Azadirachta indica

Azadirachta indica, commonly known as neem, nimtree or Indian lilac,[3] is a tree in the mahogany family Meliaceae. It is one of two species in the genus Azadirachta, and is native to the Indian subcontinent. It is typically grown in tropical and semi-tropical regions. Neem trees also grow in islands located in the southern part of Iran. Its fruits and seeds are the source of neem oil.

| Neem | |

|---|---|

_in_Hyderabad_W_IMG_6976.jpg) | |

| Flowers and leaves | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Sapindales |

| Family: | Meliaceae |

| Genus: | Azadirachta |

| Species: | A. indica |

| Binomial name | |

| Azadirachta indica | |

| Synonyms[2][3] | |

| |

Description

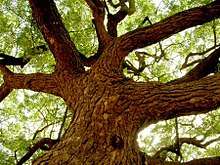

Neem is a fast-growing tree that can reach a height of 15–20 metres (49–66 ft), and rarely 35–40 metres (115–131 ft). It is evergreen, but in severe drought it may shed most or nearly all of its leaves. The branches are wide and spreading. The fairly dense crown is roundish and may reach a diameter of 20–25 metres (66–82 ft). The neem tree is very similar in appearance to its relative, the Chinaberry (Melia azedarach).[4]

The opposite, pinnate leaves are 20–40 centimetres (7.9–15.7 in) long, with 20 to 30 medium to dark green leaflets about 3–8 centimetres (1.2–3.1 in) long. The terminal leaflet often is missing. The petioles are short.

The (white and fragrant) flowers are arranged in more-or-less drooping axillary panicles which are up to 25 centimetres (9.8 in) long. The inflorescences, which branch up to the third degree, bear from 250 to 300 flowers. An individual flower is 5–6 millimetres (0.20–0.24 in) long and 8–11 millimetres (0.31–0.43 in) wide. Protandrous, bisexual flowers and male flowers exist on the same individual tree.

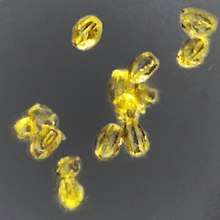

The fruit is a smooth (glabrous), olive-like drupe which varies in shape from elongate oval to nearly roundish, and when ripe is 1.4–2.8 centimetres (0.55–1.10 in) by 1.0–1.5 centimetres (0.39–0.59 in). The fruit skin (exocarp) is thin and the bitter-sweet pulp (mesocarp) is yellowish-white and very fibrous. The mesocarp is 0.3–0.5 centimetres (0.12–0.20 in) thick. The white, hard inner shell (endocarp) of the fruit encloses one, rarely two, or three, elongated seeds (kernels) having a brown seed coat.

The neem tree is often confused with a similar looking tree called bakain. Bakain also has toothed leaflets and similar looking fruit. One difference is that neem leaves are pinnate but bakain leaves are twice- and thrice-pinnate.

Ecology

The neem tree is noted for its drought resistance. Normally it thrives in areas with sub-arid to sub-humid conditions, with an annual rainfall of 400–1,200 millimetres (16–47 in). It can grow in regions with an annual rainfall below 400 mm, but in such cases it depends largely on ground water levels. Neem can grow in many different types of soil, but it thrives best on well drained deep and sandy soils. It is a typical tropical to subtropical tree and exists at annual mean temperatures of 21–32 °C (70–90 °F). It can tolerate high to very high temperatures and does not tolerate temperature below 4 °C (39 °F). Neem is one of a very few shade-giving trees that thrive in drought-prone areas e.g. the dry coastal, southern districts of India, and Pakistan. The trees are not at all delicate about water quality and thrive on the merest trickle of water, whatever the quality. In India and tropical countries where the Indian diaspora has reached, it is very common to see neem trees used for shade lining streets, around temples, schools and other such public buildings or in most people's back yards. In very dry areas the trees are planted on large tracts of land.

