History of the International Phonetic Alphabet

The International Phonetic Alphabet was created soon after the International Phonetic Association was established in the late 19th century. It was intended as an international system of phonetic transcription for oral languages, originally for pedagogical purposes. The Association was established in Paris in 1886 by French and British language teachers led by Paul Passy. The prototype of the alphabet appeared in Phonetic Teachers' Association (1888b). The Association based their alphabet upon the Romic alphabet of Henry Sweet, which in turn was based on the Phonotypic Alphabet of Isaac Pitman and the Palæotype of Alexander John Ellis.[1]

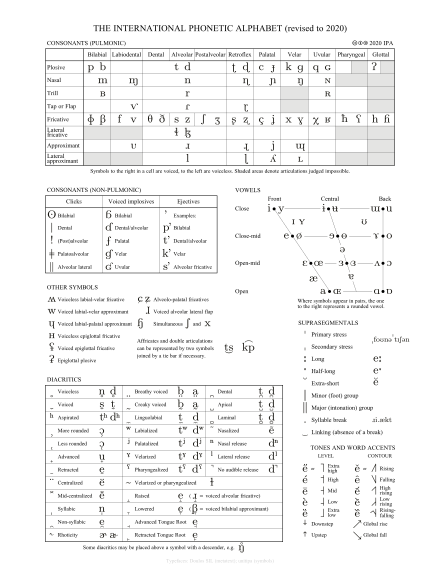

The alphabet has undergone a number of revisions during its history, the most significant being the one put forth at the Kiel Convention in 1989. Changes to the alphabet are proposed and discussed in the Association's organ, Journal of the International Phonetic Association, previously known as Le Maître Phonétique and before that as The Phonetic Teacher, and then put to a vote by the Association's Council.

The extensions to the IPA for disordered speech were created in 1990, with its first major revision approved in 2016.[2]

Early alphabets

The International Phonetic Association was founded in Paris in 1886 under the name Dhi Fonètik Tîtcerz' Asóciécon (The Phonetic Teachers' Association), a development of L'Association phonétique des professeurs d'Anglais ("The English Teachers' Phonetic Association"), to promote an international phonetic alphabet, designed primarily for English, French, and German, for use in schools to facilitate acquiring foreign pronunciation.[3]

Originally the letters had different phonetic values from language to language. For example, English [ʃ] was transcribed with ⟨c⟩ and French [ʃ] with ⟨x⟩.[4]

As of May and November 1887, the alphabets were as follows:[5][6]

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

1888 alphabet

In the August–September 1888 issue of its journal, the Phonetic Teachers' Association published a standardized alphabet intended for transcription of multiple languages, reflecting its members' consensus that only one set of alphabet ought to be used for all languages,[7] along with a set of six principles:

- There should be a separate sign for each distinctive sound; that is, for each sound which, being used instead of another, in the same language, can change the meaning of a word.

- When any sound is found in several languages, the same sign should be used in all. This applies also to very similar shades of sound.

- The alphabet should consist as much as possible of the ordinary letters of the roman alphabet; as few new letters as possible being used.

- In assigning values to the roman letters, international usage should decide.

- The new letters should be suggestive of the sounds they represent, by their resemblance to the old ones.

- Diacritic marks should be avoided, being trying for the eyes and troublesome to write.[8]

The principles would govern all future development of the alphabet, with the exception of #5 and in some cases #2,[9] until they were revised drastically in 1989.[10] #6 has also been loosened, as diacritics have been admitted for limited purposes.[11]

The devised alphabet was as follows. The letters marked with an asterisk were "provisional shapes", which were meant to be replaced "when circumstances will allow".[8]

| Shape | Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| English | French | German | Other languages | ||

| p | as in | put | pas | pferd | |

| b | but | bas | boot | ||

| t | ten | tant | tot | ||

| d | den | dent | da | ||

| k | kind | képi | kuh | ||

| g | good | gai | gut | ||

| m | my | ma | mein | ||

| n | no | non | nein | ||

| ɴ | règne | Ital. regno | |||

| *ɴ | thing | ding | Ital. anche | ||

| l | lull | la | lang | ||

| *ʎ | fille (in the south) | Sp. llano, Ital. gli | |||

| r | red | rare | rot | (tongue-point r) | |

| ʀ | rare | rot | (back r). – Dan. træ | ||

| ᴜ | quer | Flem. wrocht, Span. bibir. | |||

| ɥ | buis | ||||

| w | wel | oui | Ital. questo | ||

| f | full | fou | voll | ||

| v | vain | vin | wein | ||

| θ | thin | Span. razon | |||

| ð | then | Dan. gade | |||

| s | seal | sel | weiss | ||

| z | zeal | zèle | weise | ||

| *c | she | chat | fisch | Swed. skæl, Dan. sjæl, Ital. lascia | |

| ʒ | leisure | jeu | genie | ||

| ç | ich | ||||

| j | you | yak | ja | Swed. ja, Ital. jena | |

| x | ach | Span. jota | |||

| q | wagen | ||||

| h | high | (haut) | hoch | ||

| u | full | cou | nuss | ||

| o | soul | pot | soll | ||

| ɔ | not | note | Ital. notte | ||

| ᴀ | pas | vater | Swed. sal | ||

| *a | father | Ital. mano, Swed. mann. | |||

| a | eye, how | patte | mann | ||

| æ | man | ||||

| ɛ | air | air | bær | ||

| e | men | né | nett | ||

| i | pit | ni | mit | ||

| *œ | but, fur | ||||

| œ | seul | kœnnen | |||

| *ɶ | peu | sœhne | |||

| y | nu | dünn | |||

| *ü | für | ||||

| ə | never | je | gabe | ||

| ʼ | Glottal catch | ||||

| -u, u- | Weak stressed u | These modifications apply to all letters | |||

| ·u, u·, u̇ | Strong stressed u | ||||

| u: | Long u | ||||

| œ̃ | Nasal œ (or any other vowel) | ||||

| û | Long and narrow u (or any other vowel) | ||||

| hl, lh | Voiceless l (or any other consonant) | ||||

| : | Mark of length | ||||

1900 chart

During the 1890s, the alphabet was expanded to cover sounds of Arabic and other non-European languages which did not easily fit the Latin alphabet.[4]

Throughout the first half of the 1900s, the Association published a series of booklets outlining the specifications of the alphabet in several languages, the first being a French edition published in 1900.[12] In the book, the chart appeared as follows:[13]

| Laryn- gales |

Guttu- rales |

Uvu- laires |

Vélaires | Palatales | Linguales | Labiales | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosives | ʔ | q ɢ | k ɡ | c ɟ | t d | p b | ||

| Nasales | ŋ | ɲ | n | m | ||||

| Latérales | ł | ʎ | l | |||||

| Roulées | ꞯ (Q) | ᴙ ʀ | r | |||||

| Fricatives | h | ʜ ɦ | ᴚ ʁ | (ʍ w) x ǥ[lower-alpha 2] | (ɥ) ç j | ɹ, θ ð, ʃ ʒ, s z

ᵷ ʒ [14] |

f v ꜰ ʋ

ʍ w ɥ | |

| Fermées | uɯüïyi

ᴜ ʏı

oⱯöëøe

ə

ɐæ

ɑa |

(u ü y)

(o ö ø)

(ɔ ɔ̈ œ) | ||||||

| Mi-fermées | ||||||||

| Moyennes | ||||||||

| Mi-ouvertes | ||||||||

| Ouvertes | ||||||||

Initially, the charts were arranged with laryngeal sounds on the left and labial ones on the right, following the convention of Alexander Melville Bell's Visible Speech.[16] Vowels and consonants were placed in a single chart, reflecting how sounds ranged in openness from stops (top) to open vowels (bottom). The voiced velar fricative was represented by ⟨![]()

Not all letters, especially those in the fricatives row which included both fricatives in the modern sense and approximants, were self-explanatory and could only be discerned in the notes following the chart, which redefined letters using the orthographies of languages wherein the sounds they represent occur. For example:

(ꞯ) [Q] [is] the Arabic ain [modern ⟨ʕ⟩]. (ꜰ) (ʋ) is a simple bilabial fricative [modern ⟨ɸ β⟩] ... (θ) is the English hard th, Spanish z, Romaic [Greek] θ, Icelandic þ; (ð) the English soft th, Icelandic ð, Romaic δ. (ɹ) is the non-rolled r of Southern British, and can also be used for the simple r of Spanish and Portuguese [modern ⟨ɾ⟩] ... (x) is found in German in ach; (ǥ), in wagen, as often pronounced in the north of Germany [modern ⟨ɣ⟩]. (ᴚ) is the Arabic kh as in khalifa [modern ⟨χ⟩]; (ʁ) the Danish r; the Parisian r is intermediate between (ʀ) and (ʁ). — (ʜ) [modern ⟨ħ⟩] and (ɦ) are the ha and he in Arabic.[20] — (ᵷ) and (ʒ) are sounds in Circassian [approximately modern ⟨ɕ ʑ⟩[21]].[22]

Nasalized vowels were marked with a tilde: ⟨ã⟩, ⟨ẽ⟩, etc. It was noted that ⟨ə⟩ may be used for "any vowel of obscure and intermediate quality found in weak syllables".[22] A long sound was distinguished by trailing ⟨ː⟩. Stress may be marked by ⟨´⟩ before the stressed syllable, as necessary, and the Swedish and Norwegian 'compound tone' (double tone) with ⟨ˇ⟩ before the syllable.[22]

