Holi

Holi ( /ˈhoʊliː/) is a popular ancient Hindu festival, also known as the Indian "festival of spring", the "festival of colours", or the "festival of love".[8][1][9] The festival signifies the victory of good over evil.[10][11] It originated and is predominantly celebrated in India, but has also spread to other regions of Asia and parts of the Western world through the diaspora from the Indian subcontinent.

| Holi | |

|---|---|

| |

| Observed by | Hindus,[1] Sikhs, Jains,[2] Newar Buddhists[3] and other secular non-Hindus[4] |

| Type | Religious, cultural, spring festival |

| Celebrations | Night before: Holika Bonfire On Holi: spray colours on others, dance, party, eating festival delicacies[5] |

| Date | per Hindu calendar[note 1] |

| 2020 date | Monday, 10 March[6] |

| 2021 date | Monday, 29 March[7] |

| Frequency | Annual |

Holi celebrates the arrival of spring, the end of winter, the blossoming of love, and for many it's a festive day to meet others, play and laugh, forget and forgive, and repair broken relationships.[12][13] The festival also celebrates the beginning of a good spring harvest season.[12][13] It lasts for a night and a day, starting on the evening of the Purnima (Full Moon day) falling in the Hindu calendar month of Phalguna, which falls around middle of March in the Gregorian calendar. The first evening is known as Holika Dahan (burning of demon holika) or Chhoti Holi and the following day as Holi, Rangwali Holi, Dhuleti, Dhulandi,[14] or Phagwah.[15]

Holi is an ancient Hindu religious festival which has become popular among non-Hindus as well in many parts of South Asia, as well as people of other communities outside Asia.[12] In addition to India and Nepal, the festival is celebrated by Indian subcontinent diaspora in countries such as Jamaica,[16] Suriname, Guyana, Trinidad and Tobago, South Africa, Malaysia, the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, Mauritius, and Fiji.[8][17] In recent years the festival has spread to parts of Europe and North America as a spring celebration of love, frolic, and colours.[18][17][19]

Holi celebrations start on the night before Holi with a Holika Dahan where people gather, perform religious rituals in front of the bonfire, and pray that their internal evil be destroyed the way Holika, the sister of the demon king Hiranyakashipu, was killed in the fire. The next morning is celebrated as Rangwali Holi – a free-for-all festival of colours,[12] where people smear each other with colours and drench each other. Water guns and water-filled balloons are also used to play and colour each other. Anyone and everyone is fair game, friend or stranger, rich or poor, man or woman, children, and elders. The frolic and fight with colours occurs in the open streets, parks, outside temples and buildings. Groups carry drums and other musical instruments, go from place to place, sing and dance. People visit family, friends and foes come together to throw coloured powders on each other, laugh and gossip, then share Holi delicacies, food and drinks.[20][21] Some customary drinks include bhang (made from cannabis), which is intoxicating.[22][23] In the evening, after sobering up, people dress up and visit friends and family.[5][20]

Cultural significance

The Holi festival has a cultural significance among various Hindu traditions of the Indian subcontinent. It is the festive day to end and rid oneself of past errors, to end conflicts by meeting others, a day to forget and forgive. People pay or forgive debts, as well as deal anew with those in their lives. Holi also marks the start of spring, for many the start of the new year, an occasion for people to enjoy the changing seasons and make new friends.[13][24]

Krishna legend

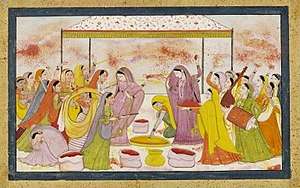

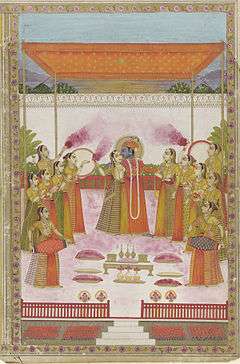

In the Braj region of India, where the Hindu deity Krishna grew up, the festival is celebrated until Rang Panchmi in commemoration of the divine love of Radha for Krishna. The festivities officially usher in spring, with Holi celebrated as a festival of love.[25] There is a symbolic myth behind commemorating Krishna as well. As a baby, Krishna developed his characteristic dark skin colour because the she-demon Putana poisoned him with her breast milk.[26] In his youth, Krishna despaired whether the fair-skinned Radha would like him because of his dark skin colour. His mother, tired of his desperation, asks him to approach Radha and ask her to colour his face in any colour she wanted. This she did, and Radha and Krishna became a couple. Ever since, the playful colouring of Radha and Krishna's face has been commemorated as Holi.[27][28] Beyond India, these legends help to explain the significance of Holi (Phagwah) are common in some Caribbean and South American communities of Indian origin such as Guyana and Trinidad and Tobago.[29][30] It is also celebrated with great fervour in Mauritius.[31]

Vishnu legend

There is a symbolic legend to explain why Holi is celebrated as a festival of triumph of good over evil in the honour of Hindu god Vishnu and his devotee Prahlada. King Hiranyakashipu, according to a legend found in chapter 7 of Bhagavata Purana,[32][33] was the king of demonic Asuras, and had earned a boon that gave him five special powers: he could be killed by neither a human being nor an animal, neither indoors nor outdoors, neither at day nor at night, neither by astra (projectile weapons) nor by any shastra (handheld weapons), and neither on land nor in water or air. Hiranyakashipu grew arrogant, thought he was God, and demanded that everyone worship only him.[5] Hiranyakashipu's own son, Prahlada, however, disagreed. He was and remained devoted to Vishnu.[20] This infuriated Hiranyakashipu. He subjected Prahlada to cruel punishments, none of which affected the boy or his resolve to do what he thought was right. Finally, Holika, Prahlada's evil aunt, tricked him into sitting on a pyre with her.[5] Holika was wearing a cloak that made her immune to injury from fire, while Prahlada was not. As the fire roared, the cloak flew from Holika and encased Prahlada,[20] who survived while Holika burned. Vishnu, the god who appears as an avatar to restore Dharma in Hindu beliefs, took the form of Narasimha – half human and half lion (which is neither a human nor an animal), at dusk (when it was neither day nor night), took Hiranyakashyapu at a doorstep (which was neither indoors nor outdoors), placed him on his lap (which was neither land, water nor air), and then eviscerated and killed the king with his lion claws (which were neither a handheld weapon nor a launched weapon).[34]

The Holika bonfire and Holi signifies the celebration of the symbolic victory of good over evil, of Prahlada over Hiranyakashipu, and of the fire that burned Holika.[13]

Kama and Rati legend

Among other Hindu traditions such as Shaivism and Shaktism, the legendary significance of Holi is linked to Shiva in yoga and deep meditation, goddess Parvati wanting to bring back Shiva into the world, seeks help from the Hindu god of love called Kamadeva on Vasant Panchami. The love god shoots arrows at Shiva, the yogi opens his third eye and burns Kama to ashes. This upsets both Kama's wife Rati (Kamadevi) and his own wife Parvati. Rati performs her own meditative asceticism for forty days, upon which Shiva understands, forgives out of compassion and restores the god of love. This return of the god of love, is celebrated on the 40th day after Vasant Panchami festival as Holi.[35][36] The Kama legend and its significance to Holi has many variant forms, particularly in South India.[37]

Other Indian religions

The festival has traditionally been also observed by non-Hindus, such as by Jains[2] and Newar Buddhists (Nepal).[3]

