Economic ethics

Economic ethics combines economics and ethics, uniting value judgements from both disciplines in order to predict, analyse and model economic phenomena. It encompasses the theoretical ethical prerequisites and foundations of economic systems. The school of thought dates back to the Greek philosopher Aristotle, whose Nicomachean Ethics describes the connection between objective economic principle and the consideration of justice.[1] The academic literature on economic ethics is extensive, citing such authority as natural law and religious law as influences to normative rules in economics.[2] The consideration of moral philosophy, or the idea of a moral economy, for example, is a point of departure in assessing behavioural economic models.[3] Ethics presents a trilemma for economics, namely in standard creation, standard application, and who the beneficiaries of good, by these standards, should be.[4] This, in conjunction with the fundamental assumption of rationality in economics, creates the link between itself and ethics as it is ethics which, in part, studies the concepts of right and wrong.[4]

| Part of a series on |

| Economics |

|---|

|

|

|

By application |

|

Notable economists |

|

Lists |

|

Glossary |

|

| Part of a series on |

| Philosophy |

|---|

|

| Branches |

| Periods |

|

| Traditions |

|

Traditions by region Traditions by school Traditions by religion |

| Literature |

|

| Philosophers |

| Lists |

| Miscellaneous |

|

|

History

Ancient economic thought

Ancient Indian economic thought centred on the relationship between the concepts of happiness, ethics and economic values, with the connections between them constituting their description of human existence.[5] The Upanishads' fundamental idea of transcendental unity, oneness and stability is a deduction of this relationship.[6] Ancient Indian philosophy and metaphysics indicates an understanding of several modern economic concepts. For example, their regulation of demand when it exceeded supply as a means of avoiding anarchy, achieved at the time by stressing that non-material goods was the source of happiness, is a reflection of Marshall’s dictum of the insatiability of wants.[5] The Rig Veda illustrates an apprehension of economic inequality per Chapter X, 117, 1-6 which states that, 'The riches of the liberal never waste away, while he who will not give finds no comfort in them,’ indicating that generating personal wealth wasn't considered immoral although keeping this wealth to one's self is a sin.[5] The Arthasastra formulated laws that promote economic efficiency in the context of an ethical society. The author, Kautilya, posits that building infrastructure is a key determinant of economic growth when constructed in an ethical environment, which is the responsibility of the king.

Ancient Greek philosophers often combined economic teachings with ethical systems. Socrates, Plato and Aristotle subscribed to the idea that happiness is the most valuable good humans can strive for.[5] The belief that happiness couldn't be achieved without pleasure posed complications to the relationship between ethics and economics at the time. Callicles, for example, held that one who lives rightly should gratify all their desires by way of their courage and practicality which presented an anomaly for the issue of scarcity and the regulation of consumption as a result.[5] This was reconciled by the division of labour, where basic human wants such as food, clothing and shelter, were efficiently manufactured given each individual limits their production to their most productive function, thus maximising utility.[7] Xenophon's Oeconomicus, inspired by Socrates' concept of eudaimonia, necessitates that since virtue is knowledge one should understand how to use money and property well rather than merely acquire it for personal gain.[8]

Middle Ages

Religion was at the core of economic life during the Middle Ages, and hence the theologians of the time used inference from their respective ethical teachings to answer economic questions and achieve economic objectives.[9] This was the approach also adopted by philosophers during the Age of Enlightenment.[9] The Roman Catholic Church altered its doctrinal interpretation of the validity of a marriage in order to, amongst alternate motivations, prevent competition from threatening its monopolistic market position.[10] Usury was seen as an ethical issue in the Church, with justice having added value in comparison to economic efficiency.[10] The transition from an agrarian lifestyle to money-based commerce in Israel led to the adoption of interest in lending and borrowing given it was not directly prohibited in the Torah, under the ideal 'that your brother may live with you.'[11] Economic development in the Middle Ages was contingent on the ethical practices of merchants,[12] founded by the transformation in how medieval society understood the economics of property and ownership.[13] Islam supported this anti-ascetic ethic in the role of merchants, given its teaching that salvation derives from moderation rather than abstinence in such affairs.[14]

Classical economics

.png)

