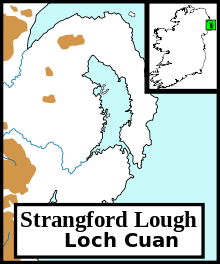

Strangford Lough

Strangford Lough (from Old Norse Strangr Fjörðr, meaning "strong sea-inlet"[1]) is a large sea loch or inlet in County Down, in the east of Northern Ireland. It is the largest inlet in the British Isles, covering 150 km2 (58 sq mi). The lough is almost totally enclosed by the Ards Peninsula and is linked to the Irish Sea by a long narrow channel at its southeastern edge. The main body of the lough has at least seventy islands along with many islets (pladdies), bays, coves, headlands and mudflats. Strangford Lough was designated as Northern Ireland's first Marine Conservation Zone (MCZ) under the introduction of the Marine Act (Northern Ireland) 2013. It has also been designated a Special Area of Conservation under the EU Habitats Directive, and its abundant wildlife is recognised internationally for its importance.

In the medieval and early modern period Strangford Lough was known in Irish as Loch Cuan, meaning "sea-inlet of bays/havens".[1]

Strangford Lough is a popular tourist destination noted for its fishing and scenery. Towns and villages around the lough include Killyleagh, Comber, Newtownards, Portaferry and Strangford. The latter two straddle either shore of the narrow channel connecting the lough to the Irish Sea, and are connected by a car ferry.

Name

The name Strangford comes from Old Norse Strangr-fjörðr, meaning 'strong sea-inlet'.[2] The Vikings were active in the area during the Middle Ages. Originally, this name referred only to the narrow channel linking the lough to the sea (between the villages of Strangford and Portaferry).[2] Up until about the 18th century, the main body of the lough was better known by the (older) Irish name Loch Cuan, meaning "loch of the bays/havens".[2] This name was anglicized as Lough Coan, Lough Cone, Lough Coyn, Lough Coin, or similar.[2]

The narrow channel may have been known in Latin as the fretum Brene.[3] In Ulster-Scots the lough's name is spelt Strangfurd or Strangfirt Loch.[4][5]

Ptolemy's Geography (2nd century AD) described a point called Ουινδεριος (Winderios, "pleasant river") which may have referred to Strangford Lough.[6]

Geology

The loch was formed at the end of the last ice age and is generally under 10m deep, but can reach 50-60m in parts, generally the centre channel.[7]

Flora

Flowering plants

Common cord-grass (Spartina anglica) C.E. Hubbard was introduced in the mid-1940s is now abundant.[8]

Algae

Maerl is a calcareous deposit, in the main, of two species, of calcareous algae Phymatolithon calcareum and Lithothamnion glaciale which form free-living beds of unattached, branched corallines, living or dead, in Strangford Lough.[9]

The rocky and boulder shores toward the south of the lough are dominated by the seaweed knotted wrack Ascophyllum nodosum. The usual zonation of weeds on these shore is, at the top channel wrack (Pelvetia canaliculata (L.) Dcne. et Rhur.), followed by spiral wrack (Fucus spiralis L.), then knotted wrack (Ascophyllum nodosum (L.) Le Jol) with some admixture of bladder wrack (Fucus vesiculosus) L. and then serrated wrack (Fucus serratus L.) before coming to the low water kelps.[10]

A brown seaweed named Sargassum muticum, originally from the Pacific (Japan) was discovered on 15 March 1995 in Strangford Lough at Paddy's Point. The plants were well established on mesh bags containing oysters. The bags had been put out in 1987 containing Pacific oysters (Crassostrea gigas) imported from Guernsey. This Sargassum is known to be a highly invasive species.[11][12]

Other algae include:[13]

- Apoglossum rusciofolium (Turn.) J. Ag.

- Spyridia filamentosa (Wulf.) Harv.

- Sphondylothamnion multifium (Huds.) Näg.

- Griffithsia corallinoides (L.) Batt.

- Compsothamnion gracillimum de Toni

- Compsothamnion thuyoides (Sm.) Schmitz

- Calliothamnion corymbosum (Sm.) Lyngb

- Rhodymenia delicatula P.Dang.

