Yerba mate

Yerba mate or yerba-maté[1] (Ilex paraguariensis), from Spanish [ˈʝeɾβa ˈmate]; Portuguese: erva-mate, [ˈɛɾvɐ ˈmate] or [ˈɛɾvɐ ˈmatʃɪ]; Guarani: ka'a, IPA: [kaʔa], is a plant species of the holly genus Ilex native to South America.[2] It was named by the French botanist Augustin Saint-Hilaire.[3]

| Yerba mate | |

|---|---|

| |

| Ilex paraguariensis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Asterids |

| Order: | Aquifoliales |

| Family: | Aquifoliaceae |

| Genus: | Ilex |

| Species: | I. paraguariensis |

| Binomial name | |

| Ilex paraguariensis | |

The indigenous Guaraní and some Tupí communities in southern Brazil first cultivated and used yerba mate prior to European colonization of the Americas. The leaves of the plant are steeped in hot water to make a beverage known as mate. When served cold, it is called tereré in the Guarani language. Both the plant and the beverage contain caffeine.

Mate is traditionally consumed in central and southern regions of South America, primarily in Paraguay, as well as in Argentina, Uruguay, southern and central-western Brazil, the Gran Chaco of Bolivia, and southern Chile.[4] It has also become popular in the Druze community in the Levant, especially in Syria and Lebanon, where it is imported from Argentina, thanks to 19th-century Syrian immigrants from Argentina.[5] Yerba mate can now be found worldwide in various energy drinks as well as being sold as a bottled or canned iced tea.

Name and pronunciation

The name given to the plant in the Guaraní, language of the indigenous people who first used mate, is ka'a, which has the same meaning as "herb". Congonha, in Portuguese, is derived from the Tupi expression, meaning something like "what keeps us alive", but a term rarely used nowadays. Mate is from the Quechua mati,[6] a word that means "container for a drink" and "infusion of an herb", as well as "gourd".[7] The word mate is used in modern Portuguese and Spanish.

The pronunciation of yerba mate in Spanish is [ˈʃeɾβa ˈmate].[6] The accent on the word mate is on the first syllable.[6] The word hierba is Spanish for "herb", where the initial "h" is silent; yerba is a variant spelling of hierba used throughout Latin America.[8] Yerba may be understood as "herb" but also as "grass" or "weed". In Argentina, yerba refers exclusively to the yerba mate plant.[8] Yerba mate, therefore, originally translated literally as the "gourd herb", i.e. the herb one drinks from a gourd.

The (Brazilian) Portuguese name for the plant is either erva-mate [ˈɛʁvɐ ˈmätʃi], pronounced variously as [ˈɛɾvɐ ˈmäte], [ˈɛɾvə ˈmätɪ] or [ˈɛɻvɐ ˈmätʃɪ] in the regions of traditional consumption, [ˈæə̯ʀvə ˈmäˑtɕ] in coastal, urban Rio de Janeiro, the most used term..[9] The drinks it is used to prepare are chimarrão (hot), tereré (cold), or chá mate (hot or cold). While chá mate is made with toasted leaves, the other drinks are made with raw,green leaves, and are very popular in the south and center-west of the country. Most people colloquially address both the plant and the beverage by the word mate.[10]

In English, both the spellings "mate" and "maté" are used to refer to the plant or beverage, but the latter spelling is incorrect in both Spanish and Portuguese, as it would put the stress on the second syllable, while the word is correctly pronounced with the stress on the first syllable. The addition of the acute accent over the final "e" in the English spelling was likely added as a hypercorrection to indicate that the final "-é" is not silent.[11][12] Indeed, the word maté in Spanish has a completely different meaning;[13] in Spanish: maté is understood as being the first person past tense conjugation of matar ("to kill") and means "I killed".[14]

There are no variations in spelling of mate (the plant) in Spanish.[6] In both Spanish and Portuguese, the first syllable of mate (plant) is the tonic one, and the word does not require a written accent. If the tonic syllable were the last one, the accent would be required, as maté.

Description

Ilex paraguariensis begins as a shrub and then matures to a tree, growing up to 15 metres (49 ft) tall. The leaves are evergreen, 7–110 millimetres (0.3–4.3 in) long and 30–55 millimetres (1.2–2.2 in) wide, with serrated margins. The leaves are often called yerba (Spanish) or erva (Portuguese), both of which mean "herb". They contain caffeine (known in some parts of the world as mateine) and related xanthine alkaloids, and are harvested commercially.

