Tone letter

Tone letters are letters that represent the tones of a language, most commonly in languages with contour tones.

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

Chao tone letters (IPA)

A series of iconic tone letters based on a musical staff was devised by Yuen Ren Chao in the 1920s[1] and adopted, without the stave, into the International Phonetic Alphabet. The stave was made optional in 1989 and is now nearly universal.[2] When the contours had been drawn without a staff, it was difficult to discern subtle distinction in pitch, so only nine or so possible tones were distinguished: high, medium and low level, [ˉa ˗a ˍa]; high rising and falling, [ˊa ˋa]; low rising and falling, [ˏa ˎa]; and peaking and dipping, [ˆa ˇa].

Combinations of the Chao tone letters form schematics of the pitch contour of a tone, mapping the pitch in the letter space and ending in a vertical bar. For example, [ma˨˩˦] represents the mid-dipping pitch contour of the Chinese word for horse, 馬/马 mǎ. Single tone letters differentiate up to five pitch levels: ˥ 'extra high' or 'top', ˦ 'high', ˧ 'mid', ˨ 'low', and ˩ 'extra low' or 'bottom'. No language is known to depend on more than five levels of pitch.

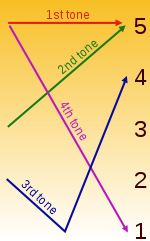

These letters are most commonly written at the end of a syllable.[3][4] For example, Standard Mandarin has the following four tones in syllables spoken in isolation:

| Tone name | Tone letter | Chao tone numerals | Tone number | Traditional Chinese | Simplified Chinese | Gloss |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High level | ma˥˥ | ma⁵⁵ | ma¹ | 媽 | 妈 | mother |

| Mid rising | ma˧˥ | ma³⁵ | ma² | 麻 | 麻 | hemp |

| Low dipping | ma˨˩˦ | ma²¹⁴ | ma³ | 馬 | 马 | horse |

| High falling | ma˥˩ | ma⁵¹ | ma⁴ | 罵 | 骂 | scold |

For languages that have simple register tones in basic morphemes, or on short vowels, single tone letters are used for these, and the tone letters combine as the tones themselves do to form contours. For example, Yoruba has the three basic tones [˥ ˧ ˩] on short vowels and the six derived contour tones [˥˧ ˥˩ ˧˥ ˧˩ ˩˧ ˩˥] on long vowels, diphthongs and contractions. On the other hand, for languages that have basic contour tones, and among these are level tones, it's conventional for double tone letters to be used for those level tones, and for single letters to be used for short checked tones, as in Taiwanese Hokkien [sã˥˥] vs [tit˥]. The tones [˥˥] and [˥] are generally analyzed as being the same phoneme, but the distinction reflects traditional Chinese classification.

Chao tones letters are sometimes written before the syllable, in accordance with writing stress and downstep before the syllable, and as had been done with the unstaffed letters in the IPA before 1989. For example, the following passage transcribes the prosody of European Portuguese using tone letters alongside stress, upstep, and downstep in the same position before the syllable:[5]

- [u ꜛˈvẽtu ˈnɔɾtɯ kumɯˈso ɐ suˈpɾaɾ kõ ˈmũitɐ ˩˧fuɾiɐ | mɐʃ ꜛˈku̯ɐ̃tu maiʃ su˩˧pɾavɐ | maiz ꜛu viɐꜜˈʒɐ̃tɯ si ɐkõʃꜜˈɡava suɐ ˧˩kapɐ | ɐˈtɛ ꜛkiu ˈvẽtu ˈnɔɾtɯ ˧˩d̥z̥ʃtiu ǁ]

- O vento norte começou a soprar com muita fúria, mas quanto mais soprava, mais o viajante se aconchegava à sua capa, até que o vento norte desistiu.

The two systems may be combined, with prosodic pitch written before a word or syllable and lexical tone after a word or syllable, since in the Sinological tradition the tone letters following a syllable are always purely lexical and disregard prosody.

