Dushanbe

Dushanbe (Tajik: Душанбе, IPA: [duʃæmˈbe]; meaning Monday in Persian,[4][5][6]) is the capital and largest city of Tajikistan. As of January 2020, Dushanbe had a population of 863,400. Until 1929, the city was known in Russian as Dyushambe (Russian: Дюшамбе, Dyushambe), and from 1929 to 1961 as Stalinabad (Tajik: Сталинобод, Stalinobod), after Joseph Stalin.

Dushanbe Душанбe Дюшамбе (Dyushambe, 1924–29), Сталинабад (Stalinabad, 1929–60) | |

|---|---|

.jpg)   .jpg) | |

Seal | |

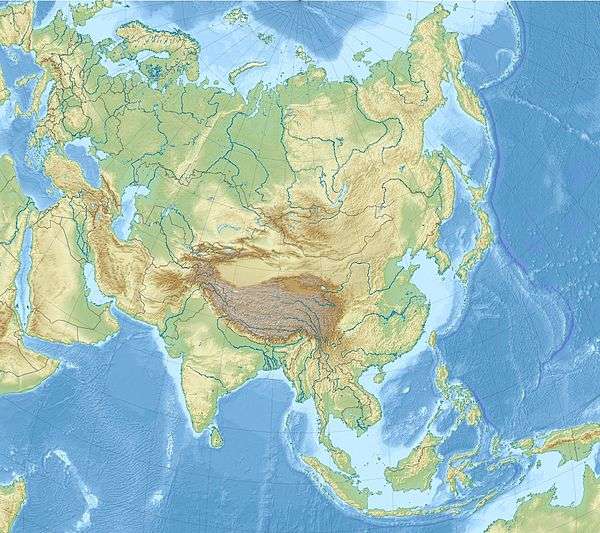

Dushanbe Location of Dushanbe in Tajikistan  Dushanbe Dushanbe (Asia) | |

| Coordinates: 38°32′12″N 68°46′48″E | |

| Country | |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Rustam Emomali |

| Area | |

| • City | 124.6 km2 (48.1 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 823 m (2,700 ft) |

| Population (1 January 2020) | |

| • City | 863,400[2] |

| • Metro | 1,051,200 |

| Time zone | UTC+5 (Tajikistan Time) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+5 (Tajikistan Time) |

| HDI (2017) | 0.728[3] high |

| Website | www |

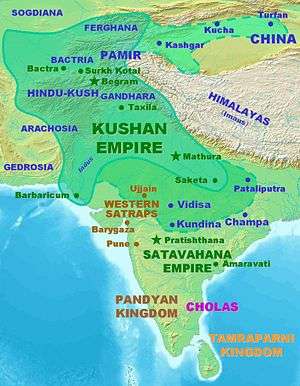

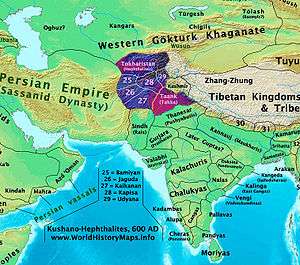

In ancient times, what is now or is close to modern Dushanbe was settled by various empires and peoples, including Mousterian tool-users, various neolithic cultures, the Achaemenid Empire, Greco-Bactria, the Kushan Empire, and the Hephalites. In the Middle Ages, more settlements began near modern-day Dushanbe such as Hulbuk and its famous palace. From the 17th century to the early 20th, Dushanbe began to grow into a market village controlled at times by the Beg of Hisor, Balkh, and finally Bukhara. Soon after the Russian invasion in 1922, the town was made the capital of the Tajik Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic in 1924, which commenced Dushanbe's development and rapid population growth that continued until the Tajik Civil War. After the war, the city became capital of an independent Tajikistan and continued its growth and development into a modern city.

Etymology

.jpg)

Dushanbe was at a crossroads where a large bazaar occurred on Mondays.[7] This gave rise to the name Dushanbe-Bazar (Tajik: Душанбе Бозор, Dushanbe Bozor)[8] from Dushanbe, which means Monday in the Persian language,[9][5] literally – the second day (du) after Saturday (shambe). Its historical name of Stalinabad was named after Joseph Stalin.

History

Ancient times

Mesolithic

In the stone age, Mousterian tool-users inhabited the Gissar valley, near modern-day Dushanbe.[10]

Neolithic

The Hissar culture, Bishkent culture, and Vakhsh culture all where thought to have inhabited the Gissar valley in the second millennium BC.[11][12] Hissar stone tools were discovered within modern-day Dushanbe at the confluence of the Varzob and Luchob.[13]

Map of the Bishkent culture, based on a map printed at page 69 in Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture, which was edited by J. P. Mallory and Douglas Q. Adams, and published by Taylor & Francis in 1997.

Map of the Bishkent culture, based on a map printed at page 69 in Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture, which was edited by J. P. Mallory and Douglas Q. Adams, and published by Taylor & Francis in 1997. Map of the Vakhsh culture, based on a map printed at page 617 in Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture, which was edited by J. P. Mallory and Douglas Q. Adams, and published by Taylor & Francis in 1997.

Map of the Vakhsh culture, based on a map printed at page 617 in Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture, which was edited by J. P. Mallory and Douglas Q. Adams, and published by Taylor & Francis in 1997.

Bronze age

Near the Dushanbe airport, bronze age burials were discovered dating from the end of the second to the beginning of the first millennium BC.[14]

Achaemenid period

Achaemenid dishes and ceramics were found 6 kilometres east of Dushanbe in Qiblai.[15] Archaeological remnants of a small citadel dating to the 5th century BC have been discovered 40 kilometres south[16] and wedge-shaped copper axes have been discovered from the 2nd century BC.[17]

Greco-Bactrian period

Another settlement throughout the region's early history was a small Greco-Bactrian settlement from the end of the 3rd century BC of about 40 hectares in modern-day Dushanbe.[18][17][19]

Kushan period

Near Dushanbe, there was also a Kushan city on the left bank of the Varzob river from the 2nd century BC to 3rd century AD containing burial sites from the time period.[20][17][19] Kushan settlements such as Garavkala, Tepai Shah, Shakhrinau, and Uzbekontepa were founded in this period near Dushanbe.[21][22][23]

Hephalite and Tokharistan period

Ajina Teppe was a Buddhist monastery of the Hephalite period of the late 5-6th century discovered in the Vaksh valley near Dushanbe.[24] Other settlements were discovered near Dushanbe during that period as well, like the town of Shishikona that was unfortunately destroyed during the Soviet era and depopulated during the Mongol invasion.[25][26] International trade began during this period in the Dushanbe region.[27] A castle was also discovered in modern-day Dushanbe dating from the time period.[28] In the 7th century, the Chinese pilgrim Xuanzang visited the region and mentioned the city of Shuman, possibly on the site of modern Dushanbe.[29]

Early Middle Ages

Sasanid silver coins were discovered in the city.[17] After the Arab conquest, in the 10th-12th centuries the medieval city of Hulbuk was developed near Dushanbe which notably contained the palace of the governor of Khulbuk, "an artistic treasure of the Tajik people" among other smaller medieval settlements like Shishikhona.[30] Kharakhamid coins were found that were minted from 1018-1019 in Dushanbe.[31]

Late Middle Ages

Other, smaller settlements were found from the Late Middle Ages after the Mongol invasion. These included Abdullaevsky, and the Shainak settlement. The region of Dushanbe was controlled during this time period by different empires, including the Timurid Empire.[32]

Market town

The first time Dushanbe appeared in the historical record, in a letter sent from the Balkh khan Subhonquli Bahodur to Fyodor Alekseevich, the Tsar of Russia, was in 1676, called "Kasabai Dushanbe," when the village was under the control of Balkh.[33][34] This reflected Dushanbe's status as a town, originally taking the name Dushanbe (Monday) due to the large bazaar in the village that operated on Mondays. Dushanbe's location between the caravan routes heading east-west from the Hissar Valley through Karategin to the Alay Valley, and north-south to the Kafirnigan River and then to Vaksh Valley and Afghanistan through the Anzob Pass from the Fergana and Zeravshan valleys that ultimately led traders to Bukhara, Samarkand, the Pamirs, and Afghanistan incentivized the development of its market.[17][4][35] At the time, the town had a population of around 7-8 thousand with around 500-600 households.[36]

