LGBTQ migration

LGBT migration is the movement of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBT) people around the world and domestically, often to escape discrimination or ill treatment due to their sexuality. Globally, many LGBT people attempt to leave discriminatory regions in search of more tolerant ones.

| Part of a series on |

| LGBT topics |

|---|

| lesbian ∙ gay ∙ bisexual ∙ transgender |

|

Issues

|

|

Academic fields and discourse |

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| LGBT rights |

|---|

|

| lesbian ∙ gay ∙ bisexual ∙ transgender |

|

Overview

|

|

Organizations

|

|

|

LGBT discrimination and tolerance by region

Australia

In the early 1900s, homosexuality was also used as a valid reason for deportation in Australia.[1] The nation specifically allowed for homosexual immigration in the 1980s.[2]

North America

In the beginning of the 20th century, homosexuality was considered a mental illness and used to bar homosexuals from immigrating into the United States, and Canada.[1] Canada allowed for homosexual immigration in 1991.[2]

The United States

In the United States, the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 became the first policy to explicitly prevent “sexual deviates” from entering the country, and it also required the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) to deport these individuals.[3]

The Lavender Scare of the anti-communist 1950’s America created additional persecution of homosexuals and a spirit of fear among people with same-sex attraction. After the war, a "Pervert Elimination Campaign" was initiated in Washington D.C. by the U.S. Park Police. D.C. parks witnessed a number of sex charge arrests of gay men, many of whom subsequently lost their jobs.[4]

The United States military excluded homosexuals until 2011, and proposed that they were unfit for service. The law commonly known as “Don’t ask, don’t tell” allowed LGB people to serve as long as they kept their sexuality hidden. The Obama administration allowed LGB people to serve openly in the military.[5]

Obstacles for LGBT asylum-seekers and refugees

In the United States, judges and immigration officials require that homosexuality must be socially visible in order for sexual persecution to be a viable complaint. Additionally, homosexuality must be a permanent and inherent characteristic to be considered by U.S. immigration officials.[6]

Currently, the US Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) will consider LGBT refugee and asylum claims in their immigration courts, but as a result of cumberstone legal processes, LGBT individuals who are applying for asylum often have a difficult time representing themselves properly in court. [7]

Mexico

In Mexico, between 2002 and 2007 roughly 1000 people—mostly gay men—were recorded as murdered for homosexual acts. That statistic makes Mexico the country with the second-highest rate of homophobic crimes in the world (after Brazil).[8][9] Only 16 women were established to have been murdered because of homosexuality between 1995 and 2004.[10]

A UAM study found that the most frequent types of discrimination were "not hiring for a job," "threats of extortion and detention by police," and "abuse of employees."[11]

Europe

Greeks, Romans, and most Mediterranean cultures glorified homosexuality in ancient times, and prior to the 7th century Europe had no secular laws against it.[12]

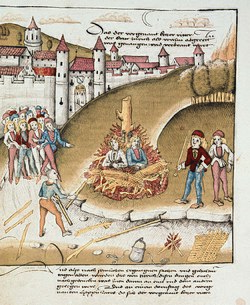

Beginning in the 16th and 17th centuries, Europe considered all homosexuality equivalent to the biblical sin of sodomy, punishable by death.[13]

The Buggery Act of 1533 and the Laws in Wales Act of 1542, punished gay sex with death by hanging in England and Wales.[13]

Under the rule of Joseph Stalin, Russia outlawed male homosexuality in 1933 and made the offense punishable by 5 years of hard labor in prison. This was not repealed until 1993.[14][15]

More than half of the 80 countries that continue to outlaw homosexuality were once British colonies.[16] It is theorized that, during 19th century colonial rule, many of the British anti-gay policies that were enacted still retain influence in these former colonies.[17]

Africa

Some African countries punish homosexuality with the death sentence, like Mauritania, Sudan, and northern Nigeria, where lesbians and gays are sometimes stoned to death. Institutional sexual persecution is also rampant in Cameroon, Burundi, Uganda, and Gambia. Zimbabwe banned homosexual acts in 1995.[18][19][20]

Uganda

In Uganda “touching a person with homosexual intent” results in a life sentence in prison, and actions that are perceived to promote homosexuality carry a seven-year sentence – these actions include advocating for gay human rights, belonging to a gay organization, and advocating for safe homosexual sex.[20][21]

South Africa

Corrective rape, the rape of LGBT people in order to “correct” their “pathologies”, is a well-known phenomenon in South Africa.[22] This can be especially harmful, considering the high instance of HIV/AIDS in South Africa.[23]

Nigeria

There is no legal protection against discrimination in Nigeria—a largely conservative country of more than 170 million people, split between a mainly Muslim north and a largely Christian south. Very few LGBT persons are open about their orientation, and violence against LGBT people is frequent.

