Balkh

Balkh (/bælx/; Pashto and Persian: بلخ, Balkh; Ancient Greek: Βάκτρα, Báktra; Bactrian: Βάχλο, Bakhlo) is a town in the Balkh Province of Afghanistan, about 20 km (12 mi) northwest of the provincial capital, Mazar-e Sharif, and some 74 km (46 mi) south of the Amu Darya river and the Uzbekistan border. It was historically an ancient centre of Buddhism, Islam, and Zoroastrianism and one of the major cities of Khorasan, since the latter's earliest history.

Balkh بلخ Βάχλο | |

|---|---|

| |

Balkh Location in Afghanistan | |

| Coordinates: | |

| Country | |

| Province | Balkh Province |

| District | Balkh District |

| Elevation | 1,198 ft (365 m) |

| Population (2006) | |

| • City | 77,000 |

| Time zone | + 4.30 |

| Climate | BSk |

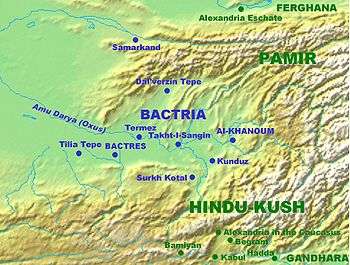

The ancient city of Balkh was known to the Ancient Greeks as Bactra, giving its name to Bactria. It was mostly known as the centre and capital of Bactria or Tokharistan. Marco Polo described Balkh as a "noble and great city".[3] Balkh is now for the most part a mass of ruins, situated some 12 km (7.5 mi) from the right bank of the seasonally flowing Balkh River, at an elevation of about 365 m (1,198 ft).

French Buddhist Alexandra David-Néel associated Shambhala with Balkh, also offering the Persian Sham-i-Bala ("elevated candle") as an etymology of its name.[4] In a similar vein, the Gurdjieffian J. G. Bennett published speculation that Shambalha was Shams-i-Balkh, a Bactrian sun temple.[5]

Etymology

The Bactrian language name of the city was βαχλο. In Middle Persian texts was named Baxl (Middle Persian: 𐭡𐭠𐭧𐭫). The name of the province or country also appears in the Old Persian inscriptions (B.h.i 16; Dar Pers e.16; Nr. a.23) as Bāxtri, i.e. Bakhtri (Old Persian: 𐎲𐎠𐎧𐎫𐎼𐎡𐏁). It is written in the Avesta as Bāxδi (Avestan: 𐬠𐬁𐬑𐬜𐬌) . From this came the intermediate form Bāxli, Sanskrit Bahlīka (also Balhika) for "Bactrian", and by transposition the modern Persian Balx, i.e. Balkh, and Armenian Bahl.[6]

History

Balkh is considered to be the first city to which the Indo-Iranian tribes moved from north of the Amu Darya, between 2000 and 1500 BC.[7] The Arabs called it Umm Al-Bilad or Mother of Cities on account of its antiquity. The city was traditionally a center of Zoroastrianism.[8] The name Zariaspa, which is either an alternate name for Balkh or a term for part of the city, may derive from the important Zoroastrian fire temple Azar-i-Asp.[8] Balkh was regarded as the place where Zoroaster first preached his religion, as well as the place where he died.

Since the Indo-Iranians built their first kingdom in Balkh[9] (Bactria, Daxia, Bukhdi) some scholars believe that it was from this area that different waves of Indo-Iranians spread to north-east Iran and Seistan region, where they, in part, became today's Persians, Tajiks, Pashtuns and Baluch people of the region. The changing climate has led to desertification since antiquity, when the region was very fertile. Its foundation is mythically ascribed to Keyumars, the first king of the world in Persian legend; and it is at least certain that, at a very early date, it was the rival of Ecbatana, Nineveh and Babylon.

For a long time the city and country was the central seat of the dualistic Zoroastrian religion, the founder of which, Zoroaster, died within the walls according to the Persian poet Firdowsi. Armenian sources state that the Arsacid Dynasty of the Parthian Empire established its capital in Balkh. There is a long-standing tradition that an ancient shrine of Anahita was to be found here, a temple so rich it invited plunder. Alexander the Great married Roxana of Bactria after killing the king of Balkh.[10] The city was the capital of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom and was besieged for three years by the Seleucid Empire (208–206 BC). After the demise of the Greco-Bactrian kingdom, it was ruled by Indo-Scythians, Parthians, Indo-Parthians, Kushan Empire, Indo-Sassanids, Kidarites, Hephthalite Empire and Sassanid Persians before the arrival of the Arabs.

