Northern Cape

The Northern Cape (Afrikaans: Noord-Kaap; Tswana: Kapa Bokone; Xhosa: uMntla-Koloni) is the largest and most sparsely populated province of South Africa. It was created in 1994 when the Cape Province was split up. Its capital is Kimberley. It includes the Kalahari Gemsbok National Park, part of the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park and an international park shared with Botswana. It also includes the Augrabies Falls and the diamond mining regions in Kimberley and Alexander Bay.

Northern Cape Noord-Kaap (in Afrikaans) Kapa Bokone (in Tswana) uMntla-Kapa (in Xhosa) | |

|---|---|

Coat of arms | |

| Motto(s): Sa ǁa ǃaĩsi 'uĩsi (Strive for a better life) | |

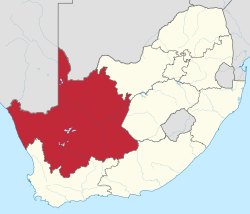

Location of the Northern Cape in South Africa | |

| Country | South Africa |

| Established | 27 April 1994 |

| Capital | Kimberley |

| Districts | |

| Government | |

| • Type | Parliamentary system |

| • Premier | Zamani Saul (ANC) |

| • Legislature | Northern Cape Provincial Legislature |

| Area [1]:9 | |

| • Total | 372,889 km2 (143,973 sq mi) |

| Area rank | 1st in South Africa |

| Highest elevation | 2,156 m (7,073 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 1,145,861 |

| • Estimate (2020) | 1,292,786 |

| • Rank | 9th in South Africa |

| • Density | 3.1/km2 (8.0/sq mi) |

| • Density rank | 9th in South Africa |

| Population groups [1]:21 | |

| • Black | 50.4% |

| • Coloured | 40.3% |

| • White | 7.1% |

| • Indian or Asian | 1.7% |

| Languages [1]:25 | |

| • Afrikaans | 53.8% |

| • Tswana | 33.1% |

| • Xhosa | 5.3% |

| • English | 3.4% |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (SAST) |

| ISO 3166 code | ZA-NC |

| HDI (2018) | 0.694[3] medium · 6th |

| Website | www.northern-cape.gov.za |

The Namaqualand region in the west is famous for its Namaqualand daisies. The southern towns of De Aar and Colesberg found within the Great Karoo are major transport nodes between Johannesburg, Cape Town and Port Elizabeth. Kuruman can be found in the north-east and is known as a mission station. It is also well known for its artesian spring and Eye of Kuruman. The Orange River flows through the province of Northern Cape, forming the borders with the Free State in the southeast and with Namibia to the northwest. The river is also used to irrigate the many vineyards in the arid region near Upington.

Native speakers of Afrikaans comprise a higher percentage of the population in the Northern Cape than in any other province. The Northern Cape's four official languages are Afrikaans, Tswana, Xhosa, and English. Minorities speak the other official languages of South Africa and a few people speak indigenous languages such as Nama and Khwe.

The provincial motto, Sa ǁa ǃaĩsi 'uĩsi ("We go to a better life"), is in the Nǀu language of the Nǁnǂe (ǂKhomani) people. It was given in 1997 by one of the language's last speakers, Ms. Elsie Vaalbooi of Rietfontein, who has since died. It was South Africa's first officially registered motto in a Khoisan language. Subsequently, South Africa's national motto, ǃKe e ǀxarra ǁke, was derived from the extinct Northern Cape ǀXam language.

History

The Northern Cape was one of three provinces made out of the Cape Province in 1994, the others being Western Cape to the south and Eastern Cape to the southeast. Politically, it had been dominated since 1994 by the African National Congress (ANC).[4] Ethnic issues are important in the politics of the Northern Cape. For example, it is the site of the Orania settlement, whose leaders have called for a Volkstaat for the Afrikaner people in the province.

The Northern Cape is also the home of over 1,000 San who immigrated from Namibia following the independence of the country; they had served as trackers and scouts for the South African Defence Force during the South African Border War, and feared reprisals from their former foes. They were awarded a settlement in Platfontein in 1999 by the Mandela government.