A voiced sound was marked by ⟨◌̬⟩ and a voiceless one by ⟨◌̥⟩. Retroflex consonants were marked by ⟨◌̣⟩, as in ⟨ṣ, ṭ, ṇ⟩. Arabic emphatic consonants were marked by ⟨◌̤⟩: ⟨s̤, t̤, d̤⟩. Consonants accompanied by a glottal stop (ejectives) were marked by ⟨ʼ⟩: ⟨kʼ, pʼ⟩. Tense and lax vowels were distinguished by acute and grave accents: naught [nɔ́ːt], not [nɔ̀t]. Non-syllabic vowels were marked by a breve, as in ⟨ŭ⟩, and syllabic consonants by an acute below, as in ⟨n̗⟩. Following letters, ⟨⊢⟩ stood for advanced tongue, ⟨⊣⟩ for retracted tongue, ⟨˕⟩ for more open, ⟨˔⟩ for more close, ⟨˒⟩ for more rounded, and ⟨˓⟩ for more spread. It was also noted that a superscript letter may be used to indicate a tinge of that sound in the sound represented by the preceding letter, as in ⟨ʃᶜ̧⟩.[23]

It was emphasized, however, that such details need not usually be repeated in transcription.[23] The equivalent part of the 1904 English edition said:

[I]t must remain a general principle to leave out everything self-evident, and everything that can be explained once for all. This allows us to dispense almost completely with the modifiers, and with a good many other signs, except in scientific works and in introductory explanations. We write English fill and French fil the same way fil; yet the English vowel is 'wide' and the French 'narrow', and the English l is formed much further back than the French. If we wanted to mark these differences, we should write English fìl⊣, French fíl⊢. But we need not do so: we know, once for all, that English short i is always ì, and French i always í; that English l is always l⊣ and French l always l⊢.[24]

1904 chart

In the 1904 Aim and Principles of the International Phonetic Association, the first of its kind in English, the chart appeared as:[25]

| Bronchs | Throat | Uvula | Back | Front | Tongue-point | Lip | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stopped | ˀ | q ɢ | k ɡ | c ɟ | t d | p b | ||

| Nasal | ŋ | ɲ | n | m | ||||

| Side | ɫ | ʎ | l | |||||

| Trilled | ᴙ ʀ | r | ||||||

| Squeezed | ʜ ꞯ [Q] | h ɦ | ᴚ ʁ | (ʍ w) x ǥ[lower-alpha 2] | (ɥ) ç j | ɹ, θ ð, ʃ ʒ, s z | f v ꜰ ʋ

ʍ w ɥ | |

| Close | uɯüïyi

ʊ ʏı

oⱯöëøe

ə

ɔʌɔ̈äœɛ

ɐæ

ɑa |

(u ü y)

(ʊ ʏ)

(o ö ø)

(ɔ ɔ̈ œ) | ||||||

| Half-close | ||||||||

| Mid | ||||||||

| Half-open | ||||||||

| Open | ||||||||

In comparison to the 1900 chart, the glottal stop appeared as a modifier letter ⟨ˀ⟩ rather than a full letter ⟨ʔ⟩, ⟨ʊ⟩ replaced ⟨ᴜ⟩, and ⟨ɫ⟩ replaced ⟨ł⟩. ⟨ᵷ, ʒ⟩ were removed from the chart and instead only mentioned as having "been suggested for a Circassian dental hiss [sibilant] and its voiced correspondent".[24] ⟨σ⟩ is suggested for the Bantu labialized sibilant, and ⟨*⟩ as a diacritic to mark click consonants. It is noted that some prefer iconic ⟨ɵ ʚ⟩ to ⟨ø œ⟩, and that ⟨ı⟩ and ⟨ː⟩ are unsatisfactory letters.

Laryngeal consonants had also been moved around, reflecting little understanding about the mechanisms of laryngeal articulations at the time.[26] ⟨ʜ⟩ and ⟨ꞯ⟩ (Q) were defined as the Arabic ح and ع.[27]

In the notes, the half-length mark ⟨ˑ⟩ is now mentioned, and it is noted that whispered sounds may be marked with a diacritical comma, as in ⟨u̦, i̦⟩. A syllabic consonant is now marked by a vertical bar, as in ⟨n̩⟩, rather than ⟨n̗⟩.[28] It is noted, in this edition only, that "shifted vowels" may be indicated: ⟨⊣⊣⟩ for in-mixed or in-front, and ⟨⊢⊢⟩ for out-back.[29]

1912 chart

Following 1904, sets of specifications in French appeared in 1905 and 1908, with little to no changes.[30][31] In 1912, the second English booklet appeared. For the first time, labial sounds were shown on the left and laryngeal ones on the right:[32]

| Lips | Lip-teeth | Point and Blade | Front | Back | Uvula | Throat | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosive | p b | t d | c ɟ | k ɡ | q ɢ | ˀ | ||

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ŋ | ɴ | |||

| Lateral | l ɫ | ʎ | (ɫ) | |||||

| Rolled | r ř | ʀ | ||||||

| Fricative | ꜰ ʋ

ʍ w ɥ

σ ƍ |

f v | θ ð s z

σ ƍ ʃ ʒ ɹ |

ç j (ɥ) | (ʍ w) x ǥ[lower-alpha 2] | ᴚ ʁ | h ɦ | |

Front Mixed Back |

||||||||

| Close | (u ü y)

(ʊ ʏ)

(o ö ø)

(ɔ ɔ̈ œ) |

i yï üɯ u

ɪ ʏʊ

e øë öⱯ o

ə

ɛ œɛ̈ ɔ̈ʌ ɔ

æɐ

aɑ | ||||||

| Half-close | ||||||||

| Half-open | ||||||||

| Open | ||||||||

⟨ř⟩ was added for the Czech fricative trill, ⟨ɛ̈⟩ replaced ⟨ä⟩ and ⟨ɪ⟩ replaced ⟨ı⟩, following their approval in 1909.[33] Though not included in the chart, ⟨ɱ⟩ was mentioned as an optional letter for the labiodental nasal. ⟨ɹ⟩ was still designated as the "provisional" letter for the alveolar tap/flap. ⟨σ, ƍ⟩ were defined as the Bantu sounds with "tongue position of θ, ð, combined with strong lip-rounding". ⟨ʜ, ꞯ⟩ (Q) were still included though not in the chart.[34] ⟨ᴙ⟩ was removed entirely.

For the first time, affricates, or "'[a]ssibilated' consonant groups, i. e. groups in which the two elements are so closely connected that the whole might be treated as a single sound", were noted as able to be represented with a tie bar, as in ⟨t͡ʃ, d͜z⟩. Palatalized consonants could be marked by a dot above the letter, as in ⟨ṡ, ṅ, ṙ⟩, "suggesting the connexion with the sounds i and j".[35]

⟨⊢, ⊣⟩ were no longer mentioned.

1921 chart

The 1921 Écriture phonétique internationale introduced new letters, some of which were never to be seen in any other booklet:[36]

| Laryn- gales |

Uvu- laires |

Vélaires | Palatales | Linguales | Labiales | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosives | ʔ[37] | q ɢ | k ɡ | c ɟ | t d | p b | |

| Nasales | ɴ | ŋ | ɲ | n | m | ||

| Latérales | ʎ | l | |||||

| Roulées | ᴙ ʀ | r | |||||

| Fricatives | h | χ ʁ | (ƕ w) x ǥ[lower-alpha 2] | ( |

ʃ ʒ s z

ɹ θ ð |

f v ꜰ ʋ

ƕ w | |

| Fermées | u ɯʉ ɨy i

ə

ɔ ʌʚ ɜœ ɛ

ɐ

ɑa |

(u ʉ y)

(o ɵ ø)

(ɔ ʚ œ) | |||||

| Mi-fermées | |||||||

| Mi-ouvertes | |||||||

| Ouvertes | |||||||

⟨χ⟩ replaced ⟨ᴚ⟩ and ⟨ɤ⟩ replaced ⟨Ɐ⟩, both of which would not officially be approved until 1928.[39] ⟨ƕ⟩ replaced ⟨ʍ⟩ and ⟨![]()

The book also mentioned letters "already commonly used in special works", some of which had long been part of the IPA but others which "have not yet been definitively adopted":[42]

- ⟨ɾ⟩ for a single-tap r

- ⟨ř⟩ for the Czech fricative trill

- ⟨ɦ⟩ for a voiced [h]

- ⟨ħ, ʕ⟩ for the Arabic ح and ع, "whose formation we do not yet agree on"

- ⟨σ, ƍ⟩ (dental) and ⟨ƪ, ƺ⟩ (alveolar or palatal) for labiolized sibilants found in South African languages

- As "suggested":

- ⟨ᵷ, ʒ⟩ for Circassian dental fricatives

- ⟨ɮ⟩ for fricative [l] of Bantu languages

- ⟨ɺ⟩ for a sound between [r] and [l] found in African languages and in Japanese

- Small j for palatalized consonants: ⟨ƫ, ᶎ⟩

- Overlaying tilde for velarized and Arabic emphatic consonants: ⟨ᵵ, ᵭ⟩

- ⟨ɕ, ʑ⟩ for "dentalized palatals"

- ⟨

- ⟨ʧ⟩, ⟨ʤ⟩, ⟨ʦ⟩, ⟨ʣ⟩, ⟨pf⟩, ⟨tl⟩, etc. for affricates

- ⟨ᴜ, ɪ, ʏ⟩ for the near-close equivalents of [o, e, ø]

- ⟨ɒ, æ⟩ for the near-open vowels in English not, man

- ⟨ʇ, ʖ, ʞ, ʗ⟩ for clicks, with ⟨ʞ⟩ for the common palatal click (this would be called "velar" in later editions of the IPA, following Jones' terminology)

It also introduced several new suprasegmental specifications:[43]

- ⟨ˎ⟩ for "half-accent"

- ⟨˝⟩ for "reinforced accent"