Bactrian religion

Bactrian documents - in the Bactrian language, written from the fourth to eighth centuries - consistently evoke the name of local deities, such as Kamird and Wakhsh, for example, as witnesses to contracts. The documents come from an area between Balkh and Bamiyan, which is part of Bactria.[11]

Buddhism

Balkh town is well known to Buddhist countries because of two great Buddhist monks of Afghanistan – Trapusa and Bahalika. There are two stupas over their relics. According to a popular legend, Buddhism was introduced in Balkh by Bhallika, disciple of Buddha, and the city derives its name from him. He was a merchant of the region and had come from Bodhgaya. In literature, Balkh has been described as Balhika, Valhika or Bahlika. First Vihara at Balkh was built for Bhallika when he returned home after becoming a Buddhist monk. Xuanzang visited Balkh in 630 when it was a flourishing centre of Hinayana Buddhism.

According to the Memoirs of Xuanzang, there were about a hundred Buddhist convents in the city or its vicinity at the time of his visit there in the 7th century. There were 3,000 monks and a large number of stupas and other religious monuments. The most remarkable stupa was the Navbahara (Sanskrit, Nav Vihara: New Monastery), which possessed a gigantic statue of Buddha. Shortly before the Arab conquest, the monastery became a Zoroastrian fire-temple. A curious reference to this building is found in the writings of the geographer Ibn Hawqal, an Arab traveller of the 10th century, who describes Balkh as built of clay, with ramparts and six gates, and extending for half a parasang. He also mentions a castle and a mosque.

A Chinese pilgrim, Fa-Hein, (c.400) found Hinayana practice prevalent in Shan Shan, Kucha, Kashgar, Osh, Udayana and Gandhara. Xuanzang remarked that Buddhism was widely practised by the Hunnish rulers of Balkh, who descended from Indian royal stock.[12]

A Korean monk, Huichao, noted as late as the eighth century after the Arab invasion that the residents of Balkh practiced Buddhism and followed a Buddhist king. He noted the Arab invasion and that the king of Balkh at the time had fled to nearby Badakshan.[13]

Furthermore, we know that a number of Buddhist religious centres flourished in Khorasan. The most important was the Nawbahar (New Temple) near the town of Balkh, which evidently served as a pilgrimage centre for political leaders who came from far and wide to pay homage to it.[14]

A large number of Sanskrit medical, pharmacological toxicological texts were translated into Arabic under the patronage of Khalid, the vizier of Al-Mansur. Khalid was the son of a chief priest of a Buddhist monastery. Some of the family were killed when the Arabs captured Balkh; others including Khalid survived by converting to Islam. They were to be known as the Barmikis of Baghdad.[15]

Judaism

An ancient Jewish community existed in Balkh as recorded by the Arab historian Al-Maqrizi who wrote that the community was established by the transfer of Jews to Balkh by the Assyrian King Sennacherib. A Bāb al-Yahūd (Gate of Jews) and al-Yahūdiyya (Jewish town) in Balkh is attested to by Arab geographers.[16] Muslim tradition stated that the prophet Jeremiah fled to Balkh and that Ezekiel was buried there.[17]

This Jewish community was noted in the eleventh century as the Jews of the city were forced to maintain a garden for the Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni for which they paid a tax of 500 dirhems. According to Jewish oral history, Timur gave the Jews of Balkh a city quarter of their own with a gate to close it.[18]

The Jewish community in Balkh was reported as late as the nineteenth century where Jews still resided in a special quarter of the city.[19]

The famed Jewish exegete Hiwi al-Balkhi was from Balkh.

Arab Conquest

At the time of the Islamic conquest of Persia in the 7th century, however, Balkh had provided an outpost of resistance and a safe haven for the Persian emperor Yazdegerd III who fled there from the armies of Umar. Later, in the 9th century, during the reign of Ya'qub bin Laith as-Saffar, Islam became firmly rooted in the local population.

