Artaxerxes III

Ochus (Greek: Ὦχος, Ôchos; Babylonian: Ú-ma-kuš), better known by his dynastic name of Artaxerxes III (Old Persian: 𐎠𐎼𐎫𐎧𐏁𐏂 Artaxšaçā) was King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire from 358 to 338 BC. He was the son and successor of Artaxerxes II (r. 404 – 358 BC) and his mother was Stateira.

| Artaxerxes III 𐎠𐎼𐎫𐎧𐏁𐏂 | |

|---|---|

| King of Kings Great King King of Persia Pharaoh of Egypt King of Countries | |

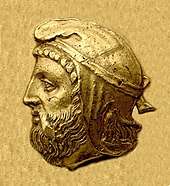

Bust of Artaxerxes III, located in the Allard Pierson Museum in the Netherlands | |

| King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire | |

| Reign | 358 – 338 BC |

| Predecessor | Artaxerxes II |

| Successor | Arses |

| Pharaoh of Egypt | |

| Reign | 343 – 338 BC |

| Predecessor | Nectanebo II |

| Successor | Arses |

| Died | August/September 338 BC |

| Burial | |

| Issue | Arses Parysatis II |

| Dynasty | Achaemenid |

| Father | Artaxerxes II |

| Mother | Stateira |

| Religion | Zoroastrianism |

Before ascending the throne Artaxerxes was a satrap and commander of his father's army. Artaxerxes came to power after one of his brothers was executed, another committed suicide, the last murdered and his father, Artaxerxes II died. Soon after becoming king, Artaxerxes murdered all of the royal family to secure his place as king. He started two major campaigns against Egypt. The first campaign failed, and was followed up by rebellions throughout the western part of his empire. In 343 BC, Artaxerxes defeated Nectanebo II, the Pharaoh of Egypt, driving him from Egypt, stopping a revolt in Phoenicia on the way.

In Artaxerxes' later years, Philip II of Macedon's power was increasing in Greece, where he tried to convince the Greeks to revolt against the Achaemenid Empire. His activities were opposed by Artaxerxes, and with his support, the city of Perinthus resisted a Macedonian siege.

There is evidence for a renewed building policy at Persepolis in his later life, where Artaxerxes erected a new palace and built his own tomb, and began long-term projects such as the Unfinished Gate.

Etymology

Artaxerxes is the Latin form of the Greek Artaxerxes (Αρταξέρξης), itself from the Old Persian Artaxšaçā ("whose reign is through truth").[1] His personal name was Ochus (Greek: Ôchos, Babylonian: Ú-ma-kuš).[2]

Early life and accession

Before ascending the throne Artaxerxes had been a satrap and commander of his father's army.[3] In 359 BC, just before ascending the throne, he attacked Egypt as a reaction to Egypt's failed attacks on coastal regions of Phoenicia.[4] In 358 BC his father, Artaxerxes II, died, it was said to be because of a broken heart caused by his children's behaviour, and, since his other sons, Darius, Ariaspes and Tiribazus had already been eliminated by plots, Artaxerxes III succeeded him as king.[5] His first order was the execution of over 80 of his nearest relations to secure his place as king.[6]

In 355 BC, Artaxerxes forced Athens to conclude a peace which required the city's forces to leave Anatolia and to acknowledge the independence of its rebellious allies.[7] Artaxerxes started a campaign against the rebellious Cadusii, but he managed to appease both of the Cadusian kings. One individual who successfully emerged from this campaign was Darius Codomannus, who later occupied the Persian throne as Darius III.

Revolt of Artabazos and Orontes against the Achaemenid King (354-353 BC)

Artaxerxes then ordered the disbanding of all the satrapal armies of Asia Minor, as he felt that they could no longer guarantee peace in the west and was concerned that these armies equipped the western satraps with the means to revolt.[8] The order was however ignored by Artabazus II, satrap of Hellespontine Phrygia, who asked for the help of Athens in a rebellion against the king. Athens sent assistance. Artabazos was at first supported by Chares, an Athenian general, and his mercenaries, whom he rewarded very generously. The gold coinage of Artabazos is thought to have been issued specifically to reward the troops of Chares. The Satrap of Mysia, Orontes I also supported Artabazus. Later, Artabazos was also supported by the Thebans, who sent him 5,000 men under Pammenes. With the assistance of these and other allies, Artabazos defeated the King in two great battles in 354 BC.