Weed status

Neem is considered a weed in many areas, including some parts of the Middle East, most of Sub-Saharan Africa including West Africa and Indian Ocean states, and some parts of Australia. Ecologically, it survives well in similar environments to its own, but its weed potential has not been fully assessed.[8]

In April 2015, A. indica was declared a class B and C weed in the Northern Territory, Australia, meaning its growth and spread must be controlled and plants or propagules are not allowed to be brought into the NT. It is illegal to buy, sell, or transport the plants or seeds. Its declaration as a weed came in response to its invasion of waterways in the "Top End" of the territory.[9]

After being introduced into Australia, possibly in the 1940s, A. indica was originally planted in the Northern Territory to provide shade for cattle. Trial plantations were established between the 1960s and 1980s in Darwin, Queensland, and Western Australia, but the Australian neem industry did not prove viable. The tree has now spread into the savanna, particularly around waterways, and naturalised populations exist in several areas.[10]

Uses

.jpg)

Neem leaves are dried in India and placed in cupboards to prevent insects eating the clothes, and also in tins where rice is stored.[11] These flowers are also used in many Indian festivals like Ugadi. See below: #Association with Hindu festivals in India. As an ayurvedic herb, neem is also used in baths.

As a vegetable

The tender shoots and flowers of the neem tree are eaten as a vegetable in India. A souplike dish called Veppampoo charu (Tamil) (translated as "neem flower rasam") made of the flower of neem is prepared in Tamil Nadu. In Bengal, young neem leaves are fried in oil with tiny pieces of eggplant (brinjal). The dish is called neem begun bhaja and is the first item during a Bengali meal that acts as an appetizer. It is eaten with rice.[12]

Neem is used in parts of mainland Southeast Asia, particularly in Cambodia aka sdov—ស្ដៅវ,[13] Laos (where it is called kadao), Thailand (where it is known as sa-dao (สะเดา) or sdao), Myanmar (where it is known as tamar) and Vietnam (where it is known as sầu đâu and is used to cook the salad gỏi sầu đâu). Even if lightly cooked, the flavour is quite bitter and the food is not enjoyed by all inhabitants of these nations, though it is believed to be good for one's health. Neem gum is a rich source of protein. In Myanmar, young neem leaves and flower buds are boiled with tamarind fruit to soften its bitterness and eaten as a vegetable. Pickled neem leaves are also eaten with tomato and fish paste sauce in Myanmar.

Traditional medicinal use

Products made from neem trees have been used in India for over two millennia for their medicinal properties.[11] Neem products are believed by Siddha and Ayurvedic practitioners to be anthelmintic, antifungal, antidiabetic, antibacterial, contraceptive, and sedative.[14] It is considered a major component in Siddha medicine and Ayurvedic and Unani medicine and is particularly prescribed for skin diseases.[15] Neem oil is also used for healthy hair, to improve liver function, detoxify the blood, and balance blood sugar levels.[16] Neem leaves have also been used to treat skin diseases like eczema, psoriasis, etc.[11]

Insufficient research has been done to assess the purported benefits of neem, however.[17] In adults, short-term use of neem is safe, while long-term use may harm the kidneys or liver; in small children, neem oil is toxic and can lead to death.[17] Neem may also cause miscarriages, infertility, and low blood sugar.[17]

Safety issues

Neem oil and leaves have the ability to cause some forms of toxic encephalopathy and ophthalmopathy if consumed in any quantity.[18]

Pest and disease control

Neem is a key ingredient in non-pesticidal management (NPM), providing a natural alternative to synthetic pesticides. Neem seeds are ground into powder that is soaked overnight in water and sprayed onto the crop. To be effective, it must be applied repeatedly, at least every ten days. Neem does not directly kill insects on the crop. It acts as an anti-feedant, repellent, and egg-laying deterrent and thus protect the crop from damage. The insects starve and die within a few days. Neem also suppresses the hatching of pest insects from their eggs. Neem-based fertilizeres have been effective against the pest southern armyworm. Neem cake is often sold as a fertilizer.[19]

Neem oil has been shown to avert termite attack as an ecofriendly and economical agent.[20]

Neem oil for polymeric resins

Applications of neem oil in the preparation of polymeric resins have been documented in the recent reports. The synthesis of various alkyd resins from neem oil is reported using a monoglyceride (MG) route and their utilization for the preparation of PU coatings.[21] The alkyds are prepared from reaction of conventional divalent acid materials like phthalic and maleic anhydrides with MG of neem oil.