Arabs occupied Persia in 642 (during the Caliphate of Uthman, 644–656 AD). Attracted by the grandeur and wealth of Balkh, they attacked it in 645 AD. It was only in 653 when Arab commander al-Ahnaf raided the town again and compelled it to pay tribute. The Arab hold over the town, however, remained tenuous. The area was brought under Arab control only after it was reconquered by Muawiya in 663 AD. Prof. Upasak describes the effect of this conquest in these words: "The Arabs plundered the town and killed the people indiscriminately. It is said that they raided the famous Buddhist shrine of Nava-Vihara, which the Arab historians call 'Nava Bahara' and describe it as one of the magnificent places, which comprised a range of 360 cells around the high stupas'. They plundered the gems and jewels that were studded on many images and stupas and took away the wealth accumulated in the Vihara but probably did no considerable harm to other monastic buildings or to the monks residing there".

The Arab attacks had little effect on the normal ecclesiastical life in the monasteries or Balkh Buddhist population outside. Buddhism continued to flourish with their monasteries as the centres of Buddhist learning and training. Scholars, monks and pilgrims from China, India and Korea continued to visit this place.

Several revolts were made against the Arab rule in Balkh.

The Arabs' control over Balkh did not last long as it soon came under the rule of a local prince, a zealous Buddhist called Nazak (or Nizak) Tarkhan. He expelled the Arabs from his territories in 670 or 671. He is said to have not only reprimanded the Chief Priest (Barmak) of Nava-Vihara but beheaded him for embracing Islam. As per another account, when Balkh was conquered by the Arabs, the head priest of the Nava-Vihara had gone to the capital and became a Muslim. This displeased the people of the Balkh. He was deposed and his son was placed in his position.

Nazak Tarkhan is also said to have murdered not only the Chief Priest but also his sons. Only a young son was saved. He was taken by his mother to Kashmir where he was given training in medicine, astronomy and other sciences. Later they returned to Balkh. Prof. Maqbool Ahmed observes "One is tempted to think that the family originated from Kashmir, for in time of distress, they took refuge in the Valley. Whatever it be, their Kashmiri origin is undoubted and this also explains the deep interest of the Barmaks, in later years, in Kashmir, for we know they were responsible for inviting several scholars and physicians from Kashmir to the Court of Abbasids." Prof. Maqbool also refers to the descriptions of Kashmir contained in the report prepared by the envoy of Yahya bin Barmak. He surmises that the envoy could have possibly visited Kashmir during the reign of Samgramapida II (797–801). Reference has been made to sages and arts.

The Arabs managed to bring Balkh under their control only in 715 AD, in spite of strong resistance offered by the Balkh people during the Umayyad period. Qutayba ibn Muslim al-Bahili, an Arab General was Governor of Khurasan and the east from 705 to 715. He established a firm hold over lands beyond the Oxus for the Arabs. He fought and killed Tarkhan Nizak in Tokharistan (Bactria) in 715. In the wake of Arab conquest, the resident monks of the Vihara were either killed or forced to abandon their faith. The Viharas were razed to the ground. Priceless treasures in the form of manuscripts in the libraries of monasteries were consigned to ashes. Presently, only the ancient wall of the town, which once encircled it, stands partially. Nava-Vihara stands in ruins, near Takhta-i-Rustam.[20] In 726, the Umayyad governor Asad ibn Abdallah al-Qasri rebuilt Balkh and installed in it an Arab garrison,[21] while in his second governorship, a decade later, he transferred the provincial capital there.[22]

The Umayyad period lasted until 747, when Abu Muslim captured it for the Abbasids (next Sunni Caliphate dynasty) during the Abbasid Revolution. The city remained in Abbasid hands until 821, when it was taken over by the Tahirid dynasty, albeit still in the Abbasids' name. In 870, the Saffarids captured it.

From Saffarids to Khwarezmshahs

In 870, Ya'qub ibn al-Layth al-Saffar rebelled against Abbasid rule and founded the Saffarid dynasty at Sistan. He captured present Afghanistan and most of present Iran. His successor Amr ibn al-Layth, tried to capture Transoxiana from the Samanids, who were nominally vassals of Abbasids, but he was defeated and captured by Ismail Samani at Battle of Balkh in 900. He was sent to the Abbasid Caliph as a prisoner and was executed in 902. The power of Saffarids was diminished and they became vassals of the Samanids. Thus Balkh now passed to them.

