1993 Japanese general election

General elections were held in Japan on July 18, 1993 to elect the House of Representatives. The Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), in power since 1955, lost their majority in parliament. An eight-party coalition government was formed and headed by Morihiro Hosokawa, the leader of the Japan New Party (JNP). The election result was profoundly important to Japan's domestic and foreign affairs. It marked the first time since 1955 that the ruling coalition had been defeated, being replaced by a coalition of liberals, centrists and reformists. The change in government also marked a change in generational politics and political conduct, the election was widely seen as a backlash against corruption, pork-barrel spending and a inflated bureaucracy. Proposed electoral reforms also held much influence over the election.[1] Eleven months after the election, the ruling coalition collapsed as multiple parties left the coalition.[2]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

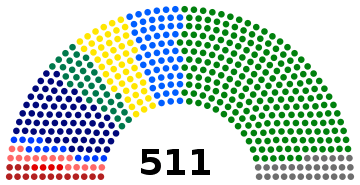

All 511 seats in the House of Representatives of Japan 256 seats needed for a majority | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turnout | 67.26% ( | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Japan |

|

|

|

|

Background

The historic election result, coming after years of scandals, resulted in the LDP losing the premiership for the first time since 1955. The ultimate cause of the LDP's was the defection of key politicians from the party and the consequent formation of two breakaway parties.

Prime Minister Kiichi Miyazawa's dissolution of the Lower House

The election was precipitated by the decision of 39 LDP members - 34 of them from the Hata-Ozawa faction of the LDP, four from the faction led by former Foreign Minister Michio Watanabe, and one from the faction led by former state minister Toshio Komoto[3] - to vote against their own government in favor of a motion of no confidence which was put forward by the opposition in a plenary session on June 18.

This was only the second time since the formation of the LDP that a no-confidence motion had actually succeeded. In the previous occurrence in the May 1980 Lower House election, 69 LDP rebels were not present for the vote, allowing the motion to pass.[3]

This time, all opposition parties voted in favor of the motion, and it carried 255 to 220. Eighteen LDP members’ abstention from the vote signaled their passive support for the motion, thus forcing Prime Minister Kiichi Miyazawa to dissolve the Lower House on the same day and announce a general election for July 18.[3]

Pressure of political reform

At the core of the no-confidence vote was the issue of political reform (seiji kaikaku). The notion of restructuring (risutora) had been extensively discussed in relation to previous “normal scandal elections” which were happening on a frequent basis (in 1976, 1983, and 1990).[4] After the 1988 shares-for-grants Recruit scandal and the 1990 election, Prime Minister Toshiki Kaifu promised political reform; however, intra-party conflict prevented him from keeping his promise. After the 1992 Sagawa scandal and the revelations concerning Shin Kanemaru’s excessiveness in illegal fundraising,[5] Prime Minister Miyazawa again promised political reform and claimed to put anti-corruption measures at the top of his agenda, this time on national television, but failed to deliver.[6] Shin Kanemaru (1914-1996) was an influential figure in Japanese politics; he was the "kingmaker" who exercised his real power behind the scenes and had handpicked at least four prime ministers.[7]

The inability to enact political reform and promptly dealt with corruption issue frustrated the public and a portion of reformist LDP politicians. The faction led by former finance and agriculture minister Tsutomu Hata and political fixer Ichiro Ozawa decided that political reform was important enough and the prospect of winning the election likely enough to risk defecting from the LDP.

The three new reformist parties

A total of 46 LDP defectors formed two new parties. The Hata-Ozawa faction formed the Renewal Party (JRP, Shinseito). Masayoshi Takemura, who had been elected governor of Shiga prefecture with the joint support of the LDP and several opposition parties and was then serving in the House of Representatives in the LDP, along with other nine young and “progressive” LDP members also broke away from the LDP to start the New Party Harbinger (Shinto Sakigake).[8][4]

Additionally, the Japan New Party (JNP, Nihon Shinto), the oldest of the new parties, was formed in May 1992 by Morihiro Hosokawa, formerly an upper house member from the Tanaka faction and governor (1983–91) of Kumamoto prefecture.[8][4]

