provide much more effective supporting fire against an attacking force.[48] Yarmouth was among the first fortifications in Europe, and the first in England, to adopt this design.[44]

The accommodation and other facilities are on the south side of the castle.[49] On the ground floor, the entrance to the castle leads through to a courtyard, linked to four barrel-vaulted rooms in the south-west corner, originally 17th-century lodgings for the garrison.[50] Two of these chambers were converted for use as magazines and the fittings of one of these still remains in place.[50] In the south-east corner is the Master Gunner's House, comprising a parlour, hall and kitchen on the ground floor, and a chamber and attic on the floors above.[51] The parlour and hall would have originally been separated by a screen; the chamber would also have been subdivided.[52] On the first floor is a small chamber, supported on arches above the courtyard, which was used as a lodging.[53] On the second floor, the Long Room runs on top of the barrel-vaulted chambers, its massive, original roof still intact.[54]

Notes

- Historians are divided as to whether the French attack of 1543 reached the town; Stuart Rigold suggests that they did not move this far across the island, while W. Page and C. Winter argue the reverse.[8]

- Comparing early modern costs and prices with those of the modern period is challenging. £1,000 in 1547 could be equivalent to between £497,000 and £210 million in 2014, depending on the price comparison used, and £50 in 1587 to between £11,000 and £4.4 million. £300 in 1609 could equate to between £50,000 and £14 million; £78 in 1655 to between £12,000 and £2.4 million. For comparison, the total royal expenditure on all the Device Forts across England between 1539–47 came to £376,500, with St Mawes, for example, costing £5,018, and Sandgate £5,584.[15]

References

- Thompson 1987, p. 111; Hale 1983, p. 63

- King 1991, pp. 176–177

- Morley 1976, p. 7

- Morley 1976, p. 7; Hale 1983, pp. 63–64

- Hale 1983, p. 80

- Harrington 2007, pp. 29–30

- Hopkins 2004, p. 3

- Rigold 2012, p. 13; Hopkins 2004, p. 3

- Rigold 2012, pp. 12–13

- Rigold 2012, pp. 11, 13; William Page, ed. (1912), "The Borough of Yarmouth", British History Online, retrieved 14 June 2015

- Rigold 2012, p. 14; William Page, ed. (1912), "The Borough of Yarmouth", British History Online, retrieved 14 June 2015

- Rigold 2012, p. 14

- William Page, ed. (1912), "The Borough of Yarmouth", British History Online, retrieved 14 June 2015; "List Entry", Historic England, retrieved 14 June 2015; Rigold 2012, p. 13

- William Page, ed. (1912), "The Borough of Yarmouth", British History Online, retrieved 14 June 2015

- Biddle et al. 2001, p. 12; Lawrence H. Officer; Samuel H. Williamson (2014), "Five Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a UK Pound Amount, 1270 to Present", MeasuringWorth, retrieved 29 May 2015

- Rigold 2012, p. 13; Fritze 1982, pp. 274–275

- Biddle et al. 2001, p. 40; Pattison 2009, pp. 34–35

- Rigold 2012, p. 13

- Rigold 2012, pp. 11, 13–14; Hopkins 2004, p. 7

- William Page, ed. (1912), "The Borough of Yarmouth", British History Online, retrieved 14 June 2015; Rigold 2012, p. 14

- Rigold 2012, pp. 14–15

- William Page, ed. (1912), "The Borough of Yarmouth", British History Online, retrieved 14 June 2015; "List Entry", Historic England, retrieved 14 June 2015; Rigold 2012, pp. 14–15

- William Page, ed. (1912), "The Borough of Yarmouth", British History Online, retrieved 14 June 2015; Rigold 2012, p. 15

- "List Entry", Historic England, retrieved 14 June 2015

- Rigold 2012, p. 15

- William Page, ed. (1912), "The Borough of Yarmouth", British History Online, retrieved 14 June 2015; "List Entry", Historic England, retrieved 14 June 2015