Construction

The juice of this plant is a potent ingredient for a mixture of wall plaster, according to the Samarāṅgaṇa Sūtradhāra, which is a Sanskrit treatise dealing with Śilpaśāstra (Hindu science of art and construction).[22]

Other uses

- Toothbrush: Traditionally, slender neem twigs (called datun) are first chewed as a toothbrush and then split as a tongue cleaner.[23] This practice has been in use in India, Africa, and the Middle East for centuries. It is still used in India's rural areas. Neem twigs are still collected and sold in rural markets for this use. It has been found to be as effective as a toothbrush in reducing plaque and gingival inflammation.[24][25]

- Tree: Besides its use in traditional Indian medicine, the neem tree is of great importance for its anti-desertification properties and possibly as a good carbon dioxide sink.[26][27]

- Fertilizer: Neem extract is added to fertilizers (urea) as a nitrification inhibitor.[28]

- Soap: 80% of India's supply of neem oil now is used by neem oil soap manufacturers.[29] Although much of it goes to small-scale speciality soaps, often using cold-pressed oil, large-scale producers also use it, mainly because it is cheap. Additionally it is antibacterial and antifungal, soothing, and moisturising. It can be made with up to 40% neem oil.[29] Generally, the crude oil is used to produce coarse laundry soaps.

- Animal feed: Neem leaves can be occasionally used as forage for ruminants and rabbits.[30]

Association with Hindu festivals in India

Neem leaf or bark is considered an effective pitta pacifier because of its bitter taste. Hence, it is traditionally recommended during early summer in Ayurveda (that is, the month of Chaitra as per the Hindu Calendar which usually falls in the month of March – April).

In the Indian states of Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka and Telangana, Neem flowers are very popular for their use in 'Ugadi Pachhadi' (soup-like pickle), which is made on Ugadi day. In Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, and Telangana, a small amount of Neem and Jaggery (Bevu-Bella) is consumed on Ugadi day, the Telugu and Kannada new year, indicating that one should take both bitter and sweet things in life, joy and sorrow.

During Gudi Padva, which is the New Year in the state of Maharashtra, the ancient practice of drinking a small quantity of neem juice or paste on that day, before starting festivities, is found. As in many Hindu festivals and their association with some food to avoid negative side-effects of the season or change of seasons, neem juice is associated with Gudi Padva to remind people to use it during that particular month or season to pacify summer pitta.

In Tamil Nadu during the summer months of April to June, the Mariamman temple festival is a thousand-year-old tradition. The Neem leaves and flowers are the most important part of the Mariamman festival. The statue of the goddess Mariamman will be garlanded with Neem leaves and flowers. Thus, it is regarded as holy leaves. During most occasions of celebrations and weddings the people of Tamil Nadu adorn their surroundings with the Neem leaves and flowers as a form of decoration and also to ward off evil spirits and infections. The Tamil people traditionally consider that the various diseases of pox and measles are caused directly by the deity Mariamman herself and use the Neem leaves alone to relieve from infection.

In the eastern coastal state of Odisha the famous Jagannath temple deities are made up of Neem heart wood along with some other essential oils and powders.