Edafe Okporo, a well known LGBT activist, suffered stigma and discrimination based on his sexual orientation. Fearing for his life, he fled to the United States seeking asylum.[24]

Asia

China

Bisexual behavior was considered normal behavior in Ancient China.[25]

Following interactions with the West, China began to view homosexuality as a mental illness in the late Qing Dynasty.[26] It was outlawed in 1740.[27] Later, in the Republic of China, homosexuality was not illegal but it was vigorously policed as such.[28]

Afghanistan

Under the influence of the Taliban, men accused of sodomy were sometimes killed by having a wall toppled over them. In February 1998, three men accused of sodomy were taken to the base of a mud and brick wall, which was then toppled over onto them by a tank. A similar death sentence for two men occurred in March 1998. Taliban leader, Mullah Mohammed Hassan, was reported to say, "Our religious scholars are not agreed on the right kind of punishment for homosexuality. Some say we should take these sinners to a high roof and throw them down, while others say we should dig a hole beside a wall, bury them, then push the wall down on top of them."[29] Prior to Taliban rule, the supposedly "Islamic" punishment of having walls toppled onto homosexuals was not precedented.[30]

After the fall of the Taliban, homosexuality became punishable by fines and prison sentences.[30]

Iran

In Iran a voluntary militia, the Basij, functions partially as a "morality police." Among other things, the Basij has been known to find and persecute LGBT people.[31]

Iraq

In Baghdad in 2009 a characteristic assortment of anti-gay crimes were committed. The Iraqi militia began torturing male homosexuals in ways that usually resulted in death. The Iraqi LGBT group suffered 63 cases of torture within its members. Murders of LGBT people were called for by anonymous individuals.[32]

Israel

Israel allows lesbians and gays in their military, which first occurred in 1993. Additionally, discrimination against lesbians and gays is specifically prohibited.[33][34] The Israeli government also gives funding to LGBT organizations and the prime minister has publicly condemned LGBT hate crimes.[35] LBGT immigrants who were legally married in other countries are legally recognized in Israel.[35]

North Korea

The North Korean government proposes that gay culture is caused by the vices of capitalist societies.[36] Homosexuality can be punished by up to 2 years in prison.[37]

Saudi Arabia

In Saudi Arabia, homosexuality carries a maximum punishment of public execution when the activity is deemed to engage in LGBT social movements, but other punishments include forced sex changes, fines, imprisonments, and whipping.[38]

United Arab Emirates

In 2006, 11 gay men at a private party were given 5 years in prison each for admitting to be gay and organizing a cross-dressing party.[39] The two main youthful crimes from ages 14–18 within the population of Arab youth that are located in the Gulf States are petty theft and homosexual acts. In these countries, youth over the age of 16 are tried as adults, so these homosexual actions may cause severe and dire punishment within the legal system.[40]

Internationally

In September 2013, countries of the U.N. declared to protect LGBT rights, counter global homophobia, and support educational campaigns for the advancement of LGBT rights.[41]

In 1991 The World Health Organization (WHO) declassified homosexuality as a mental illness.[42]

Current trends of migration

Prominent countries known for substantial LGBT emigration include Iran, Iraq, Jamaica, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Mexico, and Brazil.[43][44][45]

LGBTQ immigrants are seen frequently to immigrate to Canada, Britain, and the United States.[45] In 1994, U.S. immigration law recognized sexual persecution as grounds for seeking asylum. U.S. President Barack Obama ordered federal agencies to provide asylum for persecuted LBGTQ persons.[46] As of 2008, only Norway, Iceland, Denmark, the United States, and Switzerland have enacted immigration equality allowing for partner sponsorship.[47]

The number of LGBT people seeking asylum into the United States is not currently known.