However, in 353 BC, they were defeated by Artaxerxes’ army and were disbanded. Orontes was pardoned by the king, while Artabazus fled with his family to the safety of the court of Philip II of Macedon, where he remained from 352 to 342.[9]

First Egyptian Campaign (351 BC)

In around 351 BC, Artaxerxes embarked on a campaign to recover Egypt, which had revolted under his father, Artaxerxes II. At the same time a rebellion had broken out in Asia Minor, which, being supported by Thebes, threatened to become serious.[10] Levying a vast army, Artaxerxes marched into Egypt, and engaged Nectanebo II. After a year of fighting the Egyptian Pharaoh, Nectanebo inflicted a crushing defeat on the Persians with the support of mercenaries led by the Greek generals: the Athenian Diophantus and the Spartan Lamius.[11][12] Artaxerxes was compelled to retreat and postpone his plans to reconquer Egypt.

Rebellion of Cyprus and Sidon

Soon after this Egyptian defeat, Phoenicia, Anatolia and Cyprus declared their independence from Persian rule. In 343 BC, Artaxerxes committed responsibility for the suppression of the Cyprian rebels to Idrieus, prince of Caria, who employed 8000 Greek mercenaries and forty triremes, commanded by Phocion the Athenian, and Evagoras, son of the elder Evagoras, the Cypriot monarch.[13][14] Idrieus succeeded in reducing Cyprus.

Sidon campaign of Belesys and Mazaeus

Artaxerxes initiated a counter-offensive against Sidon by commanding the satrap of Syria Belesys and Mazaeus, the satrap of Cilicia, to invade the city and to keep the Phoenicians in check.[15] Both satraps suffered crushing defeats at the hands of Tennes, the Sidonese king, who was aided by 40,000 Greek mercenaries sent to him by Nectanebo II and commanded by Mentor of Rhodes. As a result, the Persian forces were driven out of Phoenicia.[14]

Sidon campaign of Artaxerxes

After this, Artaxerxes personally led an army of 330,000 men against Sidon. Artaxerxes' army comprised 300,000 foot soldiers, 30,000 cavalry, 300 triremes, and 500 transports or provision ships. After gathering this army, he sought assistance from the Greeks. Though refused aid by Athens and Sparta, he succeeded in obtaining a thousand Theban heavy-armed hoplites under Lacrates, three thousand Argives under Nicostratus, and six thousand Æolians, Ionians, and Dorians from the Greek cities of Anatolia. This Greek support was numerically small, amounting to no more than 10,000 men, but it formed, together with the Greek mercenaries from Egypt who went over to him afterwards, the force on which he placed his chief reliance, and to which the ultimate success of his expedition was mainly due.

The approach of Artaxerxes sufficiently weakened the resolution of Tennes that he endeavoured to purchase his own pardon by delivering up 100 principal citizens of Sidon into the hands of the Persian king, and then admitting Artaxerxes within the defences of the town. Artaxerxes had the 100 citizens transfixed with javelins, and when 500 more came out as supplicants to seek his mercy, Artaxerxes consigned them to the same fate. Sidon was then burnt to the ground, either by Artaxerxes or by the Sidonian citizens. Forty thousand people died in the conflagration.[14] Artaxerxes sold the ruins at a high price to speculators, who calculated on reimbursing themselves by the treasures which they hoped to dig out from among the ashes.[16] Tennes was later put to death by Artaxerxes.[17] Artaxerxes later sent Jews who supported the revolt to Hyrcania, on the south coast of the Caspian Sea.[18][19]

Second Egyptian Campaign (343 BC)

The reduction of Sidon was followed closely by the invasion of Egypt. In 343 BC, Artaxerxes, in addition to his 330,000 Persians, had now a force of 14,000 Greeks furnished by the Greek cities of Asia Minor: 4,000 under Mentor, consisting of the troops which he had brought to the aid of Tennes from Egypt; 3,000 sent by Argos; and 1000 from Thebes. He divided these troops into three bodies, and placed at the head of each a Persian and a Greek. The Greek commanders were Lacrates of Thebes, Mentor of Rhodes and Nicostratus of Argos while the Persians were led by Rhossaces, Aristazanes, and Bagoas, the chief of the eunuchs. Nectanebo II resisted with an army of 100,000 of whom 20,000 were Greek mercenaries. Nectanebo II occupied the Nile and its various branches with his large navy. The character of the country, intersected by numerous canals, and full of strongly fortified towns, was in his favour and Nectanebo II might have been expected to offer a prolonged, if not even a successful, resistance. But he lacked good generals, and over-confident in his own powers of command, he was able to be out-manoeuvred by the Greek mercenary generals and his forces eventually defeated by the combined Persian armies.[14]