Diacritics may also be used to transcribe tone in the IPA. For example, tone 3 in Mandarin is a low tone between other syllables, and can be represented as such phonemically. The four Mandarin tones can therefore be transcribed /má, mǎ, mà, mâ/. (These diacritics conflict with the conventions of Pinyin, which uses the pre-Kiel IPA diacritic conventions: ⟨mā, má, mǎ, mà⟩, respectively)

Reversed Chao tone letters

Reversed Chao tone letters indicate tone sandhi, with the left-facing letters on the left for the underlying tone, and reversed right-facing letters on the right for the surface tone. For example, the Mandarin phrase nǐ /ni˨˩˦/ + hǎo /xaʊ˨˩˦/ > ní hǎo /ni˧˥xaʊ˨˩˦/ is transcribed:

- ⫽ni˨˩˦꜔꜒xaʊ˨˩˦⫽

Such usage has been adopted by the IPA, though it does not appear in the space-limited IPA chart.[6]

The phonetic realization of neutral tones are sometimes indicated by replacing the horizontal stroke with a dot: ⟨꜌ ꜋ ꜊ ꜉ ꜈⟩. When combined with tone sandhi, the same letters may face to the right: ⟨꜑ ꜐ ꜏ ꜎ ꜍⟩.

Numerical values

Tone letters are often transliterated into numerals, particularly in Asian and Mesoamerican tone languages. Until the spread of OpenType computer fonts starting in 2000–2001, tone letters were not practical for many applications. A numerical substitute has been commonly used for tone contours, with a numerical value assigned to the beginning, end, and sometimes middle of the contour. For example, the four Mandarin tones are commonly transcribed as "ma55", "ma35", "ma214", "ma51".[7]

However, such numerical systems are ambiguous. In Asian languages such as Chinese, convention assigns the lowest pitch a 1 and the highest a 5, corresponding to fundamental frequency (f0). Conversely, in Africa the lowest tone is assigned a 5 and the highest a 1, barring a few exceptional cases with six tone levels, which may have the opposite convention of 1 being low and 6 being high. In the case of Mesoamerican languages, the highest tone is 1 but the lowest depends on the number of contrastive pitch levels in the language being transcribed. For example, an Otomanguean language with three level tones will denote them as 1 (high /˥/), 2 (mid /˧/) and 3 (low /˩/). (Three-tone systems occur in Mixtecan, Chinantecan and Amuzgoan languages.) A reader accustomed to Chinese usage will misinterpret the Mixtec low tone as mid, and the high tone as low. Because tone letters are iconic, and musical staves are internationally recognized with high tone at the top and low tone at the bottom, tone letters do not suffer from this ambiguity.

| high-level | high-falling | mid-rising | mid-level | mid-falling | mid-dipping | low-level | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tone letter | ˥ | ˥˩ | ˧˥ | ˧ | ˧˩ | ˨˩˦ | ˩ |

| Chinese convention | 55 | 51 | 35 | 33 | 31 | 214 | 11 |

| African convention | 1 | 15 | 31 | 3 | 35 | 453 | 5 |

| Mesoamerican convention (3 register tones) |

1 | 13 | 21 | 2 | 23 | 232 | 3 |

| Mesoamerican (Otomanguean) |

3 | 31 | 23 | 2 | 21 | 212 | 1 |

Division of tone space

The International Phonetic Association suggests using the tone letters to represent phonemic contrasts. For example, if a language has a single falling tone, then it should be transcribed as /˥˩/, even if this tone does not fall across the entire pitch range.[8]

For the purposes of a precise linguistic analysis there are at least three approaches: linear, exponential, and language-specific. A linear approach is to map the tone levels directly to fundamental frequency (f0), by subtracting the tone with lowest f0 from the tone with highest f0, and dividing this space into four equal f0 intervals. Tone letters are then chosen based on the f0 tone contours over this region.[9][10] This linear approach is systematic, but it does not always align the beginning and end of each tone with the proposed tone levels.[11] Chao's earlier description of the tone levels is an exponential approach. Chao proposed five tone levels, where each level is spaced two semitones apart.[3] A later description provides only one semitone between levels 1 and 2, and three semitones between levels 2 and 3.[4] This updated description may be a language-specific division of the tone space.[12]