_-_PRIDE_PARADE_IN_JERUSALEM.jpg)

Middle Eastern LGBT migration to Israel

Compared to its Middle Eastern neighbors, Israel has more LGBT-supportive policies for Israeli citizens, and it accepts LGBT asylum applicants. Israel ratified the UN Convention and Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees in 1951, which theoretically gives protection or asylum to anyone with a "well-founded fear of being persecuted" and forbids the deportation of refugees to the country where their lives were initially threatened. This policy has not been explicitly followed by Israel, but Palestinian LGBT immigrants have been accepted into Israeli LGBT communities, where previous legal LGBT marriages are officially recognized, though gay marriage is not legal in Israel.[48] As a result, Middle Eastern migration of LGBT people to Israel has been seen. Tel Aviv was dubbed the “gay capital of the Middle East” by Out Magazine in 2010.[49]

However, critics point out that the state of Israel has used the issue of gay rights as a way to distract attention from other human rights abuses perpetrated by the state (a practice called Pinkwashing) and revitalize the nation's image in the international community.[50][51][52] These critics suggest that, in actuality, Tel Aviv and Israel at large are strongly divorced from the experiences and goals of queer communities across the rest of the MENA region.[52] Thus, Israel's LGBTQ migrants and asylum-seekers from neighboring Arab countries cannot necessarily be considered to moving to a host nation with close cultural affinity and ease of acclimation.

Nepal and the Philippines

Most families of LGBT emigrants from Nepal and the Philippines indicate that, although most emigrants' families do not approve of their lifestyles, remittance payments (i.e. when the person who left the country sends money back to their family) are a proven aid to breaking down the controversies surrounding their gender and/or sexual nonconformity.[53]

Irish LGBT migration to London

As of 2009, Irish people have been known to migrate to Britain and especially to London where they typically try to find employment. More recently, London has seen an immigration of Irish LGBT people who are hoping to find a more accepting social environment. Urban areas and large international cities are often seen as tolerant and sexually diverse, and many already contain established queer communities.[54]

Irish LGBT immigrants often experience vulnerability in the absence of family networks, which is exacerbated in the context of homophobia and sexual discrimination. Legal protection against sexual discrimination in employment was only introduced in the UK in 2003. Even when legislative provisions and support are in place, homophobia continues to make life and the process of migration difficult for queer migrants.[54]

Asylum seekers and immigrants

Refugees, defined by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), are displaced persons who “owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality, and is unable to, or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country.”[55] LGBT refugees are those who are persecuted due to their sexuality or gender orientation and are unable to find protection from their home nation. Individuals can seek refugee status or asylum in several different ways: they can register at an U.N. outpost, visit their intended country and a visa and apply once they are in the country, or they can make a report at their official government representation headquarters.[55] Once a claim is filed, the intended country for reallocation evaluates eligibility of asylum requirements.[UNHCR] During meetings to determine eligibility and suitability, applicants face obstacles that can prevent them from making a successful claim.[56][55][57]

Navigating the system

The first obstacle asylum seekers face is navigating the process in applying for refugee status or asylum. Countries like the United States, do not offer any legal assistance in making the asylum claim, requiring the applicant to find and fund their own legal representation.[56] Many applicants inside the United States do not get a lawyer during this process and represent themselves. Other countries, such as the United Kingdom offer legal aid, increasing the number of applicants who have access to legal advice and representation in applying for refugee status or asylum.[56]

While many refugees share the same difficulties navigating the system, LGBT refugees face additional challenges due to the nature of their claim. Communities are built among LGBT refugees and asylum-seekers, leading to a network of advice about how to navigate the system.[56][55] These networks help share success stories in navigating the system.[55] Agencies funded by the government to resettle and assist refugees and asylum-seekers can offer further, more general assistance. According to Carol Bohmer and Amy Shuman, statistics make it clear that chances of a successful asylum or refugee claim are greatly improved with legal assistance in the United States.[56][58] Furthermore, the percentage of refugee claims admitted for LGBT claims tend to be lower compared to its heterosexual counterparts.

Refugees also face difficulty in securing housing once their application process is approved. In the United Kingdom, for instance, refugees can face difficulties integrating into neighborhoods, and are faced with gaps in provision, choices of housing options, and on-going support.[59]

Credibility

Due to the nature of sexuality and gender claims, applicants often encounter issues with the credibility of their stories.[60][61][55] Sexuality and gender identification is a private expression that cannot be determined by appearance.[62] In seeking asylum, applicants are expected to prove their sexual or gender orientation as a proof of being a part of a particular social membership. They are also expected to prove that they are in fear of their life.[61][56] Applicants applying for asylum due to sexual orientation are asked to present an “identity narrative.[63][61][55] There are several different credibility obstacles that applicants face during the application process.