Samanid rule in Balkh lasted until 997, when their former subordinates, the Ghaznavids, captured it. In 1006, Balkh was captured by Karakhanids, but Ghaznavids recaptured it 1008. Finally, the Seljuks (Turks) conquered Balkh in 1059. In 1115, it was occupied and looted by irregular Oghuz Turks. Between 1141 and 1142, Balkh was captured by Atsiz, Shah of Khwarezm, after the Seljuks were defeated by the Kara-Khitan Khanate at the Battle of Qatwan. Ahmad Sanjar decisively defeated a Ghurid army, commanded by Ala al-Din Husayn and he took him prisoner for two years before releasing him as a vassal of the Seljuks. The next year, he marched against rebellious Oghuz Turks from Khuttal and Tukharistan. But he was defeated twice and was captured after a second battle in Merv. The Oghuzs looted Khorasan after their victory.

Balkh was nominally ruled by Mahmud Khan, the former khan of Western Karakhanids, but the real power was held by Muayyid al-Din Ay Aba, amir of Nishabur for three years. Sanjar finally escaped from captivity and returned to Merv through Termez. He died in 1157 and control of Balkh passed to Mahmud Khan until his death in 1162. It was captured by Khwarezmshahs in 1162, by the Kara Khitans in 1165, by the Ghurids in 1198 and again by Khwarezmshahs in 1206.

Muhammad al-Idrisi, in the 12th century, speaks of its possessing a variety of educational establishments, and carrying on an active trade. There were several important commercial routes from the city, stretching as far east as India and China. The late 12th-century local chronicle The Merits of Balkh (Fada'il-i-Balkh), by Abu Bakr Abdullah al-Wa'iz al-Balkhi, states that a woman known only as the khatun (lady) of Davud, from 848 appointed governor of Balkh, had taken over from him with "particular responsibility for the city and people" while he was busy building himself an elaborate pleasure palace called Nawshǎd (New Joy).[23]

Mongol invasion

In 1220 Genghis Khan sacked Balkh, butchered its inhabitants and levelled all the buildings capable of defence – treatment to which it was again subjected in the 14th century by Timur. Notwithstanding this, however, Marco Polo (probably referring to its past) could still describe it as "a noble city and a great seat of learning." For when Ibn Battuta visited Balkh around 1333 during the rule of the Kartids, who were Tadjik vassals of the Persia-based Mongol Ilkhanate until 1335, he described it as a city still in ruins: "It is completely dilapidated and uninhabited, but anyone seeing it would think it to be inhabited because of the solidity of its construction (for it was a vast and important city), and its mosques and colleges preserve their outward appearance even now, with the inscriptions on their buildings incised with lapis-blue paints."[24]

It was not reconstructed until 1338. It was captured by Tamerlane in 1389 and its citadel was destroyed, but Shah Rukh, his successor, rebuilt the citadel in 1407.

16th to 19th centuries

In 1506 Uzbeks entered Balkh under the command of Muhammad Shaybani. They were briefly expelled by the Safavids in 1510. Babur ruled Balkh between 1511 and 1512 as a vassal of the Persian Safavids. But he was defeated twice by the Khanate of Bukhara and was forced to retire to Kabul. Balkh was ruled by Bukhara except for Safavid rule between 1598 and 1601.

The Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan fruitlessly fought them there for several years in the 1640s. Nevertheless, Balkh was ruled by the Mughal Empire from 1641 and turned into a subah (imperial top-level province) in 1646 by Shah Jahan, only to be lost in 1647, just like the neighboring Badakhshan Subah. Balkh was the government seat of Aurangzeb in his youth. In 1736 it was conquered by Nader Shah. After his assassination, local Uzbek Hadji Khan declared the independence of Balkh in 1747, but he submitted to Bukhara in 1748.

