Tulunids

The Tulunids (Arabic: الطولونيون), were a mamluk dynasty of Turkic origin[1] who were the first independent dynasty to rule Egypt, as well as much of Syria, since the Ptolemaic dynasty.[2] They remained independent from 868, when they broke away from the central authority of the Abbasid dynasty that ruled the Islamic Caliphate, until 905, when the Abbasids restored the Tulunid domains to their control.

Ṭūlūnids طولونيون (ar) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 868–905 | |||||||||

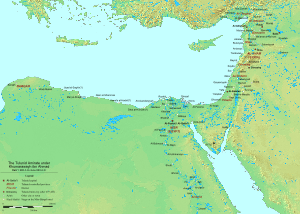

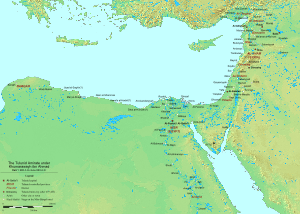

Tulunid Emirate in 893 | |||||||||

| Status | Vassal of the Abbasid Caliphate | ||||||||

| Capital | Al-Qata'i | ||||||||

| Common languages | Arabic (predominant), Turkic (army) | ||||||||

| Religion | Islam (predominant), Coptic Christians | ||||||||

| Government | Emirate | ||||||||

| Emir | |||||||||

• 868–884 | Aḥmad ibn Ṭūlūn | ||||||||

• 884–896 | Khumarawaih ibn Ahmad ibn Tulun | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Established | 868 | ||||||||

• Abbasid reconquest | 905 | ||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

| 900 (estimate) | 1,500,000 km2 (580,000 sq mi) | ||||||||

| Currency | Dinar | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| History of the Turkic peoples pre-14th century |

|---|

History of the Turkic peoples |

| Tiele people |

| Göktürks |

|

| Khazar Khaganate 618–1048 |

| Xueyantuo 628–646 |

| Kangar union 659–750 |

| Turk Shahi 665-850 |

| Türgesh Khaganate 699–766 |

| Kimek confederation 743–1035 |

| Uyghur Khaganate 744–840 |

| Oghuz Yabgu State 750–1055 |

| Karluk Yabgu State 756–940 |

| Kara-Khanid Khanate 840–1212 |

| Ganzhou Uyghur Kingdom 848–1036 |

| Qocho 856–1335 |

| Pecheneg Khanates 860–1091 |

| Ghaznavid Empire 963–1186 |

| Seljuk Empire 1037–1194 |

| Cumania 1067–1239 |

| Khwarazmian Empire 1077–1231 |

| Kerait Khanate 11th century–13th century |

| Delhi Sultanate 1206–1526 |

| Qarlughid Kingdom 1224–1266 |

| Golden Horde 1240s–1502 |

| Mamluk Sultanate (Cairo) 1250–1517 |

In the late 9th century, internal conflict amongst the Abbasids meant that control of the outlying areas of the empire was increasingly tenuous, and in 868 the Turkic officer Ahmad ibn Tulun established himself as an independent governor of Egypt. He subsequently achieved nominal autonomy from the central Abbasid government. During his reign (868–884) and those of his successors, the Tulunid domains were expanded to include Jordan Rift Valley, as well as Hejaz, Cyprus and Crete. Ahmad was succeeded by his son Khumarawayh, whose military and diplomatic achievements made him a major player in the Middle Eastern political stage. The Abbasids affirmed their recognition of the Tulunids as legitimate rulers, and the dynasty's status as vassals to the caliphate. After Khumarawayh's death, his successor emirs were ineffectual rulers, allowing their Turkic and black slave-soldiers to run the affairs of the state. In 905, the Tulunids were unable to resist an invasion by the Abbasid troops, who restored direct caliphal rule in Syria and Egypt.[3][4]

The Tulunid period was marked by economic and administrative reforms alongside cultural ones. Ahmad ibn Tulun changed the taxation system and aligned himself with the merchant community. He also established the Tulunid army. The capital was moved from Fustat to al-Qata'i, where the celebrated mosque of Ibn Tulun was constructed.