- Tones could be indicated either before the syllable or on the nuclear vowel: ⟨´◌, ◌́⟩ high rising, ⟨ˉ◌, ◌̄⟩ high level, ⟨ˋ◌, ◌̀⟩ high falling, ⟨ˏ◌, ◌̗⟩ low rising, ⟨ˍ◌, ◌̠⟩ low level, ⟨ˎ◌, ◌̖⟩ low falling, ⟨ˆ◌, ◌̂⟩ rise-fall, ⟨ˇ◌, ◌̌⟩ fall-rise

- Medium tones, as necessary: ⟨´◌⟩ mid rising, ⟨ˉ◌⟩ mid level, ⟨˴◌⟩ mid falling

It recommended the use of a circumflex for the Swedish grave accent, as in [ˆandən] ("the spirit").[43] It was mentioned that some authors prefer ⟨˖, ˗⟩ in place of ⟨⊢, ⊣⟩. Aspiration was marked as ⟨pʻ, tʻ, kʻ⟩ and stronger aspiration as ⟨ph, th, kh⟩.[44]

The click letters ⟨ʇ, ʖ, ʞ, ʗ⟩ were conceived by Daniel Jones. In 1960, A. C. Gimson wrote to a colleague:

Paul Passy recognized the need for letters for the various clicks in the July–August 1914 number of Le Maître Phonétique and asked for suggestions. This number, however, was the last for some years because of the war. During this interval, Professor Daniel Jones himself invented the four letters, in consultation with Paul Passy and they were all four printed in the pamphlet L'Écriture Phonétique Internationale published in 1921. The letters were thus introduced in a somewhat unusual way, without the explicit consent of the whole Council of the Association. They were, however, generally accepted from then on, and, as you say, were used by Professor Doke in 1923. I have consulted Professor Jones in this matter, and he accepts responsibility for their invention, during the period of the First World War.[45]

⟨ʇ, ʖ, ʗ⟩ would be approved by the Council in 1928.[39] ⟨ʞ⟩ would be included in all subsequent booklets,[46][47][48][49] but not in the single-page charts. They would be replaced with the Lepsius/Bleek letters in the 1989 Kiel revision.

The 1921 book was the first in the series to mention the word phoneme (phonème).[44]

1925 Copenhagen Conference and 1927 revision

In April 1925, 12 linguists led by Otto Jespersen, including IPA Secretary Daniel Jones, attended a conference in Copenhagen and proposed specifications for a standardized system of phonetic notation.[50] The proposals were largely dismissed by the members of the IPA Council.[51] Nonetheless, the following additions recommended by the Conference were approved in 1927:[52]

- ⟨ˑ⟩ could now indicate full length when there is no need to distinguish half and full length

- Straight ⟨ˈ⟩ for stress instead of the previous slanted ⟨´⟩, and ⟨ˌ⟩ for secondary stress

- ⟨◌̫⟩ for labialized and ⟨◌̪⟩ for dental

- ⟨ʈ, ɖ, ɳ, ɭ, ɽ, ʂ, ʐ⟩, with the arm moved under the letter, for retroflex consonants

- ⟨ɸ, β⟩ for bilabial fricatives, replacing ⟨ꜰ, ʋ⟩ (⟨ʋ⟩ was repurposed for the labiodental approximant)

- ⟨◌̣⟩ for more close and ⟨◌̨⟩ for more open

1928 revisions

In 1928, the following letters were adopted:[39]

- ⟨ɬ, ɮ⟩ for lateral fricatives

- ⟨ᵭ⟩, ⟨ᵶ⟩, etc. for velarization or pharyngealization (by extension from ⟨ɫ⟩)

- ⟨ƫ⟩, ⟨ᶁ⟩, ⟨ᶇ⟩, etc. for palatalized consonants

- ⟨ɓ⟩, ⟨ɗ⟩, etc. for implosives

The following letters, which had appeared in earlier editions, were repeated or formalized:[39]

- ⟨ɕ, ʑ⟩

- ⟨ƪ, ƺ⟩

- ⟨χ⟩

- ⟨ħ, ʕ⟩

- ⟨ɨ, ʉ, ɵ⟩

- ⟨ɤ⟩

- ⟨ɜ⟩

- ⟨ɒ⟩

- ⟨ɺ⟩

- ⟨ʇ, ʖ, ʗ⟩

Jones (1928) also included ⟨ɱ⟩ for a labiodental nasal, ⟨ɾ⟩ for a dental or alveolar tap, ⟨ʞ⟩ for a palatal ('velar') click, and the tonal notation system seen in Association phonétique internationale (1921), p. 9. For the Swedish and Norwegian compound tones he recommended "any arbitrarily chosen mark", with the illustration [˟andən] ("the spirit"). He used ⟨ᴜ⟩ in place of ⟨ʊ⟩.[53] Apart from ⟨ᴜ⟩ and ⟨ʞ⟩, these new specifications would be inherited in the subsequent charts and booklets. The diacritics for whispered, ⟨◌̦⟩, and for tense and lax, ⟨◌́, ◌̀⟩, were no longer mentioned.

1932 chart

An updated chart appeared as a supplement to Le Maître Phonétique in 1932.[54]

| Bi-labial | Labio- dental |

Dental and Alveolar |

Retroflex | Palato- alveolar |

Alveolo- palatal |

Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Pharyngal | Glottal | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosive | p b | t d | ʈ ɖ | c ɟ | k ɡ | q ɢ | ˀ | ||||||||

| Nasal | m | ɱ | n | ɳ | ɲ | ŋ | ɴ | ||||||||

| Lateral Fricative | ɬ ɮ | ||||||||||||||

| Lateral Non-fricative | l | ɭ | ʎ | ||||||||||||

| Rolled | r | ʀ | |||||||||||||

| Flapped | ɾ | ɽ | ʀ | ||||||||||||

| Fricative | ɸ β | f v | θ ð | s z | ɹ | ʂ ʐ | ʃ ʒ | ɕ ʑ | ç j | x ɣ | χ ʁ | ħ ʕ | h ɦ | ||

| Frictionless Continuants and Semi-vowels |

w | ɥ | ʋ | ɹ | j (ɥ) | (w) | ʁ | ||||||||

Front Central Back |

|||||||||||||||

| Close | (y ʉ u)

(ø o)

(œ ɔ)

(ɒ) |

i yɨ ʉɯ u

e øɤ o

ə

ɛ œʌ ɔ

æɐ

aɑ ɒ | |||||||||||||

| Half-close | |||||||||||||||

| Half-open | |||||||||||||||

| Open | |||||||||||||||

The vowels were now arranged in a right-angled trapezium as opposed to an isosceles trapezium, reflecting Daniel Jones's development of the Cardinal Vowel theory. A practically identical chart—with the exception of ⟨ɣ⟩—in German had appeared in Jones (1928), p. 23. The substitution of ⟨ɣ⟩ for ⟨ǥ⟩ was approved in 1931.[19]

The accompanying notes read:

Other Sounds.—Palatalized consonants: ƫ, ᶁ, etc. Velarized or pharyngealized consonants: ɫ, ᵭ, ᵴ, etc. Ejective consonants (plosives [sic] with simultaneous glottal stop): pʼ, tʼ, etc. Implosive voiced consonants: ɓ, ɗ, etc. ř fricative trill. σ, ƍ (labialized θ, ð, or s, z). ƪ, ƺ (labialized ʃ, ʒ). ʇ, ʗ, ʖ (clicks, Zulu c, q, x). ɺ (a sound between r and l). ʍ (voiceless w). ɪ, ʏ, ʊ (lowered varieties of i, y, u). ɜ (a variety of ə). ɵ (a vowel between ø and o).

Affricates are normally represented by groups of two consonants (ts, tʃ, dʒ, etc.), but, when necessary, ligatures are used (ʦ, ʧ, ʤ, etc.), or the marks ͡ or ͜ (t͡s or t͜s, etc.). c, ɟ may occasionally be used in place of tʃ, dʒ. Aspirated plosives: ph, th, etc.

Length, Stress, Pitch.— ː (full length). ˑ (half length). ˈ (stress, placed at the beginning of the stressed syllable). ˌ (secondary stress). ˉ (high level pitch); ˍ (low level); ˊ (high rising); ˏ (low rising); ˋ (high falling); ˎ (low falling); ˆ (rise-fall); ˇ (fall-rise). See Écriture Phonétique Internationale, p. 9.

Modifiers.— ˜ nasality. ˳ breath (l̥ = breathed l). ˬ voice (s̬ = z). ʻ slight aspiration following p, t, etc. ̣ specially close vowel (ẹ = a very close e). ˛ specially open vowel (ę = a rather open e). ̫ labialization (n̫ = labialized n). ̪ dental articulation (t̪ = dental t). ˙ palatalization (ż = ᶎ). ˔ tongue slightly raised. ˕ tongue slightly lowered. ˒ lips more rounded. ˓ lips more spread. Central vowels ï (= ɨ), ü (= ʉ), ë (= ə˔), ö (= ɵ), ɛ̈, ɔ̈. ˌ (e.g. n̩) syllabic consonant. ˘ consonantal vowel. ʃˢ variety of ʃ resembling s, etc.[54]

1938 chart

A new chart appeared in 1938, with a few modifications. ⟨ɮ⟩ was replaced by ⟨ꜧ⟩, which was approved earlier in the year with the compromise ⟨![]()

1947 chart

A new chart appeared in 1947, reflecting minor developments up to the point. They were:[58]

- ⟨ʔ⟩ for the glottal stop, replacing ⟨ˀ⟩

- ⟨

- ⟨ʆ, ʓ⟩ for palatalized [ʃ, ʒ]

- ⟨ɼ⟩ replacing ⟨ř⟩, approved in 1945[59]

- ⟨ƞ⟩ for the Japanese syllabic nasal

- ⟨ɧ⟩ for a combination of [x] and [ʃ]

- ⟨ɩ, ɷ⟩ replacing ⟨ɪ, ʊ⟩, approved in 1943 while condoning the use of the latter except in the Association's official publications[60]

- ⟨ƾ, ƻ⟩ as alternatives for [t͡s, d͡z]

- R-coloured vowels: ⟨eɹ⟩, ⟨aɹ⟩, ⟨ɔɹ⟩, etc., ⟨eʴ⟩, ⟨aʴ⟩, ⟨ɔʴ⟩, etc., or ⟨ᶒ⟩, ⟨ᶏ⟩, ⟨ᶗ⟩, etc.