The LDP's previous losses of parliamentary majority

The LDP had previously lost its majority in the Lower House three times since 1955 (1976, 1979, and 1983) but by very slim margins. Additionally, the LDP had lost its majority in the House of Councillors, the upper house of the National Diet, for the first time in the triennial election for half the seats (36 out of 72) on July 23, 1989 (largely due to the 1988 Recruit Scandal, the introduction of the unpopular Consumption Tax, and the liberalization in the importation of foreign agricultural products),[9] and while it later won the most votes in the 1992 election for the other half of the house, it was not enough to recover the majority.[10]

On each of those occasions, the LDP was able to co-opt a number of independent conservative members or a minor party to form the government. In 1993, however, not enough independent members were willing to join the LDP, and most smaller parties refused to accept coalition with it. Therefore, the formation of a non-LDP coalition became possible for the first time.[8]

Factors in the 1993 Election

The so-called 1955 system was characterized by a one-party dominance of the LDP and a number of other political parties in perennial opposition.[11]

Structural factors conducive to clientelism include fiscal centralization, the pre-1994 electoral system and electoral malapportionment.[12] Fiscal centralization provided a context for the commodification of votes for material gains. The pre-1994 electoral system - Single Non-Transferable Vote in Multimember Districts (SNTV/MMD) - encouraged the proliferation of koenkai networks, money politics, and entrenching clientelistic behaviors in elections. Electoral malapportionment was a result of the pre-1994 electoral system and encouraged politicians to appeal to segments of the population through pork-barrel politics and protectionist policies.[13] Furthermore, the economic recession arising from the real estate bubble at the end of the 1980s and the LDP's failure to adjust severely tarnished its reputation.

1955 system

One-party dominance

Necessity of the one-party dominance

The one-party dominance of the LDP from 1955 to 1993 was a kind of “developmental dictatorship Japanese-style.”[6] It was a necessity for Japan to mobilize and control all human resources with a one-party stable government and an absolute majority in parliament to achieve rapid economic growth of the 1960s. The "mid-size constituency" electoral system allowed Japan to establish a stable government. The LDP, which averaged over 40 percent of the vote in the national elections, could retain slightly more than half the seats in the House of Representatives and the House of Councillors. With this absolute majority of seats in the Diet, the LDP could implement consistent policies effectively, including economic ones.[6]

Explanation for the LDP's grip on power

The LDP was able to retain power for 38 years by changing both its political stance and political leaders according to changes in public opinion and sociopolitical context.[14]

For instance, when Prime Minister Nobusuke Kishi was criticized by the public for his high-handed dealing at the time of the revision of the Japan-United States security Treaty in 1960,[15] the LDP attempted to calm public dissatisfaction by replacing him with Prime Minister Hayato Ikeda, who advocated the governmental slogan of “tolerance and patience” and concentrated on the doubling-of-income policy. When people experienced serious problems arising from the rapid growth of GNP, such as pollution and international trade conflicts at the end of the reign of the Ikeda cabinet, the LDP appointed Eisaku Sato as Ikeda's successor, who advocated “stable development” instead of “rapid growth.”[6]

Implications of the one-party dominance

Nonetheless, this lack of change of government also hindered the process of establishing political responsibility in decision-making and cases of high-profile corruption. When a policy turned out to be a failure, the LDP tried to solve the problem by removing the politician who had promoted the policy instead of examining the cause of its failure.

In the case of the “Reconstruction of the Japanese Archipelago” policy, which created inflation and a money-oriented political culture,[16] the LDP replaced Prime Minister Kakuei Tanaka (considered to be a money politician) with Prime Minister Takeo Miki (well known as a clean uncorrupt politician). When the politician was replaced with another, the former was considered to have paid for what he had done, but the overarching structure which bred the wrong policy, and in this case the "triangle of common interest" or the "iron triangle," was preserved.[6][17]

Furthermore, long one-party rule by the LDP caused a severe struggle for the party presidential elections. Once a person becomes president of the LDP, he or she will automatically be elected prime minister of Japan, so the presidential election of the LDP means the de facto selection of the prime minister.[6]

Consequently, factional politics inside the LDP were more important to LDP leaders than the contest among political parties, as factional leaders in the LDP had to organize a large number of followers and collect substantial political funds in order to win the LDP presidential election and maintain power.[18][6][19]

Iron Triangle

Business sector remained close in contact with the LDP, as it was the sole party which could exercise governmental power. Bureaucrats aligned with the LDP politicians’ suggestions because they barely expected a change of government. Moreover, bureaucrats supported the LDP more actively in order to become members of the Diet after retirement. Each subcommittee of the Policy Affairs Research Council (PARC) of the LDP was assigned to its appropriate government department, also known as the amakudari system.[20][21] In this way the triangle of the LDP, bureaucrats, and business was established.