In Mughal India, Holi was celebrated with such exuberance that people of all castes could throw colour on the Emperor.[38] According to Sharma (2017), "there are several paintings of Mughal emperors celebrating Holi".[39] Grand celebrations of Holi were held at the Lal Qila, where the festival was also known as Eid-e-gulaabi or Aab-e-Pashi.[38] Mehfils were held throughout the walled city of Delhi with aristocrats and traders alike participating.[38] This however changed during the rule of Emperor Aurangzeb. He banned the public celebration of Holi using a Farman issue in November 1665.[40] Bahadur Shah Zafar himself wrote a song for the festival, while poets such as Amir Khusrau, Ibrahim Raskhan, Nazeer Akbarabadi and Mehjoor Lakhnavi relished it in their writings.[38]

Sikhs have traditionally celebrated the festival, at least through the 19th century,[41] with its historic texts referring to it as Hola.[42] Guru Gobind Singh – the last human guru of the Sikhs – modified Holi with a three-day Hola Mohalla extension festival of martial arts. The extension started the day after the Holi festival in Anandpur Sahib, where Sikh soldiers would train in mock battles, compete in horsemanship, athletics, archery and military exercises.[43][44][45]

Holi was observed by Maharaja Ranjit Singh and his Sikh Empire that extended across what are now northern parts of India and Pakistan. According to a report by Tribune India, Sikh court records state that 300 mounds of colours were used in 1837 by Ranjit Singh and his officials in Lahore. Ranjit Singh would celebrate Holi with others in the Bilawal gardens, where decorative tents were set up. In 1837, Sir Henry Fane who was the commander-in-chief of the British Indian army joined the Holi celebrations organised by Ranjit Singh. A mural in the Lahore Fort was sponsored by Ranjit Singh and it showed the Hindu god Krishna playing Holi with gopis. After the death of Ranjit Singh, his Sikh sons and others continued to play Holi every year with colours and lavish festivities. The colonial British officials joined these celebrations.[46]

Description

Holi is an important spring festival for Hindus, a national holiday in India and Nepal with regional holidays in other countries. To many Hindus and some non-Hindus, it is a playful cultural event and an excuse to throw coloured water at friends or strangers in jest. It is also observed broadly in the Indian subcontinent. Holi is celebrated at the end of winter, on the last full moon day of the Hindu luni-solar calendar month marking the spring, making the date vary with the lunar cycle.[note 1] The date falls typically in March, but sometimes late February of the Gregorian calendar.[49][50]

The festival has many purposes; most prominently, it celebrates the beginning of Spring. In 17th century literature, it was identified as a festival that celebrated agriculture, commemorated good spring harvests and the fertile land.[12] Hindus believe it is a time of enjoying spring's abundant colours and saying farewell to winter. To many Hindus, Holi festivities mark the beginning of the new year as well as an occasion to reset and renew ruptured relationships, end conflicts and rid themselves of accumulated emotional impurities from the past.[13][24]

It also has a religious purpose, symbolically signified by the legend of Holika. The night before Holi, bonfires are lit in a ceremony known as Holika Dahan (burning of Holika) or Little Holi. People gather near fires, sing and dance. The next day, Holi, also known as Dhuli in Sanskrit, or Dhulheti, Dhulandi or Dhulendi, is celebrated.

In Northern parts of India, Children and youth spray coloured powder solutions (gulal) at each other, laugh and celebrate, while adults smear dry coloured powder (abir) on each other's faces.[5][24] Visitors to homes are first teased with colours, then served with Holi delicacies (such as puranpoli, dahi-bada and gujia), desserts and drinks.[21][51][52] After playing with colours, and cleaning up, people bathe, put on clean clothes, and visit friends and family.[13]

Like Holika Dahan, Kama Dahanam is celebrated in some parts of India. The festival of colours in these parts is called Rangapanchami, and occurs on the fifth day after Poornima (full moon).[53]

History and rituals

The Holi festival is an ancient Hindu festival with its cultural rituals. It is mentioned in the Puranas, Dasakumara Charita, and by the poet Kālidāsa during the 4th century reign of Chandragupta II.[8] The celebration of Holi is also mentioned in the 7th-century Sanskrit drama Ratnavali.[54] The festival of Holi caught the fascination of European traders and British colonial staff by the 17th century. Various old editions of Oxford English Dictionary mention it, but with varying, phonetically derived spellings: Houly (1687), Hooly (1698), Huli (1789), Hohlee (1809), Hoolee (1825), and Holi in editions published after 1910.[12]

There are several cultural rituals associated with Holi:[55]

Holika Dahan

Preparation

Days before the festival people start gathering wood and combustible materials for the bonfire in parks, community centers, near temples and other open spaces. On top of the pyre is an effigy to signify Holika who tricked Prahalad into the fire. Inside homes, people stock up on pigments, food, party drinks and festive seasonal foods such as gujiya, mathri, malpuas and other regional delicacies.

Bonfire

On the eve of Holi, typically at or after sunset, the pyre is lit, signifying Holika Dahan. The ritual symbolises the victory of good over evil. People gather around the fire to sing and dance.[13]

Play

Playing with colours

In North and Western India, Holi frolic and celebrations begin the morning after the Holika bonfire. Children and young people form groups armed with dry colours, coloured solution and water guns (pichkaris), water balloons filled with coloured water, and other creative means to colour their targets.[55]

Traditionally, washable natural plant-derived colours such as turmeric, neem, dhak, and kumkum were used, but water-based commercial pigments are increasingly used. All colours are used. Everyone in open areas such as streets and parks is game, but inside homes or at doorways only dry powder is used to smear each other's face. People throw colours and get their targets completely coloured up. It is like a water fight, but with coloured water. People take delight in spraying coloured water on each other. By late morning, everyone looks like a canvas of colours. This is why Holi is given the name "Festival of Colours".

Groups sing and dance, some playing drums and dholak. After each stop of fun and play with colours, people offer gujiya, mathri, malpuas and other traditional delicacies.[56] Cold drinks, including drinks made with marijuana,[23] are also part of the Holi festivity.

Other variations

In the Braj region around Mathura, in north India, the festivities may last more than a week. The rituals go beyond playing with colours, and include a day where men go around with shields and women have the right to playfully beat them on their shields with sticks.[57]

In south India, some worship and make offerings to Kamadeva, the love god of Indian mythology.

Later in the day

After a day of play with colours, people clean up, wash and bathe, sober up and dress up in the evening and greet friends and relatives by visiting them and exchanging sweets. Holi is also a festival of forgiveness and new starts, which ritually aims to generate harmony in society.[55]

Regional names, rituals and celebrations

Holi (Hindi: होली, Marathi: होळी, Nepali: होली, Punjabi: ਹੋਲੀ, Kannada: ಹೋಳಿ, Telugu: హోళి) is also known as Phakuwa or Phagwah (Assamese: ফাকুৱা), Festival of Colours, or Dola jātra (Odia: ଦୋଳଯାତ୍ରା) in Odisha, and as Dol Jatra (Assamese: দ’ল যাত্ৰা) or Basanto utsav (Bengali: বসন্ত উত্সব) ("Spring festival") in West Bengal, Tripura and Assam. The customs and celebrations vary between regions of India.