- R-coloured [ə]: ⟨əɹ⟩, ⟨əʴ⟩, ⟨ɹ⟩, or ⟨ᶕ⟩

- ⟨◌̟, ◌˖⟩ and ⟨◌̠, ◌˗⟩ (or with serifs, as in ⟨◌I⟩) for advanced and retracted, respectively, officially replacing ⟨◌⊢, ◌⊣⟩

The word "plosives" in the description of ejectives and the qualifier "slightly" in the definitions of ⟨˔, ˕⟩ were removed.

1949 Principles

The 1949 Principles of the International Phonetic Association was the last installment in the series until it was superseded by the Handbook of the IPA in 1999.[61] It introduced some new specifications:[62]

- Inserting a hyphen between a plosive and a homorganic fricative to denote they are separately pronounced, as in ⟨t-s⟩, ⟨d-z⟩, ⟨t-ʃ⟩

- ⟨eh⟩, ⟨ah⟩, etc. or ⟨e̒⟩, ⟨a̒⟩, etc. for "vowels pronounced with 'breathy voice' (h-coloured vowels)"

- ⟨m̆b⟩, ⟨n̆d⟩, etc. "to show that a nasal consonant is very short and that the intimate combination with the following plosive counts as a single sound", in parallel to use for non-syllabic vowels

- An "arbitrarily chosen mark" such as ⟨˟⟩ or ⟨ˇ⟩ for a Swedish or Norwegian compound tone, as in [ˇandən] ("the spirit")

None of these specifications were inherited in the subsequent charts. ⟨ˌ⟩ was defined as an indicator of "medium stress".[63]

⟨ʞ⟩ was defined as a velar click, whereas previously it had been identified as the Khoekhoe click not found in Xhosa (that is, a palatal click).

In 1948, ⟨ɡ⟩ and ⟨![]()

![]()

1951 chart

The 1951 chart added ⟨ɚ⟩ as yet another alternative to an r-coloured [ə],[67] following its approval in 1950.[68] Conceived by John S. Kenyon, the letter was in itself a combination of ⟨ə⟩ and the hook for retroflex consonants approved by the IPA in 1927. Since its introduction in 1935, the letter was widely adopted by American linguists and the IPA had been asked to recognize it as part of the alphabet.[69][70]

1979 chart

In 1979, a revised chart appeared, incorporating the developments in the alphabet which were made earlier in the decade:[71]

| THE INTERNATIONAL PHONETIC ALPHABET (Revised to 1979) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

⟨ɻ⟩ for a retroflex approximant was approved in 1973. On the same occasion, ⟨š⟩, ⟨ž⟩, ⟨č⟩, and ⟨ǰ⟩ or ⟨ǧ⟩ as alternatives for [ʃ, ʒ, tʃ, dʒ] were proposed but the votes were inconclusive. Diacritics ⟨◌̢⟩ (subscript, not attached) for retroflexion, ⟨◌̮⟩ for palatalization, and ⟨◌̯⟩ for indicating non-fricative continuant were proposed but rejected.[72]

The following changes were approved in 1976:[73]

- ⟨ɶ⟩ for the rounded equivalent of [a] (taken from the accompanying text to Daniel Jones's 1956 recording of the Secondary Cardinal Vowels)[41][74]

- ⟨◌̈⟩ representing "centralized" rather than "central"

- ⟨ʰ⟩ for aspiration (though this was approved merely as an alternative to ⟨ʻ⟩, neither the latter diacritic nor the letter ⟨h⟩ succeeding a plosive were mentioned in the 1979 chart)

- ⟨◌̚⟩ for absence of audible release (omitted in the chart)

- ⟨ʘ⟩ for a bilabial click

- ⟨◌̤⟩ for breathy voice

- ⟨ɰ⟩ for a velar approximant

- Application of ⟨◌̣, ◌̨⟩ (but not ⟨◌̝ ◌˔, ◌̞ ◌˕⟩) to consonant letters to denote fricative and approximant, respectively, as in ⟨ɹ̣, ɹ̨⟩

On the same occasion, the following letters and diacritics were removed because they had "fallen into disuse":[73]

- ⟨◌̇⟩ for palatalization

- ⟨ƾ, ƻ⟩ for [t͡s, d͡z]

- ⟨ƞ⟩ for Japanese moraic nasal

- ⟨σ, ƍ, ƪ, ƺ⟩ for labialized [θ, ð, ʃ, ʒ]

- ⟨◌̢⟩ for r-colouring, as in ⟨ᶒ, ᶏ, ᶗ, ᶕ⟩

On the other hand, ⟨ɘ⟩ for the close-mid central unrounded vowel, ⟨ɞ⟩ for the open-mid central rounded vowel, and ⟨ᴀ⟩ for the open central unrounded vowel were proposed but rejected.[41][73] The proposal of ⟨ɘ, ɞ⟩ was based on Abercrombie (1967), p. 161.[75] ⟨ʝ⟩ for the voiced palatal fricative and ⟨◌̰⟩ for creaky voice were proposed but the votes were inconclusive.[73]

In the 1979 chart, ⟨ɩ, ʏ, ɷ⟩, previously defined as "lowered varieties of i, y, u", appeared slightly centered rather than simply midway between [i, y, u] and [e, ø, o] as they did in the 1912 chart. ⟨ɪ, ʊ⟩, the predecessors to ⟨ɩ, ɷ⟩, were acknowledged as alternatives to ⟨ɩ, ɷ⟩ under the section "Other symbols". ⟨ɵ⟩ appeared as the rounded counterpart to [ə] rather than between [ø] and [o].

The name of the column "Dental and alveolar" was changed to "Dental, alveolar, or post-alveolar". "Pharyngeal", "trill", "tap or flap", and "approximant" replaced "pharyngal", "rolled", "flapped", and "frictionless continuants", respectively. ⟨ɹ, ʁ⟩, which were listed twice in both the fricative and frictionless continuant rows in the previous charts, now appeared as an approximant and a fricative, respectively, while the line between the rows was erased, indicating certain fricative letters may represent approximants and vice versa, with the employment of the raised and lowered diacritics if necessary. ⟨ʍ⟩, previously defined as "voiceless w", was specified as a fricative. ⟨j⟩ remained listed twice in the fricative and approximant rows. ⟨ɺ⟩, previously defined merely as "a sound between r and l", was redefined as an alveolar lateral flap, in keeping with the use for which it had been originally approved, "a sound between l and d".

1989 Kiel Convention

By the 1980s, phonetic theories had developed so much since the inception of the alphabet that the framework of it had become outdated.[76][77][78] To resolve this, at the initiative of IPA President Peter Ladefoged, approximately 120 members of the IPA gathered at a convention held in Kiel, West Germany, in August 1989, to discuss revisions of both the alphabet and the principles it is founded upon.[10] It was at this convention that it was decided that the Handbook of the IPA (International Phonetic Association 1999) be written and published to supersede the 1949 Principles.[79]

In addition to the revisions of the alphabet, two workgroups were set up, one on computer coding of IPA characters and computer representation of individual languages, and the other on pathological speech and voice quality.[10][80] The former group concluded that each IPA character should be assigned a three-digit number for computer coding known as IPA Number, which was published in International Phonetic Association (1999), pp. 161–185. The latter devised a set of recommendations for the transcription of disordered speech based on the IPA known as the Extensions to the International Phonetic Alphabet or extIPA, which was published in 1990 and adopted by the International Clinical Phonetics and Linguistics Association, which now maintains it, in 1994.[81]

A drastically renewed chart of the alphabet reflecting decisions made at the convention appeared later in the year. Additions were:[82]

- Consonants

- ⟨ʙ⟩ for a voiced bilabial trill

- ⟨ʝ⟩ for a voiced palatal fricative, with ⟨j⟩ now standing only for the approximant

- ⟨ʟ⟩ for a voiced velar lateral approximant

- ⟨ʄ, ʛ⟩ for voiced palatal and uvular implosives

- ⟨ƥ, ƭ, ƈ, ƙ, ʠ⟩ for voiceless implosives

- ⟨ʜ, ʢ⟩ for epiglottal fricatives

- ⟨ʡ⟩ for a voiced epiglottal plosive

- ⟨ǀ, ǃ, ǁ, ǂ⟩ for dental, (post)alveolar, alveolar lateral and palatal clicks, replacing ⟨ʇ, ʖ, ʗ⟩ and obsolescent ⟨ʞ⟩ (see click letter)[83]

- Diacritics

- ⟨◌̰⟩ for creaky voice

- ⟨◌̼, ◌̺, ◌̻⟩ for linguolabial, apical, and laminal

- ⟨◌̹, ◌̜⟩ for more and less rounded, now placed under the letter

- ⟨◌̽⟩ for mid-centralized

- ⟨◌̘, ◌̙⟩ for advanced and retracted tongue root

- ⟨◌ ˞⟩ for rhoticity

- ⟨◌ʷ⟩ for labialization, replacing ⟨◌̫⟩

- ⟨◌ʲ⟩ for palatalization, replacing ⟨◌̡⟩

- ⟨◌ˠ, ◌ˤ⟩ for velarization and pharyngealization

- ⟨◌ⁿ, ◌ˡ⟩ for nasal and lateral release

- ⟨◌̯⟩ for non-syllabic, replacing ⟨◌̆⟩, which now stands for extra-short

- Suprasegmentals

- ⟨◌̆⟩, which previously stood for non-syllabic, for extra-short

- ⟨.⟩ for a syllable break

- ⟨|, ‖⟩ for minor (foot) and major (intonation) groups

- ⟨‿⟩ for linking (absence of a break)

- ⟨↗, ↘⟩ for global rise and fall of pitch

- ⟨ꜜ, ꜛ⟩ for downstep and upstep

Tone, which had been indicated with an iconic line preceding the syllable or above or below the vowel, was now written one of two ways: with a similar iconic line following the syllable and anchored to a vertical bar, as in ⟨˥, ˦, ˧˩˨⟩ (Chao's tone letters), or with more abstract diacritics written over the vowel (acute = high, macron = mid, grave = low), which could be compounded with each other, as in ⟨ə᷄, ə᷆, ə᷈, ə̋, ə̏⟩.