By 1826, the town was called Dushanbe Qurghan (Tajik: Душанбе Қурғон, Dushanbe Qurghon, with the suffix qurƣon from Turkic qurğan, meaning "fortress") Russified as Dyushambe (Дюшамбе). The first map showing Dyushambe was drafted in 1875. It had a caravanserai, a stopping point for travelers to Samarkand, Khujand, Kulob and the Pamirs. It boasted 14 mosques and 2 madrasses at the turn of the century. At that time, the town was a fortress on a steep bank on the left bank of the Varzob River with 10,000 residents.[36][37] It was also a center for weaving, tanning, and ironsmelting production in the region. Control over it was long exercised by the Beg of Hisor but in 1868, it was given to the Emir of Bokhara by the Tsarist government.[38] The first hospital in the village was constructed in 1915 by Russian investment[39] and an early railroad was proposed to connect the market town in 1909, but was abandoned after a review determined the venture would not be profitable.[40]

In 1920, the last Emir of Bukhara briefly took refuge in Dushanbe after being overthrown by the Bolshevik revolution. He fled to Afghanistan after the Red Army conquered the area the next year, March 4 1921.[41][42] In February 1922, the town was taken by Basmachi troops led by Enver Pasha after a siege,[43] but on 14 July 1922 again came under the power of the Bolsheviks[44][45] soon before the death of Enver Pasha on August 4 1922 outside of Dushanbe.[41][46] It was a part of the Bukharan PSR until the formation of the Tajik ASSR.[47]

Capital of the Tajik ASSR and the beginnings of development

Dushanbe was proclaimed the capital of the Tajik Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic as a part of the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic in October 1924 and the government started to function formally on March 15 1925.[48][49][38] The population during the struggle declined from an already meager 3140 in 1920 to only 283 in 1924.[38][40]

To aid in the recovery, the Soviet authorities temporarily exempted much of the population from having to pay taxes. On August 12th 1924 the first newspaper of the village, Voice of the East, was published in Arabic and soon after a Russian-language paper, Red Tajikistan, began publication. Power plants and electricity were introduced to Dushanbe during this time. In 1924 the first regular plane route began from Dushanbe to Bukhara and another from Dushanbe to Tashkent, and the post office was set up.[40] In 1923, the Soviets created Dushanbe's first telegraph link to Bukhara and initiated its first railroad to Termez.[38] Construction on the railroad began on June 24 1926, and it was completed in November 1929, connecting Dushanbe with the Trans-Caspian railroad and kickstarting economic growth.[34] In 1925, the first boy's boarding school was constructed in the capital.[40] On September 1 1927, the first pedagogical college opened in Dushanbe and in November the motor road from Dushanbe to Kulob was completed.[49] Tajiks from the countryside were given assistance and free land plots in the capital to increase its population and development.[40]

Capital of the Tajik SSR

A Tajik Soviet Socialist Republic separate from the Uzbek SSR was created in 1929, and its capital Dyushambe was renamed Stalinabad (Russian: Сталинабад; Tajik: Сталинобод Stalinobod) for Joseph Stalin on 19 October 1929, which incorporated the nearby villages of Shohmansur, Mavlono, and Sari Osiyo.[34][50][49]

Reasons for selection

Dushanbe was chosen instead of larger-populated villages in Tajikistan because of its role as a crossroads of Tajikistan because of its large market that served as a meeting place for much of Tajikistan's population. Along with its market, there was a lively livestock trade as well as trade in fabrics, leather, tin products, and weapons.[51]

Dushanbe also boasted the only Jewish population in the Tajjik SSR, whom were involved in trade and in loaning money, financing much of the Red Army during its conquest of the region.[40] When the Emir moved to the city, however, the Jewish population's property was plundered and the Jews were relocated to Gissar. They were only let back into Dushanbe with its conquest by the Red Army.[52]

The mild Mediterranean climate was another reason Soviet authorities chose the city as the capital.[40]

Dushanbe was also official recognized as the capital of the Emirate of Bukhara during its waning days as it served as the last refuge of the last Emir of Bukhara during its conquest by the Soviet Union, possibly another motivating factor for the decision to establish the new ASSR's capital in the village.[51]

Later development

In the years that followed, the city developed at a rapid pace.[17] The Soviets transformed the area into a center for cotton and silk production, and tens of thousands of people relocated to the city. The population also increased with thousands of ethnic Tajiks migrating to Tajikistan from Uzbekistan following the transfer of Bukhara and Samarkand to the Uzbek SSR as part of national delimitation in Central Asia.[46] Industry during the time period was limited, focused on local production.[38] The first bus line began operating in 1930. and in 1940, Komsomolskoye Lake was constructed in the city.[40]

Many of these projects occurred under the mayoralty of Abdukarim Rozykov, one of the first mayors of Dushanbe, from 1925-1932, who sought to transform it into a "model communist city" through modernization and urban planning. Mikhail Kalitin continued the industrial development of Dushanbe, building the Komsomolskoye Lake and promoting industry in the city.[53]

Several architects played a major role in the city's construction in a group headed by Peter Vaulin. He drew up a piece of legislation called "On the construction of the city of Dushanbe" which the city adopted on April 27 1927. He implemented a constructivist design, learned from his meeting with Le Corbusier in Moscow in 1929.[54] In 1934 and 1935, the Griprogor Institute, based in Leningrad, created a master plan for the construction of Dushanbe. It was approved on March 3 1938. The city center during the reconstruction shifted to Red Square and Frunze Park, the location of many workers demonstrations and military parades into the forties. The first skyscraper in Dushanbe, the hotel Dushanbe, was erected in 1964.[49] High-rise buildings began to be developed in the mid-70s against the wishes of the Tajik Institute of Earthquake Engineering and Seismology, which viewed such developments as dangerous in an earthquake which they predicted would occur in the near future.[35]

During World War 2, the population of Dushanbe and Tajikistan swelled with 100,000 evacuees from the front that led to the deployment of 17 hospitals in the city.[55] The city's industry also greatly increased during the war, as the Soviets wanted to move critical infrastructure far behind enemy lines, and industries like textile manufacturing and food processing began to grow.[38] In 1954, there were 30 schools in the city, a medical institute named after Avicenna, the Stalinabad Academy of Sciences, the University of Stalinabad, which was founded in 1947 and had 1,500 students,[56] and the Stalinabad Pedagocial Instute for Woman, established on September 1 1953.[57]

In 1960, gas supply reached the capital through a gas pipeline opened from Kyzyl to Tumshuk to Dushanbe. On 10 November 1961, as part of de-Stalinization, Stalinabad was renamed back to Dushanbe, the name it retains to this day.[58] In the 1960s, under the leadership of Mahmudbek Narzibekov, the first zoo was built in the city along with a plan to end the housing shortage and provide free apartments.[53] The Nurek Dam, which would have been the tallest dam in the world, was started 90 kilometres south east of Dushanbe during that time period. It was a megaproject meant to showcase Soviet innovation and development in Tajikistan, but the project was cancelled in the 1970s because of stagnating Soviet economic growth.[59][60]

On August 2 1979 the population of Dushanbe reached 500,000.[49]

Riots and unrest

In the 1980s, environmental problems and crime began to increase. Mass violence, hooliganism, binge drinking, and violent assaults were becoming more common in Dushanbe. There was an attack on foreign students at the Agricultural Institute in 1987 and a riot in the Pedagogical Institute two years later.[61] Increasing regionalism also destabilized the SSR.