IPA tone letters in Unicode

In Unicode, the IPA tone letters are encoded as follows:[13]

- U+02E5 ˥ MODIFIER LETTER EXTRA-HIGH TONE BAR (HTML

˥) - U+02E6 ˦ MODIFIER LETTER HIGH TONE BAR (HTML

˦) - U+02E7 ˧ MODIFIER LETTER MID TONE BAR (HTML

˧) - U+02E8 ˨ MODIFIER LETTER LOW TONE BAR (HTML

˨) - U+02E9 ˩ MODIFIER LETTER EXTRA-LOW TONE BAR (HTML

˩)

- U+A712 ꜒ MODIFIER LETTER EXTRA-HIGH LEFT-STEM TONE BAR (HTML

꜒) - U+A713 ꜓ MODIFIER LETTER HIGH TONE LEFT-STEM BAR (HTML

꜓) - U+A714 ꜔ MODIFIER LETTER MID TONE LEFT-STEM BAR (HTML

꜔) - U+A715 ꜕ MODIFIER LETTER LOW TONE LEFT-STEM BAR (HTML

꜕) - U+A716 ꜖ MODIFIER LETTER EXTRA-LOW LEFT-STEM TONE BAR (HTML

꜖)

These are combined in sequence for contour tones.

The dotted tone letters are:

- U+A708 ꜈ MODIFIER LETTER EXTRA-HIGH DOTTED TONE BAR (HTML

꜈) - U+A709 ꜉ MODIFIER LETTER HIGH DOTTED TONE BAR (HTML

꜉) - U+A70A ꜊ MODIFIER LETTER MID DOTTED TONE BAR (HTML

꜊) - U+A70B ꜋ MODIFIER LETTER LOW DOTTED TONE BAR (HTML

꜋) - U+A70C ꜌ MODIFIER LETTER EXTRA-LOW DOTTED TONE BAR (HTML

꜌)

- U+A70D ꜍ MODIFIER LETTER EXTRA-HIGH DOTTED LEFT-STEM TONE BAR (HTML

꜍) - U+A70E ꜎ MODIFIER LETTER HIGH TONE DOTTED LEFT-STEM BAR (HTML

꜎) - U+A70F ꜏ MODIFIER LETTER MID TONE DOTTED LEFT-STEM BAR (HTML

꜏) - U+A710 ꜐ MODIFIER LETTER LOW TONE DOTTED LEFT-STEM BAR (HTML

꜐) - U+A711 ꜑ MODIFIER LETTER EXTRA-LOW DOTTED LEFT-STEM TONE BAR (HTML

꜑)

Unicode includes other tone letters, such as UPA and extended tone marks for bopomofo (see).

Non-IPA systems

Although the phrase "tone letter" generally refers to the Chao system, there are also orthographies with letters assigned to individual tones, which may also be called tone letters.

In several systems, tone numbers are integrated into the orthography and so they are technically letters even though they continue to be called "numbers". However, in the case of Zhuang, the 1957 Chinese orthography modified the digits to make them graphically distinct from digits used numerically. Two letters were adopted from Cyrillic: ⟨з⟩ and ⟨ч⟩, replacing the similar-looking tone numbers ⟨3⟩ and ⟨4⟩. In 1982, these were replaced with Latin letters, one of which, ⟨h⟩, now doubles as both a consonant letter for /h/ and a tone letter for mid tone.

| Tone number |

Tone letter | Pitch number | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1957 | 1982 | IPA | ||

| 1 | ∅ | ˨˦ | 24 | |

| 2 | ƨ | z | ˧˩ | 31 |

| 3 | з | j | ˥ | 55 |

| 4 | ч | x | ˦˨ | 42 |

| 5 | ƽ | q | ˧˥ | 35 |

| 6 | ƅ | h | ˧ | 33 |

The Hmong Romanized Popular Alphabet was devised in the early 1950s with Latin tone letters. Two of the 'tones' are more accurately called register, as tone is not their distinguishing feature. Several of the letters pull double duty representing consonants.