Chemical compounds

Ayurveda was the first to bring the anthelmintic, antifungal, antibacterial, and antiviral constituents of the neem tree to the attention of natural products chemists. The process of extracting neem oil involves extracting the water-insoluble components with ether, petrol ether, ethyl acetate, and dilute alcohol. The provisional naming was nimbin (sulphur-free crystalline product with melting point at 205 °C, empirical composition C7H10O2), nimbinin (with similar principle, melting at 192 °C), and nimbidin (cream-coloured containing amorphous sulphur, melting at 90–100 °C). Siddiqui identified nimbidin as the main active antibacterial ingredient, and the highest yielding bitter component in the neem oil.[31] These compounds are stable and found in substantial quantities in the neem. They also serve as natural insecticides.[32]

Neem-coated urea is being used an alternate to plain urea fertilizer in India. It reduces pollution, improves fertilizer's efficacy and soil health.[33][34]

Genome and transcriptomes

Neem genome and transcriptomes from various organs have been sequenced, analyzed, and published by Ganit Labs in Bangalore, India.[35][36][37]

ESTs were identify by generation of subtractive hybridization libraries of neem fruit, leaf, fruit mesocarp, and fruit endocarp by CSIR-CIMAP Lucknow.[38][39]

Cultural and social impact

The name "Nimai", a reference to this legend, means "of the neem tree" and trends at 5–10 babies per million.[40]

In 1995, the European Patent Office (EPO) granted a patent on an anti-fungal product derived from neem to the United States Department of Agriculture and W. R. Grace and Company.[41] The Indian government challenged the patent when it was granted, claiming that the process for which the patent had been granted had been in use in India for more than 2,000 years. In 2000, the EPO ruled in India's favour, but W. R. Grace appealed, claiming that prior art about the product had never been published in a scientific journal. On 8 March 2005, that appeal was lost and the EPO revoked the Neem patent.[41]

Biotechnology

The biopesticide produced by extraction from the tree seeds contains limonoids. Currently, the extraction process has disadvantages such as contamination with fungi and heterogeneity in the content of limonoids due to genetic, climatic, and geographical variations.[42][43] To overcome these problems, production of limonoids from plant cell suspension and hairy root cultures in bioreactors has been studied,[44][45] including the development of a two-stage bioreactor process that enhances growth and production of limonoids with cell suspension cultures of A. indica.[46]

Claimed effectiveness against COVID-19

In March 2020, several claims were published on Facebook which included pictures of neem leaves and their use in treating or alleviating COVID-19 related symptoms such as fever, cough, sore throat, and shortness of breath.[47] These claims that neem leaves could be used as a treatment for COVID-19 circulated through Southeastern Asian countries such as Malaysia and India via social media. Malaysia’s Ministry of Health released an infographic titled “The usage of neem leaves for COVID-19 outbreak” in which they summarized the facts and myths related to the leaves being used to treat COVID-19. There is no clear evidence of the effectiveness of the leaves in treating infections, and only limited clinical studies have been conducted in determining their antimicrobial properties.[48]

Gallery

_in_Hyderabad_W_IMG_7006.jpg) Flowers

Flowers Unripe fruit

Unripe fruit Neem tree in a banana farm in India

Neem tree in a banana farm in India Neem tree farm

Neem tree farm- Twigs for sale

Fruit drying for oil extraction

Fruit drying for oil extraction Cleaning teeth by chewing stick

Cleaning teeth by chewing stick Native of Chhattisgarh with Neem branches and leaves for Hareli Festival

Native of Chhattisgarh with Neem branches and leaves for Hareli Festival A tree in Gambia

A tree in Gambia- A tree in Bangladesh

See also

- Azadirachtin

- Arid Forest Research Institute (AFRI)

- Neem cake

- Neem oil

- Babool (brand) of toothpaste

- Teeth cleaning twig (datun)

Further reading

- Ghorbanian, M; Razzaghi-Abyaneh M; Allameh A; Shams-Ghahfarokhi M; Qorbani M (January 2008). "Study on the effect of neem (Azadirachta indica A. juss) leaf extract on the growth of Aspergillus parasiticus and production of aflatoxin by it at different incubation times". Mycoses. 51 (1): 35–39. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0507.2007.01440.x. PMID 18076593.