The flowers are small and greenish-white with four petals. The fruit is a red drupe 4–6 millimetres (0.16–0.24 in) in diameter.

History

Mate was first consumed by the indigenous Guaraní people and also spread in the Tupí people that lived in southern Brazil and Paraguay. Its consumption became widespread during European colonization, particularly in the Spanish colony of Paraguay in the late 16th century, among both Spanish settlers and indigenous Guaraní, who had, to some extent before the Spanish arrival, consumed it. Mate consumption spread in the 17th century to the River Plate and from there to Argentina, Chile, Bolivia, and Peru. This widespread consumption turned it into Paraguay's main commodity above other wares, such as tobacco, and the labour of indigenous peoples was used to harvest wild stands.

In the mid-17th century, Jesuits managed to domesticate the plant and establish plantations in their Indian reductions in Misiones, Argentina, sparking severe competition with the Paraguayan harvesters of wild stands. After their expulsion in the 1770s, their plantations fell into decay, as did their domestication secrets. The industry continued to be of prime importance for the Paraguayan economy after independence, but development in benefit of the Paraguayan state halted after the War of the Triple Alliance (1864–1870) that devastated the country both economically and demographically. Some regions with mate plantations in Paraguay became Argentine territory.

Brazil then became the largest producer of mate.[15] In Brazilian and Argentine projects in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the plant was domesticated once again, opening the way for plantation systems. When Brazilian entrepreneurs turned their attention to coffee in the 1930s, Argentina, which had long been the prime consumer,[16] took over as the largest producer, resurrecting the economy in Misiones Province, where the Jesuits had once had most of their plantations. For years, the status of largest producer shifted between Brazil and Argentina.[16] Today, Brazil is the largest producer, with 53%, followed by Argentina, 37%, and Paraguay, 10%.[17][18]

In the city of Campo Largo, state of Paraná, Brazil, there is a Mate Historic Park (Portuguese: Parque Histórico do Mate), funded by the state government to educate people on the sustainable harvesting methods needed to maintain the integrity and vitality of the oldest wild forests of mate in the world. As of June 2014, however, the park is closed to public visitation.[19]

Cultivation

The yerba mate plant is grown and processed in its native regions of South America, specifically in northern Argentina (Corrientes and Misiones), Paraguay, Uruguay, and southern Brazil (Rio Grande do Sul, Santa Catarina, Paraná, and Mato Grosso do Sul). Cultivators are known as yerbateros (Spanish) or ervateiros (Brazilian Portuguese).

Seeds used to germinate new plants are harvested after they have turned dark purple, typically from January to April. After harvest, they are submerged in water in order to eliminate floating non-viable seeds and detritus like twigs, leaves, etc. New plants are started between March and May. For plants established in pots, transplanting takes place April through September. Plants with bare roots are transplanted only during the months of June and July.[20]

Many of the natural enemies of yerba mate are difficult to control in plantation settings. Insect pests include Gyropsylla spegazziniana, a true bug that lays eggs in the branches; Hedyphates betulinus, a type of beetle that weakens the tree and makes it more susceptible to mold and mildew; Perigonia lusca, a moth whose larvae eat the leaves; and several species of mites.[20]

When I. paraguariensis is harvested, the branches are often dried by a wood fire, imparting a smoky flavor. The strength of the flavor, caffeine levels, and other nutrients can vary depending on whether it is a male or female plant. Female plants tend to be milder in flavor and lower in caffeine. They are also relatively scarce in the areas where yerba mate is planted and cultivated.[21]

According to FAO in 2012, Brazil is the biggest producer of mate in the world with 513,256 MT (58%), followed by Argentina with 290,000 MT (32%) and Paraguay with 85,490 MT (10%).[17]

Use as a beverage

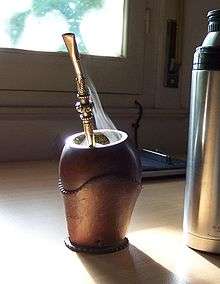

The infusion, called mate in Spanish-speaking countries or chimarrão in Brazil, is prepared by filling a container, traditionally a small, hollowed-out gourd, up to three-quarters full with dry leaves (and twigs) of I. paraguariensis, and filling it up with water at a temperature of 70–80 °C (158–176 °F), hot but not boiling. Sugar may or may not be added. The infusion may also be prepared with cold water, in which case it is known as tereré.[22]