The precolonial history of the Northern Cape is reflected in a rich, mainly Stone Age, archaeological heritage. Cave sites include Wonderwerk Cave near Kuruman, which has a uniquely long sequence stretching from the turn of the twentieth century at the surface to more than 1 million (and possibly nearly 2 million) years in its basal layer (where stone tools, occurring in very low density, may be Oldowan).[5][6] Many sites across the province, mostly in open air locales or in sediments alongside rivers or pans, document Earlier, Middle and Later Stone Age habitation. From Later Stone Age times, mainly, there is a wealth of rock art sites – most of which are in the form of rock engravings such as at Wildebeest Kuil and many sites in the area known as ǀXam -ka !kau, in the Karoo. They occur on hilltops, slopes, rock outcrops and occasionally (as in the case of Driekops Eiland near Kimberley), in a river bed.[7] In the north eastern part of the province there are sites attributable to the Iron Age such as Dithakong.[8] Environmental factors have meant that the spread of Iron Age farming westwards (from the 17th century – but dating from the early first millennium AD in the eastern part of South Africa) was constrained mainly to the area east of the Langeberg Mountains, but with evidence of influence as far as the Upington area in the eighteenth century. From that period the archaeological record also reflects the development of a complex colonial frontier when precolonial social formations were considerably disrupted and there is an increasing 'fabric heavy' imprint of built structures, ash-heaps, and so on. The copper mines of Namaqualand and the diamond rush to the Kimberley area resulted in industrial archaeological landscapes in those areas which herald the modern era in South African history.

Government

The provincial government consists of a premier, an executive council of ten ministers, and a legislature. The provincial assembly and premier are elected for five-year terms, or until the next national election. Political parties are awarded assembly seats based on the percentage of votes each party receives in the province during the national elections. The assembly elects a premier, who then appoints the members of the executive council. The premier of the Northern Cape as of 2019 is Zamani Saul of the African National Congress.

Political history

The politics of the Northern Cape are dominated by the African National Congress (ANC), but their position has not been as strong as in the other provinces. Initially, no party had an absolute majority. In 1994 the ANC's Manne Dipico became the first Premier of the Northern Cape after Ethne Papenfus, the sole elected representative of the Democratic Party (DP), voted with the ANC. In return, she was elected speaker of the legislature.[9]

The ANC increased its voter share in later elections and has remained firmly in charge of the province after 1999. Dipuo Peters replaced Dipico as Premier in 2004. The official opposition in the Northern Cape after the 2004 elections was the Democratic Alliance, receiving 11% of the vote in the provincial ballot. The opposition's hopes of unseating the ANC has not had any success, even with the Congress of the People (COPE), a splinter party from the ANC, helping to split the vote in the election of 22 April 2009. Hazel Jenkins became Premier following the election, and COPE became the official opposition. Jenkins was later replaced by Sylvia Lucas in 2013.

The 2014 election saw the ANC returned to power once again with an increased mandate, while DA once again became the official opposition, after the collapse of COPE. The newly-formed Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) also entered the legislature for the first time. Sylvia Lucas was re-elected to her first full term.[10]

In the 2019 election, the Northern Cape was considered competitive. The opposition DA planned on taking over the province. The ANC returned as the majority party but the party's support had dropped. The DA was once again the official opposition with an increased seat total. The EFF made gains, while the Freedom Front Plus (FF+) won a seat in the legislature for the first time since 2004.[11]

Geography

The Northern Cape is South Africa's largest province, and distances between towns are enormous due to its sparse population. Its size is just shy of the size of the American state of Montana and slightly larger than that of Germany. The province is dominated by the Karoo Basin and consists mostly of sedimentary rocks and some dolerite intrusions. The south and south-east of the province is high-lying, 1,200–1,900 metres (3,900–6,200 ft), in the Roggeveld and Nuweveld districts. The west coast is dominated by the Namaqualand region, famous for its spring flowers. This area is hilly to mountainous and consists of Granites and other metamorphic rocks. The central areas are generally flat with interspersed salt pans. Kimberlite intrusions punctuate the Karoo rocks, giving the province its most precious natural resource, diamonds. The north is primarily Kalahari Desert, characterised by parallel red sand dunes and acacia tree dry savanna.