- Razzaghi-Abyaneh, Mehdi; Allameh A.; Tiraihi T.; Shams-Ghahfarokhi M.; Ghorbanian M. (June 2005). "Morphological alterations in toxigenic Aspergillus parasiticus exposed to neem (Azadirachta indica) leaf and seed aqueous extracts". Mycopathologia. 159 (4): 565–570. doi:10.1007/s11046-005-4332-4. PMID 15983743. S2CID 1828729.

- Allameh, A; Razzaghi Abyane M; Shams M; Rezaee MB; Jaimand K (2002). "Effects of neem leaf extract on production of aflatoxins and activities of fatty acid synthetase, isocitrate dehydrogenase and glutathione S-transferase in Aspergillus parasiticus". Mycopathologia. 154 (2): 79–84. doi:10.1023/A:1015550323749. PMID 12086104. S2CID 19368341.

- "Neem officially becomes Sindh's tree". Daily Times. Karachi. 14 April 2010. Retrieved 15 July 2013.

References

- Barstow, M.; Deepu, S. (2018). "Neem". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T61793521A61793525. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-1.RLTS.T61793521A61793525.en.

- "Azadirachta indica". World Checklist of Selected Plant Families (WCSP). Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 14 December 2016 – via The Plant List.

- "Azadirachta indica". Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN). Agricultural Research Service (ARS), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- The Tree. National Academies Press (US). 1992.

- Compact Oxford English Dictionary (2013), Neem, page 679, Third Edition 2008 reprinted with corrections 2013, Oxford University Press.

- Henry Yule and A. C. Burnell (1996), Hobson-Jobson, Neem, page 622, The Anglo-Indian Dictionary, Wordsworth Reference. (This work was first published in 1886)

- Encarta World English Dictionary (1999), Neem, page 1210, St. Martin's Press, New York.

- Plant Risk Assessment, Neem Tree, Azadirachta indica (PDF). Biosecurity Queensland. 2008. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- Neem has been declared: what you need to know (PDF), Department of Land Resource Management, 2015, archived from the original (PDF) on 24 March 2015, retrieved 17 March 2015

- Neem Azadirachta indica (PDF), Department of Land Resource Management, 2015, archived from the original (PDF) on 24 March 2015, retrieved 17 March 2015

- Anna Horsbrugh Porter (17 April 2006). "Neem: India's tree of life". BBC News.

- "Neem Baigan". Jiva Ayruveda. Archived from the original on 9 July 2014.

- "ស្ដៅវ". Phyllyppo Tum.

- D.P. Agrawal (n.d.). "Medicinal properties of Neem: New Findings".

- S. Zillur Rahman and M. Shamim Jairajpuri. Neem in Unani Medicine. Neem Research and Development Society of Pesticide Science, India, New Delhi, February 1993, p. 208-219. Edited by N.S. Randhawa and B.S. Parmar. 2nd revised edition (chapter 21), 1996

- "Neem". Tamilnadu.com. 6 December 2012. Archived from the original on 11 April 2013.

- Neem, WebMD.

- M.V. Bhaskara; S.J. Pramoda; M.U. Jeevikaa; P.K. Chandana; G. Shetteppa (6 May 2010). "Letters: MR Imaging Findings of Neem Oil Poisoning". American Journal of Neuroradiology. 31 (7): E60–E61. doi:10.3174/ajnr.A2146. PMID 20448012.

- Material Fact Sheets – Neem Archived 12 February 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- YashRoy, R.C.; Gupta, P.K. (2000). "Neem-seed oil inhibits growth of termite surface-tunnels". Indian Journal of Toxicology. 7 (1): 49–50.