Drinking mate is a common social practice in Paraguay, Uruguay, Argentina, Chile, and southern Brazil among people of all ages, and is often a communal ritual following customary rules. Friends and family members share from the same container, traditionally a hollow gourd (also called a guampa, porongo, or simply mate in Spanish, a cabaça or cuia in Portuguese, or a zucca in Italian), and drink through the same wooden or metal straw (a bombilla in Spanish or bomba in Portuguese). The gourd is given by the brewer to each person, often in a circle, in turn; the recipient gives thanks, drinks the few mouthfuls in the container, and then returns the mate to the brewer, who refills it and passes it to the next person in clockwise order. Although traditionally made from a hollowed calabash gourd, these days mate "gourds" are produced from a variety of materials including wood, glass, bull horns, ceramic, and silicone.[23]

In the same way as people meet for tea or coffee, friends often gather and drink mate (matear) in Paraguay, Argentina, southern Brazil, and Uruguay. In warm weather the hot water is sometimes replaced by lemonade. Paraguayans typically drink yerba mate with cold water during hot days and hot water in the morning and during cooler temperatures.

Yerba mate is most popular in Paraguay and Uruguay, where people are seen walking the streets carrying the mate and often a termo (thermal vacuum flask) in their arms. In Argentina, 5 kg (11 lb) of yerba mate is consumed annually per capita; in Uruguay, the largest consumer, consumption is 10 kg (22 lb).[24] The amount of herb used to prepare the infusion is much greater than that used for tea and other beverages, which accounts for the large weights.

The flavor of brewed mate resembles an infusion of vegetables, herbs, and grass and is reminiscent of some varieties of green tea. Some consider the flavor to be very agreeable, but it is generally bitter if steeped in hot water. Sweetened and flavored mate is also sold, in which the mate leaves are blended with other herbs (such as peppermint) or citrus rind.[25]

In Paraguay, Brazil, and Argentina, a version of mate known as mate cocido (or just mate or cocido) in Paraguay and chá mate in Brazil is sold in teabags and in a loose leaf form. It is often served sweetened in specialized shops or on the street, either hot or iced, pure or with fruit juice (especially lime, known in Brazil as limão) or milk. In Paraguay, Argentina, and southern Brazil, this is commonly consumed for breakfast or in a café for afternoon tea, often with a selection of sweet pastries (facturas).

An iced, sweetened version of mate cocido is sold as an uncarbonated soft drink, with or without fruit flavoring. In Brazil, this cold version of chá mate is especially popular in the south and southeast regions, and can easily be found in retail stores in the same cooler as other soft drinks.[10] Mate batido, which is toasted, has less of a bitter flavor and more of a spicy fragrance. Mate batido becomes creamy when shaken and is more popular in the coastal cities of Brazil, as opposed to the far southern states, where it is more commonly consumed in the traditional way (green, with a silver straw from a shared gourd), and called chimarrão (cimarrón in Spanish, particularly Argentine Spanish).[26]

In Paraguay, western Brazil (Mato Grosso do Sul, west of São Paulo and Paraná), and the Argentine littoral, a mate infusion, called tereré in Spanish and Portuguese or tererê in Portuguese in southern Brazil, is also consumed as a cold or iced beverage, usually sucked out of a horn cup called a guampa with a bombilla. Tereré can be prepared with cold water (the most common way in Paraguay and Brazil) or fruit juice (the most common way in Argentina). The version with water is more bitter; fruit juice acts as a sweetener (in Brazil, this is usually avoided with the addition of table sugar). Medicinal or culinary herbs, known as yuyos (weeds), may be crushed with a pestle and mortar and added to the water for taste or medicinal reasons.[27]

Paraguayans have a tradition of mixing mate with crushed leaves, stems, and flowers of the plant known as flor de agosto[28] (the flower of August, plants of the genus Senecio, particularly Senecio grisebachii), which contain pyrrolizidine alkaloids. Modifying mate in this fashion is potentially toxic, as these alkaloids can cause veno-occlusive disease, a rare condition of the liver which results in liver failure due to progressive occlusion of the small venous channels.[29]