The palato-alveolar column was removed and ⟨ʃ, ʒ⟩ were listed alongside the postalveolars. ⟨ɹ⟩ appeared at the same horizontal position as the other alveolars rather than slightly more back as did in the previous charts. ⟨ʀ⟩ was specified as a trill rather than either a trill or flap. The alternative raised and lowered diacritics ⟨◌̣, ◌̨⟩ were eliminated in favour of ⟨◌̝, ◌̞⟩, which could now be attached to consonants to denote fricative or approximant, as in ⟨ɹ̝, β̞⟩. Diacritics for relative articulation placed next to, rather than below, a letter, namely ⟨◌˖, ◌˗, ◌I, ◌˔, ◌˕⟩, were no longer mentioned. The diacritic for no audible release ⟨◌̚⟩ was finally mentioned in the chart.

⟨ɩ, ɷ⟩ were eliminated in favour of ⟨ɪ, ʊ⟩. The letter for the close-mid back unrounded vowel was revised from ⟨![]()

![]()

![]()

⟨ʆ, ʓ⟩ for palatalized [ʃ, ʒ] and ⟨ɼ⟩ for the alveolar fricative trill were withdrawn (now written ⟨ʃʲ, ʒʲ⟩ and ⟨r̝⟩). The affricate ligatures were withdrawn. The tie bar below letters for affricates and doubly articulated consonants, as in ⟨t͜s⟩, was no longer mentioned. The practice of placing a superscript letter to indicate the resemblance to a sound, previously illustrated by ⟨ʃˢ⟩, was no longer explicitly recommended.

At the convention, proposals such as ⟨![]()

![]()

![]()

New principles

The six principles set out in 1888 were replaced by a much longer text consisting of seven paragraphs.[10] The first two paragraphs established the alphabet's purpose, namely to be "a set of symbols for representing all the possible sounds of the world's languages" and "representing fine distinctions of sound quality, making the IPA well suited for use in all disciplines in which the representation of speech sounds is required".[85] The second paragraph also said, "[p] is a shorthand way of designating the intersection of the categories voiceless, bilabial, and plosive; [m] is the intersection of the categories voiced, bilabial, and nasal; and so on",[86] refining the previous, less clearly defined principle #2 with the application of the distinctive feature theory.[87] Discouragement of diacritics was relaxed, though recommending their use be limited: "(i) For denoting length, stress and pitch. (ii) For representing minute shades of sounds. (iii) When the introduction of a single, diacritic obviates the necessity for designing a number of new symbols (as, for instance, in the representation of nasalized vowels)".[86] The principles also adopted the recommendation of enclosing phonetic transcriptions in square brackets [ ] and phonemic ones in slashes / /,[86] a practice that emerged in the 1940s.[88] The principles were reprinted in the 1999 Handbook.[89]

1993 revision

Following the 1989 revision, a number of proposals for revisions appeared in the Journal of the IPA, which were submitted to the Council of the IPA. In 1993, the Council approved the following changes:[90]

- ⟨ƥ, ƭ, ƈ, ƙ, ʠ⟩ for the voiceless implosives were withdrawn.

- The non-pulmonic consonants (ejectives and implosives) were removed from the main table and set up with the clicks in a separate section, with ⟨ʼ⟩ acknowledged as an independent modifier for ejective (therefore allowing combinations absent in the chart).

- It was noted that subdiacritics may be moved above a letter to avoid interference with a descender.

- The alternative letter for the mid central vowel ⟨ɜ⟩ was redefined as open-mid, and the one for the mid central rounded vowel ⟨ɵ⟩ as close-mid rounded. Two new vowel letters, ⟨ɘ⟩ and ⟨ʚ⟩, were added, representing close-mid unrounded and open-mid rounded, respectively.

- The right half of the cell for pharyngeal plosives was shaded, indicating the impossibility of a voiced pharyngeal plosive.

On the same occasion, it was reaffirmed that ⟨ɡ⟩ and ⟨![]()

The revised chart was now portrait-oriented. ⟨ə⟩ and ⟨ɐ⟩ were moved to the centerline of the vowel chart, indicating that they are not necessarily unrounded. The word "voiced" was removed from the definition for ⟨ʡ⟩, now simply "epiglottal plosive". "Other symbols" and diacritics were slightly rearranged. The outer stroke of the letter for a bilabial click ⟨ʘ⟩ was modified from a circle with a consistent width to the shape of uppercase O.[91]

1996 update

In 1996, it was announced that the form of the open-mid central rounded vowel in the 1993 chart, ⟨ʚ⟩, was a typographical error and should be changed to ⟨ɞ⟩, stating the latter was the form that "J. C. Catford had in mind when he proposed the central vowel changes ... in 1990", also citing Abercrombie (1967) and Catford (1977),[92] who had ⟨ɞ⟩.[93][94] However, the letter Catford had proposed for the value in 1990 was in fact ⟨ꞓ⟩ (a barred ⟨ɔ⟩), with an alternative being ⟨ʚ⟩, but not ⟨ɞ⟩.[95] Errata for Catford (1990) appeared in 1992, but the printed form was again ⟨ʚ⟩ and the errata even acknowledged that ⟨ʚ⟩ was included in Association phonétique internationale (1921), pp. 6–7, as pointed out by David Abercrombie.[96]

In the updated chart, which was published in the front matter of the 1999 Handbook of the IPA, the subsections were rearranged so that the left edge of the vowel chart appeared right beneath the palatal column, hinting at the palatal place of articulation for [i, y], as did in all pre-1989 charts, though the space did not allow the back vowels to appear beneath the velars.[97] A tie bar placed below letters, as in ⟨t͜s⟩, was mentioned again. ⟨˞⟩ was now attached to the preceding letter, as in ⟨ə˞⟩. A few illustrations in the chart were changed: ⟨a˞⟩ was added for rhoticity, and ⟨i̠, ɹ̩⟩ were replaced with ⟨e̠, n̩⟩. The examples of "high rising" and "low rising" tone contours were changed from ⟨˦˥⟩ (4–5) and ⟨˩˨⟩ (1–2) to ⟨˧˥⟩ (3–5) and ⟨˩˧⟩ (1–3), respectively. The word "etc." was dropped from the list of contours, though the 1999 Handbook would continue to use contours that did not appear on the chart.[98]

1999 Handbook

The 1999 Handbook of the International Phonetic Association was the first book outlining the specifications of the alphabet in 50 years, superseding the 1949 Principles of the IPA. It consisted of just over 200 pages, four times as long as the Principles. In addition to what was seen in the 1996 chart,[98] the book included ⟨ᵊ⟩ for mid central vowel release, ⟨ᶿ⟩ for voiceless dental fricative release, and ⟨ˣ⟩ for voiceless velar fricative release as part of the official IPA in the "Computer coding of IPA symbols" section.[99] The section also included ⟨ᶑ⟩ for a voiced retroflex implosive, noting it was "not explicitly IPA approved".[100] The book also said ⟨ᶹ⟩ "might be used" for "a secondary reduction of the lip opening accompanied by neither protrusion nor velar constriction".[101] It abandoned the 1949 Principles' recommendation of alternating ⟨![]()

21st-century developments

2005.pdf.jpg)

In 2005, ⟨ⱱ⟩ was added for the labiodental flap.[103]

In 2011, it was proposed that ⟨ᴀ⟩ be added to represent the open central unrounded vowel, but this was declined by the Council the following year.[104]

In 2012, the IPA chart and its subparts were released under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.[105]

In 2016, three versions of a revised chart dated 2015 were released online, each with the characters rendered in a different typeface (IPA Kiel/LS Uni developed by Linguist's Software, Doulos SIL, and DejaVu Sans).[106][107] No character was added or withdrawn, but some notes and the shapes of a few were slightly modified. In particular, ⟨ə˞⟩ was replaced by ⟨ɚ⟩, with a continuous, slanted stroke, and the example of a "rising–falling" tone contour was changed from ⟨˦˥˦⟩ (4–5–4) to ⟨˧˦˧⟩ (3–4–3).[107]

In 2018, another slightly modified chart in different fonts was released, this time also in TeX TIPA Roman developed by Rei Fukui, which was selected as best representing the IPA symbol set by the Association's Alphabet, Charts and Fonts committee, established the previous year.[108][109][110] The example of a "rising–falling" tone contour was again changed from ⟨˧˦˧⟩ (3–4–3) to ⟨˧˦˨⟩ (3–4–2).[108]

In 2020, another set of charts was released, with the only changes being minor adjustments in the layout, and Creative Commons icons replacing the copyright sign.[111]