On February 10-11, 300 demonstrators at the Communist Party Central Committee building after it was rumored that the Soviet government planned to relocate tens of thousands of Armenian refugees to Tajikistan. In reality, only 29 Armenians went to Dushanbe and were housed by their family members. However, the crowd kept growing in size to 3 to 5 thousand people until violence began in the city. Martial law was quickly declared and troops were sent in to protect ethnic minorities and defend against vandalism and looting. The number of people protesting increased significantly, however, and they attacked the Central Committee building. The 29 Armenians were quickly evacuated on an emergency flight after shots were fired.[62]

A few days after, and with looting still occurring throughout the city, demonstrators created the Provisional People’s Committee or the Temporary Committee for Crisis Resolution which put forward demands such as "the expulsion of Armenian refugees, the resignation of the government and the removal of the Communist Party, the closure of an aluminium smelter in western Tajikistan for environmental reasons, equitable distribution of profits from cotton production, and the release of 25 protesters taken into custody."[62]

Many high ranking officials resigned and the protector's goal of toppling the government was close to being successful, but Soviet troops moved into the city, declared the demands illegal, and rejected the resignation of the high ranking officials. 16-25 people were killed in the violence and many if not most were Russian.[62]

The riots were largely fueled by concerns about housing shortages for the Tajik population, but they coincided with a wave of nationalist unrest that swept Transcaucasia and other Central Asian states during the twilight of Mikhail Gorbachev's rule.[63]

After the increase of organized opposition from the Democratic Party of Tajikistan and Rastokhez, glasnost by Gorbachev, economic contraction, and increased opposition by regional elites, Qahhor Mahkamov disbanded the Communist Party of Tajikistan on August 27 1991 and quit the party the next day. On September 9 1991 Tajikistan's government declared independence from the Soviet Union.[64]

Capital of Tajikistan

Dushanbe became the capital of an independent Tajikistan on September 9 1991.[64]

Tajikistani Civil War

On November 24 1991 Rahmon Nabiev was elected President of Tajikistan, defeating Davlatnazar Khudonazarov soon after Tajikistan declared independence. Iran, the United States, and Russia soon opened embassies in Dushanbe. Nabiev was soon forced to resign before the government abolished the office of president and chose Emomoli Rahmon as head of state; in 1994 the office of president was re-established with Rahmon chosen to be president.[49] Dushanbe was controlled by the Russian-backed government during most the Tajikistani Civil War, although the Islamist and Democratic United Tajik Opposition managed to capture the capital in 1992 before 8000 Russian-backed and Uzbekistani-backed government troops regained control of Dushanbe.[65] Most of the Russian population fled the capital during the violence of this time period while large amounts of rural Tajiks moved in; by 1993, more than half had fled.[34][66] The factions during the civil war were organized primarily upon regional lines.[65] The war was ended by a June 27 1997 armistice, administered by the UN, that guaranteed the opposition 30% of the positions in the government.[67]

Modern day

In 2000, Dushanbe received internet access for the first time.[49] In 2004, the UNESCO declared Dushanbe as a city of peace.[68] Mahmadsaid Ubaidulloev was declared mayor of Dushanbe in 1996, after during the civil war era many said he was in real control of the government.[69] He was the mayor of the capital for the longest term of any mayor, of 21 years, until 2017.[53]

In January 2017, Rustam Emomali, current President Emomali Rahmon's son, was appointed Mayor of Dushanbe, a move which is seen by some analysts as a step to reaching the top of the government.[70]

Geography

Dushanbe is situated at the confluence of two rivers, the Varzob and Kofarnihon, 750-930 meters above sea level. The north and east of the city is bounded by the Gissar range.[17]

Climate

Dushanbe features a Mediterranean climate (Köppen: Csa),[71] with some continental climate influences (Köppen: Dsa) due to the nearby glaciers and moutain range.[17][71] The summers are hot and dry and the winters are chilly, but not very cold. The climate is damper than other Central Asian capitals, with an average annual rainfall over 500 millimetres (20 in) as moist air is funneled by the surrounding valley during the winter and spring. Winters are not as cold as further north owing to the shielding of the city by mountains from extremely cold air from Siberia. January 2008 was particularly cold, and the temperature dropped to −22 °C (−8 °F).[72]

| Climate data for Dushanbe (1961–1990, extremes 1951–2012) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 21.6 (70.9) |

23.1 (73.6) |

30.6 (87.1) |

35.6 (96.1) |

38.8 (101.8) |

43.0 (109.4) |

43.3 (109.9) |

45.0 (113.0) |

40.6 (105.1) |

36.8 (98.2) |

31.7 (89.1) |

24.3 (75.7) |

45.0 (113.0) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 7.9 (46.2) |

10.2 (50.4) |

15.2 (59.4) |

22.1 (71.8) |

27.0 (80.6) |

33.1 (91.6) |

35.8 (96.4) |

34.3 (93.7) |

30.7 (87.3) |

24.2 (75.6) |

17.1 (62.8) |

10.8 (51.4) |

22.4 (72.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 3.0 (37.4) |

5.0 (41.0) |

9.7 (49.5) |

15.7 (60.3) |

20.0 (68.0) |

24.8 (76.6) |

26.9 (80.4) |

25.1 (77.2) |

20.9 (69.6) |

15.5 (59.9) |

10.3 (50.5) |

5.8 (42.4) |

15.2 (59.4) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −2.0 (28.4) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

4.2 (39.6) |

9.3 (48.7) |

13.0 (55.4) |

16.5 (61.7) |

17.9 (64.2) |

15.9 (60.6) |

11.1 (52.0) |

6.7 (44.1) |

3.5 (38.3) |

0.8 (33.4) |

8.1 (46.5) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −26.6 (−15.9) |

−17.3 (0.9) |

−13.4 (7.9) |

−7.8 (18.0) |

1.2 (34.2) |

8.4 (47.1) |

10.9 (51.6) |

8.1 (46.6) |

1.9 (35.4) |

−4.4 (24.1) |

−13.5 (7.7) |

−19.5 (−3.1) |

−26.6 (−15.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 66.3 (2.61) |

75.4 (2.97) |

107.5 (4.23) |

105.0 (4.13) |

66.0 (2.60) |

5.5 (0.22) |

3.2 (0.13) |

0.5 (0.02) |

3.1 (0.12) |

30.6 (1.20) |

44.7 (1.76) |

59.8 (2.35) |

567.6 (22.35) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 8.5 | 9.1 | 13.4 | 9.8 | 7.8 | 1.5 | 0.7 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 3.7 | 5.3 | 8.1 | 68.8 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 69 | 67 | 65 | 63 | 57 | 42 | 41 | 44 | 44 | 56 | 63 | 69 | 57 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 120 | 121 | 156 | 198 | 281 | 337 | 352 | 338 | 289 | 224 | 164 | 119 | 2,699 |

| Source 1: Deutscher Wetterdienst[73] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: NOAA (sun, 1961–1990)[74] | |||||||||||||

Districts

Dark Green: Shah Mansur

Purple: Ismail Samani

Light Green: Avicenna

Yellow: Ferdowsi

Dushanbe is divided into the following districts:

| District name | Former name | Area,

km² [75] |

Population,

persons (2019)[75] |

District Chairman[76] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ismail Samani (Tajik: Исмоили Сомонӣ, Ismoili Somoni; Persian: اسماعیل سامانی) | October (Октябрьский) | 25.8 | 148,700 | Sami Sharif Hamid |

| Avicenna (Sino) (Tajik: Абӯалӣ Ибни Сино, Abūali Ibni Sino; Persian: ابوعلی ابن سینا) | Frunzensky (Фрунзенский) | 43.8 | 326,100 | Salimzoda Nusratullo Faizullo |

| Ferdowsi (Tajik: Фирдавсӣ, Firdavsi; Persian: فردوسی) | Central (Центральный) | 29.1 | 209,000 | Yusufi Muhammadrahim |

| Shah Mansur (Tajik: Шоҳмансур, Shohmansur; Persian: شاه منصور)[77] | Railway (Железнодорожный) | 27.9 | 162,600 | Bilol Ibrohim |

Main sights

- Tajikistan National Museum

- National Museum of Antiquities

- Vahdat Palace

- Dushanbe Flagpole—It is the second tallest free-standing flagpole in the world, at a height of 165 metres (541 feet),[78]

- Dushanbe Zoo

- Rudaki Avenue

- Gurminj Museum of Musical Instruments[79]

Demographics

Ethnicity

| Year | Tajik | Russian | Uzbek | Tatar | Ukrainian | Korean | German | Turkmen |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1970[38] | 26 | 42 | ||||||

| 1979[38] | 30.7 | 39 | ||||||

| 1987 | 75 | 3 | 10 | |||||

| 1989 | 39.1 | 32.4 | 10.4 | 4.1 | 3.5 | |||

| 2003[80] | 83.4 | 5.1 | .7 | .3 | .1 | 1.1 | ||

| 2010[81] | 89.5 | 6.7 | .3 | .1 | ||||

| 2016 | 84.4 | 4.1 | 9.1 |

- in 1987 Dushanbe's population was about 796,000 and was made up of ethnic Tajiks (75%), Uzbeks (10%), ethnic Russians (3%), and others (12%);

- in 1989 the population was 39.1% Tajik, 32.4% Russian, 10.4% Uzbek, 4.1% Tatar, and 3.5% Ukrainians. The remaining 10.4 percent included Jews, Kirghiz, Turkmen, Korean and others

- in 2016 was about 802,400 and was made up of ethnic Tajiks (c. 84.4%), Uzbeks (9.1%), Russians (4.1%), and others (2.4%).