Factionalism

The LDP was a highly fragmented, decentralized party with independent bases of power in the factions and the zoku (policy ‘tribes’) - veteran politicians who had developed expertise, experience and contacts in a specialized policy area. Large-scale clientelism manifested in individual candidates’ almost exclusive reliance on their own koenkai and their ability to gain votes independent of the party's leader and party label.[18]

Most LDP parliamentarians had built almost unbeatable patronage machines in their areas. Prime Minister Kakuei Tanaka was forced to resign after revelations of his involvement in the Lockheed Scandal.[22] After this retirement, his electoral machine in Niigata continued to be so strong that his daughter, Makiko Tanaka, was elected to the Diet in 1993 at the top of the five-member Niigata electoral district 3. As a result of this type of machine politics, Japan has produced the largest number of "hereditary" parliamentarians in the world.[18]

Fiscal centralization

The primary cause for the emergence of clientelism was tight fiscal centralization in Japan. It is rare for Japanese rural prefectures to have access to substantial fiscal resources, instead relying upon the national government.[23][24] Local prefectures sourced 70 per cent of their revenue from the national government.[25] As a result, the 47 prefectural governments were engaged in a constant struggle to obtain funds from national coffers. Hence, Diet members were not simply representatives of their constituents; they acted as “pipelines” between the national treasury and their respective prefectures.[12]

Electoral malapportionment

Correcting the rural-urban imbalance and vote-value disparity is one objective of political reform. The pre-1994 electoral system was advantageous for rural areas where the LDP had been particularly strong in terms of support base, as the LDP helped protect the agriculture industry and social security for them in return. It is in rural Japan that the local support groups (koenkai) have been handed down from one generation of Diet member to another. The support groups, in turn, ensured LDP's grip on power.[26] Additionally, the village association (burakukai) can deliver bloc votes to conservative candidates.[18]

Demobilization of soldiers, wartime destruction of industry and repatriation of Japanese from Manchuria had swelled the rural population, but the later flight from the countryside to cities due to industrialization meant that the votes of urban constituency declined comparatively in value without electoral redistribution.

The weight of the rural vote was exaggerated due to the drawing of electoral districts. The electoral districts up to 1993 were drawn in the immediate postwar period and had not redrawn since. The Diet had only made some minor adjustments in the past, adding a few seats in urban areas and reducing some rural ones.[18][27] Since 1964, voters in urban constituencies had filed 10 lawsuits seeking fairer distribution of Diet seats. The Supreme Court declared “constitutional” the 5.85-to-1 disparity in the 1986 election, but it ruled the 6.59-to-1 ratio in the 1992 balloting as being “in an unconstitutional state” - implying that it effectively violated the constitutionally guaranteed equality of voting rights.[28]

The most immediate adjustments prior to 1993 (December 1992) cut out ten rural seats and added nine urban ones, thus reducing the total membership of the lower house from 512 to 511. Despite this change, the vote value in rural and urban areas remained highly disproportionate, with a ratio of 1:2.84.[18][27] Under the current Constitution, the maximum variation in the numbers of voters per seat was 1:1.5.[29] The sharp disparity in the value of votes was a grave issue that distorted the representation of popular will in the Diet. Thus, the political reform needed to include reducing inequalities.