Mate has also become popular outside of South America. In the tiny hamlet of Groot Marico, North West Province, South Africa, mate was introduced to the local tourism office by the returning descendants of the Boers, who in 1902 had emigrated to Patagonia in Argentina after losing the Anglo Boer War. It is also commonly consumed in Lebanon, Syria, and some other parts of the Middle East, mainly by Druze and Alawite people. Most of its popularity outside South America is a result of historical emigration to South America and subsequent return. It is consumed worldwide by expatriates from the Southern Cone.[30][31]

Use as a health food

Mate is often consumed as a health food. Packages of yerba mate are available in health food stores and are frequently stocked in large supermarkets in Europe, Australia, and the United States. By 2013, Asian interest in the drink had seen significant growth that led to significant exports to those countries.[32]

Chemical composition and properties

Yerba mate contains a variety of polyphenols such as the flavonoids quercetin and rutin.[33]

Yerba mate contains three xanthines: caffeine, theobromine, and theophylline, the main one being caffeine. Caffeine content varies between 0.7% and 1.7% of dry weight[34] (compared with 0.4–9.3% for tea leaves, 2.5–7.6% in guarana, and up to 3.2% for ground coffee);[35] theobromine content varies from 0.3% to 0.9%; theophylline is typically present only in small quantities or sometimes completely absent.[36] A substance previously called "mateine" is a synonym for caffeine (like theine and guaranine).

Yerba mate also contains elements such as potassium, magnesium, and manganese.[37]

Health effects

Yerba mate has been claimed to have various effects on human health, most of which have been attributed to the high quantity of polyphenols found in the beverage.[33] Research has found that yerba mate may improve allergy symptoms[38] and reduce the risk of diabetes mellitus and high blood sugar in mice.[39]

Mate also contains compounds that may act as an appetite suppressant and possible weight loss tool,[40] increases mental energy and focus,[41] improves mood,[42][43] and promotes deeper sleep; however, sleep may be negatively affected in people who are sensitive to caffeine.[41]

Before 2011, there were no double-blind, randomized prospective clinical trials of yerba mate consumption with respect to chronic disease.[44] Many studies have been conducted since then, pointing to at least some probable health benefits of yerba mate, such as reduction of fat cells, inflammation, and cholesterol, although more research is needed.[43] Some non-blinded studies have found mate consumption to be effective in lipid lowering.[44] Another study determined that mate reduces progression of arteriosclerosis in rabbits but did not decrease serum cholesterol or aortic TBARS and antioxidant enzymes.[45]

Weight loss

Yerba mate contains polyphenols such as flavonoids and phenolic acids, which work by inhibiting enzymes like pancreatic lipase[46] and lipoprotein lipase, which in turn play a role in fat metabolism. Yerba mate has been shown to increase satiety by slowing gastric emptying. Effects on weight loss may be due to reduced absorption of dietary fats and/or altered cholesterol metabolism.[43]

Despite yerba mate's potential for reducing body weight, there is minimal data on the effects of yerba mate on body weight in humans.[47] Therefore, yerba mate should not be recommended over diet and physical exercise[48] without further study on its effects.

Cancer

The consumption of hot mate tea is associated with oral cancer,[49] esophageal cancer,[50] cancer of the larynx,[50] and squamous cell cancers of the head and neck.[51][52] Studies show a correlation between tea temperature and likelihood of cancer, making it unclear how much of a role mate itself plays as a carcinogen.[50]

E-NTPDase activity

Research also shows that mate preparations can alter the concentration of members of the ecto-nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase (E-NTPDase) family, resulting in elevated levels of extracellular ATP, ADP, and AMP. This was found with chronic ingestion (15 days) of an aqueous mate extract, and may lead to a novel mechanism for manipulation of vascular regenerative factors, i.e. treating heart disease.

Antioxidants

In an investigation of mate antioxidant activity, there was a correlation found between content of caffeoyl-derivatives and antioxidant capacity (AOC). Amongst a group of Ilex species, the antioxidant activity of Ilex paraguariensis was the highest.