Under the Durani monarchy it fell into the hands of the Afghans in 1752. Bukhara regained it in 1793. It was conquered by Shah Murad of Kunduz in 1826, and for some time was subject to the Emirate of Bukhara. In 1850, Dost Mohammad Khan, the Emir of Afghanistan, captured Balkh, and from that time it remained under Afghan rule.[25] In 1866, after a malaria outbreak during the flood season, Balkh lost its administrative status to the neighbouring city of Mazar-i-Sharif (Mazār-e Šarīf).[26][27]

20th to 21st centuries

In 1911 Balkh comprised a settlement of about 500 houses of Afghan settlers, a colony of Jews and a small bazaar set in the midst of a waste of ruins and acres of debris. Entering by the west (Akcha) gate, one passed under three arches, in which the compilers recognized the remnants of the former Jama Masjid (Persian: جَامع مَسجد, romanized: Jama‘ Masjid, Friday Mosque).[28] The outer walls, mostly in utter disrepair, were estimated about 6.5–7 mi (10.5–11.3 km) in perimeter. In the south-east, they were set high on a mound or rampart, which indicated a Mongol origin to the compilers.

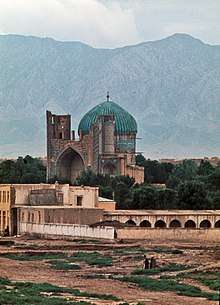

The fort and citadel to the north-east were built well above the town on a barren mound and were walled and moated. There was, however, little left of them but the remains of a few pillars. The Green Mosque (Persian: مَسجد سَبز, romanized: Masjid Sabz),[1][2] named for its green-tiled dome (see photograph top right corner) and said to be the tomb of the Khwaja Abu Nasr Parsa, had nothing but the arched entrance remaining of the former madrasah (Arabic: مَـدْرَسَـة, school).

The town was garrisoned as of 1911 by a few thousand irregulars (kasidars), the regular troops of Afghan Turkestan being cantoned at Takhtapul, near Mazari Sharif. The gardens to the north-east contained a caravanserai that formed one side of a courtyard, which was shaded by a group of chenar trees Platanus orientalis.[29]

A project of modernization was undertaken in 1934, in which eight streets were laid out, housing and bazaars built. Modern Balkh is a centre of the cotton industry, of the skins known commonly in the West as "Persian lamb" (Karakul), and for agricultural produce like almonds and melons.

The site and the museum have suffered from looting and uncontrolled digging during the 1990s civil war. After the Taliban's fall in 2001 some poor residents dug in an attempt to sell ancient treasures. The provisional Afghan government said in January 2002 that it had stopped the looting.[30]

Main sights

Ancient ruins of Balkh

The earlier Buddhist constructions have proved more durable than the Islamic buildings. The Top-Rustam is 46 m (50 yd) in diameter at the base and 27 m (30 yd) at the top, circular and about 15 m (49 ft) high. Four circular vaults are sunk in the interior and four passages have been pierced below from the outside, which probably lead to them. The base of the building is constructed of sun-dried bricks about 60 cm (2.0 ft) square and 100 to 130 mm (3.9 to 5.1 in) thick. The Takht-e Rustam is wedge-shaped in plan with uneven sides. It is apparently built of pisé mud (i.e. mud mixed with straw and puddled). It is possible that in these ruins we may recognize the Nava Vihara described by the Chinese traveller Xuanzang. There are the remains of many other topes (or stupas) in the neighbourhood.[31]

The mounds of ruins on the road to Mazar-e Sharif probably represent the site of a city yet older than those on which stands the modern Balkh.

Others

Numerous places of interest are to be seen today aside from the ancient ruins and fortifications:

- The madrasa of Sayed Subhan Quli Khan.

- Bala-Hesar, the shrine and mosque of Khwaja Nasr Parsa.

- The tomb of the poet Rabi'a Balkhi.

- The Nine Domes Mosque (Masjid-e Noh Gonbad). This exquisitely ornamented mosque, also referred to as Haji Piyada, is the earliest Islamic monument yet identified in Afghanistan.

- Tepe Rustam and Takht-e Rustam

Balkh Museum

The museum was formerly the second largest museum in the country, but its collection has suffered from looting in recent times.[32]

The museum is also known as the Museum of the Blue Mosque, from the building it shares with a religious library. As well as exhibits from the ancient ruins of Balkh, the collection includes works of Islamic art including a 13th-century Quran, and examples of Afghan decorative and folk art.

Cultural role

Balkh had a major role in the development of the Persian language and literature. The early works of Persian literature were written by poets and writers who were originally from Balkh.