The Labour Theory of Value holds that labour is the source of all economic value, which was the viewpoint of David Ricardo, Adam Smith and other classical economists.[15] The distinction between 'wage-slaves' and 'proper slaves' in this theory, with both being viewed as commodities, is founded on moral principle given that 'wage-slaves' voluntarily offer their privately owned labour-power to a buyer for a bargained price, while 'proper slaves', according to Karl Marx, have no such rights.[15] Mercantilism, although advocated by classical economics, is regarded as ethically ambiguous in academic literature. Adam Smith noted that the national economic policy favoured the interests of producers at the expense of consumers given that domestically produced goods were subject to high inflation.[16] The competition between domestic households and foreign speculators also led to unfavourable balance of trades, i.e. increasing current account deficits on the balance of payments.[17] Writers and commentators of the time employed Aristotle's ethical counsel in order to solve this economic dilemma.[17]

Neoclassical economics

The moral philosophy of Adam Smith founded the neoclassical worldview in economics that one's quest for happiness is the ultimate purpose of life and that the concept of homo oeconomicus describes the fundamental behaviour of the economic agent.[18][19] Such an assumption as that individuals are self-interested and rational has implied the exemption of collective ethics.[18] Under rational choice and neoclassical economics' adoption of Newtonian atomism, many consumer behaviours are disregarded, meaning that it often cannot explain the source of consumer preferences when not constrained by the individual.[20] The role of collective ethics in consumer preference cannot be explained by neoclassical economics.[21] This degrades the applicability of the market demand function, its key analytical tool, to real economic phenomena as a result.[20] In principle, economists thus avoided, and continue to avoid, the assumptions of economic models from abstracting the unique aspects of economic problems.[22]

Contemporary history

According to John Maynard Keynes, the complete integration of ethics and economics is contingent on the rate of economic development.[23] Economists have been able to aggregate the preferences of agents, under the assumption of homo oeconomicus, via the merging of utilitarian ethics and institutionalism.[21] Keynes departed from the atomistic view of neoclassical economics with his totalistic perspective of the global economy, given that, 'the whole is not equal to the sum of its parts....the assumptions of a uniform and homogeneous continuum are not satisfied.' [24] This enforced the idea that an unethical socioeconomic state is apparent when the economy is under full employment, to which Keynes proposed productive spending as a mechanism to return the economy to full employment; the state where, also, an ethically rational society exists.[21]

Influences

Religion

Philosophers in the Hellenistic tradition became a driving force to the Gnostic vision, redemption of the spirit through asceticism, that has founded the debate regarding evil and ignorance in policy discussions.[1] The amalgamation of ancient Greek philosophy, logos and early Christian philosophy in the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD had led believers of the time to, morally, become astray, leading to the solution that they were to act in one's best interest, given appropriate reason, to prevent ignorance.[1] The Old Testament of the Bible served as the source of ethics in ancient economic practices. Currency debasement was prohibited given its fraudulent nature and negative economic consequences, which was punished according to Ezekiel 22: 18 – 22, Isaiah 1:25 and Proverbs 25: 4-5.[25] Relationships between economic and religious literature have been founded by the New Testament. For example, James 1:27 states that, “looking after orphans and widows in their distress and keeping oneself unspotted by the world make for pure worship without stain before our God and Father,” which supports the academic argument that the goal of the economic process is to perfect one's personality.[26]

The concept of human capital valuation is evident in the Talmud. For example, an injured worker was considered a slave in the labour market while, for compensation purposes, their worth before and after injury as well as their potential decline in income and consumption was evaluated.[2] The idea of opportunity cost is grounded in the ‘S’kbar B’telio’ (literally meaning, 'lost time') concept in Talmudic literature. In ancient Israel, a Rabbi wasn't to be paid for his work, as it would imply that one is profiting from preaching and interpreting the word of God, but compensated otherwise for the work completed as a Rabbi as a means of survival, given they are not involved in any other profession.[2]

The Qur'an and the Sunnah have guided Islamic economic practice for centuries. For example, the Qur'an bans ribā as part of its focus on the eradication of interest in order to prevent financial institutions operating under the guidance of Islamic economics from making monopolistic returns.[27] Zakat is in itself a system for the redistribution of wealth. The Qu'ran specifies that it is intended solely for: the poor, the needy, zakat administrators, those whose hearts are to be reconciled, those in bondage, those debt-ridden, those who strive for the cause of God, and the wayfarer.[28] The use of Pension Loan Schemes (PLS) and other microfinance schemes exercise this teaching including the Hodeibah micro-finance program in Yemen, and the UNDP Murabahah initiatives at Jabal al-Hoss in Syria.[29]