Corruption

The other aspect of political reform was related to the ever-increasing visibility of corruption in Japanese politics, which is ascribed to the electoral system. In the multi-seat electoral constituencies, two to six members were elected from the same electoral district. As it allowed for occupying a greater number of seats in the lower house than the total number of electoral districts, this system encouraged parties to run multiple candidates in the same district. Thus, individual politicians were invariably pressed to pursue a personal campaign strategy to differentiate themselves from even those from the same party,[30] characterizing the LDP's intra-party competition and leading to reliance on pork-barrel policy and candidate-based voting rather than on party-centered and issue-based electoral battles.[18][31]

The use of money to coordinate votes was acutely felt amongst Japanese constituents, where party affiliations were seldom strong,[32] and roughly half the electorate was undecided.[24] The LDP candidates’ extensive contacts with Japanese business facilitated their ability to provide larger material benefits. This provided the LDP with a tremendous advantage, but also increased the temptation for corruption.[33]

Lockheed Scandal

In June 1976, Prime Minister Kakuei Tanaka was arrested for accepting a bribe of 500 million yen from the Lockheed Company. The LDP was severely criticized and, thus, suffered a decline in its seats in the Diet from 264 to 249 and lost its absolute majority in the House of Representatives election on December 5, 1976.

Recruit Scandal

The scandal was revealed on June 18, 1988, during Prime Minister Noboru Takeshita’s premiership. The chairman of the Recruit Company granted a special favor to politicians, local officials, and journalists by allowing them to buy stock of the Recruit Cosmos Company before it was listed. When listed as an over-the-counter issue, its value increased enormously, and those who had bought it made gigantic profits.

Since almost all of the Takeshita cabinet including the prime minister, finance minister, and LDP secretary was involved in the scandal, the party could not find an appropriate prime minister as a replacement. On April 25, 1989 Prime Minister Takeshita resigned.

The Recruit scandal was the start of the collapse of the LDP's stable one-party rule in Japan.[18]

Political funding

Political funding was yet another controversial issue surrounding the electoral reform. To serve their constituencies well, one of the major tasks of LDP politicians was to raise enormous amounts of political funds, most notably from business sector.

Despite modifications of Political Funds Control Law made in 1975 as in politicians were required to make public the names of donors who give more than one million yen to any one of a candidate's support organizations, the law still had several loopholes. Numerous organizations were set up to absorb donations from various sources. Cases of high-ranking politicians indicted on charges of corrupt practices related to their election funds abounded, although very few were convicted and sentenced.

Sagawa Kyubin Scandal

The most serious case, the 1992 Sagawa Kyubin scandal, was that brought against the LDP chairman of the largest LDP faction Keiseikai and former vice-president, Shin Kanemaru, who was arrested in March 1993. He was charged of evading taxes on a massive personal fortune, 500 million yen, a large part of which he allegedly obtained through secret donations from the parcel delivery firm Tokyo Sagawa Kyubin.[18]

Although the Japanese public was already used to the idea of political bribes, which were even allowed as a tax reduction under the euphemism “usage unknown money” (shitofumeikin), there was a common acceptance that those involved should not be “too greedy.” The revelations in this case exceeded public tolerance.[18]

Economic downturn

The LDP could maintain support thanks to the party's successful management of economic development. However, “bubble economy” resulted in a call for political change.

Bubble economy is the abnormal rise in share values and land prices after the Plaza Accord of September 22, 1985 produced a dramatic appreciation of the yen. This, in turn, triggered a rapid growth in capital investment and consumption, and asset prices skyrocketed as a result. When the government tightened monetary policy to counter these effects, share values and land prices fell. Consequently, financial institutions, especially securities companies, suffered losses. Since 1991, Japanese economy had been struggling to adjust to the government's liberalization measures, and recovery was still way off.[34]

Campaign

During the two-week official election campaign period, almost all candidates spoke about political reform, though none made it clear what that meant or how it was going to be achieved. "Change" was the key word in the election - changing the corrupt practices as well as the ruling status of the LDP.[35]

Media and Public opinion

The media and wire services (Asahi Shinbun, NHK, Kyodo News Service) unanimously predicted that the LDP would lose its majority in the Diet. Even though a Nikkei poll conducted between June 25–27 showed that support for the LDP had dropped from 43.8% to 28.6% and that only 21.9% of respondents planned to vote for the LDP, 32.1% still supported an LDP-led coalition. JRP leader Hata was the most popular choice for prime minister, while both former LDP Prime Minister Toshiki Kaifu and LDP Deputy Prime Minister Masaharu Gotada polled well.[36]

Thus, the downfall of the LDP was expected. What was not clear was the make-up of the coalition that would emerge.[37]