Northern Cape has a shoreline in the west on the South Atlantic Ocean. It borders the following areas of Namibia and Botswana:

- ǁKaras Region, Namibia – northwest

- Hardap Region, Namibia – far northwest

- Kgalagadi District, Botswana – north

Domestically, it borders the following provinces:

- North West – northeast

- Free State – east

- Eastern Cape – southeast

- Western Cape – south and southwest

Rivers

The major river system is the Orange (or Gariep) River Basin, draining the interior of South Africa westwards into the Atlantic Ocean. (The political philosopher Neville Alexander has used the idea of the ‘Garieb’ as a metaphor for nationhood in South Africa, a flowing together, in preference to the rainbow metaphor where the diverse colours remain distinct).[12] The principal tributary of the Orange is the Vaal River, which flows through part of the Northern Cape from the vicinity of Warrenton. The Vaal, in turn, has tributaries within the province: the Harts River and the Riet River, which has its own major tributary, the Modder River.

Above the Orange-Vaal confluence, the Seekoei River drains part of the northeastern Karoo into the Orange River above the Vanderkloof Dam. Next downstream from the Orange-Vaal confluence is the Brak River, which flows nonperennially from the south and is in turn fed by the Ongers River, rising in the vicinities of Hanover and Richmond respectively. Along the Orange River near the town of Kakamas, the Hartebeest River drains the central Karoo. Above Kenhardt the Hartebeest is known as the Sak River, which has its source on the northern side of the escarpment, southeast of Williston. Further downstream from Kakamas, below the Augrabies Falls, and seldom actually flowing into the Orange River, is the Molopo River, which comes down from the Kalahari in the north. With its tributary, the Nossob River, it defines part of the international boundary between South Africa and Botswana. Further tributaries of the Molopo River include the Kuruman River, fed by the Moshaweng River and Kgokgole River, and the Matlhwaring River. Flowing west into the Atlantic, in Namaqualand, is the Buffels River and, further south, the Groen River.

Climate

Mostly arid to semiarid, few areas in the province receive more than 400 mm (16 in) of rainfall per annum and the average annual rainfall over the province is 202 mm (8.0 in).[13] Rainfall generally increases from west to east from a minimum average of 20 mm (0.79 in) to a maximum of 540 mm (21 in) per year. The west experiences most rainfall in winter, while the east receives most of its moisture from late summer thunderstorms. Many areas experience extreme heat, with the hottest temperatures in South Africa measured along the Namibian border. Summers maximums are generally 30 °C (86 °F) or higher, sometimes higher than 40 °C (104 °F). Winters are usually frosty and clear, with southern areas sometimes becoming bitterly cold, such as Sutherland, which often receives snow and temperatures occasionally drop below the −10 °C (14 °F) mark.

- Kimberley averages: January maximum: 33 °C (91 °F) (min: 18 °C (64 °F)), June maximum: 18 °C (64 °F) (min: 3 °C (37 °F)), annual precipitation: 414 mm (16.3 in)

- Springbok averages: January maximum: 30 °C (86 °F) (min: 15 °C (59 °F)), July maximum: 17 °C (63 °F) (min: 7 °C (45 °F)), annual precipitation: 195 mm (7.7 in)

- Sutherland averages: January maximum: 27 °C (81 °F) (min: 9 °C (48 °F)), July maximum: 13 °C (55 °F) (min: −3 °C (27 °F)), annual precipitation: 237 mm (9.3 in)

Municipalities

.svg.png)

The Northern Cape Province is divided into five district municipalities. The district municipalities are in turn divided into 27 local municipalities:

District municipalities

Cities and towns

Population 50,000+

- Kimberley

- Upington

Population 10,000+

- Douglas

- Barkly West

- Colesberg

- De Aar

- Jan Kempdorp

- Kathu

- Kuruman

- Postmasburg

- Prieska

- Springbok

- Victoria West

- Warrenton

Population < 10,000

Economy of the Northern Cape

As reported by the Northern Cape Provincial Government, unemployment still remains a big issue in the province. Unemployment was reported to be at 24.9% during Q4, 2013. Unemployment also declined from 119,000 in Q4, 2012 to 109,000 in Q4, 2013.[14]

The Northern Cape is also home to the Square Kilometer Array (SKA), which is located 75 km North-West of Carnarvon.