Holi is of particular significance in the Braj region, which includes locations traditionally associated with the Lord Krishna: Mathura, Vrindavan, Nandgaon, Uttar Pradesh, and Barsana, which become touristic during the season of Holi.[25]

Outside India and Nepal, Holi is observed by the minority Hindus in Bangladesh and Pakistan as well in countries with large Indian subcontinent diaspora populations such as Suriname, Guyana, Trinidad and Tobago, South Africa, Malaysia, the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, Australia, Mauritius, and Fiji. The Holi rituals and customs outside South Asia also vary with local adaptations.

India

Assam

Holi, also called Phakuwa/Doul (ফাকুৱা/দৌল) in Assamese, is celebrated all over Assam. Locally called Doul Jatra, associated with Satras of Barpeta, Holi is celebrated over two days. On the first day, the burning of clay huts are seen in Barpeta and lower Assam which signifies the legends of Holika. On the second day of it, Holi is celebrated with colour powders. The Holi songs in chorus devoted to Lord Krishna are also sung in the regions of Barpeta.

Bihar/Jharkhand

Holi is known as Phaguwa in the local Bhojpuri dialect. In this region as well, the legend of Holika is prevalent. On the eve of Phalgun Poornima, people light bonfires. They put dried cow dung cakes, wood of the Araad or Redi tree and Holika tree, grains from the fresh harvest and unwanted wood leaves in the bonfire. At the time of Holika people assemble near the pyre. The eldest member of the gathering or a purohit initiates the lighting. He then smears others with colour as a mark of greeting. Next day the festival is celebrated with colours and a lot of frolic. Traditionally, people also clean their houses to mark the festival.

Holi Milan is also observed in Bihar, where family members and well-wishers visit each other's family, apply colours (abeer) on each other's faces, and on feet, if elderly. Usually this takes place on the evening of Holi day after Holi with wet colours is played in the morning through the afternoon. Due to large-scale internal migration issues faced by the people, recently this tradition has slowly begun to transform, and it is common to have Holi Milan on an entirely different day either before or after the actual day of Holi.[58]

Children and youths take extreme delight in the festival. Though the festival is usually celebrated with colours, in some places people also enjoy celebrating Holi with water solutions of mud or clay. Folk songs are sung at high pitch and people dance to the sound of the dholak (a two-headed hand-drum) and the spirit of Holi. Intoxicating bhang, made from cannabis, milk and spices, is consumed with a variety of mouth-watering delicacies, such as pakoras and thandai, to enhance the mood of the festival.[59]

Goa

Holi is locally called Ukkuli in Konkani. It is celebrated around the Konkani temple called Gosripuram temple. It is a part of the Goan or Konkani spring festival known as Śigmo or शिगमो in Koṅkaṇī or Śiśirotsava, which lasts for about a month. The colour festival or Holi is a part of longer, more extensive spring festival celebrations.[60] Holi festivities (but not Śigmo festivities) include: Holika Puja and Dahan, Dhulvad or Dhuli vandan, Haldune or offering yellow and saffron colour or Gulal to the deity.

Gujarat

In Gujarat, Holi is a two-day festival. On the evening of the first day people light the bonfire. People offer raw coconut and corn to the fire. The second day is the festival of colour or "Dhuleti", celebrated by sprinkling coloured water and applying colours to each other. Dwarka, a coastal city of Gujarat, celebrates Holi at the Dwarkadheesh temple and with citywide comedy and music festivities.[61] Falling in the Hindu month of Phalguna, Holi marks the agricultural season of the rabi crop.

In Ahmedabad in Gujarat, in western India, a pot of buttermilk is hung high over the streets and young boys try to reach it and break it by making human pyramids. The girls try to stop them by throwing coloured water on them to commemorate the pranks of Krishna and the cowherd boys to steal butter and "gopis" while trying to stop the girls. The boy who finally manages to break the pot is crowned the Holi King. Afterwards, the men, who are now very colourful, go out in a large procession to "alert" people of Krishna's possible appearance to steal butter from their homes.

In some places, there is a custom in undivided Hindu families that the woman beats her brother-in-law with a sari rolled up into a rope in a mock rage and tries to drench him with colours, and in turn, the brother-in-law brings sweets (Indian desserts) to her in the evening.[62]

Jammu and Kashmir

In Jammu and Kashmir, Holi celebrations are much in line with the general definition of Holi celebrations: a high-spirited festival to mark the beginning of the harvesting of the summer crop, with the throwing of coloured water and powder and singing and dancing.[63]

Karnataka

Traditionally, in rural Karnataka children collect money and wood in the weeks prior to Holi, and on "Kamadahana" night all the wood is put together and lit. The festival is celebrated for two days. People in northern parts of Karnataka prepare special food on this day.

In Sirsi, Karnataka, Holi is celebrated with a unique folk dance called "Bedara Vesha", which is performed during the nights beginning five days before the actual festival day. The festival is celebrated every alternate year in the town, which attracts a large number of tourists from different parts of India.[64]

Maharashtra

In Maharashtra, Holi Purnima is also celebrated as Shimga, festivities that last five to seven days. A week before the festival, youngsters go around the community, collecting firewood and money. On the day of Shimga, the firewood is heaped into a huge pile in each neighborhood. In the evening, the fire is lit. Every household brings a meal and dessert, in the honour of the fire god. Puran Poli is the main delicacy and children shout "Holi re Holi puranachi poli". Shimga celebrates the elimination of all evil. The colour celebrations here take place on the day of Rang Panchami, five days after Shimga. During this festival, people are supposed to forget and forgive any rivalries and start new healthy relations with all.

Manipur

Manipuris celebrate Holi for 6 days. Here, this holiday merges with the festival of Yaosang. Traditionally, the festival commences with the burning of a thatched hut of hay and twigs. Young children go from house to house to collect money, locally known as nakadeng (or nakatheng), as gifts on the first two days. The youths at night perform a group folk dance called Thabal chongba on the full moon night of Lamta (Phalgun), traditionally accompanied by folk songs and rhythmic beats of the indigenous drum, but nowadays by modern bands and fluorescent lamps. In Krishna temples, devotees sing devotional songs, perform dances and celebrate with aber (gulal) wearing traditional white and yellow turbans. On the last day of the festival, large processions are taken out to the main Krishna temple near Imphal where several cultural activities are held. In recent decades, Yaosang, a type of Indian sport, has become common in many places of the valley, where people of all ages come out to participate in a number of sports that are somewhat altered for the holiday.