The LDP

The LDP's campaign theme was stable single-party rule. LDP Secretary-General Seiroku Kajiyama said “I don’t think Japan’s political business will move ahead under a coalition of forces with different opinions on security and foreign relations issues.” Former LDP Foreign Minister Michio Watanabe predicted that, in the event of an opposition victory, Japan would resemble Italy: “the Cabinet will be changing all the time, the economy will be in disarray, the number of thieves and beggars will increase, and so will robberies and rapes.”[36]

The opposition

The emergence of the non-LDP coalition government resulted from agreement on certain basic principles by conservative, centrist, and leftist opposition groups. One of the basic shared line of thinking was that the LDP's hold on the government should be broken.[37] The main issue for the opposition parties was electoral reform. Additionally, there was general consensus on some other issues, including tax cuts which are needed to stimulate economic growth and anti-corruption measures. The Social Democratic Party of Japan (SDPJ) even relaxed several long-held positions - that was recognition of the constitutionality of Japan's Self-Defense Force, acceptance of the peace treaty with the Republic of Korea and approval of nuclear energy until alternatives are developed - so as to “put an end to the LDP’s monopoly of politics and establish a coalition government to accomplish political reform,” according to SDPJ Chairman Sadao Yamahana.[36]

Nonetheless, the oppositions varied on trade liberalization; only the JNP was in favor of opening Japan's rice market to imports.[36][38] Each of the parties issued campaign pledges which tended to be vague, as was usual in Japanese elections where issues often had little influence on voting behavior.

The JNP's platform was the most detailed, covering the following areas: (1) political ethics, political reform; (2) international contribution; (3) constitution; (4) diplomacy, defense; (5) economy, tax system; (6) agriculture policy; (7) environment; (8) education, welfare.[36]

Results

The ruling Liberal Democratic Party lost its overall majority for the first time since 1983 and also failed to form the government for the first time since 1955. The 223 seats in the lower house the LDP was able to gain was 52 fewer than what the party held a month before and 33 votes short of a majority in the 511-member body.[39] More than fifty LDP members forming the Shinseitō and the Sakigake parties had denied the LDP the majority needed to form a government.

In a normal process of coalition formation, the LDP as the largest party was expected to be able to coalesce with any single party except the Democratic Socialist Party (DSP). However, in the event, the logic of coalition formation was overwhelmed by the prospect of the dissatisfied electorate who was demanding change and would refuse any alliance with the then-incumbent LDP.[40]

Although no longer holding a majority in the House of Representatives, the LDP remained the strongest party, both in terms of the popular vote and the number of seats gained. With its 223 seats in a 511-member house, the LDP had the opportunity to act as a real opposition, a very different situation from the past 38 years when the largest opposition party, the SDPJ, was unable to pass even the one-third mark.[41] Komeito, DSP, USDP and JCP maintained their positions.

On the other hand, the big loser was the SDPJ which lost almost half of its seats, while the big winner was the JNP.[42] With 134 members prior to the dissolution of the house, the socialists ended up with just 70 seats, an all-time low for the party since it was established as a unified party in 1955. The voters who previously had cast their votes for the socialists in protest against the LDP now had the choice of three "conservative" parties other than the LDP.[41]

The election was marked by a considerable degree of continuity, reflecting the basically conservative nature of Japanese society, the endurance of personal fiefdoms, the strengthening of conservative and centrist forces and a corresponding weakening of the leftist parties.[41][42] The current political change was not so much a product of the opposition's strength as it was of the LDP's weaknesses and internal dissension and the leader's incompetency regarding keeping the various factions together. This time, the LDP was not able to exercise its long-practiced flexible stance; instead, its rigid stance exposed weaknesses and became the strengths of the conservatives who defected from it.[41]

| ||||||||

| Alliances and parties | Candidates | Votes[45] | % | +/- | Seats | +/- (last gen. election) | +/- (dissolution) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) Jiyūminshutō | 285 | 22,999,646 | 36.62% | 223 | ||||

| Japanese Socialist Party (JSP) Nihon Shakaitō | 142 | 9,687,588 | 15.43% | 70 | ||||

| Shinseito Shinseitō ("Renewal Party") | 69 | 6,341,364 | 10.10% | ( | 55 | ( | ||