- Haemescharia hennedyi (Harv.) Vinogradova

- Rhodophyllis divaricate (Stackh.) Papenf.

- Calliblepharis jubata (Good. et Woodw.) Kütz.

- Calliblepharis ciliata (Huds.) Kütz

- Peyssonnelia dubyi P. et H. Crouan

- Plagiospora gracilis Kuck

- Gloiosiphonia capillaris (Huds.) Carm.

- Dudresnaya verticillata (With.) Le Jol.

- Scinaia pseudocrispa (Clem.)

- Cremades/S. turgida Chemin

- Porphyropsis coccinea (J.Ag. ex Aresch) Rosenv.

- Pelvetia canaliculata (L.) Dcne. et Thur.

- Fucus vesiculosus var. volubilis Turn.

- Fucus cottonii Wynne et Magne

- Colpomenia peregrine (Sauv.) Hame

- Asperococcus compressus Griff. ex Hook.

- Striaria attenuate (Grev.) Grev.

- Myriotrichia clavaeformis Harv.

- Tilopteris mertensii (Turn.) Kütz.

- Chordaria flagelliformis (O.F.Müll.) C.Ag.

- Spermatochnus paradoxus (Roth) Kütz.

- Pseudolithoderma extensum (P. et H. Crouan) Lund.

- Enteromorpha ralfsii Harv.

- Chlorochytrium sp.

Fauna

Strangford Lough and Islands is an Important Bird Area.[14] Strangford Lough is an important winter migration destination for many wading and sea birds. Animals commonly found in the lough include common seals, basking sharks and brent geese. Three quarters of the world population of pale bellied brent geese spend winter in the lough area.[15] Often the numbers are up to 15,000.[16]

The invasive carpet sea squirt, Didemnum vexillum, was found in the Lough in 2012.[17]

Tidal electricity

In 2007 Strangford Lough became home to the world's first commercial tidal stream power station, SeaGen. The 1.2 megawatt underwater tidal electricity generator, part of Northern Ireland's Environment and Renewable Energy Fund scheme, took advantage of the fast tidal flow in the lough which can be up to 4 m/s. Although the generator was powerful enough to power up to a thousand homes, the turbine had a minimal environmental impact, as it was almost entirely submerged, and the rotors turned slowly enough that they pose no danger to wildlife.[18][19][20]

In 2008 a tidal energy device called Evopod was tested in Strangford Lough near the Portaferry Ferry landing.[21] The device was a 1/10 scale prototype, monitored by Queen's University Belfast. The device was a semi-submerged floating tidal turbine, moored to the seabed via a buoy-mounted swivel. The scale device was not grid connected.

Sports

In July 2016 the Strangford Lough and Lecale Partnership, Scottish Coastal Rowing Association, Newry, Mourne and Down District Council and Ards and North Down Borough Council, together with local rowing clubs based on Strangford Lough and the Ards Peninsula hosted the world community, coastal rowing championships “Skiffie Worlds 2016”. The event was attended by 50 clubs from Scotland, England, Northern Ireland, the Netherlands, The United States, Canada and Tasmania. Racing was held over a 2 km course on Strangford Lough at Delamont Country Park.[22]

Ferry

The Portaferry–Strangford ferry service has linked Portaferry and Strangford, at the mouth of the Lough, without a break and for almost four centuries.[23] The alternative road journey is 47 miles (76 km) and takes about an hour and a half, while the ferry crosses the 0.6-nautical-mile (0.69 mi; 1.1 km) strait in 8 minutes.[24] The subsidised public service carries both passengers and vehicles, and operates at a loss of more than £1m per year but is viewed as an important transport link to the Ards Peninsula.[25]

Archaeology

Strangford Lough has a substantial archaeological heritage. Intertidal archaeological surveys in recent years have brought hundreds of sites to light, including fish traps, tidal mills, kelp walls and harbours and landing places.[26]

See also

- List of loughs in Ireland

- Nendrum Monastery

References

- PlaceNames NI - Strangford Lough

- "Place Names NI - Home". www.placenamesni.org. Retrieved 26 April 2018.

