Tax evasion

Tax evasion is the illegal evasion of taxes by individuals, corporations, and trusts. Tax evasion often entails taxpayers deliberately misrepresenting the true state of their affairs to the tax authorities to reduce their tax liability and includes dishonest tax reporting, such as declaring less income, profits or gains than the amounts actually earned, or overstating deductions.

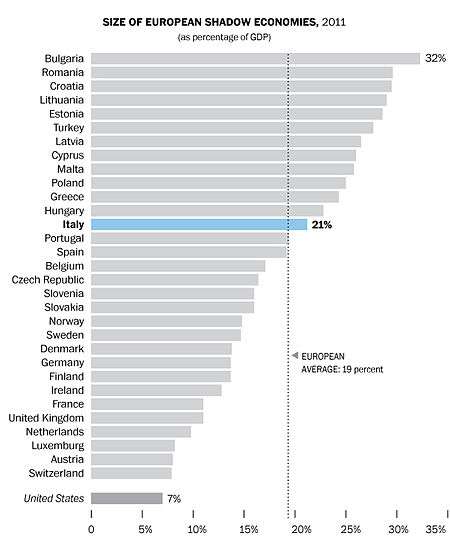

Tax evasion is an activity commonly associated with the informal economy.[1] One measure of the extent of tax evasion (the "tax gap") is the amount of unreported income, which is the difference between the amount of income that should be reported to the tax authorities and the actual amount reported.

In contrast, tax avoidance is the legal use of tax laws to reduce one's tax burden. Both tax evasion and avoidance can be viewed as forms of tax noncompliance, as they describe a range of activities that intend to subvert a state's tax system, although such classification of tax avoidance is not indisputable, given that avoidance is lawful, within self-creating systems.[2]

Economics

In 1968, Nobel laureate economist Gary Becker first theorized the economics of crime,[4] on the basis of which authors M.G. Allingham and A. Sandmo produced, in 1972, an economic model of tax evasion. This model deals with the evasion of income tax, the main source of tax revenue in developed countries. According to the authors, the level of evasion of income tax depends on the detection probability and the level of punishment provided by law.[5]

The literature's theoretical models are elegant in their effort to identify the variables likely to affect non-compliance. Alternative specifications, however, yield conflicting results concerning both the signs and magnitudes of variables believed to affect tax evasion. Empirical work is required to resolve the theoretical ambiguities. Income tax evasion appears to be positively influenced by the tax rate, the unemployment rate, the level of income and dissatisfaction with government.[6] The U.S. Tax Reform Act of 1986 appears to have reduced tax evasion in the United States.

In a 2017 study Alstadsæter et al. concluded based on random stratified audits and leaked data that occurrence of tax evasion rises sharply as amount of wealth rises and that the very richest are about 10 times more likely than average people to engage in tax evasion.[7]

Evasion of customs duty

Customs duties are an important source of revenue in developing countries. Importers attempt to evade customs duty by (a) under-invoicing and (b) misdeclaration of quantity and product-description. When there is ad valorem import duty, the tax base can be reduced through under-invoicing. Misdeclaration of quantity is more relevant for products with specific duty. Production description is changed to match a H. S. Code commensurate with a lower rate of duty.[8]

Smuggling

Smuggling is import or export of products by illegal means. Smuggling is resorted to for total evasion of customs duties, as well as for the import and export of contraband. Smugglers do not pay duty since the transport is covert, so no customs declaration is made.[8]

Evasion of value-added tax (VAT) and sales taxes

During the second half of the 20th century, value-added tax (VAT) emerged as a modern form of consumption tax throughout the world, with the notable exception of the United States. Producers who collect VAT from consumers may evade tax by under-reporting the amount of sales.[10] The US has no broad-based consumption tax at the federal level, and no state currently collects VAT; the overwhelming majority of states instead collect sales taxes. Canada uses both a VAT at the federal level (the Goods and Services Tax) and sales taxes at the provincial level; some provinces have a single tax combining both forms.

In addition, most jurisdictions which levy a VAT or sales tax also legally require their residents to report and pay the tax on items purchased in another jurisdiction. This means that consumers who purchase something in a lower-taxed or untaxed jurisdiction with the intention of avoiding VAT or sales tax in their home jurisdiction are technically breaking the law in most cases.

This is especially prevalent in federal countries like the US and Canada where sub-national jurisdictions charge varying rates of VAT or sales tax.