| Komeito Kōmeitō ("Justice Party") | 54 | 5,114,351 | 8.14% | 51 | ||||

| Japan New Party (JNP) Nihon Shintō | 57 | 5,053,981 | 8.05% | ( | 35 | ( | ||

| Democratic Socialist Party (DSP) Minshatō | 28 | 2,205,682 | 3.51% | 15 | ||||

| New Party Sakigake Shintō Sakigake ("New Party Harbinger") | 16 | 1,658,097 | 2.64% | ( | 13 | ( | ||

| Social Democratic Federation (SDF) Shakaiminshu Rengō | 4 | 461,169 | 0.73% | 4 | ||||

| Anti-LDP and Anti-communist opposition | 370 | 30,522,232 | 48.60% | 243 | ||||

| Japanese Communist Party (JCP) Nihon Kyōsantō | 129 | 4,834,587 | 7.70% | 15 | ||||

| Others | 62 | 143,486 | 0.23% | ( | 0 | ( | ||

| Independents | 109 | 4,304,188 | 6.85% | 30 | ||||

| Total (turnout 67.26%) | 955 | 62,804,145 | 100.00% | 511 | (reapportionment) |

|||

Post-election

New government

The LDP attempted to delay the handover. As the largest party by far, it demanded the right to appoint the Speaker in accordance with parliamentary convention. Additionally, LDP's new Secretary-General, Yoshiro Mori, pressed for an extension of the planned 10-day Diet session to enable economic issues to be debated, an area in which the party had overwhelming expertise. Both moves were rejected by the coalition.[46]

The coalition partners, meanwhile, unanimously settled on JNP Chairman Morihiro Hosokawa as Japan's new Prime Minister, although the more experienced Tsutomu Hata was initially preferred by the SDPJ and Komeito. Political reform was on the top of the new government's agenda.

Political reform

The Hosokawa coalition cabinet put forward a political reform on September 17, 1993, which proposed (1) changes in the electoral system for the House of Representatives and the introduction of a combined single-member constituency system and a proportional representation system; (2) strengthening the regulation of political funding; (3) public financing of party activities; and (4) the establishment of the Constituencies Boundaries Committee. The LDP also presented their own political reform bills; on October 5 to the Diet. The LDP bills also adopted the simple combined system of a single-member constituency and proportional representation.[6]

The bill was passed in the House of Representatives with modifications on November 18, 1993. It was rejected, however, in the House of Councillors on January 22, 1994 in spite of the coalition parties’ majority in the House.

On January 29, 1994, political reform bills which had been discussed in Japanese politics for six years were finally passed through both Houses of the Diet on the basis of last-minute agreements achieved a day before the end of the session between Yohei Kono, president of the LDP, and prime minister Hosokawa. The modified bills were passed by the House of Representatives on March 1 with unanimous votes except for the Japan Communist Party (JCP), and by the House of Councillors on March 4, 1994.[6]

The LDP regains power

Although the Hosokawa cabinet received the highest popularity rating (around 70%) ever enjoyed by a new cabinet in Japan, the coalition appeared to be a fragile and short-term one. SDPJ Chairman Yamahana's statement that the coalition was working as an "emergency government" with an aim toward completing the task of political reform reinforced the possibility of elections in the near future, which was 10 months later. Hosokawa stated that he would "take responsibility" (i.e., resign) if electoral reform was not introduced by the end of the year, and if it was, a new system would require new elections to be held under it.

The coalition government collapsed after 10 months when the Socialist Party and New Party Sakigake left the government. The Socialist Party decided to form a Grand coalition government with Liberal Democratic Party in 1994, returning the LDP to power.

References

- "Japanese politics and the July 1993 election". ResearchGate. Retrieved 2019-06-10.

- "Chapter Sixteen Period of President Kono's Leadership | Liberal Democratic Party of Japan". www.jimin.jp. Retrieved 2019-06-10.

- Jain, Purnendra C. (November 1993). "A New Political Era in Japan: The 1993 Election" (PDF). Asian Survey. 33 (11): 1071–1082. doi:10.2307/2645000. ISSN 0004-4687. JSTOR 2645000.

- Reed, Steven R. (1994-03-01). "The Japanese general election of 1993". Electoral Studies. 13 (1): 80–82. doi:10.1016/0261-3794(94)90011-6. ISSN 0261-3794.