Odisha

The people of Odisha celebrate "Dola" on the day of Holi where the icons of Jagannath replace the icons of Krishna and Radha. Dola Melana, processions of the deities are celebrated in villages and bhoga is offered to the deities. "Dola yatra" was prevalent even before 1560 much before Holi was started where the idols of Jagannath, Balabhadra and Subhadra used to be taken to the "Dolamandapa" (podium in Jagannath temple).[66] People used to offer natural colours known as "abira" to the deities and apply on each other's feats.[67]

Punjab

In Punjab, the eight days preceding Holi are known as luhatak.[68] Sekhon (2000) states that people start throwing colours many days before Holi.[69]

Holi is preceded by Holika Dahan the night before when a fire is lit. Historically, the Lubana community of Punjab celebrated holi "with great pomp and show. The Lubanas buried a pice and betel nut. They heaped up cow-dung cakes over the spot and made a large fire. When the fire had burnt out, they proceeded to hunt for the pice and betel-nut. Whosoever found these, was considered very lucky."[70] Elsewhere in Punjab, Holi was also associated with making fools of others. Bose writing in Cultural Anthropology: And Other Essays in 1929 noted that "the custom of playing Holi-fools is prevalent in Punjab".[71]

On the day of Holi, people engage in throwing colours[72] on each other.[73] For locals, Holi marks the end of winter. The Punjabi saying Phaggan phal laggan (Phagun is the month for fructifying) exemplifies the seasonal aspect of Holi. Trees and plants start blossoming from the day of Basant and start bearing fruit by Holi.[74]

During Holi in Punjab, walls and courtyards of rural houses are enhanced with drawings and paintings similar to rangoli in South India, mandana in Rajasthan, and rural arts in other parts of India. This art is known as chowk-poorana or chowkpurana in Punjab and is given shape by the peasant women of the state. In courtyards, this art is drawn using a piece of cloth. The art includes drawing tree motifs, flowers, ferns, creepers, plants, peacocks, palanquins, geometric patterns along with vertical, horizontal and oblique lines. These arts add to the festive atmosphere.[75]

Folk theatrical performances known as swang or nautanki take place during Holi,[76] with the latter originating in the Punjab.[77] According to Self (1993), Holi fairs are held in the Punjab which may go on for many days.[78] Bose (1961) states that "in some parts of Punjab, Holi is celebrated with wrestling matches".[79]

Telangana

As in other parts of India, in rural Telangana, children celebrate kamuda and collect money, rice, corn and wood for weeks prior to Holi, and on Kamudha night all the wood is put together and set on fire.

Hindus celebrate Holi as it relates to the legend of Kama Deva. Holi is known by three names: Kamavilas, Kaman Pandigai and Kama-Dahanam[80][81][82][83]

Uttar Pradesh

Colour Drenched Gopis in Krishna Temple, Mathura, India.

Colour Drenched Gopis in Krishna Temple, Mathura, India.

A play of colours then a dance at a Hindu temple near Mathura, at Holi.

A play of colours then a dance at a Hindu temple near Mathura, at Holi.

Barsana, a town near Mathura in the Braj region of Uttar Pradesh, celebrates Lath mar Holi in the sprawling compound of the Radha Rani temple. Thousands gather to witness the Lath Mar Holi when women beat up men with sticks as those on the sidelines become hysterical, sing Holi songs and shout "Sri Radhey" or "Sri Krishna".[85] The Holi songs of Braj Mandal are sung in pure Braj, the local language. Holi celebrated at Barsana is unique in the sense that here women chase men away with sticks. Males also sing provocative songs in a bid to invite the attention of women. Women then go on the offensive and use long staves called lathis to beat the men, who protect themselves with shields.[86]

Mathura, in the Braj region, is the birthplace of Lord Krishna. In Vrindavan this day is celebrated with special puja and the traditional custom of worshipping Lord Krishna; here the festival lasts for sixteen days.[25] All over the Braj region [87] and neighboring places like Hathras, Aligarh, and Agra, Holi is celebrated in more or less the same way as in Mathura, Vrindavan and Barsana.

A traditional celebration includes Matki Phod, similar to Dahi Handi in Maharashtra and Gujarat during Krishna Janmashtami, both in the memory of god Krishna who is also called makhan chor (literally, butter thief). This is a historic tradition of the Braj region as well as the western region of India.[88] An earthen pot filled with butter or other milk products is hung high by a rope. Groups of boys and men climb on each other's shoulders to form pyramids to reach and break it, while girls and women sing songs and throw coloured water on the pyramid to distract them and make their job harder.[89] This ritual sport continues in Hindu diaspora communities.[90]

Outside Braj, in the Kanpur area, Holi lasts seven days with colour. On the last day, a grand fair called Ganga Mela or the Holi Mela is celebrated. This Mela (fair) was started by freedom fighters who fought British rule in the First Indian War of Independence in 1857 under the leadership of Nana Saheb. The Mela is held at various ghats along the banks of the River Ganga in Kanpur, to celebrate the Hindus and Muslims who together resisted the British forces in the city in 1857. On the eve of Ganga Mela, all government offices, shops, and courts generally remain closed. The Ganga Mela marks the official end of "The Festival of Colours" or Holi in Kanpur.

In Gorakhpur, the northeast district of Uttar Pradesh, the day of Holi starts with a special puja. This day, called "Holi Milan", is considered to be the most colourful day of the year, promoting brotherhood among the people. People visit every house and sing Holi songs and express their gratitude by applying coloured powder (Abeer). It is also considered the beginning of the year, as it occurs on the first day of the Hindu calendar year (Panchang).

Uttarakhand

Kumaoni Holi in Uttarakhand includes a musical affair. It takes different forms such as the Baithki Holi, the Khari Holi and the Mahila Holi. In Baithki Holi and Khari Holi, people sing songs with a touch of melody, fun, and spiritualism. These songs are essentially based on classical ragas. Baithki Holi (बैठकी होली), also known as Nirvan Ki Holi, begins from the premises of temples, where Holiyars (होल्यार) sing Holi songs and people gather to participate, along with playing classical music. The songs are sung in a particular sequence depending on the time of day; for instance, at noon the songs are based on Peelu, Bhimpalasi and Sarang ragas, while evening songs are based on the ragas such as Kalyan, Shyamkalyan and Yaman. The Khari Holi (खड़ी होली) is mostly celebrated in the rural areas of Kumaon. The songs of the Khari Holi are sung by the people, who, sporting traditional white churidar payajama and kurta, dance in groups to the tune of ethnic musical instruments such as the dhol and hurka.[91]

In the Kumaon region, the Holika pyre, known as Cheer (चीर), is ceremonially built in a ceremony known as Cheer Bandhan (चीर बंधन) fifteen days before Dulhendi. The Cheer is a bonfire with a green Paiya tree branch in the middle. The Cheer of every village and neighborhood is rigorously guarded as rival mohallas try to playfully steal each other's cheer.[92]

The colours used on Holi are derived from natural sources. Dulhendi, known as Charadi (छरड़ी) (from Chharad (छरड़)), is made from flower extracts, ash and water. Holi is celebrated with great gusto much in the same way all across North India.[93]

West Bengal

In West Bengal, Holi is known by the name of "Dol Jatra", "Dol Purnima" or the "Swing Festival". The festival is celebrated in a dignified manner by placing the icons of Krishna and Radha on a picturesquely decorated palanquin which is then taken round the main streets of the city or the village. On the Dol Purnima day in the early morning, students dress up in saffron-coloured or pure white clothes and wear garlands of fragrant flowers. They sing and dance to the accompaniment of musical instruments, such as the ektara, dubri, and Veena. The devotees take turns to swing them while women dance around the swing and sing devotional songs. During these activities, the men keep spraying coloured water and coloured powder, abir, at them.

Nepal

Preparing for Holika Dahan, Kathamandu, Nepal.

Preparing for Holika Dahan, Kathamandu, Nepal.- Locals celebrating Holi in Kathmandu, Nepal.

Two women celebrating Holi in Kathmandu, Nepal.

Two women celebrating Holi in Kathmandu, Nepal.

Holi, along with many other Hindu festivals, is celebrated in Nepal as a national festival. It is an important major Nepal-wide festival along with Dashain and Tihar (Dipawali).[94] It is celebrated in the Nepali month of Phagun (same date as Indian Holi), and signifies the legends of the Hindu god Krishna.[94] Newar Buddhists and others worship Saraswati shrine in Vajrayogini temples and celebrate the festival with their Hindu friends.[95]

Traditional concerts are held in most cities in Nepal, including Kathmandu, Narayangarh, Pokhara, Itahari, Hetauda, and Dharan, and are broadcast on television with various celebrity guests.