Many famous Persian poets came from Balkh, e.g.:

- Mawlānā Jalal ad-Din Balkhi, born in Balkh, in the 13th century[33]

- Amir Khusraw Dehlavi, whose father, Amir Saifuddin, was from here

- Manuchihri Damghani, born in Balkh, according to Dawlat Shah Samarkandi

- Rashidudin Watwat, poet

- Sanih Balkhi, poet

- Shaheed Balkhi, Abul Muwayed Balkhi, Abu Shukur Balkhi, Ma'roofi Balkhi, early poets of the 9th or 10th centuries

- Rabi'a Balkhi, first woman poet in the history of Persian poetry, lived in the 10th century

- Avicenna or Ibn Sina, 10th century philosopher and scientist whose father was a Balkh native

- Unsuri Balkhi, 10th or 11th century poet

- Anvari, 12th century, lived and died in Balkh

- Daqiqi Balkhi, Abu Mansur Muhammad Ibn Ahmad Daqiqi Balkhi, born here

Other notable people

- Ibrahim ibn Adham, a Sufi saint and reputedly ruler of Balkh

- Khalid ibn Barmak, wazir of the Abbasid Caliphate and member of the prominent Barmakid family

- Abu Zayd al-Balkhi, Persian (850–934), polymath: geographer, mathematician, physician, psychologist and scientist

- Abu Ma'shar al-Balkhi, astrologer and astronomer at the Abbasid court, Islamic philosopher

- Hiwi al-Balkhi, Bukharan Jewish exegete and Biblical critic

- Abu-Shakur Balkhi (915–?), Persian poet

- Ibn Balkhi, a conventional name for a 12th-century Iranian historian and author of the Persian book Fārs-Nāma

- Abdullah, father of Avicenna and respected Ismaili scholar[34][35]

See also

- The Bahlikas

- Balhae

- Hiwi al-Balkhi

- The Barmakids, who were from that city.

- Kumargah

- Mount Imeon

- Vishtaspa

- Roxana

- Silk Road transmission of Buddhism

- Balkh Province

References

- "11 of the Most Ancient and Continually Occupied Cities in the World". Ancient Origins. 2018-01-31. Retrieved 2018-05-15.

- "Green Mosque, Balkh, Afghanistan". Muslim Mosques. Retrieved 2018-05-15.

- "City of Balkh (antique Bactria)". UNESCO World Heritage Centre.

- David-Néel, A. Les Nouvelles littéraires;1954, p.1

- Bennett, J. G., Gurdjieff: aking a New World Bennett notes Idries Shah as the source of the suggestion.

- Daniel Coit Gilman, Harry Thurston Peck and Frank Moore Colby (1902), The New International Encyclopædia, 2, Dodd, Mead & Co., p. 341CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Nancy Hatch Dupree, An Historical Guide to Afghanistan, 1977, Kabul, Afghanistan

- The Greeks in Bactria and India. William Woodthorpe Tarn. 1st Edition, 1938; 2nd Updated Edition, 1951. 3rd Edition, updated with a Preface and a new bibliography by Frank Lee Holt. Ares Publishers, Inc., Chicago. 1984. (1984), pp. 114–115 and n. 1.

- "IRAN vi. IRANIAN LANGUAGES AND SCRIPTS (1) E – Encyclopaedia Iranica". Retrieved 2 June 2015.

- Lynne O'Donnell (20 October 2013). "Silk Road jewel reveals more of its treasures". BBC News Magazine. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- Azad, A. (2013). Sacred Landscape in Medieval Afghanistan: Revisiting the Faḍāʾil-i Balkh. OUP.

- Buddhism in Central Asia by Baij Nath Puri, Motilal Banarsi Dass Publishers, Page 130

- van Bladel, Kevin (2011). "The Bactrian Background of the Barmakids". In A. Akasoy, C. Burnett and R. Yoeli-Tlalim (ed.). Islam and Tibet: Interactions along the Musk Routes. London: Ashgate. pp. 43–88.

- Reinterpreting Islamic Historiography: Hārūn al-Rashīd and the narrative of the ʻAbbāsid caliphate by Tayeb El-Hibri published by Cambridge University Press, 1999 Page 8 ISBN 0-521-65023-2, ISBN 978-0-521-65023-6

- India, the Ancient Past: a history of the Indian sub-continent from c. 7000 BC to AD 1200 by Burjor Avari Edition: illustrated Published by Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0-415-35616-4, ISBN 978-0-415-35616-9 Page 220.