- William Page, ed. (1912), "The Borough of Yarmouth", British History Online, retrieved 14 June 2015; Rigold 2012, p. 16

- Hopkins 2004, p. 7; William Page, ed. (1912), "The Borough of Yarmouth", British History Online, retrieved 14 June 2015

- Rigold 2012, p. 18

- William Page, ed. (1912), "The Borough of Yarmouth", British History Online, retrieved 14 June 2015; Rigold 2012, p. 18

- Rigold 2012, p. 16

- Hopkins 2004, p. 3; Rigold 2012, p. 1

- Rigold 2012, pp. 18–19

- "History of St Catherine's Castle", English Heritage, retrieved 14 June 2015

- Rigold 2012, p. 19

- William Page, ed. (1912), "The Borough of Yarmouth", British History Online, retrieved 14 June 2015; Rigold 2012, p. 19

- William Page, ed. (1912), "The Borough of Yarmouth", British History Online, retrieved 14 June 2015; Hopkins 2004, p. 7; Rigold 2012, p. 19

- Rigold 1958, p. 6

- "Yarmouth Castle", English Heritage, retrieved 14 June 2015; BDRC Continental (2011), "Visitor Attractions, Trends in England, 2010" (PDF), Visit England, p. 65, archived from the original (PDF) on 19 September 2015, retrieved 19 September 2015

- "Yarmouth Castle, Yarmouth", British Listed Buildings, retrieved 14 June 2015

- Rigold 2012, p. 3

- Rigold 2012, p. 3; Hopkins 2004, p. 7

- Hopkins 2004, p. 7

- Rigold 2012, p. 4

- Rigold 2012, p. 5

- Rigold 2012, p. 11

- Saunders 1989, p. 55

- Saunders 1989, pp. 50–55

- Rigold 2012, pp. 7–8

- Rigold 2012, pp. 6–7

- Rigold 2012, pp. 8–9

- Rigold 2012, p. 9

- Rigold 2012, p. 10

- Rigold 2012, pp. 10–11

Bibliography

- Biddle, Martin; Hiller, Jonathon; Scott, Ian; Streeten, Anthony (2001). Henry VIII's Coastal Artillery Fort at Camber Castle, Rye, East Sussex: An Archaeological Structural and Historical Investigation. Oxford, UK: Oxbow Books. ISBN 0904220230.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fritze, Ronald H. (1982). "The Role of Family and Religion in the Local Politics of Early Elizabethan England: The Case of Hampshire in the 1560s". The Historical Journal. 25 (2): 267–287.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hale, J. R. (1983). Renaissance War Studies. London, UK: Hambledon Press. ISBN 0907628176.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Harrington, Peter (2007). The Castles of Henry VIII. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 9781472803801.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hopkins, Dave (2004). Extensive Urban Survey – Hampshire and the Isle of Wight. London, UK: English Heritage. doi:10.5284/1000227.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- King, D. J. Cathcart (1991). The Castle in England and Wales: An Interpretative History. London, UK: Routledge Press. ISBN 9780415003506.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Morley, B. M. (1976). Henry VIII and the Development of Coastal Defence. London, UK: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. ISBN 0116707771.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pattison, Paul (2009). Pendennis Castle and St Mawes Castle. London, UK: English Heritage. ISBN 9781850747239.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rigold, S. E. (1958). Yarmouth Castle, Isle of Wight. London, UK: HMSO. OCLC 810988359.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rigold, S. E. (2012) [1978]. Yarmouth Castle, Isle of Wight (revised ed.). London, UK: English Heritage. ISBN 9781850740490.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Saunders, Andrew (1989). Fortress Britain: Artillery Fortifications in the British Isles and Ireland. Liphook, UK: Beaufort. ISBN 1855120003.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thompson, M. W. (1987). The Decline of the Castle. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 1854226088.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Yarmouth Castle. |