According to Neva Wagner, asylum claims in the United Kingdom face a “notorious challenge.” Over 98% of sexual orientation claims were denied in the United Kingdom between 2005 and 2009, compared to the 76.5% refusal rating for all asylum applicants. Bisexual claimants face an even greater challenge due to their dual sexuality. In bisexuality claims, claimants must demonstrate that they are at risk for persecution, even if their sexuality allows them to act in a heterosexual manner.

Lawyer S Chelvan reported to the Huffington post reported that the use of pornographic evidence—individuals taping themselves having sex with same sex partners—has risen due to challenges to credibility of queer claims. Furthermore, immigration officials have refused witnesses for the credibility of queer asylum claims if the witness did not have sex with applicant. Credibility becomes an issue, as many refugees keep their identity as being queer a secret from their own family and friends in order to avoid persecution.[57][64]

Cultural differences in gender and narratives

The first step in verifying eligibility for asylum-seekers and refugee applicants is the initial investigation into why asylum is being sought. This is often done through applicant narratives, where the applicant is asked questions about their experiences and are evaluated in how their stories match the eligibility requirements.[61][55] In the U.K., initial credibility determinations are given great significance. Initial determinations are not reviewable by appeal, and if credibility is examined, initial determinations are given precedence.[63] Retelling their experiences can be traumatic and unaligned with a chronological telling that is expected in Westernized narratives.[61] There is also an inherent gendered expectation in narratives. Rachel Lewis writes that “The racialized, classed, and gendered stereotypes of male homosexual identity typically invoked by asylum adjudicators pose particular challenges to lesbian asylum applicants.”[60]

Women face additional obstacles, whether they are lesbians, bisexuals, transsexuals, or heterosexual. Women's narratives of persecution often take place in the home, so the violence experienced by females is often taken less seriously than males.[65] Rachel Lewis argues that same-sex female desires and attraction are often overlooked in the U.K. cases, and applicants face a "lack of representational space within heteronormative asylum narratives for the articulation of same-sex desire."[64] Simply put, lesbian narratives don't fit into the expected picture of an LGBT applicant. Instead, the expectations is for women to be discreet in their affairs to avoid persecution.[64] Persecution of lesbians can be seen as routine in countries where it is common for women to be raped—every women then, is at risk of being attacked, and their lesbian identity would not constitute being persecuted for being a part of a social grouping.[66] Women who appear vulnerable because they are openly lesbian or foreign women "in need of rescue from oppressive patriarchal--read third world--cultures" are more likely to be granted political asylum due to sexuality than women who identify as lesbian privately.

References

- Bashford, A. Howard (2004). "Immigration and Health: Law and Regulation in Australia, 1901-1958". Health & History. 6 (1): 97–112. doi:10.2307/40111469. JSTOR 40111469.

- "Applying for Asylum". Immigration Equality.

- Pickert, Jeremiah. "Immigration for Queer Couples: A Comparative Analysis Explaining the United States’ Restrictive Approach ." A Worldwide Student Journal of Politics. "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 23, 2013. Retrieved October 22, 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) (accessed October 20, 2013).

- Johnson, David K. The Lavender Scare: The Cold War Persecution of Gays and Lesbians in the Federal Government. 2004.

- "Don't Ask, Don't Tell - United States policy". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- Gay Lesbian Equality Network. 2011. “Immigration Provisions in Ireland.”

- Alvarez-Hernandez, Luis. "Whose Land of the Free? Latina Transgender Immigrants in the United States" (PDF). Indian Journal of Health, Sexuality, & Culture. 5: 135–147.

- AFP (10 May 2007). "En cinco años han sido asesinadas 1.000 personas por homofobia en México" (in Spanish). Enkidu.

- EFE (19 May 2006). "ONGs denuncian que México es el segundo país con más crímenes por homofobia" (in Spanish). Enkidu.

- EFE (15 May 2007). "El 94 por ciento de los gays y lesbianas se sienten discriminados en México" (in Spanish). Enkidu. Retrieved 16 December 2007.

- Notimex (13 June 2007). "La población homosexual sufre violencia y exclusión en México según una investigación de la UAM" (in Spanish). Enkidu. Retrieved 15 December 2007.