The economy of the Northern Cape relies heavily on two sectors, mining and agriculture, which employ 57% (Tertiary Sector) of all employees in the province.

Most famous for the diamond mines around Kimberley, the Northern Cape also has a substantial agricultural area around the Orange River, including most of South Africa's sultana vineyards. Some Wine of Origin areas have been demarcated. The Orange River also attracts visitors who enjoy rafting tours around Vioolsdrif. Extensive sheep raising is the basis of the economy in the southern Karoo areas of the province.

Demographics

|

<1 /km2

1–3 /km2

3–10 /km2

10–30 /km2

30–100 /km2 |

100–300 /km2

300–1000 /km2

1000–3000 /km2

>3000 /km2 |

About 68% of the population are first-language Afrikaans speakers, other primary languages being Setswana, Xhosa and English. To the extent that apartheid-era population classification persists, the majority of the Northern Cape population is characterised as Coloured.[15]

People who self-identify as San people, some of whom retain distinct indigenous cultural elements such as Khoisan languages, but no longer subsist by hunting and gathering, live in the Northern Cape.

See also

- Northern Cape Provincial Legislature

- Griqualand West

- List of Speakers of the Northern Cape Provincial Legislature

References

- Census 2011: Census in brief (PDF). Pretoria: Statistics South Africa. 2012. ISBN 9780621413885. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 May 2015.

- Mid-year population estimates, 2020 (PDF) (Report). Statistics South Africa. 9 July 2020. p. 2. Retrieved 9 July 2020.

- "Sub-national HDI - Area Database - Global Data Lab". hdi.globaldatalab.org. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- sahoboss (31 March 2011). "Northern Cape". www.sahistory.org.za. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- Beaumont, P.B.; Vogel, J.C. (2006). "On a timescale for the past million years of human history in central South Africa". South African Journal of Science (102): 217–228. hdl:10204/1944.

- Chazan, Michael; Ron, Hagai; Matmon, Ari; Porat, Naomi; Goldberg, Paul; Yates, Royden; Avery, Margaret; Sumner, Alexandra; Horwitz, Liora Kolska (2008). "Radiometric dating of the Earlier Stone Age sequence in Excavation I at Wonderwerk Cave, South Africa: preliminary results". Journal of Human Evolution. 55 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2008.01.004. ISSN 0047-2484.

- Parkington, J. Morris, D. & Rusch, N. 2008. Karoo rock engravings. Clanwilliam: Krakadouw Trust

- Morris, D. & Beaumont, P. 2004. Archaeology in the Northern Cape: some key sites. Kimberley: McGregor Museum.

- Sunday Times. 8 May 1994. The country's legislators vow they will serve new SA

- De Wet, Phillip (8 May 2014). "Elections: DA, EFF demolish Cope in Northern Cape". Mail & Guardian. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- Mahlati, Zintle (10 May 2019). "ANC retains North West, Northern Cape with reduced majorities". IOL. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- Alexander, Neville. 2002. An ordinary country, pp 106–107

- Dent, M.C., Lynch, S.D. & Schulze, R.E. 1989. Mapping Mean Annual and Other Rainfall Statistics over Southern Africa. Water Research Commission, Petoria. WRC Report 109/1/89.

- http://economic.ncape.gov.za/index.php?option=com_phocadownload&view=category&id=3&Itemid=365

- "A Profile of the Northern Cape Province: Demographics, Poverty, Income, Inequality and Unemployment from 2000 till 2007 (archived copy)" (PDF). PROVIDE project. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 June 2011. Retrieved 2 August 2011.