After his defeat, Nectanebo hastily fled to Memphis, leaving the fortified towns to be defended by their garrisons. These garrisons consisted of partly Greek and partly Egyptian troops; between whom jealousies and suspicions were easily sown by the Persian leaders. As a result, the Persians were able to rapidly reduce numerous towns across Lower Egypt and were advancing upon Memphis when Nectanebo decided to quit the country and flee southwards to Ethiopia.[14] The Persian army completely routed the Egyptians and occupied the Lower Delta of the Nile. Following Nectanebo fleeing to Ethiopia, all of Egypt submitted to Artaxerxes. The Jews in Egypt were sent either to Babylon or to the south coast of the Caspian Sea, the same location that the Jews of Phoenicia had earlier been sent.

After this victory over the Egyptians, Artaxerxes had the city walls destroyed, started a reign of terror, and set about looting all the temples. Persia gained a significant amount of wealth from this looting. Artaxerxes also raised high taxes and attempted to weaken Egypt enough that it could never revolt against Persia. For the 10 years that Persia controlled Egypt, believers in the native religion were persecuted and sacred books were stolen.[21] Before he returned to Persia, he appointed Pherendares as satrap of Egypt. With the wealth gained from his reconquering Egypt, Artaxerxes was able to amply reward his mercenaries. He then returned to his capital having successfully completed his invasion of Egypt.

Later years

After his success in Egypt, Artaxerxes returned to Persia and spent the next few years effectively quelling insurrections in various parts of the Empire so that a few years after his conquest of Egypt, the Persian Empire was firmly under his control. Egypt remained a part of the Persian Empire until Alexander the Great's conquest of Egypt.

After the conquest of Egypt, there were no more revolts or rebellions against Artaxerxes. Mentor of Rhodes and Bagoas, the two generals who had most distinguished themselves in the Egyptian campaign, were advanced to posts of the highest importance. Mentor, who was governor of the entire Asiatic seaboard, was successful in reducing to subjection many of the chiefs who during the recent troubles had rebelled against Persian rule. In the course of a few years Mentor and his forces were able to bring the whole Asian Mediterranean coast into complete submission and dependence.

Bagoas went back to the Persian capital with Artaxerxes, where he took a leading role in the internal administration of the Empire and maintained tranquility throughout the rest of the Empire. During the last six years of the reign of Artaxerxes III, the Persian Empire was governed by a vigorous and successful government.[14]

The Persian forces in Ionia and Lycia regained control of the Aegean and the Mediterranean Sea and took over much of Athens’ former island empire. In response, Isocrates of Athens started giving speeches calling for a ‘crusade against the barbarians’ but there was not enough strength left in any of the Greek city-states to answer his call.[22]

Although there weren't any rebellions in the Persian Empire itself, the growing power and territory of Philip II of Macedon in Macedon (against which Demosthenes was in vain warning the Athenians) attracted the attention of Artaxerxes. In response, he ordered that Persian influence was to be used to check and constrain the rising power and influence of the Macedonian kingdom. In 340 BC, a Persian force was dispatched to assist the Thracian prince, Cersobleptes, to maintain his independence. Sufficient effective aid was given to the city of Perinthus that the numerous and well-appointed army with which Philip had commenced his siege of the city was compelled to give up the attempt.[14] By the last year of Artaxerxes' rule, Philip II already had plans in place for an invasion of the Persian Empire, which would crown his career, but the Greeks would not unite with him.[23]

In 338 BC Artaxerxes III was according to a Greek source, Diodorus of Sicily, poisoned by Bagoas with the assistance of a physician.[24][25] A cuneiform tablet in the British Museum (BM 71537) however suggests Artaxerxes III died from natural causes.[26]