Culture

Economic ethics attempts to incorporate morality and cultural value-qualities in order to account for the limitation of economics being that human decision making isn't restricted to rationality.[30] This understanding of culture unites economics and ethics as a complete theory of human action.[23] Academic culture has increased interest in economic ethics as a discipline. An increased awareness of the cultural externalities of the actions of economic agents, as well as limited separation between the spheres of culture, has purposed further research into their ethical liability.[23] For example, a limitation of only portraying the instrumental value of an artwork is that it may disregard its intrinsic value and thus shouldn't be solely quantified.[31] An artwork can also be considered a public good due to its intrinsic value, given its potential to contribute to national identity and educate its audience on its subject matter.[31] Intrinsic value can also be quantified given it is incrementally valuable, regardless of whether it is sacred by association and history or not.[32][33]

Application to economic methodologies

Experimental economics

.png)

The development of experimental economics late throughout the 20th century created an opportunity to empirically verify the existence of normative ethics in economics.[34] Vernon L. Smith and his colleagues discovered numerous occurrences that may describe economic choices under the veil of ignorance.[34] Conclusions from following economic experiments indicate that economic agents use normative ethics in making decisions while also seeking to maximise their own payoffs.[35] For example, in experiments on honesty, it is predicted that lying will occur when it increases these payoffs notwithstanding the fact that the results proved otherwise.[35] It is found that people also employ the '50/50 rule' in dividing something regardless of the distribution of power in the decision making process.[34] Experimental economic studies of altruism have identified it as an example of rational behaviour.[34] The absence of an explanation for such behaviour indicates an antithesis in experimental economics that it interprets morality as both an endogenous and exogenous factor, subject to the case at hand.[35] Research into the viability of normative theory as an explanation for moral reasoning is needed, with the experimental design focused on testing whether economic agents under the conditions assumed by the theory produce the same decisions as those predicted by the theory.[36] This is given that, under the veil of ignorance, agents may be 'non-tuist' in the real world as the theory suggests.[36]

Behavioural economics

Ethics in behavioural economics is ubiquitous given its concern with human agency in its aim to rectify the ethical deficits found in neoclassical economics, i.e. a lack of moral dimension and lack of normative concerns.[18] The incorporation of virtue ethics in behavioural economics has facilitated the development of theories that attempt to describe the many anomalies that exist in how economic agents make decisions.[18] Normative concerns in economics can compensate the applicability of behavioural economic models to real economic phenomena. Most behavioural economic models assume that preferences change endogenously, meaning that there are numerous possible decisions applicable to a given scenario, each with their own ethical value.[37] Hence, there's caution in considering welfare as the highest ethical value in economics, as conjectured in academic literature.[37] As a result, the methodology also employs order ethics in assuming that progress in morality and economic institutions is simultaneous, given that behaviour can only be understood in an institutional framework.[18] There are complications in applying normative inferences with empirical research in behavioural economics, given that there's a fundamental difference between descriptive and prescriptive inference and propositions.[18] For example, the argument against the use of incentives that they force certain behaviours in individuals and convince them to ignore risk is a descriptive proposition that is empirically unjustified.[38]

Application to economic sub-disciplines

Environmental economics

Welfare is maximised in environmental economic models when economic agents act according to the homo oeconomicus hypothesis.[39] This creates the possibility of economic agents compensating sustainable development for their private interests, given that homo oeconomicus is restricted to rationality.[39] Climate change policy as an outcome of inference from environmental economics is subject to ethical considerations.[40] The economics of climate change, for example, is inseparable with social ethics.[41] The idea of individuals and institutions working companionably in the public domain, as a reflection of homo politicus, is also an apposite ethic that can rectify this normative concern.[39] An ethical problem associated with the sub-discipline through discounting is that consumers value the present more so than the future, which has implications for inter-generational justice.[42] Discounting in marginal cost-benefit analysis, to which economists view as a predictor for human behaviour,[42] is limited with respect to accounting for future risk and uncertainty.[40] In fact, the use of monetary measures in environmental economics is based on the instrumentalisation of natural things which is inaccurate in the case that they are intrinsically valuable.[41] Other relationships and roles between generations can be elucidated through adopting certain ethical rules. The Bruntland Commission, for example, defines sustainable development as that which meets present needs without compromising the ability of future generations to do so,[43] which is a libertarian principle.[44] Under libertarianism, no redistribution of welfare is made unless all generations are benefited or unaffected.[42]