In liberal democracies, a fundamental problem with inhibiting evasion of local sales taxes is that liberal democracies, by their very nature, have few (if any) border controls between their internal jurisdictions. Therefore, it is not generally cost-effective to enforce tax collection on low-value goods carried in private vehicles from one jurisdiction to another with a different tax rate. However, sub-national governments will normally seek to collect sales tax on high-value items such as cars.[11]

Dennis Kozlowski is a particularly notable figure for his alleged evasion of sales tax. What started as an investigation into Kozlowski's failure to declare art purchases for the purpose of evading New York state sales taxes eventually led to Kozlowski's conviction and incarceration on more serious charges related to the misappropriation of funds during his tenure as CEO of Tyco International.

Government response

The level of evasion depends on a number of factors, including the amount of money a person or a corporation possesses. Efforts to evade income tax decline when the amounts involved are lower. The level of evasion also depends on the efficiency of the tax administration. Corruption by tax officials make it difficult to control evasion. Tax administrations use various means to reduce evasion and increase the level of enforcement: for example, privatization of tax enforcement[8] or tax farming.[12][13]

In 2011 HMRC, the UK tax collection agency, stated that it would continue to crack down on tax evasion, with the goal of collecting £18 billion in revenue before 2015.[14] In 2010, HMRC began a voluntary amnesty program that targeted middle-class professionals and raised £500 million.[15]

Corruption by tax officials

Corrupt tax officials co-operate with the taxpayers who intend to evade taxes. When they detect an instance of evasion, they refrain from reporting it in return for bribes. Corruption by tax officials is a serious problem for the tax administration in many less developed countries.

Level of evasion and punishment

Tax evasion is a crime in almost all developed countries, and the guilty party is liable to fines and/or imprisonment. In Switzerland, many acts that would amount to criminal tax evasion in other countries are treated as civil matters. Dishonestly misreporting income in a tax return is not necessarily considered a crime. Such matters are handled in the Swiss tax courts, not the criminal courts.

In Switzerland, however, some tax misconduct (such as the deliberate falsification of records) is criminal. Moreover, civil tax transgressions may give rise to penalties. It is often considered that the extent of evasion depends on the severity of punishment for evasion.

Privatization of tax enforcement

Professor Christopher Hood first suggested privatization of tax enforcement to control tax evasion more efficiently than a government department would.,[16] and some governments have adopted this approach. In Bangladesh, customs administration was partly privatized in 1991.[8]

Abuse by private tax collectors (see tax farming below) has on occasion led to revolutionary overthrow of governments who have outsourced tax administration.

Tax farming

Tax farming is an historical means of collection of revenue. Governments received a lump sum in advance from a private entity, which then collects and retains the revenue and bears the risk of evasion by the taxpayers. It has been suggested that tax farming may reduce tax evasion in less developed countries.[12]

This system may be liable to abuse by the "tax-farmers" seeking to make a profit, if they are not subject to political constraints. Abuses by tax farmers (together with a tax system that exempted the aristocracy) were a primary reason for the French Revolution that toppled Louis XVI.

PSI agencies

Pre-shipment inspection agencies like Société Générale De Surveillance S. A. and its subsidiary Cotecna are in business to prevent evasion of customs duty through under-invoicing and misdeclaration.

However, PSI agencies have cooperated with importers in evading customs duties. Bangladeshi authorities found Cotecna guilty of complicity with importers for evasion of customs duties on a huge scale.[17] In August 2005, Bangladesh had hired four PSI companies – Cotecna Inspection SA, SGS (Bangladesh) Limited, Bureau Veritas BIVAC (Bangladesh) Limited and INtertek Testing Limited – for three years to certify price, quality and quantity of imported goods. In March 2008, the Bangladeshi National Board of Revenue cancelled Cotecna's certificate for serious irregularities, while importers' complaints about the other three PSI companies mounted. Bangladesh planned to have its customs department train its officials in "WTO valuation, trade policy, ASYCUDA system, risk management" to take over the inspections.[18]

Cotecna was also found to have bribed Pakistan's prime minister Benazir Bhutto to secure a PSI contract by Pakistani importers. She and her husband were sentenced both in Pakistan and Switzerland.[19]

By continent

Europe

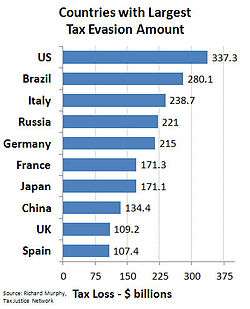

Germany, France, Italy, Denmark, Belgium

A network of banks, stock traders and top lawyers has obtained billions from the European treasuries through suspected fraud and speculation with dividend tax. The five hardest hit countries have lost together at least $62.9 billion.[20] Germany is the hardest hit country, with around €31 billion withdrawn from the German treasury.[21] Estimated losses for other countries include at least €17 billion for France, €4.5 billion in Italy, €1.7 billion in Denmark and €201 million for Belgium.[22][23][24]