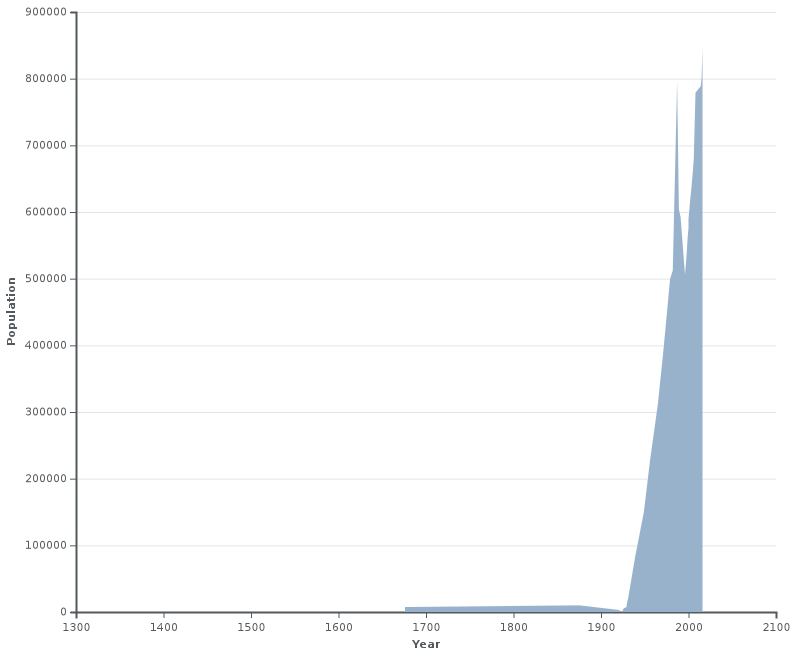

Population

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1676 | 7,500 | — |

| 1875 | 10,000 | +33.3% |

| 1920 | 3,140 | −68.6% |

| 1924 | 283 | −91.0% |

| 1926 | 5,600 | +1878.8% |

| 1929 | 7,298 | +30.3% |

| 1930 | 15,540 | +112.9% |

| 1931 | 20,360 | +31.0% |

| 1933 | 35,818 | +75.9% |

| 1939 | 82,540 | +130.4% |

| 1949 | 150,000 | +81.7% |

| 1956 | 227,000 | +51.3% |

| 1965 | 312,000 | +37.4% |

| 1971 | 388,000 | +24.4% |

| 1979 | 500,000 | +28.9% |

| 1982 | 512,000 | +2.4% |

| 1987 | 796,000 | +55.5% |

| 1989 | 604,000 | −24.1% |

| 1991 | 592,000 | −2.0% |

| 1996 | 505,600 | −14.6% |

| 1998 | 538,600 | +6.5% |

| 1999 | 592,000 | +9.9% |

| 2000 | 575,900 | −2.7% |

| 2001 | 589,400 | +2.3% |

| 2002 | 604,000 | +2.5% |

| 2003 | 619,400 | +2.5% |

| 2004 | 631,700 | +2.0% |

| 2005 | 646,400 | +2.3% |

| 2006 | 679,400 | +5.1% |

| 2008 | 661,000 | −2.7% |

| 2014 | 779,000 | +17.9% |

| 2015 | 788,700 | +1.2% |

| 2016 | 802,700 | +1.8% |

| 2019 | 846,400 | +5.4% |

| Year | Population |

|---|---|

| 1676 | 7,000-8,000[36] |

| 1875 | 10,000[36] |

| 1920 | 3,140 |

| 1924 | 283[38] |

| 1926 | 5,600[38] |

| 1929 | 7,298[39] |

| 1930 | 15,540[39] |

| 1931 | 20,360[39] |

| 1933 | 35,818[39] |

| 1939 | 82,540[39][40] |

| 1949 | 150,000[57] |

| 1956 | 227,000 |

| 1965 | 312,000 |

| 1971 | 388,000 |

| 1979 | 500,000[49] |

| 1982 | 512,000[40] |

| 1987 | 796,000[82] |

| 1989 | 604,000[38] |

| 1991 | 592,000[83] |

| 1996 | 505,600[84] |

| 1998 | 538,600 |

| 1999 | 561,200 |

| 2000 | 575,900 |

| 2001 | 589,400 |

| 2002 | 604,000 |

| 2003 | 619,400 |

| 2004 | 631,700 |

| 2005 | 646,400 |

| 2006 | 661,000[85] |

| 2008 | 679,400[86] |

| 2014 | 779,000 |

| 2015 | 788,700[87] |

| 2016 | 802,700[88] |

| 2019 | 846,400 |

| Population pyramid 2020 | ||||

| % | Males | Age | Females | % |

| 0.1 | 85+ | .1 | ||

| 0.1 | 80–84 | .2 | ||

| 0.2 | 75–79 | .3 | ||

| 0.4 | 70–74 | .5 | ||

| 0.8 | 65–69 | .8 | ||

| 1.3 | 60–64 | 1.3 | ||

| 2.0 | 55–59 | 2.0 | ||

| 2.3 | 50–54 | 2.5 | ||

| 2.5 | 45–49 | 2.8 | ||

| 2.6 | 40–44 | 2.9 | ||

| 3.1 | 35–39 | 3.2 | ||

| 4.8 | 30–34 | 4.1 | ||

| 6.5 | 25–29 | 4.7 | ||

| 6.2 | 20–24 | 4.8 | ||

| 5.5 | 15–19 | 4.5 | ||

| 4.7 | 10–14 | 4.4 | ||

| 4.5 | 5–9 | 4.2 | ||

| 4.7 | 0–4 | 4.0 | ||

Religion

Transportation

Air transport

History

The first flight to the city was from Bukhara on September 3 1924 of the Junkers F-13 aircraft piloted by Rashid Beck Ahriev and Peter Komarov; the service began to run three times a week. In 1927, the second air route in the Soviet Union was opened from Tashkent to Samarkand to Termez to Dushanbe on the Junkers F-13, two years before the introduction of automobiles and five before the railway. A small Stalinabad airport was created, and in 1930 a first-class airport was constructed in the city. The first scheduled flight from the city to Moscow began in 1945 on the Li-2.[49][89] The state airline, Tojikiston, which is now known as Tajik Air, was created in 1949. In the 50s and 60s, many new aircraft were introduced to the Tajik Civil Air Fleet. The Tajik Civil Aviation Administration won first place in the USSR for efficiency in the 1980s.[89]

Dushanbe International Airport

The city is served by Dushanbe International Airport which, as of April 2015, had regularly scheduled flights to major cities in Russia, Central Asia, Delhi, Dubai, Frankfurt, Istanbul, Kabul, and Ürümqi amongst others. Tajik Air had its head office on the grounds of Dushanbe Airport in Dushanbe.[90] Somon Air, which opened in 2008, has its head office in Dushanbe.[91][89] The government planned to devote .18% of Tajikstan's GDP to the development of aviation in a large part in Dushanbe.[89] Japanese investors planned to modernize the airport and its cargo terminal and build a new terminal worth around $42 million.[92]

Rail transport

History

The first rail line in Dushanbe, which was 245 kilometres long, was built from 1926 to 1929 and opened on September 10 1929 from Vhadat to Dushanbe to Termez[93][94] that ultimately connected Dushanbe with Moscow. In 1933 and 1941 two other narrow-gauge railroad lines were laid from Dushanbe, to Gulpista and Kurgan-Tyube. In 2002 a new railroad administration began that modernized the system.[95]

Modern system

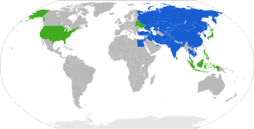

Today, Tajikistan's principal railways are in the southern region and connect Dushanbe with the industrial areas of the Gissar and Vakhsh valleys and with Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan and Russia.[96] Tajikistan's railways are owned and operated by Tajik Railway. In the early 2000s a new railway line from Dushanbe to Gharm to Jirghatol was construed that would connect the country to Russia, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan while not going through Uzbekistan. A proposed line from Dushanbe to Herat and Mashad is also being promoted by the government.[94] On June 18 2018 the first railway between Dushanbe and Nur-Sultan, the capital of Kazakhstan, completed its trip through Uzbekistan's Karakalpakstan region.[97] Tajikstan's northern railway system remain isolated from its other railway lines, including those of Dushanbe. There is also a service from Dushanbe to Khujand and the northern Uzbek town of Pakhtaabad.[94]