- Chaudhari, Ashok; Kulkarni, Ravindra; Mahulikar, Pramod; Sohn, Daewon; Gite, Vikas (2015). "Development of PU Coatings from Neem Oil Based Alkyds Prepared by the Monoglyceride Route". Journal of the American Oil Chemists' Society. 92 (5): 733–741. doi:10.1007/s11746-015-2642-3. S2CID 96641587.

- Nardi, Isabella (2007). The Theory of Citrasutras in Indian Painting. Routledge. p. 121. ISBN 978-1134165230.

- "Make A Neem Toothbrush (Neem Tree Home Remedies)". Discover Neem. Birgit Bradtke. Retrieved 16 July 2013.

- Bhambal, Ajay; Sonal Kothari; Sudhanshu Saxena; Manish Jain (September 2011). "Comparative effect of neemstick and toothbrush on plaque removal and gingival health – A clinical trial" (PDF). Journal of Advanced Oral Research. 2 (3): 51–56. ISSN 2229-4120. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 November 2013.

- Callahan, Christy (11 October 2010). "Uses of Neem Datun For Teeth". Livestrong.com. Demand Media. Retrieved 16 July 2013.

- Schroeder, Paul (1992). "Carbon storage potential of short rotation tropical tree plantations". Forest Ecology and Management. 50 (1–2): 31–41. doi:10.1016/0378-1127(92)90312-W.

- Puhan, Sukumar, et al. "Mahua (Madhuca indica) seed oil: a source of renewable energy in India." (2005).

- Heinrich W. Scherer; Konrad Mengel; Heinrich Dittmar; Manfred Drach; Ralf Vosskamp; Martin E. Trenkel; Reinhold Gutser; Günter Steffens; Vilmos Czikkely; Titus Niedermaier; Reinhardt Hähndel; Hans Prün; Karl-Heinz Ullrich; Hermann Mühlfeld; Wilfried Werner; Günter Kluge; Friedrich Kuhlmann; Hugo Steinhauser; Walter Brändlein; Karl-Friedrich Kummer (2007), "Fertilizers", Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry (7th ed.), Wiley, doi:10.1002/14356007.a10_323.pub2, ISBN 978-3527306732

- Bradtke, Birgit. "Neem Soap And Its Uses". Discover Neem. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

- Heuzé V., Tran G., Archimède H., Bastianelli D., Lebas F., 2015. Neem (Azadirachta indica). Feedipedia, a programme by INRA, CIRAD, AFZ (Association Française de Zootechnie) and FAO. Last updated on 2 October 2015

- Siddiqui, S. (1942). "A note on the isolation of three new bitter principles from the nim oil". Current Science. 11 (7): 278–279.

- Sidhu, OP, Kumar V, Behl HM (2004). "Variability in triterpenoids (nimbin and salanin) composition of neem among different provenances of India". Industrial Crops and Products. 19 (1): 69–75. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2003.07.002.

- "Union minister for Neem coated urea – Times of India".

- Delhi (9 January 2015). "Union Agriculture Minister emphasises about the potential of 'neem' coated urea". Business Standard India – via Business Standard.

- Krishnan, N; Swetansu Pattnaik; S. A. Deepak; Arun K. Hariharan; Prakhar Gaur; Rakshit Chaudhary; Prachi Jain; Srividya Vaidyanathan; P. G. Bharath Krishna; Binay Panda (25 December 2011). "De novo sequencing and assembly of Azadirachta indica fruit transcriptome" (PDF). Current Science. 101 (12): 1553–1561.

- Krishnan, N; Swetansu Pattnaik; Prachi Jain; Prakhar Gaur; Rakshit Choudhary; Srividya Vaidyanathan; Sa Deepak; Arun K Hariharan; PG Bharath Krishna; Jayalakshmi Nair; Linu Varghese; Naveen K Valivarthi; Kunal Dhas; Krishna Ramaswamy; Binay Panda (9 September 2012). "A Draft of the Genome and Four Transcriptomes of a Medicinal and Pesticidal Angiosperm Azadirachta indica". BMC Genomics. 13 (464): 464. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-13-464. PMC 3507787. PMID 22958331.