- II-Landing Places of St. Patrick, "Saint Patrick: his life and mission", Mrs. THOMAS qONCANNON, The Talbot Press Ltd., Dublin & Cork, From The James D. Phelan Celtic Collection

- Jordan's Castle (Ulster-Scots translation) Department of the Environment.

- Nendrum (Ulster-Scots translation) Archived 2011-08-30 at the Wayback Machine Department of the Environment.

- http://www.romaneranames.uk/essays/ireland.pdf

- "The Natural History of Strangford Lough". culturenorthernireland.org. Retrieved 14 September 2018.

- Hackney, P. (Ed) 1992. Stewart & Corry's Flora of the North-east of Ireland. Third Edition. Institute of Irish Studies, The Queen's University of Belfast. ISBN 0 85389 446 9 (HB)

- Blake,C. and Maggs, C.A. 2001. A study of maerl beds in Strangford Lough, including determination of growth rates. in Nunn, J.D. (ed). Marine Biodiversity in Ireland and Adjacent Waters. Ulster Museum, Belfast. MAGNI publication no. 008

- Brown, R. 1990. Strangford Lough. The Wildlife of an Irish Sea Lough. The Institute of Irish Studies, The Queen's University of Belfast

- Boaden, P.J.S. 1995. The adventive seaweed Sargassum muticum (Yendo) Fensholt in Strangford Lough, Northern Ireland. Ir.Nat. J. 25:111 - 113

- Davison,D.M. 1999. Sargassum muticum in Strangford Lough, 1995 - 1998; a review of the introduction and colonisation of Strangford Lough MNR and cSAC by the invasive brown algae Sargassum muticum. Environment and Heritage Service Research and Development Series. No. 99/27.

- Morton, O. 1994. Marine Algae of Northern Ireland. Ulster Museum, Belfast. ISBN 0-900761-28-8

- BirdLife International (2016) Important Bird and Biodiversity Area factsheet: Strangford Lough and islands. Downloaded from http://www.birdlife.org on 17/08/2016

- "Hands on Nature - Strangford". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 26 April 2018.

- Gallagher, L. and Rogers, D. 1986 Castle, Coast and Cottage The National Trust in Northern Ireland. The Blackstaff ISBN 0-85640-497-7

- "Carpet sea squirt found in Lough". google.com. Retrieved 26 April 2018.

- "The Times & The Sunday Times". thetimes.co.uk. Retrieved 26 April 2018.

- "Top News". www.renewableenergyworld.com. Retrieved 26 April 2018.

- "Tidal energy system on full power". BBC News. 18 December 2008. Retrieved 13 September 2009.

- "First Testing of Evopod at Strangford Narrows". Ocean Flow Energy Ltd. 12 June 2008. Retrieved 15 August 2015.

- Nolan, Caroline. "Skiffie Worlds 2016". www.strangfordlough.org. Retrieved 26 April 2018.

- "Strangford Lough Ferry - History". Northern Ireland Roads Department. Archived from the original on 18 September 2009. Retrieved 13 September 2009.

- "About the Ferry". Northern Ireland Roads Department. Archived from the original on 7 December 2009. Retrieved 13 September 2009.

- "Strangford Ferry Operating at a loss". Portaferry Online. Archived from the original on 1 November 2013. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- O'Sullivan, Aidan & Breen, Colin (2007). Maritime Ireland. An Archaeology of Coastal Communities. Stroud: Tempus. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-7524-2509-2.

Further reading

- Boaden, P.J.S., O'Connor, R.J. and Seed, R. 1975. The composition and zonation of a Fucus serratus community in Strangford Lough, Co. Down. J. exp. Biol. Ecol. 17: 111 - 136.

- Walsh, B. 2009. Catching the Currents. Time 173 no.4. p. 44.

- Deane, C.Douglas. 1971. Mammals of Strangford Lough. In Anon (Editor) Strangford Lough. 22 - 23. National Trust. Belfast.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Strangford Lough. |