Trolleybus system

History

.jpg)

The Dushanbe trolleybus system began on April 6 1955 when a trolleybus administration was organized in the city. On May 1 1955 the first Trolza trolleybus began operation on Lenin Avenue, the main avenue of Dushanbe. Routes continued to be added in 1957 and 1958 and in 1967 9 routes were opened and the length of the network reached 49 kilometres. The collapse of the Soviet Union led to a crisis in the system, as fuel increased in price and looting became a consistent problem, with one incident occurring at the central bus station leading to the temporary suspension of lines. During the period, the number of trolleybuses declined from a high of 250 during the late 1980s to only 45-50. 100 New trolleybuses were ordered in 2004 which were delivered a couple years after and aided in the resumption of service.[98]

Modern day

In 2020, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development gave $8 million dollars to repair the system. As of 2020, Dushanbe had 7 trolleybus routes with 11 million passengers a years.[99][100] While trolleybuses where the main mode of transport in the Soviet era, today they account for only 2% of motorized trips.[101]

Fleet

Dushanbe trolleybuses are based upon the ZiU-9 trolleybus design.

Metro system

The construction of an above-ground metro system is due to begin in 2025.[99] The first aerial metro line is expected to be completed in 2040 and connect the Southern Gate and Gulliston (circus area).[103]

Automobiles

Automobiles are the main form of transportation in the country and in Dushanbe. One major road goes through the mountains from Khujand to Dushanbe through the Anzob Tunnel, constructed by an Iranian operator.[104] A second major roads goes east from Dushanbe to Khorog in the Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Province and then goes to Murghab and then onto China or Kyrgyzstan.[105]

Many highway and tunnel construction projects are underway or have recently been completed (as of 2014). Major projects include rehabilitation of the Dushanbe – Chanak (Uzbek border), Dushanbe – Kulma (Chinese border), Kurgan-Tube – Nizhny Pyanj (Afghan border) highways and construction of tunnels under the mountain passes of Anzob, Shakhristan, Shar-Shar[106] and Chormazak.[107]

Culture

Music

During the 19th century, shashmaqam was the most prevalent music in Tajikistan. While Soviet authorities labeled it as "music composed for the Emir" and repressed it, in modern times it has gained greater popularity.[108]

During the Soviet period, the Soviet Union encouraged the development of music in Dushanbe, a less culturally crowded place then typical Russian megacities. Sergei Artemevich Balasanyan, an Armenian, was one composer who originally went to Dushanbe from 1936-1943 to prepare the SSR for an upcoming Tajik cultural festival to be held in Moscow. While we was there, he described himself as a "composer, social-musical worker, folklorist, and pedagogue." He also became the head of the Tajik Composer's Union and the artistic lead of the opera house.[108]

Another musician to come to Dushanbe during the Soviet period was Aleksandr Lensky, a Moldovan who came to Tajikistan in 1937. He was the artistic director of the Lahuti Theatre, director of the Tajik Phillharmonic, and first secretary of the Tajik Union of Composers. He also composed the first Tajik opera and many orchestral pieces.[108]

Opera houses

The Tajik Opera and Ballet Theater, whose building was named after Sadriddin Ayni and was the first opera house in Dushanbe, was founded in 1936.[109][110] The first opera performed, the first in history of Tajikistan, was The Vose Uprising and detailed a peasants' revolt in eastern Bukhara in the late 19th century.[111] One notable singer of the opera was Hanifa Mavlianova.[112] The opera theater continued operating to this day, winning the Order of Lenin.[109] At various times the opera house performed operas on modern, historical, national, revolutionary, and heroic themes.[110]

Symphonies

The Tajik Phillharmonic Society was founded in 1938; today, it is named after after Akasharif Juraev.[113][114] Another orchestra in Dushanbe is the Opera Orchestra.[115] The State Symphony Orchestra of Tajikistan was founded in 2016, and its first concert took place on September 9 2016.[116][117]

Dance

The Tajik Opera and Ballet theater also had the first ballet performed in Dushanbe in 1941, entitled Two Roses and the ballet troupe gradually grew over time.[112][118] The troupe was improved with graduates from the Leningrad Choreographic School with ballet dancers such as Malika Sabirova.[112] The theater was refitted in 2009 and continues operating to this day.[119]

Education

A number of educational facilities are based in Dushanbe:

Media

Newspapers and magazines

The first newspaper published in Tajik was Bukhara Sharif in Kagan on March 11 1912 and published by leaders of the Jadid movement like Mirzo Jalol Yusufzoda. The purpose of the newspaper was to "be a scientific, literary, directional, subject, and economic publication that will strive for the spread of civilization and the idea." Soon after, however, Ivan Petrov requested that the Emir of Bukhara close the paper, which he did on January 2 1913. The newspaper in its short time in existence printed 12 works of Tolstoy.[120]

The first printing press in Tajikistan was created in August 1924, the Tajik State Publishing House, the Donish Publishing House was founded in 1944, and the Maorif Publishing House was created in 1975.[120]

Oina and Mullo Nasreddin were two of the earliest Tajik language magazines. The Zvezda Vostok magazine was published in Tajik in the early 1920s in support of the October Revolution.[120]

The first Soviet newspaper distributed in Tajikistan was Shulai Inkilob (Flame of the Revolution) as propaganda for the Soviet government in 1919. It was distributed throughout Tajikistan and was the main Tajik language newspaper that opposed the previous Emirate and was clearly in support of communism, the October Revolution, and the Bukharan Communist Party.[120]

The first Soviet newspaper published in Tajikistan was Po basmachi which detailed the conditions of the Red Army in Tajikistan in 1923 during the Basmachi movement. In 1924, the newspaper Voice of the East, the first Soviet government newspaper in Tajik was published in Dushanbe and was a forum for much of the poetry and literature of the young republic. In 1925, the official newspaper of Soviet Tajikistan was"Bedorii tochik (Awakening of the Tajiks). An Uzbek-language paper, Red Tajikistan, was published in Tajikistan as well.[120]

Sadriddin Ayni also published many newspapers such as Bukhara News, Horpustak, and Flame of the Revolution.[120]

In 1929, the newspaper Red Tajikistan came into print with a large daily circulation of 5000. In the 1930s Komsomolets Tadzhikistana was published as a communist paper intended for the youth of Tajikistan. Many other newspapers were published during this time as well.[120]

The press often emphasized the collective farming system and the newspaper Dehkoni Kambagal was popular among farmers.[120]

During World War 2 newspaper production was strained as raw materials became increasingly scarce and their numbers were reduced. After the war, the many newspapers from the 30s began to be produced once again. In the 60s and 70s the newspaper Communist of Tajikistan gained prominence, winning the Order of the Red Banner of Labor. International cooperation also began to be emphasized during the time period.[120]

In the 1980s, Maorif va Madaniyat, an influential public and literary paper was divided into two editions, a cultural and pedagogical one. The Culture of Tajikistan newspaper was renamed Literature and Art and became influential in the country.[120]

During perestroika, newspaper began to embrace more liberal and democratic ideas. One of the first to do this was the Komsomol of Tajikistan. Farkhang, a new literary magazine, published national Tajik and Islamic literature banned before such as the Masnavi. The Sukhan newpaper, published by the Union of Journalists of Tajikistan, was a leading voice for liberalism and perestroika in the republic, writing about topics such as freedom of speech, democratization, and the opposition. The first publication not released by the state was from Rastokhez, printed in Lithuania and delivered to Dushanbe. The Democratic Party of Tajikistan published a paper, Justice, in Dushanbe as well which had a circulation of 25000. Charogi Ruz, or Light of Day, was the first private publication in Dushanbe, and advertised itself as the free tribune for youth. Free publications such as Oinai zindagi (by trade unions), Somon, Haftgandzh, and others began to form.[120] Today, Charogi Ruz is known for its sharp criticism of the ruling government.[121]

In August 1999, there were officially 199 newspapers, although only 17 of those appear regularly.