Legacy

Historically, kings of the Achaemenid Empire were followers of Zoroaster or heavily influenced by Zoroastrian ideology. The reign of Artaxerxes II saw a revival of the cult of Anahita and Mithra, when in his building inscriptions he invoked Ahura Mazda, Anahita and Mithra and even set up statues of his gods.[27] Mithra and Anahita had until then been neglected by true Zoroastrians—they defied Zoroaster’s command that God was to be represented only by the flames of a sacred fire.[17] Artaxerxes III is thought to have rejected Anahita and worshipped only Ahuramazda and Mithra.[28] An ambiguity in the cuneiform script of an inscription of Artaxerxes III at Persepolis suggests that he regarded the father and the son as one person, suggesting that the attributes of Ahuramazda were being transferred to Mithra. Strangely, Artaxerxes had ordered that statues of the goddess Anâhita be erected at Babylon, Damascus and Sardis, as well as at Susa, Ecbatana and Persepolis.[29]

Artaxerxes' name appears on silver coins (modeled on Athenian ones) issued while he was in Egypt. The reverse bears an inscription in an Egyptian script, saying "Artaxerxes Pharaoh. Life, Prosperity, Wealth".[30]

In literature

It is thought by some that the Book of Judith could have been originally based on Artaxerxes' campaign in Phoenicia, as Holofernes was the name of the brother of the Cappadocian satrap Ariarathes, the vassal of Artaxerxes. Bagoas, the general that finds Holofernes dead, was one of the generals of Artaxerxes during his campaign against Phoenicia and Egypt.[31][32]

Construction

There is evidence for a renewed building policy at Persepolis, but some of the buildings were unfinished at the time of his death. Two of his buildings at Persepolis were the Hall of Thirty-Two Columns, the purpose of which is unknown, and the palace of Artaxerxes III. The unfinished Army Road and Unfinished Gate, which connected the Gate of All Nations and the One-hundred Column Hall, gave archaeologists an insight into the construction of Persepolis.[10] In 341 BC, after Artaxerxes returned to Babylon from Egypt, he apparently proceeded to build a great Apadana whose description is present in the works of Diodorus Siculus.

The Nebuchadnezzar II palace in Babylon was expanded during the reign of Artaxerxes III.[33] Artaxerxes' tomb was cut into the mountain behind the Persepolis platform, next to his father's tomb.

Family

Artaxerxes III was the son of Artaxerxes II and Statira. Artaxerxes II had more than 115 sons by many wives, most of them however were illegitimate. Some of Ochus' more significant siblings were Rodogune, Apama, Sisygambis, Ocha, Darius and Ariaspes, most of whom were murdered soon after his ascension.[22]

His children were:

By Atossa.[34]

By an unknown wife:

- Bisthanes

- Parysatis II, future wife of Alexander the Great.[10]

- Sisygambis maybe was his daughter, or of Ostanes or of an Uxian leader. Her son was Darius III.

He also married:

- An unknown daughter of his sister Ocha.[35]

- A daughter of Oxyathres, brother of Darius III[35][36][37]

References

- Schmitt 1986b, pp. 654-655.

- Schmitt 1986a, pp. 658-659.

- Grabbe, Lester L. (2004). A History of the Jews and Judaism in the Second Temple Period. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 323. ISBN 0-567-08998-3.

- Lipschits, Oded (2007). Garry N. Knoppers, Rainer Albertz (ed.). Judah and the Judeans in the Fourth Century B.C.E.. EISENBRAUNS. pp. 87. ISBN 978-1-57506-130-6.

- Rhodes, Peter J. (2006). A History of the Classical Greek World: 478–323 BC. Blackwell Publishing. p. 224. ISBN 0-631-22564-1. Retrieved September 24, 2016.

- Lemprière, John; R. Willets (1984) [1788]. Classical Dictionary containing a full Account of all the Proper Names mentioned in Ancient Authors. Routledge. p. 82. ISBN 0-7102-0068-4.

- Kjeilen, Tore. "Artaxerxes 3". Archived from the original on February 25, 2008. Retrieved March 5, 2008.

- Sekunda, Nick; Nicholas V. Sekunda; Simon Chew (1992). The Persian Army 560–330 BC: 560–330 BC. Osprey Publishing. pp. 28. ISBN 1-85532-250-1.

- Carney, Elizabeth Donnelly (2000). Women and Monarchy in Macedonia. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 101. ISBN 9780806132129.

- Artaxerxes III PersianEmpire.info History of the Persian Empire

- Miller, James M. (1986). A History of Ancient Israel and Judah. John Haralson Hayes (photographer). Westminster John Knox Press. pp. 465. ISBN 0-664-21262-X.