Political economy

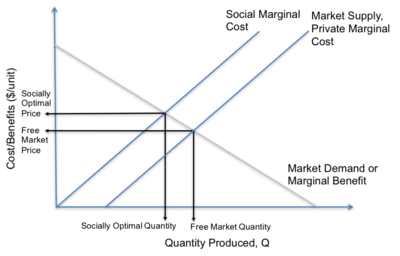

Political economy is a subject fundamentally based on normative protocol, focusing on the needs of the economy as a whole by analysing the role of agents, institutions and markets as well as socially optimal behaviour.[45] Historically, morality was a notion used to discern the distribution of these roles and responsibilities, given that most economic problems derived from the failure of economic agents to fulfil them.[46] The transition of moral philosophy from such ethics to Kantian ethics, as well as the emergence of market forces and competition law, subjected the moral-political values of moral economy to rational judgement.[46] Economic ethics remains a substantial influence to Political Economy due to its argumentative nature, evident in the literature concerning government responses to the global financial crisis. One proposition holds that, since the contagion of the crisis was transmitted through distinct national financial systems, future global regulatory responses should be built on the distributive justice principle.[47] The regulation of particular cases of financial innovation, while not considering critiques of the global financial system, functionally normalises perceptions on the system's distribution of power such that it lessens the opportunities of agents to question the morality of such practice.[47]

Development economics

The relationship between ethics and economics has defined the aim of development economics.[48] The idea that one's quality of life is determined by their ability to lead a valuable life has founded development economics as a mechanism for expanding such capability.[48] This proposition is the basis to the conceptual relationship between it and welfare economics as an ethical discipline, and its debate in academic literature.[48] The discourse is based on the notion that certain tools in welfare economics, particularly choice criterion, hold no value-judgement, and are Paretian given that collective perspectives of utility aren't considered.[49] There are numerous ethical issues associated with the methodological approach of development economics, i.e. the randomised field experiment, much of which are morally equivocal. For example, randomisation advantages some cases and disadvantages others, which is rational under statistical assumptions and a deontological moral issue simultaneously.[50] There are also ethical implications related to the calculus, the nature of consent, instrumentalisation, accountability and role of foreign intervention in this experimental approach.[50]

Health economics

In health economics, the maximised level of well-being being an ultimate end is ethically unjustified, as opposed to the efficient allocation of resources in health that augments the average utility level.[51] Under this utility-maximising approach, subject to libertarianism, a dichotomy is apparent between health and freedom as primary goods given the condition one is necessary to have in order to attain the other.[52] Any level of access, utilisation and funding of healthcare is ethically justified as long as it is accomplishes the desired and needed level of health.[51] Health economists instrumentalise the concept of a need as that which achieves an ethically legitimate end for a person.[51] This, in its entirety, is based on the notion that healthcare as such isn't intrinsically valuable, but morally significant on the grounds that it contributes to this overall well-being.[51] The methodology of analysis in health economics, with respect to clinical trials, is subject to ethical debate. The experimental design should partially be the responsibility of health economists given their tendency to otherwise add variables that have the potential to be insignificant.[53] This increases the risk of under-powering the study which, in health economics is primarily concerned with cost effectiveness, has implications for evaluation. [53]

Application to economic policy

.svg.png)