Some of the most widely circulated national government publications are Dzhumhuriet (Respublika) and Narodna Gazeta. In addition to the state news agency Khovar (News), there are several private newspapers, including Asia-Plus, which regularly publishes (along with the state agency) in Russian and English printed and electronic messages and reports on political, social and economic issues.[122]

Radio

In 1924 a radio station was built in Dushanbe for military communication. On April 10 1930 the first radio broadcast was heard by civilians in Tajikistan, from Moscow. It functioned as a news source and a source of Soviet propaganda. The first station, in Dushanbe, mainly focused on retransmitted broadcasts from Moscow and radios gradually became more prevalent in the country. While development slowed during World War 2, afterwards Tajikistan received higher broadband and quality radio stations and broadcasts.[120]

In 1977, locally-created radio broadcasts were able to be transmitted from Dushanbe thanks to the construction of the Radio House in the city. In 2000, the Sadoi Dushanbe Radio was created, and today that is one of the four programs broadcast in Dushanbe.[120]

As of August 1999 government radio is broadcast throughout the nation. Radio Liberty, the BBC, and Sadoi Khuroson are also broadcast in Tajik, although no independent radios were operating.[122]

Television

On November 7 1959 the first television center was created in the republic, the Tajik Television Studio. In 1967 programs for Moscow and Tashkent were broadcast in the country and on November 15 1975 color television was introduced.[120]

As of August 1999 12 to 15 stations broadcast consistently. Many Russian language channels like ORT, RTR, and TV-6 were broadcast.[122]

International relations

Sister cities

Dushanbe is twinned with:[17]

Boulder, Colorado

In 1982, Mary Hey and Sophia Stoller started an initiative to make Dushanbe a sister city of Boulder even though during that time they were on opposite sides of the Cold War. In 1987, the mayor of Dushanbe, Maksud Ikramov, officially made Boulder a sister city of Dushanbe. Exchange students, tourism, and art exchanges began between the two cities. The Tajik Teahouse was sent from Dushanbe to Boulder in 1990. During the civil war, Boulder sent humanitarian aid to Dushanbe.[126]

International conferences

Many international conferences have been held in Dushanbe, such as the International Conference on Integrated TB Control in Central Asia.[127]

United Nations

International Decade for Action

From June 20-23 2018 the High-Level International Conference on the International Decade for Action 'Water for Sustainable Development' was held in Dushanbe, which discussed the upcoming decade for action with regards to water.[128] A second conference on the same subject was planned to be held in June 2020.[129]

Dushanbe process on Countering Terrorism and its Financing in Central Asia

On 16-17 May 2019 a high-level conference entitled Countering Terrorism and its Financing Through Illicit Drug Trafficking and Organized Crime was held in Dushanbe and attended by more than 50 countries. It passed the Dushanbe declaration, which put the primary responsibility for fighting terrorism onto national governments. Other topics, such as drug smuggling, were also discussed.[130]

Conference on Interaction and Confidence-Building Measures in Asia

On June 15 2019 the fifth summit of the Conference on Interaction and Confidence-Building Measures in Asia was held in Dushanbe. The Asian members of the organization discussed common interests on topics such as peace and security, terrorism, arms control, the Iran nuclear deal, poverty, economic development, and globalization.[131]

Notable people

- Farrukh Amonatov (born 1978), chess grandmaster

- Daniel Bar-Tal (born 1946), Israeli academic

- Gulsara Dadabayeva (born 1976), long distance runner

- Zuhur Habibullaev (born 1932), artist

- Malika Kalontarova (born 1950), dancer

- Jamshed Karimov (born 1940), Tajik prime minister

- Vladimir Landsman (born 1941), violinist

- Alexander Mironenko (born 1959), Hero of the Soviet Union

- Zarrina Mirshakar (born 1947), composer

- Shoista Mullojonova (born 1925), singer

- Dilshod Nazarov (born 1982), hammer thrower

- Tahmina Niyazova (born 1989), singer

- Vladimir Popovkin (born 1957), commander of Russian Space Forces

- Umarali Quvvatov (born 1968), opposition figure

- Gulrukhsor Safieva (born 1947), Iranologist

- Tolib Shakhidi (born 1946), composer

- Malika Sobirova (born 1942), ballet dancer

- Vladimir Voinovich (born 1932), Soviet dissident and writer

- Zafar Usmanov (born 1937), mathmetician

See also

References

- "About Dushanbe". U.S. Embassy in Tajikistan. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- https://www.stat.tj/en/publications

- "Sub-national HDI - Area Database - Global Data Lab". hdi.globaldatalab.org. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- "General information about Dushanbe". Conference on Interaction and Confidence-Building Measures in Asia. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

The village Dushanbe arose at the crossroads. On Mondays big Bazaar’s would be organized, which is where the village inherited its name "Dushanbe", meaning "Monday".

- D. Saimaddinov, S. D. Kholmatova, and S. Karimov, Tajik-Russian Dictionary, Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Tajikistan, Rudaki Institute of Language and Literature, Scientific Center for Persian-Tajik Culture, Dushanbe, 2006.

- "TAJIKISTAN". The World Factbook. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

etymology: today's city was originally at the crossroads where a large bazaar occurred on Mondays, hence the name Dushanbe, which in Persian means Monday, i.e., the second day (du) after Saturday (shambe)

- "Central Asia :: Tajikistan — The World Factbook - Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

- Dushanbe in Dictionary of Geographic Names (in Russian)

- Dushanbe in Persian language Archived 31 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Ranov, V. A. (Vadim Aleksandrovich) (1993). Dushanbe : gorod drevniĭ (PDF). Solovʹev, V. S. (Viktor Stepanovich), Masov, R. M. (Rakhim Masovich). Dushanbe: Izd-vo "Donish". p. 15. ISBN 5-8366-0427-4. OCLC 32311792.

- "Hissar Culture". TheFreeDictionary.com. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- Ranov, V. A. (Vadim Aleksandrovich) (1993). Dushanbe : gorod drevniĭ (PDF). Solovʹev, V. S. (Viktor Stepanovich), Masov, R. M. (Rakhim Masovich). Dushanbe: Izd-vo "Donish". pp. 21, 25. ISBN 5-8366-0427-4. OCLC 32311792.

- Ranov, V. A. (Vadim Aleksandrovich) (1993). Dushanbe : gorod drevniĭ (PDF). Solovʹev, V. S. (Viktor Stepanovich), Masov, R. M. (Rakhim Masovich). Dushanbe: Izd-vo "Donish". p. 100. ISBN 5-8366-0427-4. OCLC 32311792.

- Ranov, V. A. (Vadim Aleksandrovich) (1993). Dushanbe : gorod drevniĭ (PDF). Solovʹev, V. S. (Viktor Stepanovich), Masov, R. M. (Rakhim Masovich). Dushanbe: Izd-vo "Donish". pp. 107–108. ISBN 5-8366-0427-4. OCLC 32311792.

- Ranov, V. A. (Vadim Aleksandrovich) (1993). Dushanbe : gorod drevniĭ (PDF). Solovʹev, V. S. (Viktor Stepanovich), Masov, R. M. (Rakhim Masovich). Dushanbe: Izd-vo "Donish". p. 27. ISBN 5-8366-0427-4. OCLC 32311792.

- Yavan, Oxford Art Online. Macy, Laura Williams. [Basingstoke, England]: Macmillan. 2002. ISBN 1-884446-05-1. OCLC 50959350.CS1 maint: others (link)

- "Regions: Dushanbe & Surroundings". Official Website of the Tourism Authority of Tajikistan. Committee of Youth Affairs, Sports and Tourism. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- Ranov, V. A. (Vadim Aleksandrovich) (1993). Dushanbe : gorod drevniĭ (PDF). Solovʹev, V. S. (Viktor Stepanovich), Masov, R. M. (Rakhim Masovich). Dushanbe: Izd-vo "Donish". p. 110. ISBN 5-8366-0427-4. OCLC 32311792.

- "tajikistan". www.afc.ryukoku.ac.jp. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- Ranov, V. A. (Vadim Aleksandrovich) (1993). Dushanbe : gorod drevniĭ (PDF). Solovʹev, V. S. (Viktor Stepanovich), Masov, R. M. (Rakhim Masovich). Dushanbe: Izd-vo "Donish". pp. 125–126. ISBN 5-8366-0427-4. OCLC 32311792.

- Hiebert, F. T.; Kohl, P. L. (20 October 2012). "Garav kala: a Pleiades place resource". Pleiades: a gazetteer of past places. R. Talbert, T. Elliott, S. Gillies. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- Ranov, V. A. (Vadim Aleksandrovich) (1993). Dushanbe : gorod drevniĭ (PDF). Solovʹev, V. S. (Viktor Stepanovich), Masov, R. M. (Rakhim Masovich). Dushanbe: Izd-vo "Donish". pp. 38–39. ISBN 5-8366-0427-4. OCLC 32311792.

