Eastern Cape Separatist League

The Eastern Province Separatist League was a loose political movement of the 19th century Cape Colony. It fought not for independence, but for a separate British-ruled colony in the eastern half of the Cape Colony, with a more restrictive political system and an expansionist policy eastwards against the remaining independent Xhosa states. It was crushed in the 1870s, and many of its members later moved to the new pro-imperialist, Rhodesian “progressive party”.

Background

For much of the 19th century, the Cape Colony was divided into two main provinces (sometimes known as “circles”) – the Western Province and the Eastern Province. (These entities did not correspond to the modern Western Cape and Eastern Cape provinces of South Africa). The two regions differed in their demographics and their politics.

The two provinces

The larger Western Province had a greater number of Afrikaans-speaking (Coloured and Cape Dutch) voters and was dominated by relatively liberal leaders such as Frank Reitz, William Porter, Saul Solomon, John Molteno and Frank Watermeyer. It tended to favour a more inclusive political system for the colony, and pushed for greater independence from Britain. Its commercial elite also had less material incentive to annex surrounding territory.

The smaller Eastern Province was dominated by British frontier settlers who overall advocated a more “vigorous”, expansionist policy against the neighbouring independent Xhosa states, closer ties with the British Empire, and a more closed, restrictive version of the Cape Qualified Franchise, to prevent the anticipated political mobilisation of the – as yet largely voteless – Xhosa majority of the Eastern Province.[Note 1] It was led by powerful frontier MPs such as William Matthew Harries, Jock Paterson, William Hume and Robert “Moral Bob” Godlonton.

These groupings are generalisations and a great many exceptions existed. Several “eastern” leaders such as Jacobus Sauer, Charles "Xolilizwe" Stretch and Andries Stockenstrom sided with the “liberal” west; while there were MPs such as Philip Stigant and John Thomas Eustace who formed a powerful conservative minority in the west)

A divided parliament

The resentment which inspired Eastern Province separatism originated as early as 1823, in British settlers’ demands for a greater military presence on the frontier. However, the west-east division was not absolute until it was built into the structures of the Cape's legislature.

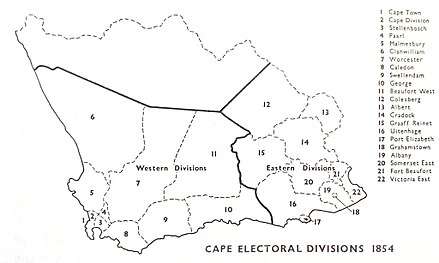

In the second half of the 1800s, the Cape was run by its own parliament (established 1854), based in Cape Town. The west-east regional division was entrenched in the structure of the parliament itself. The lower house (the Legislative Assembly) was elected from a large number of Districts; however the upper house (the Legislative Council) was elected from only the two Provinces (or “Circles”) – the Western and the Eastern and this dichotomy inevitably caused great polarisation. The lower house of parliament in particular was dominated by MPs from the western province, which was larger and had more voters. Eastern province settlers were far fewer in number, and though they were overrepresented in parliament, by an electoral system that favoured urban areas of the Eastern cape, their representatives were still outnumbered in parliament by those of the far larger west. They therefore felt that their concerns, fears and needs were given little sympathy in this western-dominated body.[1]

History

Early growth and disunity (1823-1857)

The Separatist movement in parliament gradually formed as a loose and informal alliance of settler representatives, who advocated for a separate colony for the Eastern Province. The settler representatives felt that a separate colony, with its own parliament, would allow them to pursue their policies of a higher franchise qualification, expansion eastwards, and a greater Imperial military presence.[2]

The movement almost immediately fragmented, and continued to coalesce and re-divide throughout its history, due to the regional interests of different towns, and to a range of ideological differences. The largest and most radical faction was based near the eastern frontier, in the town of Grahamstown, and was therefore variously known as "the frontier party" or "the Grahamstown party". It was characterised by unusually conservative ideology, as well as an association with the Wesleyan church and the Grahams Town Journal newspaper of Robert Godlonton. A more moderate faction was based in Port Elizabeth and its surrounding towns, where the English commercial elite was more concerned with infrastructure and the opening up of markets, than with the simple annexation of territory. Both factions, and the separatist movement overall, was opposed by the second largest political grouping in the Eastern Cape, which drew its support from the Afrikaans speaking Cape Dutch and Coloured voters, as well as more liberal English colonists. Their greatest support lay in the Graaff Reinet area, and the faction came to be known as the "Stockenstromites", after the policies of Andries Stockenstrom.