- Evans, Len. "Gay Chronicles from the Beginning of Time to the End of World War II." WebCite. (accessed September 30, 2013).

- "Timeline of UK LGBT History - LGBT History UK." UK LGBT History Project Wiki. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on February 14, 2013. Retrieved May 11, 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) (accessed September 30, 2013).

- Russia: Update to RUS13194 of 16 February 1993 on the treatment of homosexuals.

- "Anne Buetikofer -- Homosexuality in the Soviet Union and in today's Russia".

- ILGA: 2009 Report on State Sponsored Homophobia (2009).

- Hepple, Joshua. "Will Sexual Minorities Ever Be Equal? The Repercussions of British Colonial "Sodomy" Laws." Equal Rights Review. (2012): 52. (accessed October 23, 2013).

- "Confronting homophobia in South Africa", University of Cambridge, 27 September 2011]

- Epprecht, Marc (2004). Hungochani: the history of a dissident sexuality in southern Africa. Montreal. p. 180.

- Human Rights First, "Uganda." Accessed October 23, 2013. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on October 1, 2013. Retrieved October 24, 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Wasswa, Henry. Aljazeera, "Uganda's 'Kill the Gays' bill spreads fear." Last modified January 3, 2013. Accessed October 23, 2013.

- Bartle, E. E. (2000). "Lesbians And Hate Crimes". Journal of Poverty (pdf).></Bartle, E. E. (2000). "Lesbians And Hate Crimes". Journal of Poverty (pdf).

- Mieses, Alexa. GMHC Treatment Issues, "Gender inequality and corrective rape of women who have sex with women." Last modified December 2009. Accessed October 23, 2013.

- "Pulse".

- Crompton, Louis, Homosexuality and Civilization, Harvard University, 2003.

- Kang, Wenqing. Obsession: male same-sex relations in China, 1900-1950, Hong Kong University Press. Page 3.

- Francoeur, Robert T.; Noonan, Raymond J. (2004). The Continuum complete international encyclopedia of sexuality. The Continuum International Publishing Group, Inc.

- "History of Chinese homosexuality". Shanghai Star. 2004-04-01. Retrieved July 3, 2009.

- "Pakistan wipes out half of Quetta Shura". The News International. Archived from the original on 2010-03-04. "According to well-informed diplomatic circles in Islamabad, the decision-makers in the powerful Pakistani establishment seem to have concluded in view of the ever-growing nexus between the Pakistani and the Afghan Taliban that they are now one and the same and the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) and the Quetta Shura Taliban (QST) could no more be treated as two separate Jihadi entities."

- Rashid, Ahmed (12 May 2019). Taliban: Islam, Oil and the New Great Game in Central Asia. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 9781860648304 – via Google Books.

- Iran's Basij Force -- The Mainstay Of Domestic Security, By Hossein Aryan, RFERL, December 07, 2008.

- "Iraq: Torture, Cruel, Inhuman and Degrading Treatment of LGBT People". 20 April 2009.

- Greenberg, Joel (2002-10-16). "Tel Aviv Journal; Once Taboo, a Gay Israeli Treads the Halls of Power". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-05-07.

- Belkin, Aaron; Levitt, Melissa (2001). "Homosexuality and the Israel Defense Forces: Did Lifting the Gay Ban Undermine Military Performance?". Armed Forces & Society. 27 (4): 541–566. doi:10.1177/0095327x0102700403. PMID 17514841.

- Segal, Mark. The Bilerico Project, "Israel, LGBT People & Equality Forum." Last modified March 28, 2012. Accessed November 5, 2013.

- Global Gayz. "Gay North Korea News & Reports 2005". Archived from the original on 2005-10-18.. Retrieved on May 5, 2006.

- Spartacus International Gay Guide, page 1217. Bruno Gmunder Verlag, 2007.

- Whitaker, Brian (18 March 2005). "Arrests at Saudi ’gay wedding’".The Observer (London). "Saudi executions are not systematically reported, and

- Ireland, Doug. Direland, "26 Men Imprisoned 5 Years Each for Being Gay in United Arab Emirates." Last modified February 11, 2006. Accessed October 23, 2013.

- Booth, Marilyn. "Enduring Ideals and Pressures to Change." The world's youth: Adolescence in eight regions of the globe (2002): 207.

- "At UN meeting, countries commit to protect gay rights, combat discrimination". UN News. 26 September 2013.