- 38-39

- "AJINA TEPE – Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- Ranov, V. A. (Vadim Aleksandrovich) (1993). Dushanbe : gorod drevniĭ (PDF). Solovʹev, V. S. (Viktor Stepanovich), Masov, R. M. (Rakhim Masovich). Dushanbe: Izd-vo "Donish". pp. 54–55, 85, 90. ISBN 5-8366-0427-4. OCLC 32311792.

- "Illustrations" (PDF). p. 3.

- Ranov, V. A. (Vadim Aleksandrovich) (1993). Dushanbe : gorod drevniĭ (PDF). Solovʹev, V. S. (Viktor Stepanovich), Masov, R. M. (Rakhim Masovich). Dushanbe: Izd-vo "Donish". p. 133. ISBN 5-8366-0427-4. OCLC 32311792.

- Ranov, V. A. (Vadim Aleksandrovich) (1993). Dushanbe : gorod drevniĭ (PDF). Solovʹev, V. S. (Viktor Stepanovich), Masov, R. M. (Rakhim Masovich). Dushanbe: Izd-vo "Donish". p. 136. ISBN 5-8366-0427-4. OCLC 32311792.

- Ranov, V. A. (Vadim Aleksandrovich) (1993). Dushanbe : gorod drevniĭ (PDF). Solovʹev, V. S. (Viktor Stepanovich), Masov, R. M. (Rakhim Masovich). Dushanbe: Izd-vo "Donish". p. 170. ISBN 5-8366-0427-4. OCLC 32311792.

- Ranov, V. A. (Vadim Aleksandrovich) (1993). Dushanbe : gorod drevniĭ (PDF). Solovʹev, V. S. (Viktor Stepanovich), Masov, R. M. (Rakhim Masovich). Dushanbe: Izd-vo "Donish". pp. 61, 144. ISBN 5-8366-0427-4. OCLC 32311792.

- Ranov, V. A. (Vadim Aleksandrovich) (1993). Dushanbe : gorod drevniĭ (PDF). Solovʹev, V. S. (Viktor Stepanovich), Masov, R. M. (Rakhim Masovich). Dushanbe: Izd-vo "Donish". p. 163. ISBN 5-8366-0427-4. OCLC 32311792.

- Ranov, V. A. (Vadim Aleksandrovich) (1993). Dushanbe : gorod drevniĭ (PDF). Solovʹev, V. S. (Viktor Stepanovich), Masov, R. M. (Rakhim Masovich). Dushanbe: Izd-vo "Donish". pp. 149–151. ISBN 5-8366-0427-4. OCLC 32311792.

- "Садои мардум — нашрияи Маҷлиси Олии Ҷумҳурии Тоҷикистон — АҶАБ ШАҲРИ ДИЛОРОЙӢ" (in Tajik). Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- Abdullaev, Kamoludin. (2018). "Dushanbe". Historical Dictionary of Tajikistan. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. pp. 130–131. ISBN 978-1-5381-0252-7. OCLC 1049912411.

- Rusu, Stefan; Dubovitskiy, Victor (2016). Spaces on the Run. Turkey. Istanbul: Dushanbe Art Ground. p. 31. ISBN 978-99947-892-7-6.

- "Аҷаб шаҳри дилороӣ, Душанбе…". tiroz.org (in Russian). 19 July 2019. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- "Краткая историческая справка". web.archive.org. 1 December 2008. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- "DUSHANBE – Encyclopaedia Iranica". iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- "«Русский дом», «Заразка» и «Детский садик» - истории инфекционных больниц Душанбе | Новости Таджикистана ASIA-Plus". asiaplustj.info. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- Вечёрка (9 July 2019). "Душанбе - столица края". Вечёрка (in Russian). Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- "A Tomb in Kabul: The Fate of the Last Amir of Bukhara and his country's relations with Afghanistan". Afghanistan Analysts Network - English (in Pashto). 27 December 2018. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- Bleuer, Christian. (2013). Tajkistan: A Political and Social History. ANU Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-1-925021-15-8. OCLC 1076650077.

- "A Tomb in Kabul: The Fate of the Last Amir of Bukhara and his country's relations with Afghanistan". Afghanistan Analysts Network - English (in Pashto). 27 December 2018. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- Projorov, A. M. 1916-2002. (1973–1982). "Dushanbe". Great Soviet encyclopedia. Macmillan. OCLC 435381348.CS1 maint: date format (link)

- "History". www.dushanbehotels.ru. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- "Dushanbe: History". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- "Бухарская Народная Советская Республика - это... Что такое Бухарская Народная Советская Республика?". Словари и энциклопедии на Академике (in Russian). Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- Bleuer, Christian. (2013). Tajkistan: A Political and Social History. Australian National University. p. 41. OCLC 940754059.

- Abdullaev, Kamoludin. (2018). "Chronology". Historical Dictionary of Tajikistan. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. pp. xxviii–xxxvi. ISBN 978-1-5381-0252-7. OCLC 1049912411.

- Times, Walter Duranty Wireless To the New York (23 October 1929). "TAJIKISTAN CAPITAL BECOMES STALINABAD; Change Follows Elevation to Soviet Federal State--Regime Starts by Declaring an Amnesty". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- "Чтобы помнили. Русский Душанбе". Фергана.Ру. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- Редакция. "Душанбе". Электронная еврейская энциклопедия ОРТ (in Russian). Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- Shermatov, Gafur. "Столица и ее градоначальники: кто был до Рустама Эмомали". Asia-Plus. Archived from the original on 13 February 2017.

- "Первый архитектор Душанбе. Кто спроектировал главную улицу таджикской столицы | Новости Таджикистана ASIA-Plus". asiaplustj.info. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- "Чтобы помнили. Русский Душанбе". Фергана.Ру. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- DeYoung, Alan J.; Kataeva, Zumrad; Jonbekova, Dilrabo (2018), Huisman, Jeroen; Smolentseva, Anna; Froumin, Isak (eds.), "Higher Education in Tajikistan: Institutional Landscape and Key Policy Developments", 25 Years of Transformations of Higher Education Systems in Post-Soviet Countries: Reform and Continuity, Palgrave Studies in Global Higher Education, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 363–385, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-52980-6_14, ISBN 978-3-319-52980-6, retrieved 1 August 2020

- "CIA Information Report" (PDF). CIA.

- "Дюшамбе - Сталинабад - Душанбе". Радио Озоди (in Russian). Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- "H-Diplo Roundtable XX-46 on Laboratory of Socialist Development: Cold War Politics and Decolonization in Soviet Tajikistan | H-Diplo | H-Net". networks.h-net.org. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- "Perspectives | Light and nostalgia in Tajikistan | Eurasianet". eurasianet.org. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- Nourzhanov, Kirill, aut. (2013). Tajikistan a political and social history. ANU E Press. p. 156. ISBN 978-1-925021-16-5. OCLC 984803513.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Nourzhanov, Kirill, aut. (2013). Tajikistan a political and social history. ANU E Press. pp. 180–183. ISBN 978-1-925021-16-5. OCLC 984803513.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Ethnic rioting in Dushanbe, New York Times, 13 February 1990. Retrieved 18 October 2008

- Nourzhanov, Kirill, aut. (2013). "The Rise of Opposition, the Contraction of the State and the Road to Independence". Tajikistan a political and social history. ANU E Press. ISBN 978-1-925021-16-5. OCLC 984803513.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Bleuer, Christian. (2013). "Epilogue: The Civil War of 1992". Tajkistan: A Political and Social History. ANU Press. pp. 327–329. ISBN 978-1-925021-15-8. OCLC 1076650077.

- Refugees, United Nations High Commissioner for. "Refworld | Chronology for Russians in Tajikistan". Refworld. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- "The long echo of Tajikistan's civil war". openDemocracy. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- "Tajikistan and UNESCO Cooperation". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Tajikistan. 05/11/2019. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - "Analysis: Dushanbe's Ex-Mayor One Of The Last Of Civil War Era". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- "Tajikistan: regime eternalization completed?". The Politicon. The Politicon. 26 January 2017. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

- "Updated Asian map of the Köppen climate classification system".

- "Tajikistan: Citizens Ponder Bleak Future Amid Harsh Winter - Eurasianet.Org". Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 22 August 2013.

