Iwate Prefecture

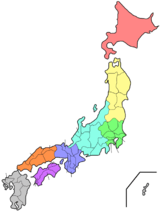

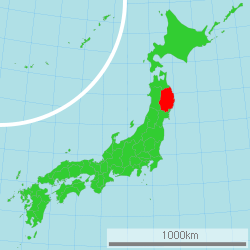

Iwate Prefecture (岩手県, Iwate-ken) is a prefecture of Japan located in the Tōhoku region of Honshu.[1] It is the second-largest Japanese prefecture at 15,275 square kilometres (5,898 sq mi), with a population of 1,229,432 (as of 1 June 2019). Iwate Prefecture borders Aomori Prefecture to the north, Akita Prefecture to the west, and Miyagi Prefecture to the south.

Iwate Prefecture 岩手県 | |

|---|---|

| Japanese transcription(s) | |

| • Japanese | 岩手県 |

| • Rōmaji | Iwate-ken |

Symbol | |

| |

| Country | Japan |

| Region | Tōhoku |

| Island | Honshu |

| Capital | Morioka |

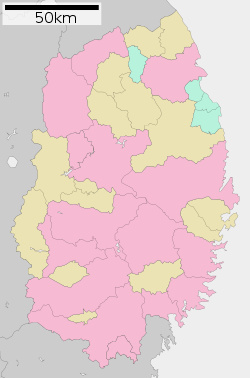

| Subdivisions | Districts: 10, Municipalities: 33 |

| Government | |

| • Governor | Takuya Tasso |

| Area | |

| • Total | 15,275.01 km2 (5,897.71 sq mi) |

| Area rank | 2nd |

| Population (1 June 2019) | |

| • Total | 1,229,432 |

| • Rank | 32nd |

| • Density | 80/km2 (210/sq mi) |

| ISO 3166 code | JP-03 |

| Website | www |

| Symbols | |

| Bird | Green pheasant (Phasianus colchicus) |

| Fish | Chum salmon (Oncorhynchus keta) |

| Flower | Paulownia tree (Paulownia tomentosa) |

| Tree | Nanbu red pine (Pinus densiflora) |

Morioka is the capital and largest city of Iwate Prefecture; other major cities include Ichinoseki, Ōshū, and Hanamaki.[2] Located on Japan's Pacific Ocean coast, Iwate Prefecture features the easternmost point of Honshu at Cape Todo, and shares the highest peaks of the Ōu Mountains—the longest mountain range in Japan—at the border with Akita Prefecture. Iwate Prefecture is home to famous attractions such as Morioka Castle, the Buddhist temples of Hiraizumi including Chūson-ji and Mōtsū-ji, the Fujiwara no Sato movie lot and theme park in Ōshū, and the Tenshochi park in Kitakami known for its huge, ancient cherry trees. Iwate has the lowest population density of any prefecture outside Hokkaido, 5% of its total land area having been designated as National Parks.

Name

There are several theories about the origin of the name "Iwate", but the most well known is the tale Oni no tegata, which is associated with the Mitsuishi or "Three Rocks" Shrine in Morioka. These rocks are said to have been thrown down into Morioka by an eruption of Mt. Iwate. According to the legend, there was once a devil who often tormented and harassed the local people. When the people prayed to the spirits of Mitsuishi for protection, the devil was immediately shackled to these rocks and forced to make a promise never to trouble the people again.[3] As a seal of his oath, the devil made a handprint on one of the rocks, thus giving rise to the name Iwate, its direct translation being "rock hand". Even now after a rainfall, it is said that the devil's hand print can still be seen there.

Culture

There are many present-day cultural foods popularly eaten in Iwate Prefecture, some of which include walnuts, wanko soba (meaning "bowl noodles") and hittsumi-jiru (meaning "pull and tear", in reference to the way the dough is pulled and torn into oval shapes before being turned into noodles).[4] Iwate's prefectural capital Morioka is also popular for its apples, blooming in May and ready for harvest from September to November.[5]

Japanese poet Matsuo Bashō visited Iwate and wrote about it in the journey described in his major work Oku no Hosomichi. He was especially inspired by the town of Hiraizumi.