- Krishnan, N; Prachi Jain; Prachi Jain; Arun K Hariharan; Binay Panda (20 April 2016). "An Improved Genome Assembly of Azadirachta indica A. Juss". G3. 6 (7): 1835–1840. doi:10.1534/g3.116.030056. PMC 4938638. PMID 27172223.

- Narnoliya, L. K., Rajakani, R., Sangwan, N. S., Gupta, V., & Sangwan, R. S. (2014). Comparative transcripts profiling of fruit mesocarp and endocarp relevant to secondary metabolism by suppression subtractive hybridization in Azadirachta indica (neem). Molecular biology reports, 41(5), 3147–3162.

- Rajakani, R., Narnoliya, L., Sangwan, N. S., Sangwan, R. S., & Gupta, V. (2014). Subtractive transcriptomes of fruit and leaf reveal differential representation of transcripts in Azadirachta indica. Tree Genetics & Genomes, 10(5), 1331–1351.

- "Popularity of the name Nimai". babycenter.com. 2018. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- "India wins landmark patent battle". BBC News. 9 March 2005. Retrieved 2 October 2009.

- Sidhu, O. P.; Kumar, Vishal; Behl, Hari M. (15 January 2003). "Variability in Neem (Azadirachta indica) with Respect to Azadirachtin Content". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 51 (4): 910–915. doi:10.1021/jf025994m. PMID 12568548.

- Prakash, Gunjan; Bhojwani, Sant S.; Srivastava, Ashok K. (1 August 2002). "Production of azadirachtin from plant tissue culture: State of the art and future prospects". Biotechnology and Bioprocess Engineering. 7 (4): 185–193. doi:10.1007/BF02932968. ISSN 1226-8372. S2CID 85845199.

- Srivastava, Smita; Srivastava, Ashok K. (17 August 2013). "Production of the Biopesticide Azadirachtin by Hairy Root Cultivation of Azadirachta indica in Liquid-Phase Bioreactors". Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology. 171 (6): 1351–1361. doi:10.1007/s12010-013-0432-7. ISSN 0273-2289. PMID 23955295. S2CID 36781838.

- Prakash, Gunjan; Srivastava, Ashok K. (5 April 2008). "Production of Biopesticides in an in Situ Cell Retention Bioreactor". Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology. 151 (2–3): 307–318. doi:10.1007/s12010-008-8191-6. ISSN 0273-2289. PMID 18392561. S2CID 35506559.

- Vásquez-Rivera, Andrés; Chicaiza-Finley, Diego; Hoyos, Rodrigo A.; Orozco-Sánchez, Fernando (1 September 2015). "Production of Limonoids with Insect Antifeedant Activity in a Two-Stage Bioreactor Process with Cell Suspension Culture of Azadirachta indica". Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology. 177 (2): 334–345. doi:10.1007/s12010-015-1745-5. ISSN 1559-0291. PMID 26234433. S2CID 207357717.

- "No scientific evidence that neem leaves can 'cure' COVID-19 and its symptoms, doctors say". AFP Fact Check. 13 April 2020. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- "BERNAMA - No scientific evidence neem can cure COVID-19 infection - Experts". 8 April 2020. Archived from the original on 8 April 2020. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Azadirachta indica. |

External links

- Invasiveness information from Pacific Island Ecosystems at Risk (PIER)

- Neem information from the Hawaiian Ecosystems at Risk project (HEAR)

- Caldecott, Todd (2006). Ayurveda: The Divine Science of Life. Elsevier/Mosby. ISBN 978-0-7234-3410-8. Archived from the original on 29 December 2010. Retrieved 15 January 2011. Contains a detailed monograph on Azadirachta indica (Neem; Nimba) as well as a discussion of health benefits and usage in clinical practice.