- "Klimatafel von Duschanbe / Tadschikistan" (PDF). Baseline climate means (1961–1990) from stations all over the world (in German). Deutscher Wetterdienst. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

- "Dushanbe Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

- "/ Исполнительный орган государственной власти города Душанбе". www.dushanbe.tj. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- "Тақсимоти маъмурӣ / Сомонаи расмии Мақомоти иҷроияи ҳокимияти давлатии шаҳри Душанбе". www.dushanbe.tj. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- "About Dushanbe". U.S. Embassy in Tajikistan. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- "Tallest unsupported flagpole". Guinness World Records. 24 May 2011. Retrieved 14 December 2011.

- "Dushanbe travel guide". Caravanistan. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

- https://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/10603/14505/11/11_chapter%203.pdf p. 116

- "CensusInfo - Data". www.censusinfo.tj. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- Genesis 1987, USSR

- Matveeva, Anna. (2009). The perils of emerging statehood : civil war and state reconstruction in Tajikistan : an analytical narrative. Crisis States Research Centre. p. 5. OCLC 436344566.

- "Population of the Republic of Tajikistan as of January 1, 2020". Agency on Statistics of the Republic of Tajikistan.

- https://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/bitstream/10603/14505/11/11_chapter%203.pdf p. 92

- Population of the Republic of Tajikistan as of 1 January, State Statistical Committee, Dushanbe, 2008 (Russian)

- "Tajikistan: Provinces, Major Cities & Urban Settlements - Population Statistics, Maps, Charts, Weather and Web Information". www.citypopulation.de.

- "Шумораи аҳолии Ҷумҳурии Тоҷикистон то 1 январи соли 2016 Ахбороти Агентии омори назди Президенти Ҷумҳурии Тоҷикистон" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 August 2017. Retrieved 22 July 2017.

- "Все началось с полета Бухара - Душанбе: развитие авиации Таджикистана". Sputnik Таджикистан (in Russian). Retrieved 4 August 2020.

- "Directory: World Airlines." Flight International. 30 March-5 April 2004. 78. "Titov Street 31/2, Dushanbe Airport, Dushanbe, 734006, Tajikistan."

- "Contacts Archived 29 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine." Somon Air. Retrieved on 4 December 2010. "Contacts: 40, Titova Str. Dushanbe, Tajikistan, 734012." Address in Tajik : "734012, Таджикистан, Душанбе, ул. Титова, 40"

- "Япония потратит $3,9 миллиона на модернизацию аэропорта в Душанбе". Sputnik Таджикистан (in Russian). Retrieved 4 August 2020.

- "Наследие Российской империи в Таджикистане: железная дорога, вокзалы, водонапорные башни". Фергана.Ру. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- Abdullaev, Kamoludin. (2018). "Railways". Historical Dictionary of Tajikistan. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 364. ISBN 978-1-5381-0252-7. OCLC 1049912411.

- "Дорога через века - Транспортная газета ЕВРАЗИЯ ВЕСТИ". eav.ru. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- Migrant Express Part 1: Good-bye Dushanbe, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BBSardpSH0E

- "Dushanbe-Astana Train Makes First Journey". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- "КАвЗ: в будущее - с оптимизмом". web.archive.org. 16 April 2012. Retrieved 4 August 2020.

- "Demolishing Dushanbe: how the former city of Stalinabad is erasing its Soviet past". The Guardian. 19 October 2017. Retrieved 7 November 2019.

- 2020-01-27T06:00:00+00:00. "EBRD finances Dushanbe trolleybus infrastructure modernisation". Railway Gazette International. Retrieved 4 August 2020.

- "Toward safer, cleaner, and more convenient public transport in Central Asian cities". blogs.worldbank.org. Retrieved 4 August 2020.

- "Dushanbe, trolleybus — Roster". transphoto.org. Retrieved 4 August 2020.

- "Subway system expected to be built in Tajik capital by 2040". Asia plus.

- "Envoy: Iran to complete Tajikistan's independence tunnel by next year". The Iran Project. 8 May 2014. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- "2.3 Tajikistan Road Network - Logistics Capacity Assessment - Digital Logistics Capacity Assessments". dlca.logcluster.org. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- Shar-Shar auto tunnel links Tajikistan to China, The 2.3 km (1 mi) Shar-Shar car tunnel linking Tajikistan and China opened to traffic on Aug. 30., Siyavush Mekhtan, 2009-09-03, http://centralasiaonline.com/en_GB/articles/caii/features/2009/09/03/feature-06

- Chormaghzak Tunnel renamed Khatlon Tunnel and Shar-Shar Tunnel renamed Ozodi Tunnel, 12/02/2014 15:49, Payrav Chorshanbiyev, http://news.tj/en/news/chormaghzak-tunnel-renamed-khatlon-tunnel-and-shar-shar-tunnel-renamed-ozodi-tunnel Archived 31 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- "Opera as the highest stage of Socialism | IIAS". www.iias.asia. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- "ТАДЖИКСКИЙ ТЕАТР ОПЕРЫ И БАЛЕТА в музыкальной энциклопедии". www.music-dic.ru. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- "История театра". ТЕАТР ОПЕРЫ И БАЛЕТА (in Russian). Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- "istoriya-teatra". web.archive.org. 11 December 2016. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- "Таджикский театр оперы и балета им. С.Айни". Кино-Театр.РУ. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- "Festive event dedicated to the Day of Tajik Militia (video)". mvd.tj. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- Abazov, Rafis. (2006). Tajikistan. Marshall Cavendish Benchmark. p. 109. ISBN 0-7614-2012-6. OCLC 859079567.

- "Tajikistan honors Iranian conductor Arash Amini". Tehran Times. 20 November 2011. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- "State Symphony orchestra will be created in Tajikistan | Tajikistan News ASIA-Plus". www.asiaplustj.info. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- "The first performance of the State Symphony orchestra of Tajikistan will be held on the 9th of September | Tajikistan News ASIA-Plus". asiaplustj.info. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- "Ayni Academic Opera and Ballet Theater". www.dushanbehotels.ru. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- "Ayni Opera & Ballet Theatre | Dushanbe, Tajikistan Entertainment". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- Mulloev, Sharif (2009). Usmonov; Chigrin (eds.). История таджикской журналистики: учебно-методическое пособие для студентов отделения журналистики [History of Tajik journalism: a textbook for students of journalism.]. Dushanbe: Russian-Tajik (Slavic) University - Department of History and Theory of Journalism and Electronic Media.

- "In Russia, unknown attacker stabs exiled Tajik journalist". Committee to Protect Journalists. 13 January 2012. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- "AN OVERVIEW OF THE MEDIA IN TAJIKISTAN". www.hrw.org. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- "Twin-cities of Azerbaijan". Azerbaijans.com. Retrieved 9 August 2013.

- "Dushanbe mayor invites mayors of 17 sister cities of Tajik capital for celebration of Navrouz in Dushanbe | Tajikistan News ASIA-Plus". asiaplustj.info. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- "Tajik capital and China's Hainan become sister cities". Trend.Az. 13 December 2018. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- "Boulder Dushanbe Sister Cities". Boulder-Dushanbe Sis. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- "USAID and Ministry of Health Hold Third International Conference on Integrated TB Control in Central Asia". U.S. Embassy in Tajikistan. 13 September 2018. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- ""Water for Sustainable Development" Conference in Dushanbe". UNRCCA. 23 June 2018. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- ""Dushanbe water process ". Second High-Level Conference on the International Decade for action "Water for Sustainable Development", 2018-2028,". Embassy of the Republic of Tajikistan in Germany.

- "UNRCCA AND UNOCT PARTICIPATED IN THE HIGH-LEVEL CONFERENCE "COUNTERING TERRORISM AND ITS FINANCING THROUGH ILLICIT DRUG TRAFFICKING AND ORGANIZED CRIME" IN DUSHANBE, 16-17 MAY 2019". UNRCCA. 20 May 2019. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- "CICA members call for sustainable security, development in Asia - Xinhua | English.news.cn". www.xinhuanet.com. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dushanbe. |

- Pictures of Dushanbe

- Dushanbe pictures through eyes of westerner

- Tajik Web Gateway

- Boulder-Dushanbe Sister Cities

- Dushanbe – TimeLapse

%2C_Emir_of_Bukhara%2C_photographed_by_S.M._Prokudin-Gorskiy_in_1911.jpg)

.jpg)