Academic literature presents numerous ethical views on what constitutes a viable economic policy. Keynes viewed that good economic policies are those that make people good as opposed to those that make them feel good.[1] The 'Verein für socialpolitik', founded by Gustav von Schmoller, insists that ethical and political considerations are critical in evaluating economic policies.[54] Rational actor theory in the policy arena is evident in the use of Pareto optimality in order to assess the economic efficiency of policies, as well as in the use of cost-benefit analysis (CBA), where income is the basic unit of measurement.[19] The use of an iterative decision-making model, as an example of rationality, can provide a framework for economic policy in response to climate change.[55] Academic literature also presents an ethical reasoning to the limitation associated with the application of rational actor theory to policy choice. Given that incomes are dependent on policy choice, and vise-versa, the logic of the rational model in policy choice is circular, hence the possibility of wrong policy recommendations.[19] There are also many factors that increase one's propensity to deviate from the modelled assumptions of decision making.[56] It is argued, under self-effacing moral theory, that such mechanisms as CBA may be justified even if not explicitly moral.[19] The contrasting beliefs that public actions are based on such utilitarian reckonings, and that all policy-making is politically contingent, justifies the need for forecasting which itself is an ethical dilemma.[57] This is founded on the proposition that forecasts can be amended to suit a particular action or policy rather than being objective and neutral.[57][58] For example, the code of ethics of the American Institute of Certified Planners provides inadequate support for forecasters to avert this practice.[57] Such 'canons' as those found in the Code of Professional Ethics and Practices of the American Association for Public Opinion Research is limited in regulating or preventing this convention.[57]

See also

References

- Richards, Donald G. (2017). Economics, Ethics, and Ancient Thought: Towards a virtuous public policy. New York, USA: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-84026-3.

- Wilson, Rodney (1997). Economics, Ethics and Religion: Jewish, Christian and Muslim Economic Thought. London, United Kingdom: Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-349-39334-3.

- Bhatt, Ogaki, Yaguchi, Vipul, Masao, Yuichi (June 2015). "Normative Behavioural Economics Based on Unconditional Love and Moral Virtue". The Japanese Economic Review. 66 (2): 226–246. doi:10.1111/jere.12067.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Hicks, Stephen R. C. (2019). "Ethics and Economics". The Library of Economics and Liberty. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- Price, B.B (1997). Ancient Economic Thought. 11 New Fetter Lane, London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-14930-4.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Aurobindo, Sri (2001). The Upanishads--II : Kena And Other Upanishads. India: Sri Aurobindo Ashram Publication Department. ISBN 81-7058-748-4.

- Michell, H. (2014). The Economics of Ancient Greece. 32 Avenue of the Americas, New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 25. ISBN 978-1-107-41911-7.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Alvey, James E. (2011). "The ethical foundations of economics in ancient Greece focusing on Socrates and Xenophon". International Journal of Social Economics. 38 (8): 714–733. doi:10.1108/03068291111143910.

- Dierksmeier, Claus (2016). Reframing Economic Ethics: The Philosophical Foundations of Humanistic Management. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing AG. p. 5. ISBN 978-3-319-32299-5.

- Tollison, R.D., Hebert, R. F., Ekelund, R. B. (2011). The Political Economy of the Medieval Church. The Oxford Handbook of the Economics of Religion. pp. 308–309.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Levine, Aaron (2010). The Oxford Handbook of Judaism and Economics. New York, USA: Oxford University Press. p. 202. ISBN 978-0-19-539862-5.

- Laffont, Jean-Jacques (November 1975). "Macroeconomic Constraints, Economic Efficiency and Ethics: An Introduction to Kantian Economics". Economica. 42 (168): 430–437. doi:10.2307/2553800. JSTOR 2553800.

- Jasper, Kathryn L. (2012). "The Economics of Reform in the Middle Ages". History Compass. 10 (6): 440–454. doi:10.1111/j.1478-0542.2012.00856.x.

- Ghazanfar, S. M. (2003). Medieval Islamic Economic Thought. London: RoutlegeCruzon. pp. 91. ISBN 0-415-29778-8.

- McMurty, John (1939). Unequal Freedoms: The Global Market as an Ethical System. Toronto, Ontario: Garamond Press. pp. 94, 95. ISBN 1-55193-005-6.

- Bassiry, G.R., Jones, M. (1993). "Adam Smith and the Ethics of Contemporary Capitalism". Journal of Business Ethics. 12 (8): 621–627. doi:10.1007/BF01845899.

- Deng, S., Sebek, B. (2008). Global Traffic: Discourses and Practices of Trade in English Literature and Culture from 1550 to 1700. New York, N.Y: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 246. ISBN 978-1-349-37259-1.