There were also disagreements in terms of ideology and policy. Firstly, there was disagreement as to which town should be the future capital and seat of parliament for the proposed colony; smaller Eastern towns feared domination by either Port Elizabeth or Grahamstown (often even more than they resented Cape Town’s domination). Secondly, a region of the eastern province formed its own lobby which agitated for a separate “Midlands” colony. Most importantly, subgroups of the Separatist League put forward other solutions to fight the perceived domination of the Western Province. One such group began a political struggle for a system of three parliaments – one for each province and then one overall parliament for the whole Cape Colony. Another group moderated their demands to merely asking that the current parliament be moved away from Cape Town, to a central location midway between east and west. Another smaller group pushed for parliament to rotate, between Port Elizabeth and Cape Town. While most of the movement continued in their separatist aims, these disagreements weakened the league. The separatists also faced opposition from the growing “responsible government” movement, which was based in the west and advocated greater independence for a united Cape.

Apogee (1857-1870)

The league had a rare moment of unity in 1857 when Robert Godlonton led all eastern members of the Legislative Council in resigning in protest. In 1860, opposition to a new tax on wool led to even greater unity when the most powerful business owners in the Eastern Province's wool industry united in opposition to the tax. The Eastern Province MPs, who constituted a large segment of the aforesaid businessmen, formally institutionalised the movement as the "Separatist League" later in 1860. The League supporters remained in a minority however.

It was only in the 1860s, when it gained imperial support, in the person of conservative British Governor Edmund Wodehouse, that it gained an advantage over the liberal majority. Wodehouse sought to divide the Cape and roll back its legislative independence. Working together with Wodehouse's government, the League reached the apogee of its power. It established an office in Port Elizabeth for their central committee, under permanent secretary Dr W. Way, and a less formal office (the “Eastern Province Club House”) in Cape Town. They briefly operated as a relatively united front, to take advantage of the support from the imperial government.

In 1864 they were successful in causing Parliament to be convened in Grahamstown, rather than Cape Town, for the first time. Here, their settler supporters were present in force, and Robert Godlonton's powerful influence on the press helped the League to dominate that year's parliament. Molteno succeeded in rallying the liberals though and eventually prevented the attempts to institutionalise the division.

For roughly a decade, the Cape’s political system was in paralysis. Wodehouse sought to impose the league’s proposals, together with various attempts to curtail the independence of the Cape overall, and the responsible government party used its majority to block the proposals and cut off funding to the Governor’s office. After the eventual triumph of the responsible government party in 1871, the Cape received its first elected executive government and several members of the separatist league defected to the responsible government party.[3]

Decline (1870-1874)

Rising prosperity in the early 1870s led to a decline in the separatist movement’s support. Divisions also arose again, between the main towns of the eastern province. However the principal blow to the movement was the new Cape Prime Minister’s bill of 1874 to break up the two-way division of the Cape, into seven new Provinces (the large, uneven number 7 was specifically chosen to encourage fluidity of regional allegiance, to prevent either deadlock, or entrenched divisions). This “Seven Circles Act” removed the political division which had sustained the separatist movement and made its continued existence unsustainable.[4][5]

Imperial Emissary James Froude made a brief attempt to resurrect the Separatist League in 1878. At the time, the London Colonial Office was implementing a plan to bring all the states of southern Africa into a single, British-controlled Confederation. The united, independence-oriented Cape had opposed this policy, and it was at the time by far the largest and most powerful state in the region. Creating divisions within the Cape, in the interests of eventually bringing it into the planned Confederation, was therefore a prudent strategy. Froude arrived from London and mobilised the remaining separatists who were still politically active. On behalf of the British government, he promised audiences in Port Elizabeth that if they supported the British Confederation Scheme, the eastern province would be reinstated and given its own colony under Britain, within the planned confederation. The promise came to nothing however, as the Confederation attempt collapsed into wars.

One result of the failed confederation attempt was the new political and racial consciousness of the Cape’s Afrikaner population, and the rise of the Afrikaner Bond. Partly because of this, the East-West regional division was replaced with an Anglo-Boer racial division.[6]

Analysis and legacy

While the movement occasionally excited great passions on the ground, the dispute was primarily one between political and economic elites. The opinion of the majority of southern Africans on the matter is difficult to gauge, and the political moves towards separation mostly took place within the stifled and regulated environment of the Cape Parliament.