People walk through their neighbourhoods to celebrate Holi by exchanging colours and spraying coloured water on one another. A popular activity is the throwing of water balloons at one another, sometimes called lola (meaning water balloon).[96] Many people mix bhang in their drinks and food, as is also done during Shivaratri. It is believed that the combination of different colours at this festival takes all sorrow away and makes life itself more colourful.

Indian diaspora

Holi festival in London, UK.

Holi festival in London, UK.- Drummers of Indo-Caribbean community celebrating Phagwah (Holi) in New York City, 2013.

A celebration of Holi Festival in the United States.

A celebration of Holi Festival in the United States.

Over the years, Holi has become an important festival in many regions wherever Indian diaspora were either taken as indentured labourers during colonial era, or where they emigrated on their own, and are now present in large numbers such as in Africa, North America, Europe, Latin America, and parts of Asia such as Fiji.[17][19][97][98]

Suriname

Holi is a national holiday in Suriname. It is called Phagwa festival, and is celebrated to mark the beginning of spring and Hindu mythology. In Suriname, Holi Phagwa is a festival of colour. It is customary to wear old white clothes on this day, be prepared to get them dirty and join in the colour throwing excitement and party.[99][100]

Trinidad and Tobago

Phagwa is celebrated with a lot of colour and splendour, along with the singing on traditional Phagwah songs or Chowtal (gana).

Guyana

Phagwah is a national holiday in Guyana, and peoples of all races and religions participate in the celebrations.[101] The main celebration in Georgetown is held at the Mandir in Prashad Nagar.[102]

Fiji

Indo-Fijians celebrate Holi as festival of colours, folksongs, and dances. The folksongs sung in Fiji during Holi season are called phaag gaaian. Phagan, also written as Phalgan, is the last month of the Hindu calendar. Holi is celebrated at the end of Phagan. Holi marks the advent of spring and ripening of crops in Northern India. Not only it is a season of romance and excitement, folk songs and dances, it is also an occasion of playing with powder, perfumes, and colours. Many of the Holi songs in Fiji are around the theme of love-relationship between Radha and Krishna.[103]

Mauritius

Holi in Mauritius comes close on the heels of Shivaratri. It celebrates the beginning of spring, commemorating good harvests and the fertile land. Hindus believe it is a time of enjoying spring’s abundant colours and saying farewell to winter. It is considered one of the most exhilarating religious holidays in existence. During this event, participants hold a bonfire, throw coloured powder at each other, and celebrate wildly.[104]

United States

Holi is celebrated in many US states. It is usually hosted in temples or cultural halls. Members of Hindu associations and volunteers assist in hosting the event along with temple devotees. Some of the places known to celebrate Holi are New Brunswick (NJ), Spanish Fork (Utah), Houston (TX), Dallas (TX), South El Monte (CA), Milpitas (CA), Boston (MA), Potomac (MD), and Chicago (IL).[105]

Indonesia

In Indonesia, Indian Indonesians and Hindu peoples celebrate Holi as festival of colours. The main celebrations in Medan and Bali.[106]

Pakistan

Holi is celebrated by the minority Hindu population in Pakistan. Community events by Hindus have been reported by Pakistani media in various cities such as Karachi,[107] Hazara,[108] Rawalpindi, Sindh, Hyderabad, Multan and Lahore.[109]The Hindu tribes of Cholistan in the Punjab province of Pakistan play the game called Khido in the days leading up to the Holi.The game Khido is considered sacred by them as it is believed that Parhlad used to play this game during his childhood.[110]

Holi was not a public holiday in Pakistan from 1947 to 2016. Holi along with Diwali for Hindus, and Easter for Christians, was adopted as public holiday resolution by Pakistan's parliament in 2016, giving the local governments and public institutions the right to declare Holi as a holiday and grant leave for its minority communities, for the first time.[111] This decision has been controversial, with some Pakistanis welcoming the decision, while others criticising it, with the concern that declaring Holi a public holiday advertises a Hindu festival to Pakistani children.[112]

Holi colours

_flowers_in_Kolkata_W_IMG_4219.jpg)

Traditional sources of colours

The spring season, during which the weather changes, is believed to cause viral fever and cold. The playful throwing of natural coloured powders, called gulal has a medicinal significance: the colours are traditionally made of neem, kumkum, haldi, bilva, and other medicinal herbs prescribed by Āyurvedic doctors.

Many colours are obtained by mixing primary colours. Artisans produce and sell many of the colours from natural sources in dry powder form, in weeks and months preceding Holi. Some of the traditional natural plant-based sources of colours are:[12][113][114]

Orange and red

The flowers of palash or tesu tree, also called the flame of the forest, are typical source of bright red and deep orange colours. Powdered fragrant red sandalwood, dried hibiscus flowers, madder tree, radish, and pomegranate are alternate sources and shades of red. Mixing lime with turmeric powder creates an alternate source of orange powder, as does boiling saffron (kesar) in water.

Green

Mehendi and dried leaves of gulmohur tree offer a source of green colour. In some areas, the leaves of spring crops and herbs have been used as a source of green pigment.

Yellow

Haldi (turmeric) powder is the typical source of yellow colour. Sometimes this is mixed with chickpea (gram) or other flour to get the right shade. Bael fruit, amaltas, species of chrysanthemums, and species of marigold are alternate sources of yellow.

Blue

Indigo plant, Indian berries, species of grapes, blue hibiscus, and jacaranda flowers are traditional sources of blue colour for Holi.

Magenta and purple

Beetroot is the traditional source of magenta and purple colour. Often these are directly boiled in water to prepare coloured water.

Brown

Dried tea leaves offer a source of brown coloured water. Certain clays are alternate source of brown.

Black

Species of grapes, fruits of amla (gooseberry) and vegetable carbon (charcoal) offer gray to black colours.

Synthetic colours

Natural colours were used in the past to celebrate Holi safely by applying turmeric, sandalwood paste, extracts of flowers and leaves. As the spring-blossoming trees that once supplied the colours used to celebrate Holi have become rarer, chemically produced industrial dyes have been used to take their place in almost all of urban India. Due to the commercial availability of attractive pigments, slowly the natural colours are replaced by synthetic colours. As a result, it has caused mild to severe symptoms of skin irritation and inflammation. Lack of control over the quality and content of these colours is a problem, as they are frequently sold by vendors who do not know their source.

Holi powder

Health Impact

A 2007 study found that malachite green, a synthetic bluish-green dye used in some colours during Holi festival, was responsible for severe eye irritation in Delhi, if eyes were not washed upon exposure. Though the study found that the pigment did not penetrate through the cornea, malachite green is of concern and needs further study.[115]

Another 2009 study reports that some colours produced and sold in India contain metal-based industrial dyes, causing an increase in skin problems to some people in the days following Holi. These colours are produced in India, particularly by small informal businesses, without any quality checks and are sold freely in the market. The colours are sold without labeling, and the consumer lacks information about the source of the colours, their contents, and possible toxic effects. In recent years, several nongovernmental organisations have started campaigning for safe practices related to the use of colours. Some are producing and marketing ranges of safer colours derived from natural sources such as vegetables and flowers.[116]

These reports have galvanised a number of groups into promoting more natural celebrations of Holi. Development Alternatives, Delhi's CLEAN India campaign[117], Kalpavriksh Environment Action Group, Pune[118], Society for Child Development through its Avacayam Cooperative Campaign[119] have launched campaigns to help children learn to make their own colours for Holi from safer, natural ingredients. Meanwhile, some commercial companies such as the National Botanical Research Institute have begun to market "herbal" dyes, though these are substantially more expensive than the dangerous alternatives. However, it may be noted that many parts of rural India have always resorted to natural colours (and other parts of festivities more than colours) due to availability.

