Prehistory of the Levant

The prehistory of the Levant includes the various cultural changes that occurred, as revealed by archaeological evidence, prior to recorded traditions in the area of the Levant. Archaeological evidence suggests that Homo sapiens and other hominid species originated in Africa (see hominid dispersal) and that one of the routes taken to colonize Eurasia was through the Sinai Peninsula desert and the Levant, which means that this is one of the most important and most occupied locations in the history of the Earth. Not only have many cultures and traditions of humans lived here, but also many species of the genus Homo. In addition, this region is one of the centers for the development of agriculture.[1]

Impact of location, climate, routes

Geographically the area is divided between a coastal plain, hill country to the east and the Jordan Valley joining the Sea of Galilee to the Dead Sea. Rainfall decreases from the north to the south, with the result that the northern region of Israel has generally been more economically developed than the southern one of Judah.

At the latest from the Neolithic period onwards, the area's location at the center of three trade routes linking three continents made it the meeting place for religious and cultural influences from Egypt, Syria, Mesopotamia, and Asia Minor:

- A Coastal Route (the "Via Maris"): connecting Gaza and the Philistine coast north to Joppa and Megiddo, travelling north through Byblos to Phoenicia and Anatolia.

- A Hill Route: travelling through the Negev, Kadesh Barnea, to Hebron and Jerusalem, and thence north to Samaria, Shechem, Shiloh, Beth Shean and Hazor, and thence to Kadesh and Damascus.

- The "Kings Highway": travelling north from Eilat, east of the Jordan through Amman to Damascus, and connected to the "frankincense road" north from Yemen and South Arabia.

The area seems to have suffered from acute periods of desiccation, and reduced rainfall which has influenced the relative importance of settled versus nomadic ways of living. The cycle seems to have been repeated a number of times during which a reduced rainfall increases periods of fallow, with farmers spending increasing amounts of time with their flocks and away from cultivation. Eventually they revert to fully nomadic cultures, which, when rainfall increases settle around important sources of water and begin to spend increasing amounts of time on cultivation. The increased prosperity leads to a revival of inter-regional and eventually international trade. The growth of villages rapidly proceeds to increased prosperity of market towns and city states, which attract the attention of neighbouring great powers, who may invade to capture control of regional trade networks and possibilities for tribute and taxation. Warfare leads to opening the region to pandemics, with resultant depopulation, overuse of fragile soils and a reversion to nomadic pastoralism.

Palaeolithic period (1,400,000 - 20,000 BCE)

The earliest traces of the human occupation in the Levant are documented in Ubeidiya in the Jordan Valley of the Southern Levant, dated to the Lower Palaeolithic period, c. 1.4 million years ago.[2] The lithic assemblages relate to the Early Acheulian culture. Later Acheulian sites include Gesher Benot Ya'akov, Tabun Cave and others dated to the time span of c. 1,400,000 – c. 250,000 years ago. This layer contains the world's first signs of domesticated dogs and controlled usage of fire.[3][4] Lower Palaeolithic human remains from the Southern Levant are scarce; they include isolated teeth from 'Ubeidiya, long bone fragments from Gesher Benot Ya'akov, and a fragmentary skull from Zuttiyeh Cave ("The Galilee Man").

The Middle Palaeolithic period (c. 250,000 – c. 48,000 BCE) is represented in the Levant by the Mousterian culture, known from numerous sites (both caves and open-air sites) through the region. The chronological subdivision of the Mousterian is based on the stratigraphic sequence of the Tabun Cave. Middle Paleolithic human remains include both the Neanderthals (in Kebara Cave, Amud Cave and Tabun), and anatomically modern humans (AMH) from Jebel Qafzeh and Skhul Cave.

The Upper Palaeolithic period is dated in the Levant to c. 48,000 – c. 20,000 BCE.

Epi-Palaeolithic period (20,000 - 9,500 BCE)

Epi-Palaeolithic period (c. 20,000 – c. 9,500 cal. BCE) is characterized by significant cultural variability and wide spread of the microlithic technologies. Beginning with the appearance of the Kebaran culture (18,000–12,500 BCE) a microlithic toolkit was associated with the appearance of the bow and arrow into the area. Kebaran shows affinities with the earlier Helwan phase in the Egyptian Fayyum, and may be associated with a movement of people across the Sinai associated with the climatic warming after the Late Glacial Maxima of 20,000 BCE. Kebaran affiliated cultures spread as far as Southern Turkey. The latest part of the period (c. 12,500 – c. 9,500 cal. BCE) is the time of flourishing of the Natufian culture and development of sedentism among the hunter-gatherers.

Natufian

This Culture existed from about 13,000 to 9,800 BCE in the Levant. A lot of archaeological excavations of this culture creates a relatively well defined understanding of these people. Two of the most significant aspects of this Culture were their large community sizes and their sedentary lifestyles.[5] Although the Late Natufian experienced a slight reversal in this trend (possibly a result of the cold climatic period the Younger Dryas) as their community size shrank and they became more nomadic, it is believed that this culture continued through and was the foundation for the Neolithic Revolution.[6]

Neolithic period

Pre-Pottery and Pottery Neolithic

The Neolithic period is traditionally divided to the Pre-Pottery (A and B) and Pottery phases. PPNA developed from the earlier Natufian cultures of the area. This is the time of the agricultural transition and development of farming economies in the Near East, and the region's first known megaliths (and Earth's oldest known megalith, other than Gobekli Tepe, which is in the Northern Levant and from an unknown culture) with a burial chamber and tracking of the sun or other stars.