Summary

Values that have been represented by different characters

| Value | 1900 | 1904 | 1912 | 1921 | 1932 | 1938 | 1947 | 1979 | 1989 | 1993 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glottal stop | ʔ | ˀ | ʔ | |||||||

| Voiceless bilabial fricative | ꜰ | ɸ | ||||||||

| Voiced bilabial fricative | ʋ | β | ||||||||

| Voiced velar fricative | ɣ | |||||||||

| Voiceless uvular fricative | ᴚ | χ | ||||||||

| Voiceless pharyngeal fricative (or Arabic ح) | ʜ | ħ | ||||||||

| Voiced pharyngeal fricative (or Arabic ع) | ꞯ | ʕ | ||||||||

| Voiceless labial–velar fricative | ʍ | ƕ | ʍ | |||||||

| Voiced alveolar lateral fricative | N/A | ɮ | ꜧ | ɮ | ||||||

| Voiced alveolar fricative trill | N/A | ř | ɼ | N/A | ||||||

| Retroflex consonants | ṭ, ḍ, etc. | ʈ, ɖ, ɳ, ɽ, ʂ, ʐ, ɭ | ʈ, ɖ, ɳ, ɽ, ʂ, ʐ, ɻ, ɭ | |||||||

| Bilabial click | N/A | |||||||||

| Dental click | N/A | ʇ | ǀ | |||||||

| Alveolar click | N/A | ʗ | ǃ | |||||||

| Alveolar lateral click | N/A | ʖ | ǁ | |||||||

| Palatal click | N/A | ʞ | N/A | ǂ | ||||||

| Value | 1900 | 1904 | 1912 | 1921 | 1932 | 1947 | 1979 | 1989 | 1993 | 1996 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Close-mid back unrounded vowel | Ɐ | |||||||||

| Close central unrounded vowel | ï | ɨ, ï | ɨ | |||||||

| Close central rounded vowel | ü | ʉ, ü | ʉ | |||||||

| Close-mid central unrounded vowel | ë | ɘ, ë | N/A | ɘ | ||||||

| Close-mid central rounded vowel | ö | ɵ, ö | ɵ | N/A | ɵ | |||||

| Open-mid central unrounded vowel | ä | ɛ̈ | ɜ, ɛ̈ | N/A | ɜ | |||||

| Open-mid central rounded vowel | ɔ̈ | ʚ, ɔ̈ | N/A | ʚ | ɞ | |||||

| Near-close (near-)front unrounded vowel | ı | ɪ | ɩ | ɩ, ɪ | ɪ | |||||

| Near-close (near-)back rounded vowel | ᴜ | ʊ | ᴜ | ʊ | ɷ | ɷ, ʊ | ʊ | |||

| Value | 1900 | 1904 | 1912 | 1921 | 1932 | 1947 | 1949 | 1951 | 1979 | 1989 | 1993 | 1996 | 2015 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aspirated | N/A | ◌ʻ, ◌h | ◌ʰ | |||||||||||

| More rounded | ◌˒ | ◌̹ | ◌̹, ◌͗ | |||||||||||

| Less rounded | ◌˓ | ◌̜ | ◌̜, ◌͑ | |||||||||||

| Advanced | ◌⊢ | N/A | ◌˖, ◌̟ | ◌̟ | ||||||||||

| Retracted | ◌⊣ | N/A | ◌˗, ◌̠, ◌I | ◌̠ | ||||||||||

| Raised (vowel) | ◌˔ | N/A | ◌̣, ◌˔, ◌̝ | ◌̝ | ||||||||||

| Raised (consonant) | N/A | ◌̣ | ||||||||||||

| Lowered (vowel) | ◌˕ | N/A | ◌̨, ◌˕, ◌̞ | ◌̞ | ||||||||||

| Lowered (consonant) | N/A | ◌̨ | ||||||||||||

| Syllabic | ◌̗ | ◌̩ | ◌̩, ◌̍ | |||||||||||

| Non-syllabic | ◌̆ | ◌̯ | ◌̯, ◌̑ | |||||||||||

| Rhoticity | N/A | ◌ɹ, ◌ʴ, ◌̢ | ◌ʴ, ◌ʵ, ◌ʶ | ◌ ˞ | ◌˞ | |||||||||

| R-coloured [ə] | N/A | əɹ, əʴ, ɹ, ᶕ | əɹ, əʴ, ɹ, ᶕ, ɚ | ɚ | ə ˞ | ə˞ | ɚ | |||||||

| Breathy voice | N/A | ◌h, ◌̒ | N/A | ◌̤ | ||||||||||

| Labialized | N/A | ◌̫ | ◌ʷ | |||||||||||

| Palatalized | N/A | ◌̇ | ◌̡ | ◌̡ , ◌̇ | ◌̡ | ◌ʲ | ||||||||

| Primary stress | ´ | ˈ | ||||||||||||

| High level | N/A | ˉ◌, ◌̄ | ◌́, ◌˦ | |||||||||||

| Mid level | N/A | ˉ◌ | N/A | ◌̄, ◌˧ | ||||||||||

| Low level | N/A | ˍ◌, ◌̠ | ◌̀, ◌˨ | |||||||||||

| High rising | N/A | ´◌, ◌́ | ◌᷄, ◌˦˥ | ◌᷄, ◌˧˥ | ||||||||||

| Low rising | N/A | ˏ◌, ◌̗ | ◌᷅, ◌˩˨ | ◌᷅, ◌˩˧ | ||||||||||

| Rising–falling | N/A | ˆ◌, ◌̂ | ◌᷈, ◌˦˥˦ | ◌᷈, ◌˧˦˧ | ◌᷈, ◌˧˦˨ | |||||||||

| Falling–rising | N/A | ˇ◌, ◌̌ | ◌᷈, ◌˨˩˨ | ◌᷈, ◌˧˨˧ | ◌᷈, ◌˧˨˦ | |||||||||

Characters that have been given different values

| Character | 1900 | 1904 | 1912 | 1921 | 1932 | 1947 | 1949 | 1979 | 1989 | 1993 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ʀ | Voiced uvular trill | Voiced uvular trill or flap | Voiced uvular trill | ||||||||

| ʜ | Voiceless pharyngeal fricative (or Arabic ح) | N/A | Voiceless epiglottal fricative | ||||||||

| ʁ | Voiced uvular fricative | Voiced uvular fricative or approximant | Voiced uvular fricative | ||||||||

| ɹ | Voiced postalveolar fricative or approximant | Postalveolar approximant | Alveolar approximant | ||||||||

| ʋ | Voiced bilabial fricative | Labiodental approximant | |||||||||

| ɺ | N/A | A sound between [r] and [l] | A sound between [d] and [l] | Alveolar lateral flap | |||||||

| ä | Open-mid central unrounded vowel | Open central unrounded vowel | Centralized open front unrounded vowel | ||||||||

| ɐ | Near-open central vowel (unroundedness implicit) | Near-open central unrounded vowel | Near-open central vowel | ||||||||

| ə | Mid central vowel (unroundedness implicit) | Mid central unrounded vowel | Mid central vowel | ||||||||

| ɜ | N/A | Open-mid central unrounded vowel | Variety of [ə] | Open-mid central unrounded vowel | |||||||

| ɵ | N/A | Close-mid central rounded vowel | Mid central rounded vowel | Close-mid central rounded vowel | |||||||

| ɪ | Near-close front unrounded vowel | N/A | Near-close near-front unrounded vowel | ||||||||

| ʏ | Near-close front rounded vowel | Near-close near-front rounded vowel | |||||||||

| ʊ | N/A | Near-close back rounded vowel | N/A | Near-close back rounded vowel | N/A | Near-close near-back rounded vowel | |||||

| ◌̜[lower-alpha 3] | Lowered | Less rounded | |||||||||

| ◌̈ | Central | Centralized | |||||||||

| ◌̆ | Non-syllabic | Extra-short | |||||||||

| ◌́ | Tense | High rising | High level | ||||||||

| ◌̀ | Lax | High falling | Low level | ||||||||

| ◌̄ | N/A | High level | Mid level | ||||||||

| ◌̌ | N/A | Fall-rise | Rising | ||||||||

| ◌̂ | N/A | Rise-fall | Falling | ||||||||

| ◌̣ | Retroflex | N/A | Raised | N/A | |||||||

See also

Notes

- ⟨œ⟩ for English is omitted in the key but nonetheless seen in transcriptions in the May 1887 article.

- To be precise, the shape of ⟨ǥ⟩ is close to ⟨

- The obsolete lowered diacritic is shown, or identified, as the left half ring ⟨◌̜⟩, now standing for less rounded, by some, and as the ogonek ⟨◌̨⟩ by others.[112]

References

- Kelly (1981).

- Ball, Howard & Miller (2018).

- International Phonetic Association (1999), pp. 194–7.

- International Phonetic Association (1999), p. 196.

- Phonetic Teachers' Association (1887a).

- Phonetic Teachers' Association (1887b).

- Phonetic Teachers' Association (1888a).

- Phonetic Teachers' Association (1888b).

- International Phonetic Association (1949), back endpaper.

- International Phonetic Association (1989a).

- Kemp (2006), p. 407.

- MacMahon (1986), pp. 35, 38 n. 20.

- Association phonétique internationale (1900b), p. 7.

- ʒ (turned ezh) is not supported by Unicode. It may be substituted with ⟨↋⟩ (turned three).

- Although ⟨ä⟩ may seem to be a typo for expected ⟨ɛ̈⟩, it was not corrected in the next edition of the IPA and so is more likely to derive from German ⟨ä⟩.

- Esling (2010), p. 681.

- Association phonétique internationale (1895).

- Association phonétique internationale (1900a).

- Association phonétique internationale (1931).