History

The rise and fall of the Tulunids occurred against a backdrop of increasing regionalism in the Muslim world. The Abbasid caliphate was struggling with political disturbances and losing its aura of universal legitimacy. There had previously been Coptic and Shia Alid-led movements in Egypt and Baghdad, without more than temporary and local success. There was also a struggle for power between the Turkish military command and the administration of Baghdad. Furthermore, there was a widening imperial financial crisis. All of these themes would recur during the Tulunid rule.[4]

The internal politics of the Abbasid caliphate itself seem to have been unstable. In 870, Abū Aḥmad (b. al-Mutawakkil) al-Muwaffaḳ (d. 891) was summoned from exile in Mecca to re-establish Abbasid authority over southern Iraq. Quickly, however, he became the de facto ruler of the caliphate. As a result of this uncertainty, Ahmad ibn Tulun could establish and expand his authority. Thus the Tulunids wielded regional power, largely unhindered by imperial will; as such, the Tulunids can be compared with other 9th-century dynasties of the Muslim world, including the Aghlabids and the Tahirids.[4]

Ahmad ibn Tulun

Ahmad ibn Ṭūlūn was a member of the mostly Central Asian Turkish guard formed initially in Baghdad, then later settled in Samarra, upon its establishment as the seat of the caliphate by al-Mu'tasim. In 254/868,[5] Ibn Tulun was sent to Egypt as resident governor by Bāyakbāk (d. 256/870), the representative of the Abbasid caliph al-Muʿtazz.[4] Ibn Tulun promptly established a financial and military presence in the province of Egypt by establishing an independent Egyptian army and taking over the management of the Egyptian and Syrian treasuries. In 877, troops of the caliphate were sent against him, due to his insufficient payment of tribute. Ahmad ibn Tulun, however, maintained his power, and took Syria the following year.[3]

His reign of more than ten years allowed him to leave behind a well-trained military, a stable economy and an experienced bureaucracy to oversee the state affairs. He appointed his son, Ḵh̲umārawayh, as the heir.[4]

With full autonomy, once the tax income no longer had to go to the Caliph in Baghdad, it was possible to develop irrigation works and build a navy, which greatly stimulated the local economy and trade. In 878, the Jordan valley was occupied by the Tulunids, extending in the north to the outposts in the Anti-Lebanon mountains on the Byzantine border, enabling them to defend Egypt against Abbasid attack.[6]

Khumarawayh

Following his father's death, Khumarawayh took control as the designated heir. The first challenge he faced was the invasion of Syria by armies sent by al-Muwaffak, the de facto ruler during the reign of caliph al-Mu'tamid. Khumarawayh also had to deal with the defection of Ahmad ibn Muhammad al-Wasiti, a long-time and key ally of his father's, to the invaders' camp.[4]

The young Tulunid achieved political and military gains, enabling him to extend his authority from Egypt into northern Iraq, and as far north as Tarsus by 890. Being now a prominent player in the Near Eastern political stage, he negotiated two treaties with the Abbasids. In the first treaty in 886, al-Muwaffak recognized Tulunid authority over Egypt and the regions of Syria for a thirty-year period. The second treaty, reached with al-Muʿtadid in 892, confirmed the terms of the earlier accord. Both treaties also sought to confirm the status of the Tulunid governor as a vassal of the caliphal family seated in Baghdad.[4]

Despite his gains, Khumarawayh's reign also set the stage for the demise of the dynasty. Financial exhaustion, political infighting and strides by the Abbasids would all contribute to the ruin of the Tulunids.[4] Khumarawayh was also totally reliant on his Turkish and sub-Saharan soldiers. Under the administration of Khumarawayh, the Syro-Egyptian state's finances and military were destabilized.[3]

Demise

The later emirs of the dynasty were all ineffectual rulers, relying on their Turkish and black soldiers to run the affairs of the state.[3]

Khumarawayh's son Abu 'l-Asakir (also known as Jaysh) was deposed by the Tulunid military command in 896 AD, shortly after coming to power. He was succeeded by his brother, Harun. Though he would rule for eight years, he was unable to revitalize the dynasty, and was assassinated in 904, after the Abbasid army had recovered Syria and was on the verge of invading Egypt itself. Harun's successor, his uncle Shayban ibn Ahmad ibn Tulun, was unable to resist an Abbasid invasion under the command of Muhammad ibn Sulayman al-Katib, with naval support from frontier forces under Damian of Tarsus. This brought an end to his reign and that of the Tulunids.[3]

Culture

Ahmad ibn Tulun founded his own capital, al-Qata'i, north of the previous capital Fustat, where he seated his government. One of the dominant features of this city, and indeed the feature that survives today, was the Mosque of Ibn Tulun. The mosque is built in a Samarran style that was common in the period during which the caliphate had shifted capitals from Baghdad to Samarra. This style of architecture was not just confined to religious buildings, but secular ones also. Surviving houses of the Tulunid period have Samarran-style stucco panels.[7]