- Ben Zion Yehoshua-Raz (2010). Stillman, Norman (ed.). Encyclopedia of Jews in the Islamic World. Brill Publishing.

- Fischel (1971). Encyclopedia Judaica (4 ed.). p. 147.

- Shterenshis, Michael (2013). Tamerlane and the Jews. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis. p. 58. ISBN 113687366X.

- Vladimirovich Barthold, Vasilii; Soucek, Sivat (2014). An Historical Geography of Iran. Princeton University Press. pp. 13–14. ISBN 0691612072.

- Kumar, Ramesh. "The Rise Of Barmarks". Kashmir News Network.

- Blankinship, Khalid Yahya, ed. (1989). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume XXV: The End of Expansion: The Caliphate of Hishām, A.D. 724–738/A.H. 105–120. SUNY Series in Near Eastern Studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. pp. 26–27. ISBN 978-0-88706-569-9.

- Blankinship, Khalid Yahya, ed. (1989). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume XXV: The End of Expansion: The Caliphate of Hishām, A.D. 724–738/A.H. 105–120. SUNY Series in Near Eastern Studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-88706-569-9.

- Arezou Azad: "Islam's forgotten scholars", History Today, Vol. 66, No. 10 (October 2016), p. 27.

- Gibb, H.A.R. trans. and ed. (1971). The Travels of Ibn Baṭṭūṭa, A.D. 1325–1354 (Volume 3). London: Hakluyt Society. p. 571.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- "Persia, Arabia, etc". World Digital Library. 1852. Retrieved 2013-07-27.

- Grenet, F. "BALḴ". Encyclopædia Iranica (Online ed.). United States: Columbia University. Archived from the original on 2018-11-17. Retrieved 2019-02-25.

- Cox, F. E. (October 2002). "History of Human Parasitology". Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 15: 595–612. doi:10.1128/cmr.15.4.595-612.2002. PMC 126866. PMID 12364371.

- "Balkh", The UNESCO, retrieved 2018-05-15

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- "Ancient Afghan City Looted Anew", The Art Newspaper, January 17, 2002, archived from the original on 2005-03-21

- Azad, Arezou (12 December 2013). Sacred Landscape in Medieval Afghanistan Revisiting the Faḍāʾil-i Balkh. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-968705-3.

- "UNHCR eCentre". Archived from the original on 18 December 2014. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

- https://mevlana-rumi-quotes.blogspot.com/2014/03/maulana-jalal-ud-din-muhammad-rumi.html

- Corbin, Henry (1993) [First published French 1964)]. History of Islamic Philosophy, Translated by Liadain Sherrard, Philip Sherrard. London; Kegan Paul International in association with Islamic Publications for The Institute of Ismaili Studies. pp. 167–175. ISBN 0-7103-0416-1. OCLC 22109949.

- Adamson, Peter (2016). Philosophy in the Islamic World: A History of Philosophy Without Any Gaps. Oxford University Press. p. 113. ISBN 0199577498.

Further reading

- Published in the 19th century

- Edward Balfour (1885), "Balkh", Cyclopaedia of India (3rd ed.), London: B. Quaritch

- Published in the 21st century

- "Balkh". Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art & Architecture. Oxford University Press. 2009.

- Azad, Arezou. Sacred Landscape in Medieval Afghanistan: Revisiting the Faḍāʾil-i Balkh. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-968705-3.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Balkh. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Balkh. |

- The Balkh Art and Cultural Heritage Project housed at the Oriental Institute at the University of Oxford

- Mazar-i-Sharif (Balkh) (in German)

- Explore Balkh with Google Earth on Global Heritage Network

- Indigenous Indian civilization prevailed in Balkh, Afghanistan till the second half of tenth century AD

- "Balkh". Islamic Cultural Heritage Database. Istanbul: Organization of Islamic Cooperation, Research Centre for Islamic History, Art and Culture. Archived from the original on 2013-06-15.

- ArchNet.org. "Balkh". Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA: MIT School of Architecture and Planning. Archived from the original on 2011-09-26.