Greece

Scandinavia

A paper by economists Annette Alstadsæter, Niels Johannesen and Gabriel Zucman, which used data from HSBC Switzerland (“Swiss leaks”) and Mossack Fonseca (“Panama Papers”), found that "on average about 3% of personal taxes are evaded in Scandinavia, but this figure rises to about 30% in the top 0.01% of the wealth distribution... Taking tax evasion into account increases the rise in inequality seen in tax data since the 1970s markedly, highlighting the need to move beyond tax data to capture income and wealth at the top, even in countries where tax compliance is generally high. We also find that after reducing tax evasion—by using tax amnesties—tax evaders do not legally avoid taxes more. This result suggests that fighting tax evasion can be an effective way to collect more tax revenue from the ultra-wealthy."[25]

United Kingdom

HMRC, the UK tax collection agency, estimated that in the tax year 2016–17, pure tax evasion (i.e. not including things like hidden economy or criminal activity) cost the government £5.3 billion. This compared to a wider tax gap (the difference between the amount of tax that should, in theory, be collected by HMRC, against what is actually collected) of £33 billion in the same year, an amount that represented 5.7% of liabilities. At the same time, tax avoidance was estimated at £1.7 billion (this does not include international tax arrangements that cannot be challenged under the UK law, including some forms of base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS)).[26]

In 2013, the Coalition government announced a crackdown on economic crime. It created a new criminal offence for aiding tax evasion and removed the requirement for tax investigation authorities to prove "intent to evade tax" to prosecute offenders.[27]

In 2015, Chancellor George Osborne promised to collect £5bn by "waging war" on tax evaders by announcing new powers for HMRC to target people with offshore bank accounts.[28] The number of people prosecuted for tax evasion doubled in 2014/15 from the year before to 1,258.[29]

United States

In the United States of America, Federal tax evasion is defined as the purposeful, illegal attempt to evade the assessment or the payment of a tax imposed by federal law. Conviction of tax evasion may result in fines and imprisonment.[30]

The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) has identified small businesses and sole proprietors as the largest contributors to the tax gap between what Americans owe in federal taxes and what the federal government receives. Small businesses and sole proprietorships contribute to the tax gap because there are few ways for the government to know about skimming or non-reporting of income without mounting significant investigations.

As of 2007 the most common means of tax evasion was overstatement of charitable contributions, particularly church donations.[31]

Estimates of lost government revenue

The IRS estimates that the 2001 tax gap was $345 billion and for 2006 it was $450 billion.[32] A study of the 2008 tax gap found a range of $450–$500 billion, and unreported income to be about $2 trillion, concluding that 18 to 19 percent of total reportable income was not being properly reported to the IRS.[6]

See also

- Global Forum on Transparency and Exchange of Information for Tax Purposes

- History of tax resistance

- Informal sector

- Land value tax

- Panama Papers

- Social inequality

- Tax amnesty

- Tax avoidance

- Tax haven

- Tax information exchange agreements

- Tax noncompliance

- Tax resistance

- Taxation as slavery

- Taxation as theft

- Unreported employment

- U.S. taxation of illegal income

Further reading

- Slemrod, Joel. 2019. "Tax Compliance and Enforcement." Journal of Economic Literature, 57 (4): 904-54.

References

- Tax Evasion & Whistleblowers: Curious Policy or Durable Strategy? Tax Law: International & Comparative Tax eJournal. SSRN. Accessed 5 May 2020.

- Michael Wenzel (2002). "The Impact of Outcome Orientation and Justice Concerns on Tax Compliance" (PDF). Journal of Applied Psychology: 4–5.

When taxpayers try to find loopholes with the intention to pay less tax, even if technically legal, their actions may be against the spirit of the law and in this sense considered noncompliant.

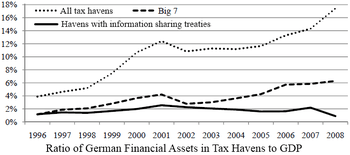

Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Hebous, Shafik (2011). "Money at the Docks of Tax Havens: A Guide". CESifo Working Paper Series. 70 (3587): 9. doi:10.1628/001522114X684547. hdl:10419/52472. SSRN 1934164.

- Gary Becker (1968). "Crime and Punishment: An Economic Approach" (PDF). The Journal of Political Economy. 76 (2): 169–217. doi:10.1086/259394.