- The 1904 English edition says that ⟨ɦ⟩ is the Arabic and English voiced h -- its use for English, though Arabic has no such sound.

- The 1904 English edition describes these sounds as the "Circassian dental hiss". See [ŝ, ẑ] for details on these sounds, which do not currently have IPA support.

- Association phonétique internationale (1900b), p. 8.

- Association phonétique internationale (1900b), p. 9.

- Association phonétique internationale (1904), p. 10.

- Association phonétique internationale (1904), p. 7.

- Heselwood (2013), pp. 112–3.

- Association phonétique internationale (1904), p. 8.

- Association phonétique internationale (1904), p. 9.

- Association phonétique internationale (1904), p. 9, citing Sweet (1902), p. 37.

- Association phonétique internationale (1905).

- Association phonétique internationale (1908).

- Association phonétique internationale (1912), p. 10.

- Passy (1909).

- Association phonétique internationale (1912), p. 12.

- Association phonétique internationale (1912), p. 13.

- Association phonétique internationale (1921), p. 6.

- The typographic form of ⟨ʔ⟩, which was now sized as a full letter, was a question mark ⟨?⟩ with the dot removed.

- ⟨ɤ⟩ had the typographic form

- Association phonétique internationale (1928).

- Esling (2010), pp. 681–2.

- Wells (1975).

- Association phonétique internationale (1921), pp. 8–9.

- Association phonétique internationale (1921), p. 9.

- Association phonétique internationale (1921), p. 10.

- Breckwoldt (1972), p. 285.

- Jones (1928), p. 26.

- Jones & Camilli (1933), p. 11.

- Jones & Dahl (1944), p. 12.

- International Phonetic Association (1949), p. 14.

- Jespersen & Pedersen (1926).

- Collins & Mees (1998), p. 315.

- Association phonétique internationale (1927).

- Jones (1928), pp. 23, 25–7.

- Association phonétique internationale (1932).

- Jones (1938).

- Association phonétique internationale (1937).

- Association phonétique internationale (1938).

- Association phonétique internationale (1947).

- Jones (1945).

- Jones (1943).

- International Phonetic Association (1999), p. vii.

- International Phonetic Association (1949), pp. 15–9.

- International Phonetic Association (1949), p. 18.

- Jones (1948).

- Wells (2006).

- Jones & Ward (1969), p. 115.

- Association phonétique internationale (1952).

- Gimson (1950).

- Kenyon (1951), pp. 315–7.

- Editors of American Speech (1939).

- International Phonetic Association (1978).

- Gimson (1973).

- Wells (1976).

- Jones (1956), pp. 12–3, 15.

- McClure (1972), p. 20.

- Ladefoged & Roach (1986).

- Ladefoged (1987a).

- Ladefoged (1987b).

- International Phonetic Association (1989a), p. 69.

- International Phonetic Association (1999), pp. 165, 185.

- International Phonetic Association (1999), p. 186.

- International Phonetic Association (1989b).

- Köhler et al. (1988).

- International Phonetic Association (1989a), pp. 72, 74.

- International Phonetic Association (1989a), p. 67.

- International Phonetic Association (1989a), p. 68.

- International Phonetic Association (1999), pp. 37–8.

- Heitner (2003), p. 326 n. 6.

- International Phonetic Association (1999), pp. 159–60.

- International Phonetic Association (1993a).

- International Phonetic Association (1993b).

- Esling (1995).

- Abercrombie (1967), p. 161.

- Catford (1977), pp. 178–9.

- Catford (1990).

- International Phonetic Association (1991).

- Esling (2010), p. 697.

- International Phonetic Association (1999), p. ix.

- International Phonetic Association (1999), pp. 167, 170–1, 179.

- International Phonetic Association (1999), p. 166.

- International Phonetic Association (1999), p. 17.

- International Phonetic Association (1999), p. 19.

- Nicolaidis (2005).

- Keating (2012).

- International Phonetic Association (2012).

- Keating (2016).

- International Phonetic Association (2016).

- Keating (2018).

- International Phonetic Association (2018).

- Keating (2017).

- International Phonetic Association (2020).

- Whitley (2003), p. 84 n. 2.

Bibliography

- Abercrombie, David (1967). Elements of General Phonetics. Edinburgh University Press.

- Albright, Robert W. (1958). "The International Phonetic Alphabet: Its backgrounds and development". International Journal of American Linguistics. 24 (1). Part III.

- Association phonétique internationale (1895). "vɔt syr l alfabɛ" [Votes sur l'alphabet]. Le Maître Phonétique. 10 (1): 16–17. JSTOR 44707535.

- Association phonétique internationale (1900a). "akt ɔfisjɛl" [Acte officiel]. Le Maître Phonétique. 15 (2–3): 20. JSTOR 44701257.

- Association phonétique internationale (1900b). "Exposé des principes de l'Association phonétique internationale". Le Maître Phonétique. 15 (11). Supplement. JSTOR 44749210.

- Association phonétique internationale (1904). "Aim and Principles of the International Phonetic Association". Le Maître Phonétique. 19 (11). Supplement. JSTOR 44703664.

- Association phonétique internationale (1905). "Exposé des principes de l'Association phonétique internationale". Le Maître Phonétique. 20 (6–7). Supplement. JSTOR 44707887.

- Association phonétique internationale (1908). "Exposé des principes de l'Association phonétique internationale". Le Maître Phonétique. 23 (9–10). Supplement. JSTOR 44707916.

- Association phonétique internationale (1912). "The Principles of the International Phonetic Association". Le Maître Phonétique. 27 (9–10). Supplement. JSTOR 44707964.

- Association phonétique internationale (1921). L'Ecriture phonétique internationale : exposé populaire avec application au français et à plusieurs autres langues (2nd ed.).

- Association phonétique internationale (1927). "desizjɔ̃ dy kɔ̃sɛːj rəlativmɑ̃ o prɔpozisjɔ̃ d la kɔ̃ferɑ̃ːs də *kɔpnag" [Décisions du conseil relativement aux propositions de la conférence de Copenhague]. Le Maître Phonétique. Troisième série. 5 (18): 13–18. JSTOR 44704201.

- Association phonétique internationale (1928). "desizjɔ̃ ofisjɛl" [Décisions officielles]. Le Maître Phonétique. Troisième série. 6 (23): 51–53. JSTOR 44704266.

- Association phonétique internationale (1931). "desizjɔ̃ ofisjɛl" [Décisions officielles]. Le Maître Phonétique. Troisième série. 9 (35): 40–42. JSTOR 44704452.

- Association phonétique internationale (1932). "The International Phonetic Alphabet (revised to 1932)". Le Maître Phonétique. Troisième série. 10 (37). Supplement. JSTOR 44749172. Reprinted in MacMahon (1996), p. 830.

- Association phonétique internationale (1937). "desizjɔ̃ ofisjɛl" [Décisions officielles]. Le Maître Phonétique. Troisième série. 15 (52): 56–57. JSTOR 44704932.

- Association phonétique internationale (1938). "The International Phonetic Alphabet (revised to 1938)". Le Maître Phonétique. Troisième série. 16 (62). Supplement. JSTOR 44748188.

- Association phonétique internationale (1947). "The International Phonetic Alphabet (revised to 1947)". Le Maître Phonétique. Troisième série. 25 (88). Supplement. JSTOR 44748304. Reprinted in Albright (1958), p. 57.

- Association phonétique internationale (1952). "The International Phonetic Alphabet (revised to 1951)". Le Maître Phonétique. Troisième série. 30 (97). Front matter. JSTOR 44748475. Reprinted in MacMahon (2010), p. 270.

- Ball, Martin J.; Howard, Sara J.; Miller, Kirk (2018). "Revisions to the extIPA chart". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 48 (2): 155–164. doi:10.1017/S0025100317000147.

- Breckwoldt, G. H. (1972). "A Critical Investigation of Click Symbolism". In Rigault, André; Charbonneau, René (eds.). Proceedings of the Seventh International Congress of Phonetic Sciences. The Hague and Paris: Mouton. pp. 281–293. doi:10.1515/9783110814750-017.

- Catford, J. C. (1977). Fundamental Problems in Phonetics. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0-85224-279-4.

- Catford, J. C. (1990). "A proposal concerning central vowels". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 20 (2): 26–28. doi:10.1017/S0025100300004230.

- Collins, Beverly; Mees, Inger M. (1998). The Real Professor Higgins: The Life and Career of Daniel Jones. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-015124-3.

- Collins, Beverly; Mees, Inger M., eds. (2003). Daniel Jones: Selected Works. Volume VII: Selected Papers. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-23343-7.

- Editors of American Speech (1939). "A Petition". American Speech. 14 (3): 206–208. JSTOR 451421.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Esling, John H. (1995). "News of the IPA". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 25 (1): 48. doi:10.1017/S0025100300000207.

- Esling, John H. (2010). "Phonetic Notation". In Hardcastle, William J.; Laver, John; Gibbon, Fiona E. (eds.). The Handbook of Phonetic Sciences (2nd ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 678–702. doi:10.1002/9781444317251.ch18. ISBN 978-1-4051-4590-9.

- Gimson, A. C. (1950). "desizjɔ̃ ofisjɛl" [Décisions officielles]. Le Maître Phonétique. Troisième série. 28 (94): 40–41. JSTOR 44705333.

- Gimson, A. C. (1973). "The Association's Alphabet". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 3 (2): 60–61. doi:10.1017/S0025100300000773.

- Heselwood, Barry (2013). Phonetic Transcription in Theory and Practice. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-4073-7.

- Heitner, Reese M. (2003). "Brackets and slashes, stars and dots: understanding the notation of linguistic types". Language Sciences. 25 (4): 319–330. doi:10.1016/S0388-0001(03)00003-2.