In urban areas, some people wear nose masks and sunglasses to avoid inhaling pigments and to prevent chemical exposure to eyes.[120]

Environmental impact

An alleged environmental issue related to the celebration of Holi is the traditional Holika bonfire, which is believed to contribute to deforestation. Activists estimate Holika causes 30,000 bonfires every year, with each one burning approximately 100 kilograms (220.46 lbs) of wood.[121] This represents less than 0.0001% of 350 million tons of wood India consumes every year, as one of the traditional fuels for cooking and other uses.[122]

The use of heavy metal-based pigments during Holi is also reported to cause temporary wastewater pollution, with the water systems recovering to pre-festival levels within 5 days.[123]

Flammability

During traditional Holi celebrations in India, Rinehart writes, colours are exchanged in person by "tenderly applying coloured powder to another person's cheek", or by spraying and dousing others with buckets of coloured water.[124]

Influence on other cultures

Holi is celebrated as a social event in parts of the United States.[125] For example, at Sri Sri Radha Krishna Temple in Spanish Fork, Utah, NYC Holi Hai in Manhattan, New York[126] and Festival of Colors: Holi NYC in New York City, New York,[125][127] Holi is celebrated as the Festival of Color, where thousands of people gather from all over the United States, play and mingle.[4][125][128]

Holi-inspired events

A number of Holi-inspired social events have also surfaced, particularly in Europe and the United States, often organised by companies as for-profit or charity events with paid admission, and with varying scheduling that does not coincide with the actual Holi festival. These have included Holi-inspired music festivals such as the Festival Of Colours Tour and Holi One[129] (which feature timed throws of Holi powder), and 5K run franchises such as The Color Run, Holi Run and Color Me Rad,[130] in which participants are doused with the powder at per-kilometre checkpoints.[131][132] The BiH Color Festival is a Holi-inspired electronic music festival held annually in Brčko, Bosnia and Herzegovina.[133][134]

There have been concerns that these events appropriate and trivialise aspects of Holi for commercial gain—downplaying or completely ignoring the cultural and spiritual roots of the celebration.[131][132] Organisers of these events have argued that the costs are to cover various key aspects of their events, such as safe colour powders, safety and security, and entertainment.[132]

See also

- Midsummer – Holiday associated with the summer solstice and feast day of Saint John the Baptist

- Nowruz – Day of new year in the Persian and Zoroastrian calendars

- Songkran (Thailand) – Traditional Thai New Year's holiday

Notes

- Since ancient times, the Indian subcontinent has had several major Hindu calendars, which places Holi and other festivals on different local months even though they mean the same date. Some Hindu calendars emphasise the solar cycle, some the lunar cycle. Further, the regional calendars feature two traditions of Amanta and Purnimanta systems, wherein the similar-sounding months refer to different parts of a lunar cycle, thus further diversifying the nomenclature. The Hindu festival of Holi falls on the first (full moon) day of Chaitra lunar month's dark fortnight in the Purnimanta system, while the same exact day for Holi is expressed in Amanta system as the lunar day of Phalguna Purnima.[47] Both time measuring and dating systems are equivalent ways of meaning the same thing, they continue to be in use in different regions.[47][48] In regions where the local calendar places it in its Phalguna month, Holi is also called Phaguwa.

References

- The New Oxford Dictionary of English (1998) ISBN 0-19-861263-X p. 874 "Holi /'həʊli:/ noun a Hindu spring festival ...".

- Kristi L. Wiley (2009). The A to Z of Jainism. Scarecrow. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-8108-6337-8.

- Bal Gopal Shrestha (2012). The Sacred Town of Sankhu: The Anthropology of Newar Ritual, Religion and Society in Nepal. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 269–271, 240–241. ISBN 978-1-4438-3825-2.

- Lyford, Chris (5 April 2013). "Hindu spring festivals increase in popularity and welcome non-Hindus". The Washington Post. New York City. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

Despite what some call the reinvention of Holi, the simple fact that the festival has transcended cultures and brings people together is enough of a reason to embrace the change, others say. In fact, it seems to be in line with many of the teachings behind Holi festivals.

- Holi: Splashed with colors of friendship Hinduism Today, Hawaii (2011)

- "National Portal of India". www.india.gov.in. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- "National Portal of India". www.india.gov.in. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- Yudit Greenberg, Encyclopedia of Love in World Religions, Volume 1, ISBN 978-1851099801, p. 212

- McKim Marriott (2006). John Stratton Hawley and Vasudha Narayanan (ed.). The Life of Hinduism. University of California Press. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-520-24914-1., Quote: "Holi, he said with a beatific sigh, is the Festival of Love!"

- What Is Hinduism?. Himalayan Academy Publications. 2007. p. 230. ISBN 978-1-934145-27-2.

- "Festivals for Spring: Holi and Basant Kite Festival: Holi".

Holi celebrates love, forgiveness, and triumph of good over evil

- Ebeling, Karin (2010), Holi, an Indian Festival, and its Reflection in English Media; Die Ordnung des Standard und die Differenzierung der Diskurse: Akten des 41. Linguistischen Kolloquiums in Mannheim 2006, 1, 107, ISBN 978-3631599174

- Wendy Doniger (Editor), Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of World Religions, 2000, ISBN 978-0877790440, Merriam-Webster, p. 455

- "About Holi – Dhuleti Colorful Spring Festival". Holi Dhuleti Celebrations. Archived from the original on 29 March 2016. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- Helen Myers (1998). Music of Hindu Trinidad: Songs from the India Diaspora. University of Chicago Press. p. 430. ISBN 978-0-226-55453-2.

- Amber Wilson (2004). Jamaica: The people. Crabtree Publishing Company. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-7787-9331-1.

- Holi Festivals Spread Far From India The Wall Street Journal (2013)

- A Spring Celebration of Love Moves to the Fall – and Turns Into a Fight Gabriele Steinhauser, The Wall Street Journal (3 October 2013)

- Holi Festival of Colours Visit Berlin, Germany (2012)

- Constance Jones, Holi, in J Gordon Melton (Editor), Religious Celebrations: An Encyclopedia of Holidays Festivals Solemn Observances and Spiritual Commemorations, ISBN 978-1598842067

- Victoria Williams (2016). Celebrating Life Customs around the World. ABC-CLIO. p. 75. ISBN 978-1-4408-3659-6.

- Ayyagari, Shalini (2007). ""Hori Hai": A Festival of Colours!! (review)". Asian Music. Johns Hopkins University Press. 38 (2): 151–153. doi:10.1353/amu.2007.0029.

- "High on Holi with bhang". The Times of India. Retrieved 26 March 2014.

- Holi India Heritage: Culture, Fairs and Festivals (2008)

- Holi – the festival of colours Archived 1 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine The Indian Express.