- Woodruff, John E. "Fallen politician in Japan had amassed $51 million". baltimoresun.com. Retrieved 2019-01-27.

- Shiratori, Rei (1995). "SAGE Journals: Your gateway to world-class journal research". International Political Science Review. 16: 79–94. doi:10.1177/019251219501600106.

- "Shin Kanemaru | Japanese politician". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2019-01-28.

- Jain, Purnendra C. (November 1993). "A New Political Era in Japan: The 1993 Election" (PDF). Asian Survey. 33 (11): 1071–1082. doi:10.2307/2645000. ISSN 0004-4687. JSTOR 2645000.

- Reed, Steven R.; Baerwald, Hans H.; Fukui, Haruhiro; Masayuki, Fukuoka; Takashi, Inoguchi; Ikuo, Kabashima; Yoshiaki, Kobayashi; Stockwin, J. A. A. (1989). "Predictions of the 1989 Japanese Election: Introduction". Journal of Japanese Studies. 15 (2): 531. doi:10.2307/132384. ISSN 0095-6848. JSTOR 132384.

- Baerwald, Hans H. (September 1989). "Japan's House of Councillors Election: A Mini-Revolution?". Asian Survey. 29 (9): 833–841. doi:10.1525/as.1989.29.9.01p0302f. ISSN 0004-4687.

- A., Scalapino, Robert (1971). Parties and politics in contemporary Japan. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520011328. OCLC 877997679.

- Norris, Michael J. (2010). "The Liberal Democratic Party in Japan: Explaining the Party's Ability to Dominate Japanese Politics". Inquiries Journal. 2 (10).

- Reed, Steven R. (2010), "The Liberal Democratic Party", The Routledge Handbook of Japanese Politics, Routledge, doi:10.4324/9780203829875.ch2, ISBN 9780203829875

- Woodall, Brian; Calder, Kent E. (1990). "Crisis and Compensation: Public Policy and Political Stability in Japan, 1949-1986". Pacific Affairs. 63 (1): 106. doi:10.2307/2759834. ISSN 0030-851X. JSTOR 2759834.

- "6-13 1960 signing of new Japan-U.S. Security Treaty | Modern Japan in archives". www.ndl.go.jp. Retrieved 2019-01-27.

- Leggett, David (1995). "Japan's money politics". Public Money & Management. 15: 25–28. doi:10.1080/09540969509387852.

- "Iron Triangle - Japanese Political Economy - Wiki.nus". wiki.nus.edu.sg. Retrieved 2019-01-27.

- Jain, Purnendra C. (November 1993). "A New Political Era in Japan: The 1993 Election" (PDF). Asian Survey. 33 (11): 1071–1082. doi:10.2307/2645000. ISSN 0004-4687. JSTOR 2645000.

- BROWNE, ERIC C.; KIM, SUNWOONG (January 2003). "Factional rivals and electoral competition in a dominant party: Inside Japan's Liberal Democratic Party, 1958-19901". European Journal of Political Research. 42 (1): 107–134. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.00077. ISSN 0304-4130.

- 1933-, Wright, Maurice (2002). Japan's fiscal crisis : the Ministry of Finance and the politics of public spending, 1975-2000. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199250530. OCLC 48450834.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- "Amakudari - Japanese Political Economy - Wiki.nus". wiki.nus.edu.sg. Retrieved 2019-01-27.

- Lohr, Steve; Times, Special To the New York (1983-10-12). "Tanaka Is Guilty in Bribery Trial". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-01-27.

- Fukui, Haruhiro; Fukai, Shigeko N. (March 1996). "Pork Barrel Politics, Networks, and Local Economic Development in Contemporary Japan". Asian Survey. 36 (3): 268–286. doi:10.1525/as.1996.36.3.01p0116g. ISSN 0004-4687.

- Scheiner, Ethan (2005), "Introduction: The Puzzle of Party Competition Failure in Japan", Democracy Without Competition in Japan, Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–6, doi:10.1017/cbo9780511610660.001, ISBN 9780511610660

- Scheiner, Ethan (September 2005). "Pipelines of Pork". Comparative Political Studies. 38 (7): 799–823. doi:10.1177/0010414005277020. ISSN 0010-4140.