- Allingham, M. G. and A. Sandmo [1972] ‘Income Tax evasion: A Theoretical Analysis’, Journal of Public Economics, Vol. 1, 1972, pp. 323–38.

- Cebula, Richard; Feige, Edgar L. (n.d.). "America's Underground Economy: Measuring the Size, Growth and Determinants of Income Tax Evasion in the U.S". Ideas.repec.org. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Alstadsæter et al. 2017. Tax Evasion and Inequality∗

- Chowdhury, F. L. (1992) Evasion of Customs Duty in Bangladesh, unpublished MBA dissertation, Graduate School of Management, Monash University, Australia.

- David Cay Johnston (13 December 2011). "Where's the fraud, Mr. President?". Reuters.

- Spiro, Peter S. (2005), "Tax Policy and the Underground Economy," in Christopher Bajada and Friedrich Schneider, eds., Size, Causes and Consequences of the Underground Economy (Ashgate Publishing).

- Tomášková, Eva (2008). "Tax Evasion in the Czech Republic – In: A Brief Introduction to Czech Law. Rincon: The American Institute for Central European Legal Studies (AICELS) 2008. pp. 111–21 ISBN 978-0-692-00045-8" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 3, 2011.

- Stella, Peter (1993). "Tax Farming: A Radical Solution for Developing Country Tax Problems?". IMF Staff Papers. 40 (1): 217–25. doi:10.2307/3867383. JSTOR 3867383.

- Alam. D (1999) Introduction of PSI system in Bangladesh: Facts and Documents, Desh Prokashon, Dhaka.

- "Watch out, the taxman's about: HMRC ordered to bring in £18bn in government crackdown". Mail Online. London: dailymail.co.uk. March 17, 2011. Retrieved August 12, 2011.

- Russell, Jonathan (June 10, 2011). "HMRC opens 16 criminal cases over tax evasion". The Telegraph. London: telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved August 12, 2011.

- Hood, C. (1986) Privatizing UK tax Law Enforcement?, Public Administration, Vol. 64, Autumn, 1986, p. 319–33.

- "NBR showcauses Cotecna on car import scam". New Age. Dhaka: Media New Age Ltd. 14 September 2007. Archived from the original on November 20, 2010.

- "PSI system likely to continue". Bangladesh News. 3 May 2008. Archived from the original on May 11, 2008. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- Langley, Alison (6 August 2003). "Pakistan: Bhutto Sentenced In Switzerland". New York Times.

- "CORRECTIV - Investigative. Independent. Non-profit". cumex-files.com. Retrieved 2018-11-09.

- Hill, Jenny (2017-06-09). "Germany fears huge losses in massive tax scandal". BBC News. Retrieved 2018-11-09.

- "Kuppet mod Europa". DR (in Danish). Retrieved 2018-11-09.

- Vartdal, Ragnhild. "Norge rammet av europeisk skatteskandale" [Norway affected by European tax scandal]. NRK (in Norwegian Bokmål). Retrieved 2018-11-09.

- magazine, Le Point (2018-10-18). ""CumEx Files " : la fraude fiscale à 55 milliards d'euros" ["CumEx Files": tax fraud at 55 billion euros]. Le Point (in French). Retrieved 2018-11-09.

- Alstadsæter, Annette; Johannesen, Niels; Zucman, Gabriel (23 October 2018). "Tax Evasion and Inequality" (PDF). gabriel-zucman.eu.

- "Measuring tax gaps 2018 edition" (PDF). HM Revenue & Customs. 14 June 2018.

- "UK government announces corporate tax evasion clampdown". BBC News. 19 March 2015.

- "George Osborne wages war on tax evasion and avoidance". Channel 4 News. 19 March 2015.

- Ames, Jonathan; Gibb, Frances (14 December 2015). "Lawyers and tradesmen caught in tax clampdown".

- 26 U.S.C. § 7201.

- Sabatini, Patricia (25 March 2007). "Tax Cheats Cost U.S. hundreds of billions". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

- "Tax Gap for Tax Year 2006 Overview Jan. 6, 2012" (PDF). U.S. Internal Revenue Service. Retrieved 2012-06-14.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tax evasion. |

- Tax Evasion and Fraud collected news and commentary at The Economist

- "Tax Evasion collected news and commentary". The New York Times.

- Employment Tax Evasion Schemes common employment schemes at IRS

- United States

- US Justice Dept press release on Jeffrey Chernick, UBS tax evader

- US Justice Tax Division and its enforcement efforts