Monoamine oxidase inhibition activity

A study from the University of São Paulo cites yerba mate extract as an inhibitor of MAO activity; the maximal inhibition observed in vitro was 40–50%. A monoamine oxidase inhibitor is a type of antidepressant, so there is some data to suggest that yerba mate has a calming effect in this regard.[53]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ilex paraguariensis. |

- Black drink

- Club-Mate

- Matte Leão

- Ilex guayusa, known as guayusa, another caffeine-containing holly species of the Ilex genus, native to the Ecuadorian Amazon rainforest

- Ilex vomitoria, a caffeine-containing species of the Ilex genus native to North America

- Kuding, Ilex kudingcha

- Materva, a mate soft drink

- Nativa

- Guayaki, a brand of drinks based out of California

References

- "yerba". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

"yerba". Lexico UK Dictionary. Oxford University Press.

"yerba maté". Merriam-Webster Dictionary.

"yerba maté". CollinsDictionary.com. HarperCollins.

"yerba maté". Dictionary.com Unabridged. Random House. - "ITIS Report". itis.gov. Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- "Index of Botanists". harvard.edu. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

- World Conservation Monitoring Centre (1998). "Ilex paraguariensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 1998: e.T32982A9740718. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.1998.RLTS.T32982A9740718.en.

- "Argentina's 'yerba mate' crunch". globalpost.com. Retrieved 30 April 2015.

- Real Academia Española. "Mate". Retrieved 23 May 2013

- AULEX, "Online Quechua-Spanish Dictionary". Retrieved 23 May 2013

- Real Academia Española. "Yerba". Retrieved 23 May 2013

- FERREIRA, A. B. H. Novo Dicionário da Língua Portuguesa. Segunda edição. Rio de Janeiro: Nova Fronteira, 1986. p.453

- "Mate: o chá da hora". Retrieved 4 September 2012.

- "Merriam-Webster's Online Dictionary". M-w.com. 13 August 2010. Retrieved 5 June 2011.

- "mate - beverage". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- . YMAA http://www.yerbamateassociation.org/index.php. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "Word Magic Spanish Dictionary". Retrieved 23 May 2013

- "Erva-mate - o ouro verde do Paraná". Retrieved 10 July 2013

- "History of Mate". Establecimiento Las Marías. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- "FAOSTAT". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

- List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor

- "Parque Histórico do Mate" [Mate Historic Park] (in Portuguese). Paraná State Secretariat for Culture. Retrieved 3 June 2014.

- Burtnik, Oscar José, "Yerba Mate Production", 3rd Edition, 2006. Retrieved 24 May 2013

- "Nativa Yerba Mate". Native Yerba Mate. Retrieved 18 July 2011.

- How to make mate (in Spanish)

- Guide to Yerba Mate Gourds

- "Mate: The Bitter Tea South Americans Love to Drink". Retrieved 30 May 2013

- "Flavored Yerba Mate". Ma Tea. Retrieved 30 May 2013.

- "Significado de 'cimarrón'". Retrieved 5 July 2013.

- "Terere". Ma Tea. Retrieved 30 May 2013.

- "Flor de agosto".

- McGee, J; Patrick, R S; Wood, C B; Blumgart, L H (1976). "A case of veno-occlusive disease of the liver in Britain associated with herbal tea consumption". Journal of Clinical Pathology. 29 (9): 788–94. doi:10.1136/jcp.29.9.788. PMC 476180. PMID 977780.

- Folch, C. (2009). "Stimulating Consumption: Yerba Mate Myths, Markets, and Meanings from Conquest to Present". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 52: 6–36. doi:10.1017/S0010417509990314.

- ""Mate" tea a long-time Lebanese hit". Your Middle East. Retrieved 6 January 2017.

- "La yerba mate sigue ganando adeptos en países asiáticos". Territorio Digital (Argentina). 24 January 2013. Retrieved 24 January 2013.

- Gambero A, Ribeiro ML (January 2015). "The positive effects of yerba maté (Ilex paraguariensis) in obesity". Nutrients. 7 (2): 730–50. doi:10.3390/nu7020730. PMC 4344557. PMID 25621503.

- Dellacassa, Cesio et al. Departamento de Farmacognosia, Facultad de Química, Universidad de la República, Uruguay, Noviembre: 2007, pages 1–15

- "Activities of a Specific Chemical Query". Ars-grin.gov. Retrieved 5 June 2011.