History

While the entire island of Honshū was claimed by the Japanese, or Yamato, government from earliest times as a sort of divine right or manifest destiny, the imperial forces were unable to occupy any part of what would become Iwate until 802 when two powerful Emishi leaders, Aterui and More, surrendered at Fort Isawa.

The area now known as Iwate Prefecture was inhabited by the Jōmon people who left their artifacts throughout the prefecture. For example, a large number of burial pits from the Middle Jōmon Period (2,800–1,900 BC) have been found in Nishida. Various sites from the Late Jōmon Period (1,900–1,300 BC) including Tateishi, Makumae and Hatten contain clay figurines, masks and ear and nose shaped clay artifacts. The Kunenbashi site in Kitakami City has yielded stone "swords", tablets and tools as well as clay figurines, earrings and potsherds from the Final Jōmon Period (1,300–300 BC).

The earliest mention of a Japanese presence dates to about 630 when the Hakusan Shrine was said to have been built on Mt. Kanzan in what is now Hiraizumi. At this time various Japanese traders, hunters, adventurers, priests and criminals made their way to Iwate. In 712 the province of Mutsu, containing all of Tōhoku, was divided into Dewa Province, the area west of the Ou Mountains and Mutsu Province. In 729 Kokuseki-ji Temple was founded in what is now Mizusawa Ward, Oshu City by the itinerant priest Gyōki.

Little is known about relations between these Japanese frontiersmen and the native Emishi but in 776 they took a turn for the worse when large forces of the Yamato army invaded Iwate attacking the Isawa and Shiwa tribes in February and November of that year. More fighting occurred the next and following years but mostly in Dewa and the area south of present-day Iwate prefecture. This situation continued until March 787 when the Yamato army suffered a disastrous defeat in the Battle of Sufuse Village in what is now Mizusawa Ward, Oshu City. There the Emishi leaders and Aterui leading a large cavalry force trapped the Yamato infantry and pushed them into the Kitakami River where their heavy armour proved deadly. Over 1,000 soldiers drowned that day. The Japanese general Ki no Asami Kosami was "rebuked" by the Emperor Kanmu when he returned to Kyoto.

Since the Japanese could not win on the battlefield they resorted to other means to conquer the Emishi. Trade for superior quality iron wares and sake made the Emishi dependent on the Japanese for these valuable goods. Bribes were offered to the Emishi leaders in the form of Japanese citizenship and rank if they would defect. Finally a campaign of burning crops and kidnapping the Emishi women and children and relocating them to Western Japan was adopted. Many a stout warrior gave up the fight to join his family again.

In 801, Sakanoue no Tamuramaro began a new campaign against the Isawa Emishi having moderate success. Finally on 15 April 802 the Emishi leaders More and Aterui surrendered with some 500 warriors. The captives were taken to Kyoto for an audience with the emperor and beheaded at Moriyama in Kawachi Province against the wishes of General Sakanoue. This act of cruelty enraged the Emishi leading to another twenty or more years of fighting.

After the surrender numerous forts were built on the Chinese model along the Kitakami River. In 802, Fort Isawa was built in what is now Mizusawa Ward, Oshu City, in 803, Fort Shiwa was built in what is now Morioka City, and in 812 Fort Tokutan was built also in Morioka.

In the latter part of the Heian period, the town of Hiraizumi in what is now southern Iwate became the capital of the Northern Fujiwara. The warrior Minamoto no Yoshitsune fled here after the Genpei War.[6]

Until the Meiji Restoration, the area of Iwate prefecture was part of Mutsu Province.[7]

Iwate Prefecture was created in 1876, in the aftermath of the Boshin Civil War, which heralded the beginning of the Meiji Restoration.