Little blood was shed directly for the separatist cause, and incidents of violence were rare. The “Uitenhage bunfight” was one such incident. It occurred during the visit to the Cape Colony of the Imperial Emissary James Anthony Froude. Froude championed the separatists cause and successfully conflated their cause with the Imperial attempt to hold a conference around confederating southern Africa. At a rally in the eastern town of Uitenhage on 21 September 1875, John X. Merriman, the representative of the Cape government, complained of “imperial agitation” and accused the separatists of advocating economic systems that constituted slavery in disguise. After he was pelted with buns and other food stuffs by Jock Paterson and his supporters, the event descended into fist-fights between pro and anti-separatist partisans.[7][8][Note 2]

The political descendants of the Separatist League eventually influenced the forming of the pro-imperialist ideologies of John Gordon Sprigg and Cecil Rhodes, and later the “Progressive Party” of Leander Starr Jameson.[9]

See also

References

- JL. McCracken: The Cape Parliament. Clarendon Press: Oxford. 1967

- Kilpin, R.: The Old Cape House, being pages from the history of a legislative assembly. Cape Town: T.M.Miller, 1918.

- WEG Solomon: Saul Solomon, THE member for Cape Town. Oxford University Press. 1948.

- B.A. Le Cordeur: The politics of eastern Cape separatism, 1820-1854. Oxford University Press. 1981.

- Wilmot, A. The History of our own Times in South Africa, Volume 2. J.C. Juta & co., 1899.

- Malherbe, Vertrees Canby: What They Said, 1795-1910: A Selection of Documents from South African History. Maskew Miller. 1971.

- AP Newton: Select Documents Relating to the Unification of South Africa. Routledge 2013. p.30

- AT Wirgman: Storm and Sunshine in South Africa. Longmans, Green and co. 1922. p.58

- C.Saunders, N.Southey. A Dictionary of South African History. New Africa Books: South Africa. 2001. p.63.

Notes

- "The Eastern Province members did not like the idea because they were fewer in number than those of the Western Province, and might thus be outvoted in matters connected with the frontier. Besides, it was such a long way to Cape Town that some of the members were not able to attend Parliament very regularly. They also thought something like this: "If the British Government do not appoint the Executive, they will not be likely to send out soldiers or to pay for our defence if we have another Kaffir war. They will insist that, if they provide the troops and money, all decisions on these matters ought to rest with them."" C.Lewis. Founders and Builders. London : T.C. & E.C. Jack, 1919. pp.162-163.

- "Froude was acclaimed nearly everywhere he went on his speaking tour, but the support he found was not so much for the conference as for his endorsement of pet local causes. Separatists would have separation; the Cape Dutch would have redress for their cousins in the Dutch Republics over Griqualand West; and conservatives would have a strict disciplinary native policy. "Chameleon-like, his politics assumed the colour of his surroundings", said a Cape Argus editorial. Froude became more confident of the success of his mission when his Lord and Master Carnarvon decided to switch the site of the conference to Natal. That decision contained the threat - empty as it turned out because Natal and the Republics would not play ball - that the Confederation might comprise Natal, Griqualand West and one or both Dutch Republics, leaving the Cape out in the cold. These hardball tactics produced exactly the opposite of their intended effect upon the Molteno Ministry. It became more rabid in its anti-Imperialist stance. John X. Merriman, who had come to accept responsible government and had become Molteno's Commissioner of Crown Lands and Public Works, mounted slashing counter-attacks upon Froude, "the Imperial Agent." The rhetoric culminated in the famous bread-roll War. Suffice it to say that, with emotions running very high, it was imprudent for the Mayor of Uitenhage to invite the Imperial Agent to a luncheon in honour of the Minister of Crown Lands and Public Works. As Merriman got warmed up on the subject of Imperial agitation, guests - including Paterson - interrupted the Minister, to the annoyance of his supporters. The culmination was a bombardment of the top table with bread rolls, and fist fights among guests. Merriman's remarks may have been ill-advised and intemperate, but the incident did at least persuade Froude to stop making speeches." Basil T. Hone: The First Son of South Africa to be Premier: Thomas Charles Scanlen. Oldwick, New Jersey: Longford Press, 1993. p.61.