- The Legend of Radha-Krishna, Society for the Confluence of Festivals in India (2009)

- R Deepta, A.K. Ramanujan's ‘Mythologies’ Poems: An Analysis, Points of View, Volume XIV, Number 1, Summer 2007, pp. 74–81

- Lynn Peppas (2010), Holi, Crabtree Publishing, ISBN 978-0-7787-4771-0, pp. 12–15

- The arrival of Phagwa - Holi Archived 12 April 2018 at the Wayback Machine The Guardian, Trinidad and Tobago (12 March 2009)

- Eat, Pray, SmearEat, Pray, Smear Julia Moskin, New York Times (22 March 2011)

- Holi in Mauritius. "Just as the many other major Hindu festivals, the large Indian majority.. celebrate Holi with a lot of enthusiasm in the island of Mauritius. It is an official holiday in the country..."

- David N. Lorenzen (1996). Praises to a Formless God: Nirguni Texts from North India. State University of New York Press. pp. 22–31. ISBN 978-0-7914-2805-4.

- Vittorio Roveda (2005). Images of the Gods: Khmer Mythology in Cambodia, Thailand and Laos. River Books. p. 70. ISBN 978-974-9863-03-9.;

Sunil Kothari; Avinash Pasricha (2001). Kuchipudi. Abhinav. pp. 66–67. ISBN 978-81-7017-359-5. - Roshen Dalal (2010). Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. Penguin Books India. p. 275. ISBN 978-0-14-341421-6.

- Robin Rinehart (2004). Contemporary Hinduism: Ritual, Culture, and Practice. ABC-CLIO. pp. 135–137. ISBN 978-1-57607-905-8.

- Michelle Lee (2016). Holi. Scobre. pp. 8–11. ISBN 978-1-62920-572-4.

- Usha Sharma (2008). Festivals In Indian Society. Mittal Publications. pp. 80–82. ISBN 978-81-8324-113-7.

- Safvi, Rana (23 March 2016). "In Mughal India, Holi was celebrated with the same exuberance as Eid". Scroll.in. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- Sharma, Sunit (2017) Mughal Arcadia: Persian Literature in an Indian Court. Harvard University Press

- Powers, Janet M. (30 November 2008). Kites over the Mango Tree: Restoring Harmony between Hindus and Muslims in Gujarat: Restoring Harmony between Hindus and Muslims in Gujarat. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-35158-7.

- W. H. McLeod (2009). The A to Z of Sikhism. Scarecrow Press. p. 95. ISBN 978-0-8108-6344-6.

- Christian Roy (2005). Traditional Festivals: A Multicultural Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 192–193. ISBN 978-1-57607-089-5.

- James K. Wellman Jr.; Clark Lombardi (2012). Religion and Human Security: A Global Perspective. Oxford University Press. pp. 112 note 18. ISBN 978-0-19-982775-6.

- Nikky-Guninder Kaur Singh (2011). Sikhism: An Introduction. I.B.Tauris. pp. 93–94. ISBN 978-1-84885-321-8.

- Peter J. Claus; Sarah Diamond; Margaret Ann Mills (2003). South Asian Folklore: An Encyclopedia : Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka. Taylor & Francis. p. 552. ISBN 978-0-415-93919-5.

- Holi on Canvas, The Sunday Tribune Holi on Canvas, Kanwarjit Singh Kang, 13 March 2011

- Christopher John Fuller (2004). The Camphor Flame: Popular Hinduism and Society in India. Princeton University Press. pp. 291–293. ISBN 978-0-69112-04-85.

- Nachum Dershowitz; Edward M. Reingold (2008). Calendrical Calculations. Cambridge University Press. pp. 123–133, 275–311. ISBN 978-0-521-88540-9.

- Javier A. Galván (2014). They Do What? A Cultural Encyclopedia of Extraordinary and Exotic Customs from around the World. ABC-CLIO. pp. 137–138. ISBN 978-1-61069-342-4.

- J. Gordon Melton; Martin Baumann (2010). Religions of the World: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Beliefs and Practices, 2nd Edition. ABC-CLIO. pp. 1337–1338. ISBN 978-1-59884-204-3.

- Andrew Smith (2013). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Food and Drink in America. Oxford University Press. p. 185. ISBN 978-0-19-973496-2.

- Holi Festival see Play of Colors (2009)

- Rangapanchami in Bhopal Los Angeles Times (2011)

- Religions – Hinduism: Holi. BBC. Retrieved 21 March 2011.

- Rituals of Holi Society for the Confluence of Festivals in India (2010)

- Holi Festival Rex Li Indrajeet Deshmukh and Marielle Roth, Festival Circle, IDSS 2013

- Holi 2013 Ankita Mehta, International Business Times, (22 March 2013)

- "Holi Milan". indiacitytrip.com.

- "Holi 2014: Festival Of Colors Celebrates Spring (Songs, Photos)". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 17 March 2014.

- Guṅe, Viṭhṭhala Triṃbaka (1979). Gazetteer of the Union Territory Goa, Daman and Diu: district. 1. Goa, Daman and Diu (India). Gazetteer Dept. p. 263.

- "You are being redirected..." pndwarka.com.

- topnews.in, Holi in Gujarat

- "Holi celebration in Jammu and Kashmir". holifestival.org.

- "Karnataka". The Hindu. 10 March 2009. Retrieved 23 September 2013.

- "Elevation of the black stone arch". V&A: Search the Collections. Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 10 April 2016.

Object history note: The arch is covered with figures of Vaishnavite gods and hung with rings. A crowd of Hindus are celebrating the festival of the Dol Jatra or Swing festival in which the image of Vishnu and his consort are swung in a throne suspended by chains from the rings of the arch. The celebration is part of the Holi festival and takes place at the full moon of the month of Phalguna (February to March).

- Dipti Ray (2007). Prataparudradeva, the Last Great Suryavamsi King of Orissa (A.D. 1497 to A.D. 1540). Northern Book Centre. pp. 90–. ISBN 978-81-7211-195-3.

- Biswamoy Pati (2001). Situating Social History: Orissa, 1800-1997. Orient Blackswan. pp. 74–. ISBN 978-81-250-2007-3.

- A dictionary of the Panjábí language (1854) Mission Press

- Sekhon, Iqbal Singh (2000) The Punjabis. 2. Religion, society, and culture of the Punjabis. COSMOS

- Proceedings – Punjab History Conference (2000) Publication Bureau, Punjabi University

- Bose, Nirmal Kumar (1929) Cultural Anthropology: And Other Essays. [Reprinted with Additions]Indian Associated Publishing Company, Limited

- Parminder Singh Grover and Moga, Davinderjit Singh, Discover Punjab: Attractions of Punjab

- Jasbir Singh Khurana, Punjabiyat: The Cultural Heritage and Ethos of the People of Punjab, Hemkunt Publishers (P) Ltd., ISBN 978-81-7010-395-0

- Census of India, 1961: Punjab. Manager of Publications

- Drawing Designs on Walls, Trisha Bhattacharya (13 October 2013), Deccan Herald. Retrieved 7 January 2015

- Alka Pande (1999) Folk Music & Musical Instruments of Punjab: From Mustard Fields to Disco Lights, Volume 1. Mapin Pub

- Nandini Gooptu (2001) The Politics of the Urban Poor in Early Twentieth-Century India. Cambridge University Press.