- Rajko, Alexander (2012). Behavioural Economics and Business Ethics: Interrelations and Applications. New York, NY: Routledge. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-415-68264-0.

- Wilber, Charles K. (1998). Economics, Ethics, and Public Policy. Oxford, England: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. ISBN 0-8476-8789-9.

- Fullbrook, Edward (2006). Real World Economics: A Post-Autistic Economics Reader. London, UK: Anthem Press. p. 22. ISBN 1-84331-247-6.

- Choudhury, M. A., Hoque, M. Z. (2004). "Ethics and economic theory". International Journal of Social Economics. 31 (8): 790–807. doi:10.1108/03068290410546048.

- Kirchgässner, Gebhard (2008). Homo Oeconomicus: The Economic Model of Behaviour and Its Applications in Economics and other Social Sciences. New York, USA: Springer. pp. 25–26. ISBN 978-0-387-72757-8.

- Koslowski, Peter (2001). Principles of Ethical Economy. The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers. p. 4. ISBN 0-7923-6713-8.

- Gruchy, Alan G. (July 1948). "The Philosophical Basis of the New Keynesian Economics". Ethics. 58 (4): 235–244. doi:10.1086/290624. JSTOR 2379012.

- North, Dr. Gary (1973). An Introduction to Christian Economics. pp. 5, 6.

- Welch, P.J., Mueller, J. J. (June 2001). "The Relationships of Religion to Economics". Review of Social Economy. 59 (2): 185–202. doi:10.1080/00346760110035581. JSTOR 29770105.

- Kuran, Timur (1995). "Islamic Economics and the Islamic Subeconomy". Journal of Economic Perspectiv. 9 (4): 155–173. doi:10.1257/jep.9.4.155.

- "9: 60 (At-Tawbah)". The Noble Quran. 2016.

- Abdul Rahman, Abdul Rahim (2007). "Islamic Microfinance: A Missing Component in Islamic Banking" (PDF). Kyoto Bulletin of Islamic Area Studies. 1: 38–53 – via Kurenai.

- Koslowski, Peter (2000). Contemporary Economic Ethics and Business Ethics. New York: Springer. pp. 5, 6. ISBN 978-3-642-08591-8.

- Towse, Ruth (2011). A Handbook of Cultural Economics. UK: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited. pp. 173. ISBN 978-1-84844-887-2.

- Groenewegen, Peter (1996). Economics and Ethics?. London: Routledge. p. 43. ISBN 0-415-14484-1.

- Kohen, Ari (2006). "The Problem of Secular Sacredness: Ronald Dworkin, Michael Perry and Human Rights Foundationalism". Journal of Human Rights. 5 (2): 235–256. doi:10.1080/14754830600653561 – via University of Nebraska.

- Storchevoy, Maxim (2018). BUSINESS ETHICS AS A SCIENCE: Methodology and Implications. Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 43, 120. ISBN 978-3-319-68860-2.

- Schreck, Phillpp (2016). "Experimental Economics and Normative Business Ethics". University of St. Thomas Law Journal. 12: 360–380 – via UST Research Online.

- Frances-Gomez, P., Sacconi, L., Faillo, M. (July 2012). "Experimental economics as a method for normative business ethics" (PDF). EconomEtica. Working Papers: 1–27.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Bhatt, V., Ogaki, M., Yaguchi, Y. Normative Behavioral Economics Based on Unconditional Love and Moral Virtue. Japan: INSTITUTE FOR MONETARY AND ECONOMIC STUDIES

- Lunze, K., Paasche-Orlow, M. K. (2013). "Financial Incentives for Healthy Behavior: Ethical Safeguards for Behavioral Economics". American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 44 (6): 659–665. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2013.01.035. PMID 23683984.

- Faber, M., Petersen, T., Schiller, J. (2002). "Homo oeconomicus and homo politicus in Ecological Economics". Ecological Economics. 40 (3): 323–333. doi:10.1016/S0921-8009(01)00279-8.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Beckerman, W., Hepburn, C. (2007). "Ethics of the Discount Rate in the Stern Review on the Economics of Climate Change" (PDF). World Economics. 8: 210 – via Queen's University.

- "Environmental Ethics". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 2015.