| Tone name | Tone letter |

Example | |

|---|---|---|---|

| High | b | pob | /pɔ́/ 'ball' |

| Mid | ∅ | po | /pɔ/ 'spleen' |

| Low | s | pos | /pɔ̀/ 'thorn' |

| High falling | j | poj | /pɔ̂/ 'female' |

| Mid rising | v | pov | /pɔ̌/ 'to throw' |

| Creaky (low falling) | m | pom | /pɔ̰/ 'to see' |

| Creaky (low rising) | d | pod | |

| Breathy (mid-low) | g | pog | /pɔ̤/ 'grandmother' |

(The low-rising creaky register is a phrase-final allophone of the low-falling register.)

Also, a unified Miao alphabet used in China applies a different scheme:

| Tone number | Tone letter | IPA tone letter | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xong | Hmu | Hmong | Diandongbei Miao | ||

| 1 | b | ˧˥ | ˧ | ˦˧ | ˦˧ |

| 2 | x | ˧˩ | ˥ | ˧˩ | ˧˥ |

| 3 | d | ˦ | ˧˥ | ˥ | ˥ |

| 4 | l | ˧ | ˨ | ˨˩ | ˩ |

| 5 | t | ˥˧ | ˦ | ˦ | ˧ |

| 6 | s | ˦˨ | ˩˧ | ˨˦ | ˧˩ |

| 7 | k | ˦ | ˥˧ | ˧ | ˩ |

| 8 | f | ˧ | ˧˩ | ˩˧ | ˧˩ |

The Uralic Phonetic Alphabet has marks resembling half brackets that indicate the beginning and end of high and low tone: mid tone ˹high tone˺ ˻low tone˼.

See also

- Tone (linguistics)#Phonetic notation

- Thai alphabet#Tone

- Tone (linguistics)

- Tone contour

- Tone number

- Tone name

- Tone (disambiguation)

- Four tones (Middle Chinese) for traditional Chinese notation

Notes

- (Chao 1930)

- Most fonts display the Chao tone letters with the stave. However, a few such as Charis SIL provide an option to omit it. See Tunable feature settings in Charis SIL 5.000

- (Chao 1956)

- (Chao 1968)

- "Portuguese (European)", IPA Handbook, 1999

- Report on the 1989 Kiel Convention. Journal of the International Phonetic Association 19.2 (December 1989)

- The Mandarin high tone is usually written as "ma55" instead of as "ma5" to both avoid confusion with tone number 5, and to show this is not an "abrupt" tone.

- (International Phonetic Association 1999, p. 14)

- (Vance 1977)

- (Du 1988)

- (Cheng 1973)

- (Fon 2004)

- Unicode chart Spacing Modifying Letters (U+02B0.., pdf)

References

- Chao, Yuen-Ren (1930), "ə sistim əv "toun-letəz"" [A system of "tone-letters"], Le Maître Phonétique, 30: 24–27, JSTOR 44704341

- Chao, Yuen-Ren (1956), "Tone, intonation, singsong, chanting, recitative, tonal composition and atonal composition in Chinese.", in Halle, Moris (ed.), For Roman Jakobson, The Hague: Mouton, pp. 52–59

- Chao, Yuen-Ren (1968), A Grammar of Spoken Chinese, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press

- Cheng, Teresa M. (1973), "The Phonology of Taishan", Journal of Chinese Linguistics, 1 (2): 256–322

- Du, Tsai-Chwun (1988), Tone and Stress in Taiwanese, Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan (Ph.D. Dissertation)

- Fon, Janice; Chaing, Wen-Yu (1999), "What does Chao have to say about tones?", Journal of Chinese Linguistics, 27 (1): 13–37

- International Phonetic Association (1999), Handbook of the International Phonetic Association, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press

- Vance, Timothy J. (1977), "Tonal distinctions in Cantonese", Phonetica, 34 (2): 93–107, doi:10.1159/000259872, PMID 594156