- Ruzicka, Stephen (2012). Trouble in the West: Egypt and the Persian Empire, 525-332 BC. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 161. ISBN 9780199766628.

- Newton, Sir Charles Thomas; R.P. Pullan (1862). A History of Discoveries at Halicarnassus, Cnidus & Branchidæ. Day & son. pp. 57.

- "Artaxerxes III Ochus ( 358 BC to 338 BC )". Retrieved March 2, 2008.

- Heckel, Waldemar (2008). Who's Who in the Age of Alexander the Great: Prosopography of Alexander's Empire. John Wiley & Sons. p. 172. ISBN 9781405154697.

- Rawlinson, George (1889). "Phœnicia under the Persians". History of Phoenicia. Longmans, Green. Archived from the original on July 20, 2006. Retrieved March 10, 2008.

- Meyer, Eduard (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 2 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 661–663.

- "The Legend Of Gog And Magog". Archived from the original on March 15, 2008. Retrieved March 10, 2008.

- Bruce, Frederick Fyvie (1990). The Acts of the Apostles: The Greek Text with Introduction and Commentary. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 117. ISBN 0-8028-0966-9.

- Kovacs, Frank L. (2002). "Two Persian Pharaonic Portraits". Jahrbuch für Numismatik und Geldgeschichte. R. Pflaum. pp. 55–60.

- "Persian Period II". Archived from the original on February 17, 2008. Retrieved March 6, 2008.

- "Chapter V: Temporary Relief". Archived from the original on June 19, 2008. Retrieved March 1, 2008.

- "Philip of Macedon Philip II of Macedon Biography". Archived from the original on March 14, 2008. Retrieved March 7, 2008.

- Briant, Pierre (2002). From Cyrus to Alexander: A history of the Persian Empire. Eienbrauns. pp. 769. ISBN 1-57506-120-1.

- Diod. 17.5.3

- "Collection online - Museum number 71537". The British Museum. Retrieved December 19, 2017.

- J. Varza; Dr. M. Soroushian. "The Achaemenians, Zoroastrians in Transition". Archived from the original on March 26, 2008. Retrieved March 5, 2008.

- Hans-Peter Schmidt (January 14, 2006). "i. Mithra In Old Indian And Mithra In Old Iranian". Archived from the original on March 3, 2008. Retrieved March 5, 2008.

- "The Origins Of Mithraism". Archived from the original on February 7, 2008. Retrieved March 5, 2008.

- "Silver tetradrachm of Artaxerxes III". Retrieved March 24, 2018.

- Lare, Gerald A. "The Period of Jewish Independence". Archived from the original on February 25, 2008. Retrieved March 10, 2008.

- Paul Ingram. "The Book of Judith". Retrieved March 10, 2008.

- Wigoder, Geoffrey (2006). The Illustrated Dictionary & Concordance of the Bible. Sterling Publishing Company. p. 131. ISBN 1-4027-2820-4.

- LeCoq 1986, p. 548.

- Brosius, Maria (1996). Women in Ancient Persia, 559–331 BC. Oxford University Press. p. 67. ISBN 0-19-815255-8.

- Curtius Rufus 3.13.13

- "Artaxerxes III". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved July 14, 2019.

Bibliography

Ancient works

- Arrian, The Anabasis of Alexander.

- Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca historica.

- Justin, Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus.

Modern works

- Briant, Pierre (2002). From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire. Eisenbrauns. pp. 1–1196. ISBN 9781575061207.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brosius, Maria (2000). "WOMEN i. In Pre-Islamic Persia". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. London et al.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- LeCoq, P. (1986). "Arses". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, Fasc. 5. p. 548.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schmitt, R. (1986a). "Artaxerxes III". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, Fasc. 6. pp. 658–659.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schmitt, R. (1986b). "Artaxerxes". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, Fasc. 6. pp. 654–655.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Artaxerxes III. |

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: Iranian History/The Era of the Three Dariuses |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

Artaxerxes III Born: c. 425 BC Died: 338 BC | ||

| Preceded by Artaxerxes II |

Great King (Shah) of Persia 358–338 BC |

Succeeded by Artaxerxes IV Arses |

| Preceded by Nectanebo II |

Pharaoh of Egypt XXXI Dynasty 343–338 BC | |