In addition, the Levant in the Neolithic (and later, in the Chalcolithic) was involved in large scale, far reaching trade.[7]

Chalcolithic period

Trade on an impressive scale and covering large distances continued during the Chalcolithic (c. 4500–3300 BCE). Obsidian found in the Chalcolithic levels at Gilat, Israel have had their origins traced via elemental analysis to three sources in Southern Anatolia: Hotamis Dağ, Göllü Dağ, and as far east as Nemrut Dağ, 500 km (310 mi) east of the other two sources. This is indicative of a very large trade circle reaching as far as the Northern Fertile Crescent at these three Anatolian sites.[7]

The Ghassulian period created the basis of the Mediterranean economy which has characterized the area ever since. A Chalcolithic culture, the Ghassulian economy was a mixed agricultural system consisting of extensive cultivation of grains (wheat and barley), intensive horticulture of vegetable crops, commercial production of vines and olives, and a combination of transhumance and nomadic pastoralism. The Ghassulian culture, according to Juris Zarins, developed out of the earlier Munhata phase of what he calls the "circum Arabian nomadic pastoral complex", probably associated with the first appearance of Semites in this area.

Early and Middle Bronze Age

The urban development of Canaan lagged considerably behind that of Egypt and Mesopotamia and even that of Syria, where from 3,500 BCE a sizable city developed at Hamoukar. This city, which was conquered, probably by people coming from the Southern Iraqi city of Uruk, saw the first connections between Syria and Southern Iraq that some[8][9] have suggested lie behind the patriarchal traditions. Urban development again began culminating in the Early Bronze Age development of sites like Ebla, which by 2,300 BCE was incorporated once again into an Empire of Sargon, and then Naram-Sin of Akkad (Biblical Accad). The archives of Ebla show reference to a number of Biblical sites, including Hazor, Jerusalem, and a number of people have claimed, also to Sodom and Gomorrah, mentioned in the patriarchal records. The collapse of the Akkadian Empire, saw the arrival of peoples using Khirbet Kerak Ware pottery,[10] coming originally from the Zagros Mountains, east of the Tigris. It is suspected by some that this event marks the arrival in Syria and Palestine of the Hurrians, people later known in the Biblical tradition possibly as Horites.

The following Middle Bronze Age period was initiated by the arrival of "Amorites" from Syria in Southern Iraq, an event which people like Albright (above) associated with the arrival of Abraham's family in Ur. This period saw the pinnacle of urban development in the area of Syria and Palestine. Archaeologists show that the chief state at this time was the city of Hazor, which may have been the capital of the region of Israel. This is also the period in which Semites began to appear in larger numbers in the Nile delta region of Egypt.

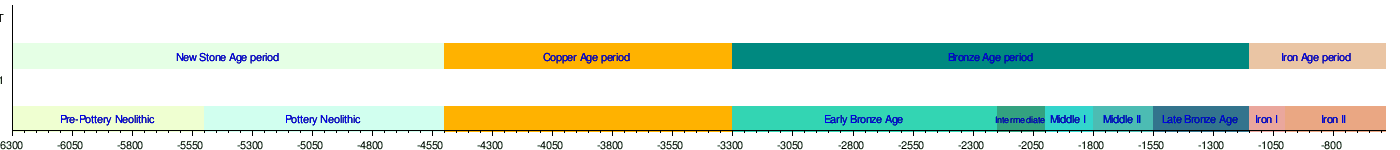

Timeline

See also

References

- Bar-Yosef, Yosef (1998). "The Natufian culture in the Levant, threshold to the origins of agriculture". Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews. 6 (5): 159–177. doi:10.1002/(sici)1520-6505(1998)6:5<159::aid-evan4>3.0.co;2-7.

- Bar-Yosef (1994). "The lower paleolithic of the Near East" (8): 211–265. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Goren-Inbar, Naama; Alperson, Nira; Kislev, Mordechai E.; Simchoni, Orit; Melamed, Yoel; Ben-Nun, Adi; Werker, Ella (30 April 2004). "Evidence of Hominin Control of Fire at Gesher Benot Ya'aqov, Israel". Science. 304 (5671): 725–727. Bibcode:2004Sci...304..725G. doi:10.1126/science.1095443. PMID 15118160.

- James Serpell, The domestic dog: its evolution, behaviour, and interactions with people, pp 10-12. Cambridge University Press, 1995, see also [Haaretz http://www.haaretz.com/travel-in-israel/tourist-tip-of-the-day/tourist-tip-237-the-prehistoric-man-museum-at-ma-ayan-baruch.premium-1.524213]

- Bar-Yosef, Ofer (1989). "The origins of sedentism and farming communities in the Levant". Journal of World Prehistory. 3 (4): 447–498. doi:10.1007/bf00975111.

- Bar-Yosef, Ofer (1998). "On the nature of transitions: the Middle to Upper Palaeolithic and the Neolithic Revolution" (PDF). Cambridge Archaeological Journal. 8 (2): 141–163. doi:10.1017/s0959774300001815.

- Yellin, Joseph; Levy, Thomas E.; Rowan, Yorke M. (1996). "New Evidence on Prehistoric Trade Routes: The Obsidian Evidence from Gilat, Israel". Journal of Field Archaeology. 23 (3): 361–368. doi:10.1179/009346996791973873.

- Bright, John (2000)"A History of Israel" (John Knox Press Westminster)

- Albright, William F. "From Abraham to Ezra"

- "See". Archived from the original on 2008-02-24. Retrieved 2007-02-26.

External links

- Joel Ng, Introduction to Biblical Archaeology 2: From Stone to Bronze

- Paul James Cowie, Archaeowiki: Archaeology of the Southern Levant