- Vázquez, A; Moyna, P (1986). "Studies on mate drinking". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 18 (3): 267–72. doi:10.1016/0378-8741(86)90005-x. PMID 3821141.

- Valduga, Eunice; de Freitas, Renato João Sossela; Reissmann, Carlos B.; Nakashima, Tomoe (1997). "Caracterização química da folha de Ilex paraguariensis St. Hil. (erva-mate) e de outras espécies utilizadas na adulteração do mate". Boletim do Centro de Pesquisa de Processamento de Alimentos (in Portuguese). 15 (1): 25–36. doi:10.5380/cep.v15i1.14033.

- Bremner, Paul; Heinrich, Michael (2010). "Natural products as targeted modulators of the nuclear factor-KB pathway". Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology. 54 (4): 453–472. doi:10.1211/0022357021778637. PMID 11999122.

- Bracesco N, Sanchez AG, Contreras V, Menini T, Gugliucci A (July 2011). "Recent advances on Ilex paraguariensis research: minireview". J Ethnopharmacol. 136 (3): 378–84. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2010.06.032. PMID 20599603.

- Wichtl, Max, ed. (2004). Herbal Drugs and Phytopharmaceuticals. Medpharm. ISBN 978-0849319617.

- Sanz, Tenorio; Isasa, Torija (1991). "Mineral elements in mate herb (Ilex paraguariensis St. H.)". Arch Latinoam Nutr. 41 (3): 441–454. PMID 1824521.

- Klein, Siegrid; Rister, Robert (1998). The Complete German Commission E Monographs: Therapeutic Guide to Herbal Medicines. The American Botanical Council. ISBN 978-0965555500.

- Petre, Alina (2016). "8 Health Benefits of Yerba Mate (Backed by Science)". authoritynutrition.com. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- Bracesco, N.; Sanchez, A.G.; Contreras, V.; Menini, T.; Gugliucci, A. (2011). "Recent advances on Ilex paraguariensis research: Minireview". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 136 (3): 378–84. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2010.06.032. PMID 20599603.

- Mosimann, AL; Wilhelm-Filho, D; da Silva, EL (2006). "Aqueous extract of Ilex paraguariensis attenuates the progression of atherosclerosis in cholesterol-fed rabbits". BioFactors. 26 (1): 59–70. doi:10.1002/biof.5520260106. PMID 16614483.

- de la Garza AL, Milagro FI, Boque N, Campión J, Martínez JA (May 2011). "Natural inhibitors of pancreatic lipase as new players in obesity treatment". Planta Medica. 77 (8): 773–85. doi:10.1055/s-0030-1270924. PMID 21412692.

- Pittler MH, Schmidt K, Ernst E (May 2005). "Adverse events of herbal food supplements for body weight reduction: systematic review". Obes Rev. 6 (2): 93–111. doi:10.1111/j.1467-789X.2005.00169.x. PMID 15836459.

- Pittler MH, Ernst E (April 2004). "Dietary supplements for body-weight reduction: a systematic review". Am J Clin Nutr. 79 (4): 529–36. doi:10.1093/ajcn/79.4.529. PMID 15051593.

- Dasanayake, Ananda P.; Silverman, Amanda J.; Warnakulasuriya, Saman (2010). "Maté drinking and oral and oro-pharyngeal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Oral Oncology. 46 (2): 82–86. doi:10.1016/j.oraloncology.2009.07.006. PMID 20036605.

- Loria, Dora; Barrios, Enrique; Zanetti, Roberto (2009). "Cancer and yerba mate consumption: A review of possible associations". Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública. 25 (6): 530–9. doi:10.1590/S1020-49892009000600010. PMID 19695149.

- Goldenberg, D; Lee, J; Koch, W; Kim, M; Trink, B; Sidransky, D; Moon, C (2004). "Habitual risk factors for head and neck cancer". Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 131 (6): 986–93. doi:10.1016/j.otohns.2004.02.035. PMID 15577802.

- Goldenberg, David; Golz, Avishay; Joachims, Henry Zvi (2003). "The beverage maté: A risk factor for cancer of the head and neck". Head & Neck. 25 (7): 595–601. doi:10.1002/hed.10288. PMID 12808663.

- http://www.globalsciencebooks.info/Online/GSBOnline/images/0706/MAPSB_1(1)/MAPSB_1(1)37-46o.pdf (Page 43)