- Spash, Clive L. (1993). "Economics, Ethics and Long-Term Environmental Damages" (PDF). Environmental Ethics. 15 (2): 117–132. doi:10.5840/enviroethics199315227.

- World Commission on Environment and Development (1987). Our common future. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780192820808.

- Holden, E., Linnerud, K., Banister, D. (2014). "Sustainable development: Our Common Future revisited". Global Environmental Change. 26: 130–139. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.04.006.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Fleurbaey, M., Salles, M., Weymark, J. A. (2011). Social Ethics and Normative Economics: Essays in Honour of Serge-Christophe Kolm. New York: Springer. p. 20. ISBN 978-3-642-17806-1.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Sayer, Andrew (2000). "Moral Economy and Political Economy" (PDF). Studies in Political Economy. 61: 79–104. doi:10.1080/19187033.2000.11675254 – via Lancaster University.

- Brasset, J., Rethel, L., Watson, M. (March 2010). "The Political Economy of the Subprime Crisis: The Economics, Politics and Ethics of Response" (PDF). New Political Economy. 15: 1–7. doi:10.1080/13563460903553533.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Qizilbash, Mozaffar (2007). "On Ethics and the Economics of Development" (PDF). The Journal of Philosophical Economics. 1: 54–73.

- Archibald, G. C. (November 1959). "Welfare Economics, Ethics, and Essentialism". Economica. 26 (104): 316–327. doi:10.2307/2550868. JSTOR 2550868.

- Baele, S. J. (2013). "The ethics of New Development Economics: is the Experimental Approach to Development Economics morally wrong?" (PDF). The Journal of Philosophical Economics. 7: 1–42 – via University of Exeter.

- Hurley, Jeremiah (2001). "Ethics, economics, and public financing of health care". Journal of Medical Ethics. 27 (4): 234–239. doi:10.1136/jme.27.4.234. PMC 1733420. PMID 11479353 – via BMJ Journals.

- Culyer, Anthony J. (2001). "Economics and ethics in health care" (PDF). Journal of Medical Ethics. 27 (4): 217–222. doi:10.1136/jme.27.4.217. PMC 1733424. PMID 11479350 – via BMJ Journals.

- Briggs, Andrew (December 2000). "Economic evaluation and clinical trials: size matters - The need for greater power in cost analyses poses an ethical dilemma". BMJ. 2 (7273): 1362–1363. doi:10.1136/bmj.321.7273.1362. PMC 1119102. PMID 11099268.

- Clarke, S. (1990). Political Economy and the Limits of Sociology. Madrid, Spain. Retrieved from https://homepages.warwick.ac.uk/~syrbe/pubs/ISA.pdf

- NATIONAL RESEARCH COUNCIL OF THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES (2010). Informing an Effective Response to Climate Change. Washington, D.C.: THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS. p. 92. ISBN 978-0-309-14594-7.

- Monroe, K. R., Maher, K. H. (March 1995). "Psychology and Rational Actor Theory". Political Psychology. 16 (1): 1–21. doi:10.2307/3791447. JSTOR 3791447.

- Wachs, Martin (1990). "Ethics and Advocacy in Forecasting for Public Policy". Business & Professional Ethics Journal. 9 (1/2): 141–157. doi:10.5840/bpej199091/215. JSTOR 27800037.

- Small, G. R., Wong, R. (2001). The Validity of Forecasting. Sydney, Australia: University of Technology Sydney. pp. 12. Retrieved from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/b8a9/69be58495cb72102fbe8ecceacc8641c64a0.pdf

Further reading

- DeMartino, G. F., McCloskey, D. N. (2016). The Oxford Handbook of Professional Economic Ethics. New York, USA: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-976663-5

- Luetge, Christoph (2005). "Economic ethics, business ethics and the idea of mutual advantages". Business Ethics: A European Review. 14 (2): 108–118. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8608.2005.00395.x.

- Rich, A. (2006). Business and Economic Ethics: The Ethics of Economic Systems. Leuven, Belgium: Peeters Publishers. ISBN 90-429-1439-4

- Sen, A. (1987). On Ethics and Economics. Carlton, Australia: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-631-16401-4

- Ulrich, P. (2008). Integrative Economic Ethics: Foundations of a Civilized Market Economy. New York, USA: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-87796-1