Ḵh̲umārawayh's reign exceeded his father's in spending. He built luxuriant palaces and gardens for himself and those he favored. To the Tulunid Egyptians, his "marvelous" blue-eyed palace lion exemplified his prodigality. His stables were so extensive that, according to popular lore, Khumarawaih never rode a horse more than once. Though he squandered the dynastic wealth, he also encouraged a rich cultural life with patronage of scholarship and poetry. His protégé and the teacher of his sons was the famed grammarian Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd Allāh ibn Muḥammad Muslim (d. 944). An encomium was written by Ḳāsim b . Yaḥyā al-Maryamī (d. 929) to celebrate Khumarawaih's triumphs on the battlefield.[8]

Through the mediation of his closest adviser, al-Ḥusayn ibn Ḏj̲aṣṣāṣ al-Ḏj̲awharī, Khumarawaih arranged for one of the great political marriages of medieval Islamic history. He proposed his daughter's marriage to a member of the caliphal family in Baghdad. The marriage between the Tulunid princess Ḳaṭr al-Nadā with the Abbasid caliph al-Mu'tadid took place in 892. The exorbitant marriage included an awesome dowry estimated at between 400,000 and one million dinars. Some speculate that the splendours of the wedding were a calculated attempt by the Abbasids to ruin the Tulunids. The tale of the splendid nuptials of Ḳaṭr al-Nadā lived on in the memory of the Egyptian people well into the Ottoman period, and were recorded in the chronicles and the folk-literature.[8] The marriage's importance arises from its exceptional nature: the phenomenon of marriage between royal families is rare in Islamic history.[9] The concept of dowry given by the bride's family has also been absent in Islamic marriages, where mahr, or bride price has been the custom.[10]

Military

During his reign, Ibn Tulun created a Tulunid army and navy. The need for the establishment of an autonomous armed force became apparent after the revolt of ʿĪsā ibn al-S̲h̲ayk̲h, governor of Palestine, in 870. In response, Ibn Tulun organized an army composed of Sudanese and Greek slave-soldiers. Other reports indicate the soldiers may have been Persians and Sudanese.[4] Ḵh̲umārawayh continued his father's policy of having a multi-ethnic army. His military prowess, in fact, was strengthened by his multi-ethnic regiments of black Sudanese soldiers, Greek mercenaries and fresh Turkic troops from Turkestan.[8]

Ibn Tulun founded an élite guard to surround the Tulunid family. These formed the core of the Tulunid army, around which other larger regiments were built. These troops are said to have been from the region of G̲h̲ūr in Afghanistan, during Ibn Tulun's reign, and from local Arabs during the reign of Ḵh̲umārawayh. In a ceremony held in 871, Ibn Tulun had his forces swear personal allegiance to him. Nevertheless, there were defections from the Tulunid army, most notably of the high-ranking commander Luʾluʾ in 883 to the Abbasids. Throughout its life the army faced such persistent problems of securing allegiance.[4]

Ḵh̲umārawayh also established an elite corps called al-muk̲h̲tāra. The corps was composed of unruly bedouins of the eastern Nile delta. By bestowing privileges upon the tribesmen, and converting them into an efficient and loyal bodyguard, he brought peace to the region between Egypt and Syria. He also re-asserted his control over this strategic region. The regiment also included one thousand Sudanese natives.[8]

A list of military engagements in which the Tulunid army constituted a significant party is as follows:

- In 877, the Tulunid troops, after displaying their strength, forced the Abbasid army under Mūsā ibn Bug̲h̲ā to abandon his plan to depose Ahmad ibn Tulun.[11]

- In 878, the Tulunids, under the pretext of a jihad to defend the frontier districts (Thughur) against the Byzantines, occupied Syria. This campaign was ended prematurely, as Ibn Tulun had to return to Egypt.

- In 885, the Tulunid army led by Khumarawayh met the invading Abbasids at the Battle of the Mills (al-Ṭawāḥīn) in southern Palestine. The Abbasids, led by Aḥmad ibn al-Muwaffaḳ (the future Caliph al-Mu'tadid), had invaded Syria, and the governor of Damascus had defected to the enemy. After both Ahmad and Khumarawayh fled the battlefield, the Ṭūlūnid general Saʿd al-Aysar secured victory.[8]

- From 885–886, the Tulunid forces, led by Khumarawayh, defeated Ibn Kundād̲j, though the latter had superior numbers. A domino effect followed, as the Jazira, Cilicia and regions as far east as Harran submitted to the Tulunid army. Peace treaties with the Tulunids put an end to the military campaigns.[8]