Geography

City Town Village

Iwate faces the Pacific Ocean to the east with sheer, rocky cliffs along most of the shoreline interrupted by a few sandy beaches. The border with Akita Prefecture on the west is generally formed by the highest points of the Ōu Mountains. Aomori Prefecture is to the north and Miyagi Prefecture is to the south.

The Ōu mountains on the west still contain active volcanoes such as Mt. Iwate (at 2,038 metres (6,686 ft) the highest point in the prefecture) and Mt. Kurikoma (1,627 metres (5,338 ft)). But the Kitakami Mountains running through the middle of the prefecture from north to south are much older and have not been active for thousands of years. Mt. Hayachine (1,917 metres (6,289 ft)) lies at the heart of the Kitakami range.

Besides these two mountain ranges and the rugged coastline, the prefecture is characterized by the Kitakami River which flows from north to south between the Ōu and Kitakami mountain ranges. It is the fourth longest river in Japan and the longest in Tōhoku. The basin of the Kitakami is large and fertile providing room for the prefecture's largest cities, industrial parks and farms.

In the past Iwate has been famous for its mineral wealth especially in the form of gold, iron, coal and sulfur but these are no longer produced. There is still an abundance of hot water for onsen, or hot springs, which is the basis of a thriving industry. The forests of the prefecture are another valuable resource. Before World War II the forests were mainly composed of beech but since then there has been a huge swing towards the production of faster growing Japanese cedar. Recently, though, there has been a push to restore the original beech forests in some areas.

As of 31 March 2019, 5% of the total land area of the prefecture was designated as Natural Parks, namely Towada-Hachimantai and Sanriku Fukkō National Parks; Kurikoma and Hayachine Quasi-National Parks; and Goyōzan, Hanamaki Onsenkyō, Kuji-Hiraniwa, Murone Kōgen, Oritsume Basenkyō, Sotoyama-Hayasaka Heights, and Yuda Onsenkyō Prefectural Natural Parks.[8][9]

Towns and villages

These are the towns and villages in each district:

Mergers

Economy

Iwate's industry is concentrated around Morioka and specializes in semiconductor and communications manufacturing.

As of March 2011, the prefecture produced 3.9% of Japan's beef and 14.4% of broiler chickens.[10] In 2009, 866 tons of dolphins and whales were harvested off the coast of Iwate, accounting for more than half of Japan's total catch of 1,404 tons.[11]

Demographics

The current population of Iwate as of 1 October 2007 is 1,363,702 consisting of 651,730 males and 711,972 females.

The earliest census records date from 1907 when the population of Iwate stood at 770,406 with 389,490 males and 380,916 females. This is also the only census to record more males than females.

In 1935, Iwate's population surpassed a million reaching 1,045,793.

In 1960, the population of the prefecture reached its all time high before or since at 1,449,207.

In 1985, the population of the prefecture reached its second all-time high before or since at 1,433,611.

The census of 1950 saw the most births in the prefecture with 45,968 reported. Since then there has been an almost steady decline to 10,344 births in 2007. The greatest number of deaths were reported in 1945 with a total of 32,614. The number of deaths declined steadily until 1980 when the fewest deaths were recorded, 9,892. Since then the number of deaths has increased gradually to 14,774 in 2007.

Thanks to improvements in medicine the number of infants dying at birth has declined from a high of 4,246 in 1950 to just 332 in 2007.

The number of marriages in the prefecture has also declined from a high of 13,055 in 1950 to an all-time low of 6,354 in 2007.

Per Japanese census data,[12] and [13], Iwate prefecture has had negative population growth since 1985

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1890 | 655,400 | — |

| 1920 | 846,000 | +29.1% |

| 1930 | 976,000 | +15.4% |

| 1940 | 1,096,000 | +12.3% |

| 1950 | 1,347,000 | +22.9% |

| 1960 | 1,449,000 | +7.6% |

| 1970 | 1,371,000 | −5.4% |

| 1980 | 1,422,000 | +3.7% |

| 1990 | 1,417,000 | −0.4% |

| 2000 | 1,416,180 | −0.1% |

| 2010 | 1,330,147 | −6.1% |

| 2020 | 1,229,432 | −7.6% |

Natural disasters

On 13 July 869, a magnitude 8.6 earthquake and tsunami struck the coast of Iwate.