- International Phonetic Association (1949). "The Principles of the International Phonetic Association". Le Maître Phonétique. Troisième série. 27 (91). Supplement. JSTOR i40200179. Reprinted in Journal of the International Phonetic Association 40 (3), December 2010, pp. 299–358, doi:10.1017/S0025100311000089.

- International Phonetic Association (1978). "The International Phonetic Alphabet (Revised to 1979)". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 8 (1–2). Supplement. JSTOR 44541414. Reprinted in MacMahon (2010), p. 271.

- International Phonetic Association (1989a). "Report on the 1989 Kiel Convention". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 19 (2): 67–80. doi:10.1017/S0025100300003868. JSTOR 44526032.

- International Phonetic Association (1989b). "The International Phonetic Alphabet (revised to 1989)". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 19 (2). Centerfold. doi:10.1017/S002510030000387X.

- International Phonetic Association (1991). "Errata". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 21 (1). Front matter. doi:10.1017/S0025100300005910.

- International Phonetic Association (1993a). "Council actions on revisions of the IPA". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 23 (1): 32–34. doi:10.1017/S002510030000476X.

- International Phonetic Association (1993b). "The International Phonetic Alphabet (revised to 1993)". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 23 (1). Center pages. doi:10.1017/S0025100300004746. Reprinted in MacMahon (1996), p. 822.

- International Phonetic Association (1999). Handbook of the International Phonetic Association: A Guide to the Use of the International Phonetic Alphabet. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-63751-1.

- International Phonetic Association (1 July 2012). "IPA Chart now under a Creative Commons Licence".

- International Phonetic Association (2016). "Full IPA Chart". Archived from the original on 5 March 2016.

- International Phonetic Association (2018). "IPA charts and sub-charts in four fonts". Archived from the original on 24 May 2018.

- International Phonetic Association (2020). "IPA charts and sub-charts in four fonts".

- Jespersen, Otto; Pedersen, Holger (1926). Phonetic Transcription and Transliteration: Proposals of the Copenhagen Conference, April 1925. Oxford University Press.

- Jones, Daniel (1928). "Das System der Association Phonétique Internationale (Weltlautschriftverein)". In Heepe, Martin (ed.). Lautzeichen und ihre Anwendung in verschiedenen Sprachgebieten. Berlin: Reichsdruckerei. pp. 18–27. Reprinted in Le Maître Phonétique 3, 6 (23), July–September 1928, JSTOR 44704262. Reprinted in Collins & Mees (2003).

- Jones, Daniel (1938). "desizjɔ̃ ofisjɛl" [Décisions officielles]. Le Maître Phonétique. Troisième série. 16 (61): 14–15. JSTOR 44704878.

- Jones, Daniel (1943). "desizjɔ̃ ofisjɛl" [Décisions officielles]. Le Maître Phonétique. Troisième série. 21 (80): 27–28. JSTOR 44705153.

- Jones, Daniel (1945). "desizjɔ̃ ofisjɛl" [Décisions officielles]. Le Maître Phonétique. Troisième série. 23 (83): 11–17. JSTOR 44705184.

- Jones, Daniel (1948). "desizjɔ̃ ofisjɛl" [Décisions officielles]. Le Maître Phonétique. Troisième série. 26 (90): 28–31. JSTOR 44705217.

- Jones, Daniel (1956). Cardinal Vowels Spoken by Daniel Jones: Text of Records with Explanatory Notes by Professor Jones (PDF). London: Linguaphone Institute.

- Jones, Daniel; Camilli, Amerindo (1933). "Fondamenti di grafia fonetica secondo il sistema dell'Associazione fonetica internazionale". Le Maître Phonétique. Troisième série. 11 (43). Supplement. JSTOR 44704558. Reprinted in Collins & Mees (2003).

- Jones, Daniel; Dahl, Ivar (1944). "Fundamentos de escritura fonética según el sistema de la Asociación Fonética Internacional". Le Maître Phonétique. Troisième série. 22 (82). Supplement. Reprinted in Collins & Mees (2003).

- Jones, Daniel; Ward, Dennis (1969). The Phonetics of Russian. Cambridge University Press.

- Keating, Patricia (2012). "IPA Council votes against new IPA symbol". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 42 (2): 245. doi:10.1017/S0025100312000114.

- Keating, Patricia (14 June 2017). "IPA Council establishes new committees". International Phonetic Association.

- Keating, Patricia (18 May 2018). "2018 IPA charts now posted online". International Phonetic Association.

- Kemp, Alan (2006). "Phonetic Transcription: History". In Brown, Keith (ed.). Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics. 9 (2nd ed.). Amsterdam: Elsevier. pp. 396–410. doi:10.1016/B0-08-044854-2/00015-8. ISBN 978-0-08-044854-1.

- Kelly, John (1981). "The 1847 Alphabet: an Episode of Phonotypy". In Asher, R. E.; Henderson, Eugene J. A. (eds.). Towards a History of Phonetics. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 248–264. ISBN 0-85224-374-X.

- Kenyon, John S. (1951). "Need of a uniform phonetic alphabet". Quarterly Journal of Speech. 37 (3): 311–320. doi:10.1080/00335635109381671.

- Köhler, Oswin; Ladefoged, Peter; Snyman, Jan; Traill, Anthony; Vossen, Rainer (1988). "The symbols for clicks". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 18 (2): 140–142. doi:10.1017/S0025100300003741.

- Ladefoged, Peter (1987a). "Updating the Theory". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 17 (1): 10–14. doi:10.1017/S0025100300003170.

- Ladefoged, Peter (1987b). "Proposed revision of the International Phonetic Alphabet: A conference". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 17 (1): 34. doi:10.1017/S0025100300003224.

- Ladefoged, Peter; Roach, Peter (1986). "Revising the International Phonetic Alphabet: A plan". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 16 (1): 22–29. doi:10.1017/S0025100300003078.

- Lepsius, R. (1855). Standard Alphabet for Reducing Unwritten Languages and Foreign Graphic Systems to a Uniform Orthography in European Letters. London: Seeleys.

- MacMahon, Michael K. C. (1986). "The International Phonetic Association: The first 100 years". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 16 (1): 30–38. doi:10.1017/S002510030000308X.

- MacMahon, Michael K. C. (1996). "Phonetic Notation". In Daniels, Peter T.; Bright, William (eds.). The World's Writing Systems. Oxford University Press. pp. 821–846. ISBN 0-19-507993-0.

- MacMahon, Michael K. C. (2010). "The International Phonetic Alphabet". In Malmkjaer, Kirsten (ed.). The Routledge Linguistics Encyclopedia (3rd ed.). Routledge. pp. 269–275. ISBN 978-0-415-42104-1.

- McClure, J. Derrick (1972). "A suggested revision for the Cardinal Vowel system". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 2 (1): 20–25. doi:10.1017/S0025100300000402.

- Nicolaidis, Katerina (2005). "Approval of new IPA sound: the labiodental flap". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 35 (2): 261. doi:10.1017/S0025100305002227.

- Passy, Paul (1909). "desizjɔ̃ː dy kɔ̃ːsɛːj" [Décisions du conseil]. Le Maître Phonétique. 24 (5–6): 74–76. JSTOR 44700643.

- Phonetic Teachers' Association (1887a). "lernərz kornər" [Learners' corner]. The Phonetic Teacher. 2 (13): 5–8. JSTOR 44706347.

- Phonetic Teachers' Association (1887b). "lernərz kornər" [Learners' corner]. The Phonetic Teacher. 2 (19): 46–48. JSTOR 44706366.

- Phonetic Teachers' Association (1888a). "aur alfəbits" [Our alphabets]. The Phonetic Teacher. 3 (5): 34–35. JSTOR 44707197.

- Phonetic Teachers' Association (1888b). "aur rivàizd ælfəbit" [Our revised alphabet]. The Phonetic Teacher. 3 (7–8): 57–60. JSTOR 44701189.

- Sweet, Henry (1902). A Primer of Phonetics (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Trofimov, M. V.; Jones, Daniel (1923). The Pronunciation of Russian. Cambridge University Press. Reprinted in Collins, Beverly; Mees, Inger M., eds. (2003), Daniel Jones: Selected Works, Volume V: European Languages II – Russian, London: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-23341-0.

- Wells, John C. (1975). "The Association's alphabet". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 5 (2): 52–58. doi:10.1017/S0025100300001274.

- Wells, John C. (1976). "The Association's Alphabet". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 6 (1): 2–3. doi:10.1017/S0025100300001420.

- Wells, John C. (6 November 2006). "Scenes from IPA history". John Wells’s phonetic blog. Department of Phonetics and Linguistics, University College London.

- Whitley, M. Stanley (2003). "Rhotic representation: problems and proposals". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 23 (1): 81–86. doi:10.1017/S0025100303001166.

Further reading

- Abel, James W. (1972). "Vowel-R symbolization: An historical development". Speech Monographs. 39 (1): 23–36. doi:10.1080/03637757209375735.

- Akamatsu, Tsutomu (1992). "A critique of the IPA chart (revised to 1951, 1979 and 1989)" (PDF). Contextos. 10 (19–20): 7–45.

- Akamatsu, Tsutomu (1996). "A critique of the IPA chart (revised to 1993)" (PDF). Contextos. 14 (27–28): 9–22.

- Akamatsu, Tsutomu (2003–2004). "A critique of the IPA chart (revised to 1996)" (PDF). Contextos. 21–22 (41–44): 135–149.

- Koerner, E. F. Konrad (1993). "Historiography of Phonetics: the State of the Art". Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 23 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1017/S0025100300004710.

- Roach, Peter (1987). "Rethinking phonetic taxonomy". Transactions of the Philological Society. 85 (1): 24–37. doi:10.1111/j.1467-968X.1987.tb00710.x.