- "World Health Organization, "The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders ." Accessed October 23, 2013" (PDF).

- Foundation, Thomson Reuters. "Asylum system humiliates gay refugees". news.trust.org.

- Dan, Bilefsky. "Gays Seeking Asylum in U.S. Encounter a New Hurdle." NY Times, January 28, 2011.

- Mayton, Joseph. LGBT Rights, "Gay, Muslim, and Seeking Asylum." Last modified June 18, 2013. Accessed October 20, 2013.

- U.S. News & World Report: Obama Offers Asylum to Overseas Gays. December 6, 2011.

- Wilets, James. 2008. “Immigration: To Admit or Deny? A Comparative Perspective on Immigration Law for Same-Sex Couples: How the United States Compares to Other Industrialized Democracies.” Nova Law Review 32:327-356.

- "Israel's Treatment of Gay Palestinian Asylum Seekers The Washington Note by Steve Clemons". 6 June 2011.

- Schaefer, Brian (23 March 2013). "The White City at the End of the Rainbow". Haaretz.

- Kaufman, David (May 13, 2011). "Is Israel Using Gay Rights to Excuse Its Policy on Palestine?". Time Magazine. Retrieved July 5, 2020.

- Schulman, Sarah (2011-11-22). "Opinion | Israel and 'Pinkwashing'". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-07-04.

- ""To celebrate Pride, you need to know about pinkwashing" (infographic series)". Instagram, @babyfistcollective. June 29, 2020.

|first=missing|last=(help) - Wood, Stephen (May 2016). "Migration, Mobility and Marginalisation: Consequences for Sexual and Gender Minorities". IDS Policy Briefing (118). Retrieved December 1, 2016.

- Ryan-Flood, Roisin (2009). Sexuality, Citizenship and Migration: the Irish Queer Diaspora in London: Full Research Report ESRC End of Award Report, RES-000-22-2612. Swindon: ESRC

- 1962-, Murray, David A. B. (2015). Real queer? : sexual orientation and gender identity refugees in the Canadian refugee apparatus. London. ISBN 9781783484409. OCLC 935326236.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Carol., Bohmer (2008). Rejecting refugees : political asylum in the 21st century. Shuman, Amy, 1951-. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0415773768. OCLC 123912524.

- Shuman, Amy; Bohmer, Carol (2014-10-31). "Gender and cultural silences in the political asylum process". Sexualities. 17 (8): 939–957. doi:10.1177/1363460714552262.

- SCHOENHOLTZ, ANDREW; JACOBS, JONATHON. "The State of Asylum Representation: Ideas for Change". Georgetown Immigration Law Journal.

- Phillips, Deborah (2006-07-01). "Moving Towards Integration: The Housing of Asylum Seekers and Refugees in Britain". Housing Studies. 21 (4): 539–553. doi:10.1080/02673030600709074. ISSN 0267-3037.

- Lewis, Rachel A (2014-10-31). ""Gay? Prove it": The politics of queer anti-deportation activism". Sexualities. 17 (8): 958–975. doi:10.1177/1363460714552253.

- Forbear, Katherine (2015). ""I Thought We Had No Rights" - Challenges in Listening, Storytelling, and Representation of LGBT Refugees". Studies in Social Justice. 9.

- Vogler, Stefan (2016). "Legally Queer: The Construction of Sexuality in LGBQ Asylum Claims". Law & Society Review. 50 (4): 856–889. doi:10.1111/lasr.12239.

- Wagner, Neva (Winter 2016). "B is for Bisexual: The Forgotten Letter in U.K. Sexual Orientation Asylum Reform". Transnational Law & Contemporary Problems. 26.

- Shuman, Amy; Hesford, Wendy S (2014-10-31). "Getting Out: Political asylum, sexual minorities, and privileged visibility". Sexualities. 17 (8): 1016–1034. doi:10.1177/1363460714557600.

- Berger, Susan A. (2009-03-01). "Production and Reproduction of Gender and Sexuality in Legal Discourses of Asylum in the United States". Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society. 34 (3): 659–685. doi:10.1086/593380. ISSN 0097-9740.

- Lewis, Rachel (2013-09-05). "Deportable Subjects: Lesbians and Political Asylum". Feminist Formations. 25 (2): 174–194. doi:10.1353/ff.2013.0027. ISSN 2151-7371.