On 14 November 1230, volcanic activity was reported.

On 2 December 1611, a magnitude 8.1 earthquake and tsunami were reported to have killed over 3,000 horses and people.

In 1662 Morioka and its suburbs were hit by a large flood leaving 1,000 dead.

Volcanic activity was reported on Mt. Iwate on 23 March 1686 and 14 April 1687.

In 1700, a tsunami from the 1700 Cascadia earthquake struck Iwate Prefecture. No records from North America exist, but the event was reconstructed using Japanese records.

On 13 May 1717, The Hanamaki area was struck with a magnitude 7.6 earthquake opening cracks in the ground everywhere. There was also widespread destruction of houses and shops.

In Nanbu-han alone, 49,594 people starved to death in the famine of 1755.

Severe famines continue from 1783 to 1787 and again from 1832 to 1838.

Cholera outbreaks occurred in August 1879, in Miyako and Kuji.

In July 1882, a cholera outbreak in Kamaishi left 302 dead and warnings about drinking water were posted throughout the prefecture.

In April 1884, there was another outbreak of cholera in Kamaishi.

In September 1886, cholera outbreaks throughout Iwate left 312 dead.

On 15 June 1896, at 7:32 am, a magnitude 8.5 earthquake struck offshore. The ensuing tsunami sent waves onto the coast of Iwate at Yoshihama, in what is now Sanriku town, reaching 24 metres (79 ft) in height. 18,158 people died in Iwate alone while some 10,000 homes were destroyed. Fishermen fishing the ocean about 20 miles (32 km) offshore felt nothing, then returning home the next morning found the shore littered with their homes and the bodies of their loved ones.

In September 1899, dysentery spread throughout the prefecture killing 2,070 people.

There was a widespread crop failure due to violent storms in September 1902. Only 32,900 tons of rice were produced in Iwate, just 30% of the previous year's harvest.

In 1905, there was again a massive crop failure due to heavy rain and cold leading to famine in 1906. People were reduced to eating straw, acorns and roots.

In 1919, a small eruption occurred at Nishi-Iwate.[14]

On 3 March 1933, a magnitude 8.1 earthquake struck offshore killing 3,008 people and destroying 7,479 homes. This is the fifth worst earthquake in Japan since 1923.

Small explosions shook Mt. Iwate throughout 1934 and 1935.

In August 1957, there was volcanic activity on Mt. Kurikoma.

There was volcanic activity on Mt. Akita-Komagatake from September to December 1970 with lava flows visible from Morioka.

In 2003, earthquakes struck on 26 May (M7.0 off the coast of Kesennuma, Miyagi Prefecture), 25 July (three jolts of M5.5, 6.2 and 5.3 in southern Iwate) and 26 September (M8.3 in Hokkaido but strongly felt in Iwate).

At 8:43 am on 14 June 2008, Iwate was struck by a 7.2 magnitude earthquake. The epicenter was about 8 kilometres (5.0 mi) underground in Ichinoseki City. Thirteen deaths were reported and massive landshifts occurred in Northern Miyagi and Southern Iwate.

On Friday, 11 March 2011, a magnitude 9.0 earthquake hit this area, triggering a large tsunami and extensive damage. The highest run up of water was measured at over 38 metres (125 ft).[15] The disaster destroyed 9,672 of the prefecture's fishing vessels, damaged 108 of 111 ports, wiped out nearly all of the prefecture's fish processing centers, and caused ¥371.5 billion in damage to the prefecture's fishing industry.[16]

Tourism

.jpg) A panorama view of Jōdogahama in Miyako city.

A panorama view of Jōdogahama in Miyako city..jpg) A view of Tono Country Village.

A view of Tono Country Village. The Takuboku Ishikawa Memorial Museum in Morioka.