- Self, David (1993) One Hundred Readings for Assembly. Heinemann

- Bose, Nirmal Kumar (1961) Cultural Anthropology. Asia Publishing House

- M. Arunachalam (1980). Festivals of Tamil Nadu. Gandhi Vidyalayam. pp. 242–244.

- K. Gnanambal (1947). Home Life Among the Tamils in the Sangam Age. Central Art Press. p. 98.

- G. Rajagopal (2007). Beyond Bhakti: Steps Ahead. B.R. Publishing. p. 75. ISBN 978-81-7646-510-6.

- "Holi in Tamil Nadu". holifestival.org. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- Lathmar Holi Festival Lane Turner, Boston Globe, (5 March 2012)

- "Play Holi Song".

- "ganga Mela Kanpur". bhaskar.com. 27 March 2016.

- "So drop colors – Holi, Brij Lal was". jagran. 19 March 2014.

- David Gellner (2009). Ethnic Activism and Civil Society in South Asia. SAGE Publications. pp. 27–29. ISBN 978-81-321-0422-3.

- Tradition of Holi, Society for the Confluence of Festivals in India (2016)

- Indo American News, Volume 33, No. 14, 4 April 2014, p. 5

- "kumaoni Holi Uttrakhand". euttarakhand.com. 4 March 2015.

- "kumaoni holi". euttarakhand.com. 4 March 2015.

- Kumaoni Holi – Uttaranchal Fairs and Festivals. Euttaranchal.com. Retrieved 21 March 2011.

- William Brook Northey; C. J. Morris (2001). The Gurkhas: Their Manners, Customs, and Country. Asian Educational Services. pp. 79–80. ISBN 978-81-206-1577-9.

- Bal Gopal Shrestha (2012). The Sacred Town of Sankhu: The Anthropology of Newar Ritual, Religion and Society in Nepal. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 269, 240–241, 283–284. ISBN 978-1-4438-3825-2.

- Happy Holi week Archived 23 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Nepali Times. Retrieved 21 March 2011.

- Holi Festival 2013 Archived 24 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine Community Center of Gujarati Samaj, New York (2013)

- Celebrate Holi: Durban South Africa (2013)

- Holi Phagwa Suriname Insider (2012)

- Phagwa – Festival of Colors Archived 14 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine Independence Square in Paramaribo, Suriname (2013)

- Ali, Arif (ed.), Guyana London: Hansib, 2008, p. 69

- Smock, Kirk, Guyana: the Bradt Travel Guide, 2007, p. 24.

- Holi, festival of colours The Fiji Times (15 March 2011)

- Holi Festival Archived 6 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine Mauritius (2011)

- "Holi celebration in abroad". holifestival.org.

- "Warna-warni Festival Holi di Denpasar Bali". kumparan.

- Soaked in mirth and colour, Hindu community celebrates Holi, Sarah Munir (28 March 2013) Tribune. Retrieved 7 January 2015

- 'Holi ayi, Holi ayi': Hindus in Hazara celebrate the arrival of spring, the festival of love (17 March 2014) Tribune. Retrieved 7 January 2015

- Holi celebrations in Pakistan, (17 March 2014) Dawn. Retrieved 7 January 2015

- "The Colours of Holi with the Hindus of Cholistan". Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- Pakistan parliament adopts resolution for Holi, Diwali, Easter holidays, The Times of India (16 March 2016)

- How the public holiday on Holi underscores bigotry in Pakistan, Dawn, Sadia Khartoum (12 May 2016), Quote: "Today we are announcing a public holiday for Holi, tomorrow we will be telling everyone to read Ramayana!’” PSMA Chairman Sharafuz Zaman says(...) If someone wants to go play Holi, they can go ahead, Zaman goes on, but by declaring it a public holiday, we have advertised it in every home."

- Holi colors Society for the Confluence of Festivals in India (2009)

- Celebration powders (Gulal/Holi) Purcolor (2010)

- Velpandian, T.; Saha, K.; Ravi, A.K.; Kumari, S.S.; Biswas, N.R.; Ghose, S. (2007). "Ocular hazards of the colors used during the festival-of-colors (Holi) in India—Malachite green toxicity". Journal of Hazardous Materials. 139 (2): 204–208. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2006.06.046. PMID 16904259.

- Ghosh, S. K., Bandyopadhyay, D., Chatterjee, G., & Saha, D. (2009), The ‘Holi’ dermatoses: Annual spate of skin diseases following the spring festival in India. Indian journal of dermatology. 54(3), 240

- "CLEAN India campaign". Archived from the original on 23 April 2013.

- "The safe Holi campaign". Archived from the original on 26 March 2007.

- "Society For Child Development". Sfcdindia.org. Retrieved 23 September 2013.

- Holi Festival Archived 3 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine What to wear? UK (2012)

- "No real attempt to save trees". The Times of India. 17 March 2003.

- Swaminathan and Varadharaj, The status of firewood in India, IUFRO Symposium Proceedings (2003), pp. 150–156

- Tyagi, V. K., Bhatia, A., Gaur, R. Z., Khan, A. A., Ali, M., Khursheed, A., & Kazmi, A. A. (2012), Effects of multi-metal toxicity on the performance of sewage treatment system during the festival of colours (Holi) in India, Environmental monitoring and assessment, 184(12), pp. 7517–7529

- Rinehart, Robin (2004). Contemporary Hinduism ritual, culture, and practice. p. 137. ISBN 978-1-57607-905-8.

- "Festival of Colors – Holi NYC 2016". Festival of Colors: Holi NYC.

- "NYC Holi Hai 2016".

- Spinelli, Lauren; Editors, Time Out (9 May 2015). "Check out the multi-colored fun at this year's Holi party". Time Out New York. New York City. Archived from the original on 14 May 2015. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

Ker-pow! Just when you thought spring couldn't look any more spectacular, Brooklyn hosted its annual Festival of Colors celebration at the Cultural Performing Arts Center (May 9). Partygoers flung paint powder around with gleeful abandon while grooving the day and night away, and as you'll see from our photos, this year's bash was one of the most gloriously messy spring events in NYC.

CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link) - Muncy, C.S. (4 May 2014). "Portraits From Holi NYC". The Village Voice. New York City. Archived from the original on 1 August 2015. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

Holi Hai, also known as the Festival of Colors, celebrates the coming of spring, the joy of friendship, and equality for all. Held on Saturday, May 3, 2014 at the Yard @ C-PAC (Cultural Performing Arts Center) in Brooklyn, thousands of participants joined in to dance and generally cover each other in colored powder. The powders used in Holi represent happiness, love, and the freedom to live vibrantly.

- "Welcome to HOLI ONE". Holi One. Birmingham, England. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

Thousands of people, dressed in white, come together to share in music, dance, performance art and visual stimulation. Holi One brings this unforgettable experience to cities all around the world.

- "Color Me Rad 5K Run". SanJose.com. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- "Hindu Holi festival shows its colours in UK". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- "A Spring Celebration of Love Moves to the Fall – and Turns Into a Fight". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- "Oboji svoje ljeto uz BiH Color Festival 28. i 29. jula u Brčkom" (in Bosnian). 6yka.com. 13 July 2017.

- "BiH Color Festival po drugi put u Brčkom" (in Bosnian). otisak.ba. 25 July 2017. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

External links

- Holi at Curlie

- Holi – Festival of Colours Government of Goa, India