- From 896 to 905, after the emirate's demise the Tulunids were unable to stop the Abbasids from taking their capital al-Qata'i.[8]

Economy

During the reign of Ahmad ibn Tulun, the Egyptian economy remained prosperous. There were propitious levels of agricultural production, stimulated by consistent high flooding of the Nile. Other industries, particularly textiles, also thrived. In his administration, ibn Tulun asserted his autonomy, refusing to pay taxes to the central Abbasid government in Baghdad. He also reformed the administration, aligning himself with the merchant community, and changing the taxation system. Under the Tulunids, there were also repairs in the agricultural infrastructure. The key sector of production, investment, and participation in their Mediterranean-wide commerce, was textiles, linen in particular (Frantz, 281-5).[4] The financial bureaucracy throughout the Tulunid period was headed by members of the al-Madhara'i family.

Financial autonomy

During the period of 870–872, Ibn Tulun asserted more control over Egypt's financial administration. In 871, he took control of the kharaj taxes as well as the thughūr from Syria. He also achieved victory over Ibn al-Mudabbir, the head of the finance office and member of the Abbasid bureaucratic élite.[4]

The de facto ruler of the Abbasid caliphate, al-Muwaffak, took issue with Ibn Tulun's financial activities. He wanted to secure Egyptian revenue for his campaign against the Zanj rebellion (and perhaps limit the autonomy of the Tulunids). This pressing need for funds drew the attention of Baghdad to the considerably more wealthy Egypt.[4] The situation came to a head in 877, when al-Muwaffak, upon not receiving the demanded funds, sent an army to depose Ahmad ibn Tulun.[11] Nevertheless, on at least two occasions, Ibn Tulun remitted considerable sums of revenue, along with gifts, to the central Abbasid administration.[4]

Under Ahmad's son, Khumarawayh, the Abbasids formally entered into a treaty with the Tulunids, thereby ending hostilities and resuming the payment of tribute. Financial provisions were made in the first treaty in 886 with al-Muwaffak. A second treaty with al-Muʿtaḍid, the son of al-Muwaffak, in 892, re-affirmed the political terms of the first. Financially, the Tulunids were to pay 300,000 dīnārs (though this figure may be inaccurate) annually.[8]

Tulunid administration

The Tūlūnid administration over Egypt bore several notable features. The style of rule was highly centralized and "pitiless" in its execution. The administration was also backed by Egypt's commercial, religious and social élite. Ahmad ibn Tulun replaced Iraqi officials with an Egyptian bureaucracy. Overall, the administration relied on the powerful merchant community for both financial and diplomatic support. For example, Maʿmar al-Ḏj̲awharī, a leading member of the merchant community in Egypt, served as Ibn Ṭūlūn's financier.[4]

The Tulunid administration also helped the economy prosper, by maintaining political stability, which in Egypt is a sine qua non. Isolated revolts among the Copts and some Arab nomads in upper Egypt, which never threatened the dynasty's power, were actually a response to the more efficient Tulunid fiscal practices. The economy was strengthened by reforms introduced both immediately before the Tulunids and during their reign. There were changes in the tax assessment and collection system. There was also an expansion in the use of tax-contracts, which were the source of an emergent land-holding élite in this period.[4] Ahmad ibn Tulun's agrarian and administrative reforms encouraged peasants to work their lands with zeal, despite the heavy taxes. He also terminated the exactions of the administration's officers for their personal profit.[11]

One final feature of the administration under Ibn Ṭūlūn was the discontinuation of the practice of draining off the majority of his revenue to the metropolis. Instead, he initiated building programs to benefit other parts of Egypt. He also used those funds to stimulate commerce and industry.[11]

Large expenditures

Ḵh̲umārawayh inherited a stable economy and a wealthy polity from his father. The treasury was worth ten million dīnārs at the young Tulunid's succession. When Ḵh̲umārawayh was killed in 896, the treasury was empty, and the dinar had sunk to one-third its value. Part of this financial disaster is attributed to his addiction to luxury, while squandering wealth to win loyalty was also another cause.[8]

Ḵh̲umārawayh, unlike his father, spent lavishly. For example, he gave his daughter, Ḳaṭr al-Nadā, an extraordinary dowry of 400,000 - 1,000,000 dīnārs, for her wedding in 892 to the Abbasid al-Muʿtaḍid. This move is speculated by some scholars to have been an attempt by the Abbasids to drain the Tulunid treasury.[4]