The Takuboku Ishikawa Memorial Museum in Morioka. Sansa Odori, one of famous for summer event in northern Honshu.

Sansa Odori, one of famous for summer event in northern Honshu.

The Pokémon Geodude was announced as the tourism ambassador to Iwate Prefecture.[17] The character was chosen for being a rock type Pokémon, since the word for rock, in Japanese, is Iwa (岩 Iwa).

Transportation

Rail

Iwate is served by the East Japan Railway Company (JR East) which operates two high-speed shinkansen lines in the prefecture and seven local rail lines. The Tōhoku Shinkansen has stations at Ichinoseki, Oshu, Kitakami, Hanamaki, Morioka, Iwate Town and Ninohe. The Akita Shinkansen starts at Morioka Station and connects to locations in Akita Prefecture.

JR East operates passenger and freight trains on the Tōhoku Main Line or Tōhoku-honsen in Iwate but sold the track north of Morioka to the Iwate Galaxy Railway Line in 2002. The two lines share track with JR still running freight trains and some passenger trains over IGR track and IGR running occasional passenger trains as far south as Hanamaki. There is a large JR freight yard and maintenance facility in Yahaba.

Local lines include the Ofunato Line, the Kitakami Line, the Kamaishi Line, the Tazawako Line, the Yamada Line and the Hanawa Line.

Other lines include the Sanriku Railway which operates two lines along the coast, the North Rias Line and the South Rias Line.

Road

Expressways

National highways

Air

Sea

- Ofunato Port

- Kamaishi Port

- Miyako Port

See also

Notes

- Frédéric, "Tōhoku" in Japan Encyclopedia, p. 970, at Google Books

- Frédéric, "Morioka" in Japan Encyclopedia, p. 661, at Google Books

- "【民話・昔話】鬼の手形". Bunka.pref.iwate.jp. Retrieved 7 June 2013.

- "Japanese Culture and Food: Iwate". Sapporo.co.uk. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- "A Story of Delicious Apples". Japanold.com. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- "言い伝えられた平泉". Iwate Prefectural Office. Archived from the original on 13 October 2013. Retrieved 7 June 2013.

- Frédéric, "Provinces and prefectures" in Japan Encyclopedia, p. 780, at Google Books, p. 780.

- 自然公園都道府県別面積総括 [General overview of area figures for Natural Parks by prefecture] (PDF) (in Japanese). Ministry of the Environment. 31 March 2019. Retrieved 17 August 2019.

- 自然公園の種類 [Types of Natural Parks] (in Japanese). Iwate Prefecture. Retrieved 17 August 2019.

- Schreiber, Mark, "Japan's food crisis goes beyond recent panic buying", The Japan Times, 17 April 2011, p. 9.

- Kyodo News, "Sea Shepherd's return to Iwate town enrages local fishermen", The Japan Times, 26 May 2011, p. 2.

- Iwate 1995-2020 population statistics

- Iwate 1920-2000 population statistics

- "27. Iwatesan" (PDF). Japan Meteorological Agency.

- "38-meter-high tsunami triggered by March 11 quake: survey". Kyodo News. Archived from the original on 6 April 2011. Retrieved 7 June 2013.

- Fukada, Takahiro (21 September 2011). "Iwate fisheries continue struggle to recover". The Japan Times. p. 3.

- Dennison, Kara. "Iwate Prefecture Adopts Geodude as Its Official Pokémon". Crunchyroll (in Portuguese). Retrieved 31 May 2019.

References

- Frédéric, Louis (2002 [1996]). Japan Encyclopedia. Translated by Käthe Roth. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01753-6, ISBN 978-0-674-01753-5. OCLC 58053128.

- Yiengpruksawan, Mimi Hall (1998). Hiraizumi: Buddhist Art and Regional Politics in Twelfth Century Japan. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674392051, ISBN 9780674392052. OCLC 38738867.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Iwate prefecture. |

- Iwate Prefecture Official Website (in Japanese)