- Carlson, Matthew M. (August 2006). "Electoral Reform and the Costs of Personal Support in Japan". Journal of East Asian Studies. 6 (2): 233–258. doi:10.1017/s1598240800002319. ISSN 1598-2408.

- Horiuchi, Yusaku; Saito, Jun (October 2003). "Reapportionment and Redistribution: Consequences of Electoral Reform in Japan". American Journal of Political Science. 47 (4): 669–682. doi:10.1111/1540-5907.00047. ISSN 0092-5853.

- "An equal value for every vote". The Japan Times. 2000-09-16. Retrieved 2019-01-27.

- Hasebe, Y. (2007-04-01). "The Supreme Court of Japan: Its adjudication on electoral systems and economic freedoms". International Journal of Constitutional Law. 5 (2): 296–307. doi:10.1093/icon/mom004. ISSN 1474-2640.

- Reed, Steven R. (March 1994). "Democracy and the personal vote: A cautionary tale from Japan". Electoral Studies. 13 (1): 17–28. doi:10.1016/0261-3794(94)90004-3. ISSN 0261-3794.

- 1945-, Hrebenar, Ronald J. (1986). The Japanese party system : from one-party rule to coalition government. Westview Press. OCLC 720865963.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- "Japanese democracy: power, coordination, and performance". Choice Reviews Online. 35 (1): 35–0538–35–0538. 1997-09-01. doi:10.5860/choice.35-0538. ISSN 0009-4978.

- Bettcher, Kim Eric; Stockwin, J. A. A. (2000). "Governing Japan: Divided Politics in a Major Economy". Pacific Affairs. 73 (2): 291. doi:10.2307/2672198. ISSN 0030-851X. JSTOR 2672198.

- "Rising Sun, Setting Sun: British and Malayan Perspectives on the Japanese Occupation of Malaya in Fiction", Representations of War in Films and Novels, Peter Lang, 2016, doi:10.3726/978-3-653-06092-8/16, ISBN 9783653060928

- Jain, Purnendra C. (November 1993). "A New Political Era in Japan: The 1993 Election" (PDF). Asian Survey. 33 (11): 1071–1082. doi:10.2307/2645000. ISSN 0004-4687. JSTOR 2645000.

- Michael., Underdown (1993). Japanese politics and the July 1993 election : continuity and change. Dept. of the Parliamentary Library. OCLC 223737877.

- Jain, Purnendra C. (November 1993). "A New Political Era in Japan: The 1993 Election" (PDF). Asian Survey. 33 (11): 1071–1082. doi:10.2307/2645000. ISSN 0004-4687. JSTOR 2645000.

- Sanger, David E. (1993-12-08). "Japanese Reluctantly Agree to Open Rice Market". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-01-27.

- Reid, T.R. (July 19, 1993). "Japan's top party loses its majority". The Washington Post. Retrieved January 28, 2019.

- Reed, Steven R. (1994-03-01). "The Japanese general election of 1993". Electoral Studies. 13 (1): 80–82. doi:10.1016/0261-3794(94)90011-6. ISSN 0261-3794.

- Jain, Purnendra C. (November 1993). "A New Political Era in Japan: The 1993 Election" (PDF). Asian Survey. 33 (11): 1071–1082. doi:10.2307/2645000. ISSN 0004-4687. JSTOR 2645000.

- Michael., Underdown (1993). Japanese politics and the July 1993 election : continuity and change. Dept. of the Parliamentary Library. OCLC 223737877.

- Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (MIC), Statistics Department, Long-term statistics Archived 2015-02-15 at the Wayback Machine, chapter 27: Public servants and elections, sections 27-7 to 27-10 Elections for the House of Representatives.

- Inter Parliamentary Union

- Decimals from fractional votes (anbunhyō) rounded to full numbers

- Jain, Purnendra C. (November 1993). "A New Political Era in Japan: The 1993 Election" (PDF). Asian Survey. 33 (11): 1071–1082. doi:10.2307/2645000. ISSN 0004-4687. JSTOR 2645000.

See also

- Koenkai

- 1994 Electoral system Reform

- Clientelism

- Money politics in Japan

- Corruption in Japan

- Lockheed Bribery Scandal

- Recruit Scandal

- Electoral system

- Fiscal centralization