See also

- List of Sunni Muslim dynasties

Tulunid Amirs

| Titular Name | Personal Name | Reign | |

|---|---|---|---|

| De facto autonomy from the Abbasid Caliphate during the reign of Caliph al-Mu'tamid. | |||

| Amir أمیر |

Ahmad ibn Tulun أحمد بن طولون |

868 - 884 CE | |

| Amir أمیر Abu 'l-Jaysh ابو جیش |

Khumarawayh ibn Ahmad ibn Tulun خمارویہ بن أحمد بن طولون |

884 - 896 CE | |

| Amir أمیر Abu 'l-Ashir ابو العشیر Abu 'l-Asakir ابو العساكر |

Jaysh ibn Khumarawayh جیش ابن خمارویہ بن أحمد بن طولون |

896 CE | |

| Amir أمیر Abu Musa ابو موسی |

Harun ibn Khumarawayh ہارون ابن خمارویہ بن أحمد بن طولون |

896 - 904 CE | |

| Amir أمیر Abu 'l-Manaqib ابو المناقب |

Shayban ibn Ahmad ibn Tulun شائبان بن أحمد بن طولون |

904 - 905 CE | |

| Re-conquered by the Abbasid Caliphate during the reign of Caliph al-Muktafi by general Muhammad ibn Sulayman. | |||

Notes

- Anjum 2007, p. 233.

- Holt, Peter Malcolm (2004). The Crusader States and Their Neighbours, 1098-1291. Pearson Longman. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-582-36931-3.

The two gubernatorial dynasties in Egypt which have already been mentioned, the Tulunids and the Ikhshidids, were both of Mamluk origin.

- "Tulunid Dynasty." Encyclopædia Britannica

- "Ṭūlūnids," Encyclopaedia of Islam

- The first date indicates the year according to the Hijri calendar, while the second one denotes the corresponding Gregorian year

- Lev, Yaacov, War and society in the eastern Mediterranean, 7th-15th centuries, BRILL, 1997, pp.129-130

- Behrens-Abouseif (1989)

- "Ḵh̲umārawayh b. Aḥmad b. Ṭūlūn ," Encyclopaedia of Islam

- Rizk, Yunan Labib.Royal mix Archived 25 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Al-Ahram Weekly. 2–8 March 2006, Issue No. 784.

- Rapoport (2000), p. 27-8

- "Aḥmad b. Ṭūlūn" Encyclopaedia of Islam

References

- Anjum, Tanvir (2007). "The Emergence of Muslim Rule in India: Some Historical Disconnects and Missing Links". Islamic Studies. Islamic Research Institute. 46 (2): 217–240 [p. 233]. JSTOR 20839068.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Behrens-Abouseif, Doris (1989). "Early Islamic Architecture in Cairo". In Islamic Architecture in Cairo: An Introduction. Leiden; New York: E.J. Brill.

- Bianquis, Thierry, Guichard, Pierre et Tillier, Mathieu (ed.), Les débuts du monde musulman (VIIe-Xe siècle). De Muhammad aux dynasties autonomes, Nouvelle Clio, Presses Universitaires de France, Paris, 2012.

- Gordon, M.S. (1960–2005). "Ṭūlūnids". The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition (12 vols.). Leiden: E. J. Brill.

- Haarmann, U. (1960–2005). "Ḵh̲umārawayh b. Aḥmad b. Ṭūlūn". The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition (12 vols.). Leiden: E. J. Brill.

- Hassan, Zaky M. (1960–2005). "Aḥmad b. Ṭūlūn". The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition (12 vols.). Leiden: E. J. Brill.

- "Tulunid dynasty", The New Encyclopædia Britannica (Rev Ed edition). (2005). Encyclopædia Britannica, Incorporated. ISBN 978-1-59339-236-9

- Rapoport, Yossef. "Matrimonial Gifts in Early Islamic Egypt," Islamic Law and Society, 7 (1): 1-36, 2000.

- Tillier, Mathieu (présenté, traduit et annoté par). Vies des cadis de Miṣr (257/851-366/976). Extrait du Rafʿ al-iṣr ʿan quḍāt Miṣr d’Ibn Ḥağar al-ʿAsqalānī, Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale (Cahier des Annales Islamologiques, 24), Cairo, 2002. ISBN 2-7247-0327-8

- Tillier, Mathieu. « The Qāḍīs of Fusṭāṭ–Miṣr under the Ṭūlūnids and the Ikhshīdids: the Judiciary and Egyptian Autonomy », Journal of the American Oriental Society, 131 (2011), 207–222. Online: https://web.archive.org/web/20111219040853/http://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/IFPO/halshs-00641964/fr/